1919 White Sox: The Pitching Depth Dilemma

This article was written by Jacob Pomrenke

This article was published in 1919 Chicago White Sox essays

Lefty Williams, left, and Eddie Cicotte carried the load for the Chicago White Sox in 1919. The two pitchers started, and won, more than half of the White Sox’s games during the regular season. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

As soon as Red Faber reported for spring training, Kid Gleason knew he had a big problem.

Entering the 1919 season, the Chicago White Sox’s first-year manager was counting on his workhorse aces Faber and Eddie Cicotte to lead his team back to the American League pennant they had won two years earlier. But Faber, the right-handed spitball specialist who had spent most of the 1918 season in the Navy during World War I, was weak from influenza and didn’t look well in his early throwing sessions at Mineral Wells, Texas, where the White Sox were getting in shape for the campaign.

The White Sox were returning almost their entire championship team from 1917. (The 1918 season had been cut short by the war as players were forced to comply with the US government’s “work or fight” order.) But some writers, like Baseball Magazine’s W.A. Phelon, predicted they would finish no better than fourth in the AL standings, primarily due to their lack of pitching depth.

The White Sox were returning almost their entire championship team from 1917. (The 1918 season had been cut short by the war as players were forced to comply with the US government’s “work or fight” order.) But some writers, like Baseball Magazine’s W.A. Phelon, predicted they would finish no better than fourth in the AL standings, primarily due to their lack of pitching depth.

Kid Gleason quickly grew tired of the criticism, but he never stopped worrying about his pitchers. The White Sox’s unreliable rotation proved to be a concern all season long and was a contributing factor in their World Series loss to the underdog Cincinnati Reds. In fact, some historians have argued that the White Sox might have lost to the pitching-rich Reds even if the Series had been played on the level.

Long before it became known that some White Sox players were intentionally throwing the Series, American League umpire Billy Evans was among the experts to cast doubt on Chicago as heavy favorites, writing in a syndicated column a day before Game One, “I am much in doubt as to Chicago’s chances. It is a pretty big task to ask two pitchers, Eddie Cicotte and Lefty Williams, to carry the burden of a nine-game series.”

Red Faber, the hero of the 1917 World Series and a future Hall of Famer, might have made the difference if he had been available. He tried for most of the year to assure Gleason that he was feeling fine, but the manager wasn’t fooled — and neither were American League hitters. Faber, weakened by illness and then hampered by arm and ankle injuries, started just 20 games in 1919 and compiled an 11-9 record with a 3.83 ERA, far above the league average of 3.22.

Red Faber, the hero of the 1917 World Series and a future Hall of Famer, might have made the difference if he had been available. He tried for most of the year to assure Gleason that he was feeling fine, but the manager wasn’t fooled — and neither were American League hitters. Faber, weakened by illness and then hampered by arm and ankle injuries, started just 20 games in 1919 and compiled an 11-9 record with a 3.83 ERA, far above the league average of 3.22.

Without Faber at full strength, the White Sox’s pitching staff was extraordinarily thin, even by Deadball Era standards when complete games were common and bullpen specialization was a concept that was decades into the future. Faber’s struggles forced Gleason to conduct an extensive (and mostly unsuccessful) search for other pitchers to provide support and much-needed rest for his two stars, Cicotte and Williams.

The 35-year-old Eddie Cicotte was the team’s undisputed ace, using his dazzling array of trick pitches — including the knuckleball, the emery ball, and his patented “shine ball” — to dominate AL hitters. He finished 29-7 with a 1.82 ERA and five shutouts in a league-leading 306⅔ innings pitched. Near the end of the season, with the White Sox safely in first place, he took two weeks off to rest his tired arm in preparation for an extended best-of-nine World Series against the Reds. This layoff in early September, which was widely reported in the newspapers, has long fueled speculation that White Sox management benched its star pitcher to spoil Cicotte’s chance at a 30th victory and deny him a promised $10,000 bonus. But there appears to be no truth to that story.

In any case, Cicotte did have a chance to win his 30th game and clinch the AL pennant, on September 24, but he faltered in the seventh inning and was pulled before the White Sox rallied to dramatically beat the St. Louis Browns, 6-5. Cicotte pronounced himself ready for the Reds after making a final tune-up start four days later, but questions still lingered about his health up until Game One of the World Series.

Claude “Lefty” Williams had shown flashes of stardom as the White Sox won it all in 1917, but in spite of his 17 victories, his inconsistency caused then-manager Pants Rowland to use him for just a single inning of that year’s World Series against the New York Giants. By 1919 Kid Gleason still wasn’t convinced the slightly-built southpaw with the peculiar side-arm delivery could hold his own as a full-time starter. But the 26-year-old Williams proved he was up to the task and followed Cicotte’s lead to go 23-11 with a 2.64 ERA and five shutouts in a team-high 41 games. Together, they combined for 52 of the White Sox’s 88 wins and almost half of the team’s 1,265⅔ innings pitched in the regular season.

To help take the load off Cicotte and Williams, manager Gleason and team owner Charles Comiskey made trades for other pitchers, called up minor leaguers and aging veterans, and even signed stars from the Chicago sandlots in the hopes that one or two of them might work out for the White Sox as a replacement for Red Faber.

Their biggest success story was a 25-year-old rookie named Dickey Kerr. The little left-hander, who stood just 5-feet-7, was a 20-game winner three times in the minor leagues before getting his chance in Chicago. In his first season with the White Sox, 1919, he went 13-7 with a 2.88 ERA in 39 games. But where he really shined was in his role as a bullpen ace, where he had a knack for holding opponents at bay as the White Sox’s explosive offense rallied for a victory in the late innings. Kid Gleason called on Kerr 22 times in relief and he went 7-1 with a 1.78 ERA in those appearances.

Their biggest success story was a 25-year-old rookie named Dickey Kerr. The little left-hander, who stood just 5-feet-7, was a 20-game winner three times in the minor leagues before getting his chance in Chicago. In his first season with the White Sox, 1919, he went 13-7 with a 2.88 ERA in 39 games. But where he really shined was in his role as a bullpen ace, where he had a knack for holding opponents at bay as the White Sox’s explosive offense rallied for a victory in the late innings. Kid Gleason called on Kerr 22 times in relief and he went 7-1 with a 1.78 ERA in those appearances.

In the World Series, Kerr’s strong performances gave Chicago fans hope after Cicotte and Williams were trounced by the Reds. His three-hit shutout in Game Three and a 10-inning victory in Game Six helped keep the White Sox’s chances alive. After Kerr’s second win, Gleason was so frustrated by his team’s uncharacteristic performance in the Series that he suggested he might start Kerr in every game the rest of the way. He didn’t follow through on the threat, and the White Sox lost the World Series, but Kerr was a lone bright spot in the franchise’s darkest hour.

Two other young pitchers who went on to greater acclaim but didn’t contribute much for the White Sox in 1919 were Charlie Robertson and Frank Shellenback. Robertson made his major-league debut on May 13 against the St. Louis Browns but was clearly overmatched by big-league hitters; he lasted just two innings before he was relieved by Kerr. The White Sox sent Robertson down to the minors for more seasoning and he wouldn’t return to Chicago for three more years. But in his fourth career start, on April 30, 1922, he threw a perfect game — just the fifth in major-league history — against Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers, a once-in-a-lifetime highlight in an otherwise mediocre career.

Shellenback, who possessed an outstanding spitball, had pitched decently for the White Sox as a 19-year-old rookie in 1918 and was expected to be a steady member of the rotation in 1919. But Shelly struggled to post a 1-3 record with a 5.14 ERA in eight games before he, too, was sent down to the minors in July. Those were his only career appearances in the major leagues; he never made it back because the National Commission banned his best pitch, the spitter, that offseason. Fortunately for him, he was allowed to continue throwing the wet one in the Pacific Coast League and he went on to enjoy a long, illustrious career with the Hollywood Stars, winning more than 300 games as one of the greatest minor-league pitchers ever.

The surprising thing about the White Sox’s lack of pitching depth is that just a few years earlier, they actually had the deepest pitching staff in the major leagues. Chicago had led the AL in team ERA in 1913, 1916, and 1917, and finished runner-up in 1914. But two of their former mound stars, Joe Benz and Reb Russell, each pitched in just a single game in 1919. Benz, known as “Butcher Boy” because he spent his offseasons working in the family shop, had risen to fame in 1914 after pitching a no-hitter against the Cleveland Naps and taking another no-hitter into the ninth inning two starts later against the Washington Senators. He was a steady pitcher with the White Sox for several years afterward, but age and injuries hampered his effectiveness. His final big-league appearance was a two-inning relief stint on May 2, 1919, and he was released two weeks later.

The Mississippi-born Ewell “Reb” Russell had one of baseball’s all-time best rookie seasons in 1913, winning 22 games and tossing eight shutouts. But he later suffered an elbow injury that left him unable to throw his curveball effectively, and he barely made the team out of spring training in 1919. In his only appearance, on June 13, he was yanked after two batters without recording an out. Russell was also given his release, and never pitched another game in the majors. But he resurfaced a few years later as an outfielder with the Pittsburgh Pirates, hitting .368 in 60 games as a platoon player in 1922.

None of them helped Kid Gleason solve his pitching dilemma, however. Cicotte and Williams helped lead the White Sox into first place on Opening Day and rarely looked back, but their manager kept looking for more pitching all season long.

In mid-May the White Sox acquired one of the fastest but wildest pitchers in the big leagues, Grover Lowdermilk, from the St. Louis Browns. On his sixth team in eight seasons — Chicago would be his last stop — Lowdermilk was given numerous chances to harness his talent. But the 6-foot-4 right-hander never overcame his lack of control. While he pitched well for the White Sox overall (5-5, 2.79 ERA in 20 games), Gleason didn’t feel comfortable using him down the stretch in tight games. Lowdermilk made just one start after August 31 and pitched one mop-up inning in Game One of the World Series.

John “Lefty” Sullivan was another talented fireballer with one glaring shortcoming who was given a tryout by the White Sox that summer. Plucked off the Chicago sandlots when Lowdermilk abruptly quit the team in mid-July (he returned two weeks later), Sullivan made a big name for himself as the strikeout king of the city’s semipro leagues. During World War I, while pitching for a military team based at Camp Grant, in Rockford, Illinois, he caught the White Sox’s attention when he outpitched Red Faber in a service game in front of a reported 12,000 fans. Sullivan was invited to spring training in 1919 but didn’t make the team, and then refused a minor-league assignment until the desperate Gleason called him back to make a surprise start against Walter Johnson and the Washington Senators on July 19. There was just one problem: Sullivan couldn’t field his position because of a lifelong heart condition that caused him to feel dizzy whenever he bent over to pick up a ball. Major-league hitters had trouble with Sullivan’s great stuff, but they could exploit his one weakness — and they bunted him right out of the league. He made just four appearances for the White Sox, finishing with an 0-1 career record and three errors in five fielding chances.

John “Lefty” Sullivan was another talented fireballer with one glaring shortcoming who was given a tryout by the White Sox that summer. Plucked off the Chicago sandlots when Lowdermilk abruptly quit the team in mid-July (he returned two weeks later), Sullivan made a big name for himself as the strikeout king of the city’s semipro leagues. During World War I, while pitching for a military team based at Camp Grant, in Rockford, Illinois, he caught the White Sox’s attention when he outpitched Red Faber in a service game in front of a reported 12,000 fans. Sullivan was invited to spring training in 1919 but didn’t make the team, and then refused a minor-league assignment until the desperate Gleason called him back to make a surprise start against Walter Johnson and the Washington Senators on July 19. There was just one problem: Sullivan couldn’t field his position because of a lifelong heart condition that caused him to feel dizzy whenever he bent over to pick up a ball. Major-league hitters had trouble with Sullivan’s great stuff, but they could exploit his one weakness — and they bunted him right out of the league. He made just four appearances for the White Sox, finishing with an 0-1 career record and three errors in five fielding chances.

As the summer rolled on and the first-place White Sox began to look ahead to the World Series, a handful of other pitchers, with varying degrees of talent and experience, tried to earn a spot in the postseason rotation: Win Noyes, Tom McGuire, Roy Wilkinson, Erskine Mayer, Dave Danforth, Big Bill James, and the superbly named Don Carlos Patrick Ragan. None were successful enough to warrant a start against the Reds.

Before the World Series began, prominent pundits like syndicated columnist Hugh Fullerton gave Cincinnati the edge on pitching strength and warned that the White Sox would be weakened if they had to rely solely on their two aces: “Critics … have been arguing that the Reds have a chance to beat the American Leaguers because of their superior pitching strength. … If Gleason gets away to a good start he will not force Cicotte or Williams to the limit of endurance, but will take a chance with others. But if the Reds get the jump on the Sox, Gleason has little choice but to fall back upon the two men who have won the championship for him.”

Cincinnati had five good starters — Dutch Ruether, Slim Sallee, Ray Fisher, Jimmy Ring, and Hod Eller — to Chicago’s two great ones, but they were plenty good enough to win the NL pennant by nine games over the New York Giants. The Reds’ 96-44 record was also eight games better than the White Sox’s at 88-52, although most observers agreed that the American League was the stronger circuit, having won eight of the previous nine World Series. The White Sox were heavy betting favorites entering the Series, but that all depended on Cicotte and Williams giving their best efforts. As Hugh Fullerton predicted, once they faltered in the first two games, Gleason had no one else but Dickey Kerr to fall back on.

Hall of Fame catcher Ray Schalk maintained for the rest of his life that if the White Sox had a healthy Red Faber for the 1919 World Series, they would have won it all even with eight of their teammates conspiring to hand it to the Reds. Back in 1917, Faber had appeared in four of the six World Series games against the Giants, winning three of them. There’s no telling how he would have fared against the Reds, but we can safely assume that he would have given the White Sox a better chance to win than the fixers Cicotte or Williams.

It’s also worth wondering how the White Sox might have fared if Gleason had been able to call on Joe Benz or Reb Russell or Frank Shellenback, too. The first two were proven winners (and Shelly would go on to win more pro games than anyone on the staff) who might have put a quicker stop to the bleeding after Cicotte was blasted out of the box in Game One and Williams lost his control in Game Two. Or Gleason might have chosen to start one of them in place of Cicotte on two days’ rest in Game Four or Williams in Game Five. (The tight World Series schedule, eight games played in nine days, also did the White Sox no favors.) Instead, the other pitchers Gleason did use — Roy Wilkinson, Grover Lowdermilk, Erskine Mayer, and Bill James — generally only made things worse when they took the mound. None of them were intentionally throwing games; the White Sox’s pitching just wasn’t all that strong outside of Cicotte and Williams.

Perhaps, then, we ought to give the Reds’ pitching staff a little more credit for winning the World Series. The White Sox batted only .224 in the World Series, and it wasn’t just the fixers who struggled. Leadoff man Nemo Leibold batted .056 (1-for-18) against Cincinnati pitching and future Hall of Famer Eddie Collins, who was considered one of the great “money” players in baseball by his contemporaries, hit .226 with just one RBI. Reds manager Pat Moran rotated his starting pitchers wisely, as he had been doing all season, and they responded well.

Kid Gleason didn’t have nearly as many good options, and he knew it. He spent all season trying to overcome his team’s one big weakness, and in the end it wasn’t enough. The White Sox just didn’t have enough pitching to beat the Reds.

JACOB POMRENKE is SABR’s Director of Editorial Content, chair of the Black Sox Scandal Research Committee, and editor of “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (2015).

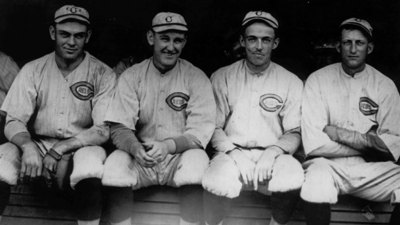

Cincinnati Reds pitchers held the White Sox to a .224 batting average during the 1919 World Series. Pictured from left: Hod Eller, Jimmy Ring, Dutch Ruether, Slim Sallee. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Sources

All statistics were found using Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org. Biographical information was found in the players’ SABR biographies and by accessing newspaper archives at ProQuest and Newspapers.com. In addition, the following articles were used as sources:

Evans, Billy. “Hard to Predict Winner of Series,” New York Times, September 30, 1919.

Fullerton, Hugh. “Cincinnati Shows Superiority With Leading Twirlers,” Atlanta Constitution, September 29, 1919.

Phelon, W.A. “Who Will Win the Big League Pennants?” Baseball Magazine, May 1919.