1951 Giants: At the Broadcast Summit

This article was written by Curt Smith

This article was published in 1951 New York Giants essays

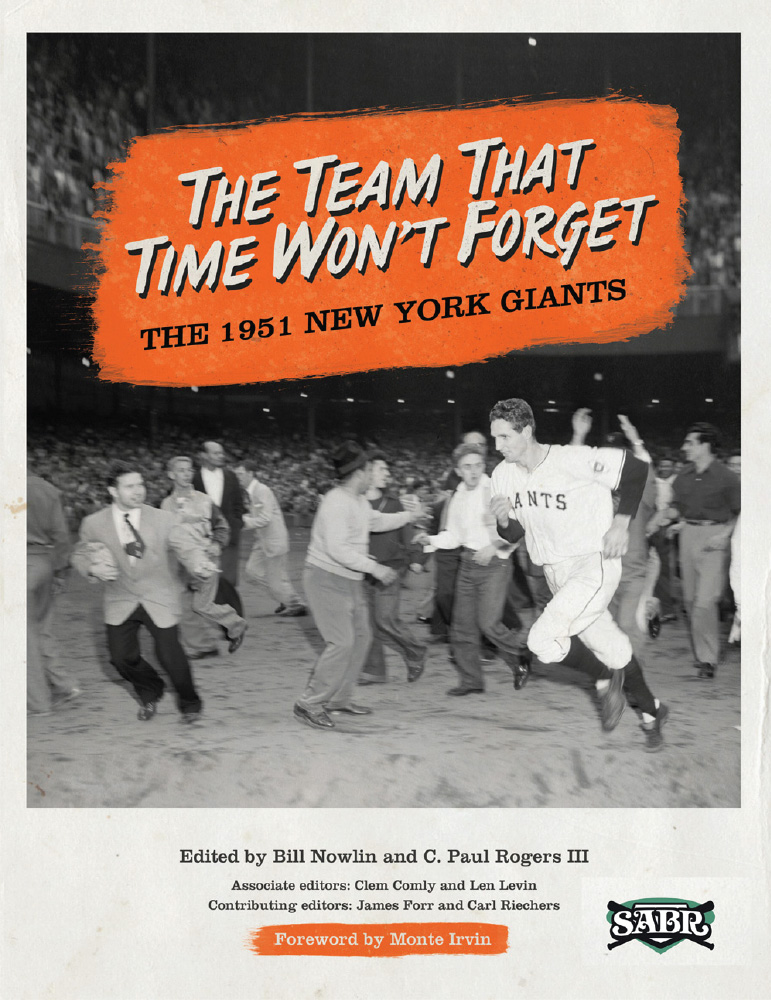

People of a certain age know where they were when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Franklin Roosevelt died, and Bobby Thomson swung. “The most famous sports moment of all time,” Jon Miller termed Thomson’s October 3, 1951, pennant-winning blast. We still recall the Shot Heard ’Round the World: Russ Hodges five times crying, “The Giants win the pennant!” Yet his artistry was only part of New York’s midcentury broadcast canvas. Never before, or since, have so many grand Voices of the Game etched baseball in one place, at one time, as the Big Apple in, say, 1951.

People of a certain age know where they were when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Franklin Roosevelt died, and Bobby Thomson swung. “The most famous sports moment of all time,” Jon Miller termed Thomson’s October 3, 1951, pennant-winning blast. We still recall the Shot Heard ’Round the World: Russ Hodges five times crying, “The Giants win the pennant!” Yet his artistry was only part of New York’s midcentury broadcast canvas. Never before, or since, have so many grand Voices of the Game etched baseball in one place, at one time, as the Big Apple in, say, 1951.

At Ebbets Field, the Cathedral of the Underdog, the Voice of the Dodgers made baseball on the air lyric and sweetly rural. Red Barber was a distant cousin of Southern writer Sidney Lanier. Hearing, you could tell. Colleague Connie Desmond had great command, fine diction, and a knockout future — until he flushed it down a flask. At 21, Vin Scully already made English a sudden magic place. The effect was to fuel a fanatical loyalty — our team, bub, and don’t you forget it. Brooklyn was “the only place,” said then-Giants Voice Ernie Harwell, “where people made a vocation of being a fan” — a borough against the world.

At the Big Ballpark in the Bronx, the Yankees, having won the 1949-50 World Series and about to win 1951-53’s, likely felt they owned the world. Surely their announcer was baseball’s most pre-eminent. Mel Allen had a voice that a florist must have decorated — to the newspaper Variety, “one of the world’s 25 most recognizable,” akin to Churchill’s or Sinatra’s. In 1951, Allen’s aide Curt Gowdy had just defected to the Red Sox. Dizzy Dean remained to say, “That hitter’s standing confidentially at the plate.” Mel dominated the booth, his “How about that!” a national idiom, as inexhaustible as the players who constituted baseball’s best team.

That left the Giants, often obscured by the Bums and Pinstripes, like their broadcasters were. The Georgian Harwell had left Brooklyn in 1950 for the Polo Grounds, having already swelled New York’s Dixie colony of Allen from Alabama and Barber and Dean of Mississippi’s pine and clay. The Jints’ Russ Hodges was the Jack Webb of big-league announcing, touting, “Just the facts, ma’am.” Wells Twombly wrote: “While Barber of the Dodgers gave his listeners corn-fed philosophy and humor and Allen of the Yankees told you more about baseball than you cared to know, Hodges of the Giants told it the way it was.”

If Allen played the Met, and Barber the Grand Ol’ Opry, Hodges, of rural Kentucky, pounded the piano at a roadhouse: “Total authenticity,” said Twombly. Once, working football, a tired Barber said, “Now for the second quarter, here is Russ Hughes.” Hodges, tongue-in-cheek, replied: “Thank you, Red Baker.” The Sporting News named Hodges 1950 Announcer of the Year. By any name, Hodges held his own against the nation’s two best-known sportscasters. Never has one site flaunted more baseball broadcast quality and quantity than 1951’s New York, New York.

If Allen played the Met, and Barber the Grand Ol’ Opry, Hodges, of rural Kentucky, pounded the piano at a roadhouse: “Total authenticity,” said Twombly. Once, working football, a tired Barber said, “Now for the second quarter, here is Russ Hughes.” Hodges, tongue-in-cheek, replied: “Thank you, Red Baker.” The Sporting News named Hodges 1950 Announcer of the Year. By any name, Hodges held his own against the nation’s two best-known sportscasters. Never has one site flaunted more baseball broadcast quality and quantity than 1951’s New York, New York.

Many preferred the Yankees’ Allen to even being at The Stadium, likely selling more cigars, cans of beer, and Americans on baseball than any announcer who ever lived. The age found him, like his team, at annual high tide. Mel had joined the Yanks in 1939, ultimately airing 18 pennants, 12 world titles, and nearly 4,000 games: to Sports Illustrated, “the most successful, best-known, highest-paid, most voluble figure in sportscasting, and one of the biggest names in broadcasting generally.” He covered 21 World Series, 24 All-Star Games, 14 Rose Bowls, CBS TV’s Mel Allen Sports Spot, NBC Radio’s Monitor, and nearly 3,000 Twentieth Century-Fox film newsreels — “This is your Movietone reporter,” seen and heard by up to 80 million weekly.

At one time or another Allen buoyed each US network: ABC, CBS, NBC’s Red and Blue, and the Mutual Broadcasting System. Said movie critic Jeffrey Lyons: “He could make the telephone directory sound like the Sermon on the Mount.” Once, in Omaha, Mel hailed a cab at night. In the dark, the cabby could not recognize him. He started driving, at which point Allen said simply, “Sheraton, please,” whereupon the car almost went off the road. Mel was a sponsor’s dream, home runs becoming a “Ballantine Blast” or “White Owl Wallop.” He was histrionic and touched by unpredictability. In 1950, Allen also got a day.

“The most unique tribute ever paid to a sportscaster sees a capacity crowd [actually 45,878] assembled at Yankee Stadium to honor baseball’s first Voice,” Fox chimed of the August 27 game. “Movietone’s own Mel Allen.” Former Postmaster General James Farley chaired. Gowdy emceed. Sixty-five gifts included a Cadillac, boat, TV set, and $9,000 in cash, used to start a Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth scholarship fund at Gehrig’s and Allen’s alma maters, Columbia and Alabama, respectively. A blonde unrolled a scroll: “Columbia Diamond Rings gift certificate presented to future Mrs. Mel Allen.” The policy went unredeemed, Allen never marrying. He prophesied futilely, as it occurred, about telling a grandchild about this day. “About all I’ll be able to say to him is, ‘How about that!’” Everywhere, Mel’s slogan branded hats, coats, and signs at Yankee Stadium.

That winter Gowdy was offered the Red Sox top radio/TV position. Improbably, he was torn. On one hand, he pined to be lead Voice. “I knew Mel would never leave, and the Sox meant Fenway, six states, great fans,” Curt said. On the other, he was “trying to make my name” in New York. Allen vowed to piggyback him to the Fens. Gowdy began there with two losses in the Bronx, Boston scoring once in 18 innings. Curt got telegrams blaming him for the bad Sox start. Worse, he mispronounced area towns with an English accent — Worcester, Swampscott, Ipswich.

Back at Fenway Park, Curt learned that Sox owner Tom Yawkey wished to see him. Terrified, he walked from the field up the stairs. Yawkey stood. “Curt, I just want to welcome you to the Red Sox. I followed you in New York and liked it.” Not a whiff of Swampscott: Expecting a sentence, Gowdy felt reborn. Yawkey even hired a speech tutor to help Curt pronounce confusing names.

In a cycle of irony, two future Red Sox announcers succeeded Gowdy in the Yankees booth. Bill Crowley aired the 1957-1960 Olde Towne Team. Art Gleeson did the Mutual Radio Game of the Day, then moved to Boston: “A gentleman, kind, courteous, never wed, loved baseball,” said Gowdy. Neither was mistaken for Dean, saying, among other things, that the batter swang, pitcher throwed, and runners were returning to their respectable bases. One week Ol’ Diz graced TV’s What’s My Line? “The guest could be Dizzy Dean,” blindfolded panelist Arlene Francis said. Dorothy Kilgallen: “Oh, no, this man is much too intelligent.”

In 1946 the Yankees had become the first club to have TV (DuMont; WPIX, Channel 11, by 1951) and 154-game home and away radio live (WINS, 1010 AM) coverage, ending road re-creations, which used Morse Code received in studio — “B1O” meaning ball one outside; “S2C” strike two called — to let an announcer re-create a game unseen. “You got better atmosphere live,” said Allen, “and got to know the players better away, lived with him, talked ball on the train.” Always Mel’s manner spoke of propriety and an elegance, not newly formed, that was neither bogus nor offensive. On air, John Mize became “a sentimental hero, in any case.” Phil Rizzuto was “an exponent of the [shortstop’s] art.” Cameramen on the roof drew an “uneven fringe of shadow.”

At home, their stadium was The Yankee Stadium. Bleachers trimmed the fence. The grandstand wrapped home plate beyond the bases. Steel girded the 71,699-seat Basilica. Roads led from New Haven, Rye, and Valley Stream to the Big Ballpark in the Bronx. The No. 4 subway train, on elevated tracks, eyed the field. Roman façade crowned the third tier. Distances from the plate would change, Allen laughed, when one plus one equaled three: 301 feet (to the left-field pole); 402 (left side, left-center bullpen gate); 457 (left-center); 407 (right-center); 344 (right side, right-center bullpen gate); and 296 (right). Center field was 461.

In July 1951 the Yanks’ Allie Reynolds threw a no-hitter. That September 28 he neared another vs. Boston in the first game of a double-header. “With two out in the ninth,” Mel retrieved that afternoon at The Stadium, “Ted Williams popped a foul. Catcher Yogi Berra dropped it. Unbelievably, Ted then fouled to the same spot. This time Yogi gets it — a no-hitter.” Former Yankees president Larry MacPhail likened the 5-foot-7, 190-pound Berra to “the bottom man on an unemployed acrobatic team.” Once he fielded a bunt and tagged the hitter and a runner coming home, later saying, “I just tagged everybody, including the ump.” Coach Bill Dickey helped the tyro: “He is learning me his experiences,” Berra smiled.

“Most seasons we made more money from Series cuts than we did our salary for the whole year,” said Rizzuto. Phil knew how to field, hit behind the runner, and bunt. On September 17, 1951, the Yanks hosted Cleveland, tied for the A.L. lead. The Indians’ Early Wynn, Bob Lemon, Mike Garcia, and Bob Feller ranked among the AL’s top five for most innings pitched. In the 1-all ninth, New York filled the bases. “Once again, Bob Lemon looks in, gets the sign. The three runners lead away. Here comes the pitch — and here comes Joe DiMaggio racing for the plate!” said Allen. “He [Rizzuto] lays it down toward the first-base line. Lemon races over, picks the ball up, has nowhere to throw it as Joe DiMaggio crosses the plate with the winning run as the Yankees win it, 2 to 1 — on a squeeze play!” The Bombers won their fourth pennant in the last five years.

Interest then turned to the “Senior Circuit” — actually, had centered there most of 1951. In his book The Boys of Summer, Roger Kahn wrote: “You may glory in a team triumphant, but you fall in love with a team in defeat.” By early 1951 the Brooklyn Dodgers were loved well beyond Flatbush USA. Since 1946 the Bums had lost: that year’s National League playoff, seven-game 1947 World Series, 1949 fall classic, and 1950 last-day pennant. In early 1951, few imagined that the Dodgers would top the topper, making the Bums the Hero of Every Dog That Was Under — beloved even now.

It may seem odd for a structural steel, reinforced-concrete park to become the personality of baseball in the flesh. At Ebbets Field it seemed as natural as a smile. The park became Green Acres, the urban place to be. Baseball was daily, letting a borough unite around a team. Brooklyn was needy: second-guessable and insecure. Above all, Ebbets was peewee: a participant, not spectator. Amazingly, Scully never saw it until “the [1950] day I went to work,” hired by Barber, Vin said. “Mom and pop didn’t own a car, never learning how to drive. Train, bus, and trolley seemed impractical. Brooklyn was so far away [from his Manhattan] home. We just never went,” missing Ebbets’s high and low walls, long and short distances, history and hyperbole: It mattered where you played.

A long out to Yankee Stadium’s left-center field — “Death Valley” — was a homer here. A 20-foot barrier at Ebbets tied left to center field, whose wall changed from 15 feet to 19 to 13 at a screen. Protruding five feet at a 45-degree angle, the concave wall wed center and right-field line. Its “lower 19 [bottom 9 sloped; top 10, rising vertically] were concrete,” wrote the New York Daily News’s Dick Young. “Above was another 19 feet of wire screen.” The scoreboard and wall had 29 different angles. The park was a calliope. Pinball was the effect. Scant turf compounded it: ultimately, left field, 343 feet from the plate: deep left-center at a bend of the wall, 395; center, 393; right-center, 403; right side of the right-field grandstand, 376; right-center scoreboard, 344 and 318 (left and right side, respectively); right, 297. The borough’s largest bar had 35,000 stools. As a child, Scully followed Brooklyn to see what it was up to. As seen by the boyhood Giants junkie, usually no good.

A 1998 film claimed There’s Something About Mary. Something about Brooklyn intrigued. Dodgers captain Pee Wee Reese wore No. 1 on his 1941-42 and 1946-57 uniforms. “You joked with people on a first-name basis,” he said. An Ebbets visitor heard players jabber, saw faces harden, felt pressure creep. Gladys Goodding — “one more d more than God” played the organ, serenading umpires with Three Blind Mice. Housewife Hilda Chester rang a cowbell in the stands. Behind first base, straw-hatted Jake the Butcher roared, “Late again!” of a pickoff. The Dodger Sym-Phony, a vaguely musical group, used a trumpet, trombone, snare and bass drum, and cymbals to snare a visitor. “Their specialty,” said Steve Jacobson, “was piping a strikeout victim back to his bench with a tune The Army Duff. [Because] the last beat was timed for the moment the player’s butt touched,” he might tardily sit down. “The Sym-Phony still had that last beat ready.”

On the Schaefer Beer scoreboard, one ad detailed the borough. Another hailed clothier and New York City Council President Abe Stark: “Hit Sign, Win Suit.” Most came by subway. Staying home, you heard a man born in 1908 before an age of cynicism, victimhood, or elbow-in-the-rib scatology. Ultimately, Barber won broadcasting’s Pulitzer, the George Foster Peabody Award, made six Halls of Fame, and did 33 years of play-by-play, constitutionally unable to utter a prejudicial word. Red was unafraid to dream — the son of a teacher and a locomotive engineer. In 1929, at 21, he hitchhiked to the University of Florida. One part-time job was reading a professor’s paper on campus radio. Barber had wanted to teach English. Finishing the paper, he was hooked on the wireless. Early Voices feigned that they were at the game live, not re-creating it. Not Red, putting the mike adjacent to the telegraph to amplify the dot-dash. “That Barber,” said a Brooklyn cabby. “He’s too fair.”

On the Schaefer Beer scoreboard, one ad detailed the borough. Another hailed clothier and New York City Council President Abe Stark: “Hit Sign, Win Suit.” Most came by subway. Staying home, you heard a man born in 1908 before an age of cynicism, victimhood, or elbow-in-the-rib scatology. Ultimately, Barber won broadcasting’s Pulitzer, the George Foster Peabody Award, made six Halls of Fame, and did 33 years of play-by-play, constitutionally unable to utter a prejudicial word. Red was unafraid to dream — the son of a teacher and a locomotive engineer. In 1929, at 21, he hitchhiked to the University of Florida. One part-time job was reading a professor’s paper on campus radio. Barber had wanted to teach English. Finishing the paper, he was hooked on the wireless. Early Voices feigned that they were at the game live, not re-creating it. Not Red, putting the mike adjacent to the telegraph to amplify the dot-dash. “That Barber,” said a Brooklyn cabby. “He’s too fair.”

Story studded Abraham Lincoln’s narrative. Franklin Roosevelt invented a piano teacher to illustrate a theme. Barber’s knew how anecdote fills baseball’s — indeed, public speaking’s — core. It flowed from reading Faulkner and Tennessee Williams and Eudora Welty — like Red, a Mississippian. The mound became a “pulpit.” You heard “tearin’ up the pea patch,” then Carlyle and Thoreau. A runner advanced on a “concomitant error”; the sky was “a beautiful robin-egg blue with … very few angels in the form of clouds”; there was “a rhubarb on the field.” Churchill called words “bullets that we use as ammunition,” using them to thwart tyranny. The Ol’ Redhead, Barber’s self-description, used them to regale.

Red was asked why New York’s baseball radio/TV colony was so Southern. “It’s how we grew up,” he said, fusing oral density and a gentle core. Harwell was more specific. “On the porch you’d hear about the local banker and grocer and who married whom.” Picture a Dodger hitting to left-center field. “Mentally, you saw it all at once,” said Ernie. “Runners, fielder chasing, relay throw, catcher bracing.” Radio was a sonata, falling lightly on the ear. TV was still life, deadened by statistic. Barber was “first to study players, take you behind the scene,” yet a worrywart. “You’d say something, and Red’d off-air glower, ‘Why would you say that?’ A tough taskmaster, not the warm guy on radio, so different”: a gulf widened by the borough’s heart.

“Red was the boss, and all he cared about was the betterment of the broadcast”: Tension high, Ernie said, “since Dodger fans were unbelievably loyal.” One day wife Lulu sat down in front of a fat man in a T-shirt. Reese led off the first. Standing up, the man shouted, “C’mon, you bum. Get a hit.”

Irked, Mrs. Harwell tapped the man on his shoulder. “I beg your pardon,” she said. “Do you know Mr. Reese?” The man replied, “No, lady, why?” She said, “If you did, I’m sure you’d find him a very nice gentleman.” The man replied, “OK, lady, I’ll lay off him if he’s a friend of yours.”

Billy Cox batted next. Flushed, the man stood: “Do somethin’, Cox! You’re a bum.” Again Lulu tapped him. “Lady,” he swiveled, “is this bum a friend of yours, too?”

Mrs. Harwell nodded. “What about the other bums on this team?” asked the man. “I know almost all the players,” she said. Muttering, he walked away.

“Lady, I’m moving. I came here to root my Bums to a win, and I ain’t gonna let you sit here behind me and spoil my whole afternoon.”

Harwell, who didn’t drink, was antipodal to Dodgers colleague Connie Desmond, who did. In 1943 the Toledo, Ohioan with the dreamboat voice joined Barber from the Yankees. Drinking then was more kosher than in our politically lockstep time. Postwar commuter trains rocked to gray flannel suits getting sloshed. Real men drank pals under the table. Desmond went a drink too far. He disappeared in September 1955, at which time Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley sacked him, after which next year Connie begged a final chance. Reluctantly, the Bums agreed. Reclimbing the wagon, hefell off again. Desmond never aired another major-league game. “He couldn’t handle it,” said Harwell, quietly, “which was too bad because he had it all. Stylish, he could be intoxicating.” Sadly, he was more often intoxicated.

Before his death in 2010, Harwell relived a happier end — his 1950 sally to the Polo Grounds. “Vinny took my place,” he said of Barber plucking Scully, 20, off the Fordham University campus, “which I consider my greatest contribution to baseball.” Like Red, the tyro tied realism, poetry, and voice less Pavarotti than Perry Como. Allen turned heads. Scully wooed them. He grew to love how in Flatbush he could almost reach out and touch the field. The booth — “small, jammed, but it’s what we knew” — hung suspended above boxes behind the plate. “It was open. No wire protected us” until a foul almost struck Barber’s face. “Balls came right back. We were so close, and also very aware of individuals.”

Once Hilda Chester bayed, “Vin Scully, I love you!” Flushed, Vin hung his head. “Look at me,” she ordered, “when I’m talking to you!” Even the P.A. announcer wrote shorthand chic. Tex Rickard sat near the home dugout, wore a sweater, and spun Texisms. “A little boy has been found lost.” Pitcher Preacher Roe left a game: “He don’t feel good.” Coats draped the left-field wall. Rickard asked: “Will the people along the railing in left field please remove their clothes?” For a time it seemed the 1951 Dodgers would finally remove postwar misery. That April Douglas MacArthur, recently axed by President Truman, saw his first game at Ebbets Field. He became a regular, seeing Brooklyn go 0-13. By contrast, the Dodgers, doing well with the General absent, swept a July series from the Giants. “We knocked ’em out,” said new Bums manager Charlie Dressen. “They’ll never bother us again.” Flatbush listened, but didn’t necessarily believe.

“This was a sports rivalry unlike any that ever was or probably ever will be,” Steve Jacobson wrote of Brooklyn-New York. “The fans rode the subway from their homes to the turf of the other team and cheered their raving hearts out. Each meeting was an angry collision. And sometimes it was close to hatred.” The Brooks and Jints played each other 22 games a year, radio/TV coursing through the city. “In Brooklyn, fans’d pelt the Giants with beer, coins, umbrella parts, whatever they could find,” said Scully, still living with his parents. “I’d go to the ballpark just hoping that no one would get hurt.” Urban myth says that the Brooks then began to choke. “People wrongly think we blew the pennant,” he said. “The Dodgers finished well enough [24-20], but it’s the playoff you recall” — facilitated by the Giants’ 37-7 finis. In late August the Dodgers still led the Giants by 13 games. A miracle followed — but why? The still-new musical South Pacific said it best: “Fools give you reasons. Wise men never try.”

Suddenly, the Apple’s baseball interest turned to, among other things, the Jints’ park and announcers. Across the Harlem River from Yankee Stadium stood the Polo Grounds, a two-tiered oasis in a hollow 115 feet below Coogan’s Bluff. Polo was never played there: After 1890, baseball was. Foul turf formed a vast semicircle behind the plate to each line. Roofed bullpen shacks anchored left-center and right-center field. Pee-wee foul lines earned the snarl “Polo Grounds home run.” Right field was 257 feet from the plate. A 21-foot upper deck overhang made left’s 279 feet seem closer. Center’s 483 feet seemed “binocular territory,” Sports Illustrated wrote. At 460 feet, stairs reached each team’s clubhouse. The rear wall read 505. “If the old-style parks meant personality,” said Herald Tribune writer Harold Rosenthal, “this park was the person of its time.”

Daily two people described the Giants over WMCA Radio, all games home and road, and WPIX TV, Channel 11, each game at the Polo Grounds, sponsored by Chesterfield cigarettes. Ultimately, Harwell had been or would be the first sports Voice baptized in the Jordan River, traded for a player, or to telecast coast-to-coast, as we shall see. He sang a duet with Pearl Bailey, had a racehorse named after him, and was sports editor of the Marine magazine Leatherneck. Oscar Wilde wrote The Importance of Being Earnest. The Wonder of Being Ernie wrote 80 song lyrics like “Move Over Babe, Here Comes Henry,” penned perhaps the greatest essay on baseball, The Game For All America, and aired 1948-2002 baseball, including the 1950-1953 Giants. How did he do this with such magnanimity and grace? In 1951 what Harwell did was pinch himself — and still not believe it.

His partner, Russ Hodges, then 41, was a gentle round teddy bear of a man: born in Dayton, Tennessee, his dad, a railroad telegrapher; like Allen moving almost every year; educated at the Universities of Kentucky and Cincinnati, passing the bar but never practicing. “In those days [1929],” Hodges said, “lawyers were jumping out of windows.” At 20, the bug-bitten barrister entered radio, soon requesting a raise. “Hodges,” the station manager said, “I can go down any alley, fire a shotgun, and hit 30 guys who are better than you.” Unfazed, Russ aired the Reds, Cubs, and White Sox, using re-recreations and sound effects — a pencil hitting wood mimed bat hitting ball — to mask being in studio and not at the game.

In 1942 Hodges joined the Senators. In 1946 Allen, needing a No. 2 and “knowing of Russ’s law degree,” hired him, said Mel, a lawyer. “Soon Russ and I almost read each other’s mind.” As noted, Opening Day launched TV and live 154-game radio. “We had one staff, not today’s three [cable/free TV/radio],” said Allen. “Russ and I’d pass each other on a ladder, do several TV innings, then breathe.” Equally fine were the counselors, completing each other’s thoughts. Their ad agency began two-way voice ads. “At inning’s end I’d ask something. When next inning started, Russ’d answer. Love those spontaneous ad-libs.” Once Mel changed a question, Hodges giving a scripted answer, “which made no sense, which was the idea,” Allen said. “Russ got tickled and ran out of the booth. The agency didn’t know what to do with us.” Wisely, it did nothing.

One day Yankees head Larry MacPhail summoned Hodges. “Tell Allen no more ad-libbing.” Ex-Marine Russ saluted: “Yes, sir. And now may I have the script for the rest of the game?” Inevitably, puns revived. A British umpire wouldn’t work night games “because the sun never sets on the British umpire,” said Mel. Finally, Russ said, “You just go on and fracture the audience. I’m going out for a breath of fresh air.” Off air, Hodges found his roommate less Oscar Madison than Felix Unger. Allen ate at odd hours, put pajamas on at 10 p.m., and could be “a bundle of nerves,” said Russ, less intense. Snuffy Stirnweiss once popped up a 3-1 ninth-inning pitch, stranding the tying run. At 4:30 a.m., Russ awoke to groans in the next bed. “Mel, should I get a doctor? What’s the matter?” he said. “I just can’t forget about that 3-and-1 pitch to Stirnweiss,” Allen said. “Don’t you think he made a mistake swinging?”

Until his 1996 death, Allen dubbed Hodges “my favorite partner. No ego, great to work with, accurate, knew the game.” In 1949 Russ was named the Giants’ Voice, replacing Frankie Frisch. Less lyric than Harwell, Russ seemed more blue-collar, saying, “I’m rather unimaginative. I don’t believe in keeping the listener on the edge of their seats.” Hodges contacted Bell’s palsy, paralyzing a side of his face. Recovering, he did NBC college football, the Kentucky Derby, and many crucial network boxing fights. Hodges won the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Ford C. Frick award for broadcast excellence, like most of New York’s 1951 colony: Allen, Harwell, Barber, Scully, and Gowdy — a nonpareil feat. Russ, his election posthumous, would have demurred. “I know darned well I don’t have a good radio voice.” On the other hand, “I know sports well” — well enough to make a rock of ages call. On May 25, 1951, the Giants, under .500 and 4½ games behind Brooklyn, received a future rock of a franchise when Willie Mays reported after batting .477 at Triple-A Minneapolis. Mays went hitless his first 12 major-league at-bats. “What’s wrong, son?” said New York manager Leo Durocher, who found him crying. “Mister Leo, it’s too far for me, I can’t play here,” Mays, 20, said. “Willie, I brought you here to do one thing — play center field,” said Durocher. “And as long as that uniform says ‘New York Giants’ and I’m the manager, you will be in center field every day.” He was.

By September 20 the Giants had cut the Dodgers’ lead by nine games in five weeks. Even so, New York trailed by six games in the loss column with seven left overall. The Giants swept a three-game series with Boston while Brooklyn lost two of three to Philadelphia: margin 2½. The Jints then beat the Phils while the Bums dropped a twin bill to Boston. On Friday, September 28, the pursuer nabbed the pursued: each team 94-58. Both won Saturday, the Giants’ Sal Maglie and Dodgers’ Don Newcombe blanking the opposition. Next afternoon New York took Sunday’s regular-season finale, edging Boston, 3-2, then rode back to New York by train. As Hodges wrote in his 1963 memoir, My Giants, he used the train telephone to call the team office, monitoring Brooklyn’s game in Philadelphia.

The Dodgers fell behind, 6-1. Desperate, they rallied to trail, 8-5, before scoring three eighth-inning runs. In the noisy train, Russ, developing a cold, had to shout to relay play-by-play to players. Finally — the Bums had this thing about the final day — Robinson made “an incredible diving 12th-inning catch,” said Hodges, “hurt his elbow but stayed in and homered in the 14th to win [9-8].” A day later the best-of-three NL playoff series began: “A world,’ said Russ, “focused on our rivalry.” Even the Voice of the Yankees was transfixed. “Think of it,” said Allen. “Three New York teams out of the big leagues’ 16 remain. One’s already in the Series [his], the other two tied.” If ever “How about that!” applied, it did to 1951’s postseason.

In 1947 Americans had owned just 17,000 television sets vs. 58 million radio receivers, “each medium fearing the other,” said Allen. By 1951 TV had become an irresistible object, totaling 10 million sets and nearly 10,000 sold each day. It had momentum. Radio was still an immovable object, many dubbing the kinetic tube a passing trend. It had cachet. The Dodgers-Giants playoff became the then-most widely covered event in each medium’s history. Good friends Hodges and Harwell split the series between Jints flagship WMCA and TV’s first network coast-to-coast sports telecast — Game Three on CBS. “We’d tossed a coin, and ole’ Russ was going to be stuck on the radio,” Ernie laughed. “So I was feeling a little sorry for Hodges. There were five radio broadcasts [Mutual, Liberty, Giants, Dodgers, and re-created Brooklyn Dodgers Network] and I was gonna be on TV, and I thought that I had the plum assignment.” The plum soon soured.

The best-of-three opus began at Ebbets Field, New York’s Jim Hearn beating Ralph Branca, 3-1. Bobby Thomson, who will revisit our narrative, went yard off the loser. Monte Irvin also homered, as did Brooklyn’s Andy Pafko. Each run scored by going deep. Next day changed place (Coogan’s Bluff) and score (Bums, 10-0, behind Clem Labine. Four Dodgers homered: Pafko, Jackie Robinson, Rube Walker, and another Hodges, Gil). That night Russ Hodges stayed awake gargling. Worse, “to test my voice, I kept talking into an imaginary microphone at home,” which hurt Russ’s throat. “I had trouble breathing, my nose was running, and I was sure I had a fever. Later Brooklyn P.A. voice Tex Rickard rued how Game Three wasn’t in Flatbush, saying. “I’d have introduced Thomson against Branca.” Instead, the Flying Scotsman introduced himself.

October 3, 1951, 3:58 P.M. A then-schoolboy still knows the script. The Jints are behind, 4-2, in the bottom of the ninth inning. Thomson awaits the Brooklyn reliever’s two-on, one-out pitch. “Branca throws. There’s a long drive!” Hodges bayed on WMCA. “It’s going to be, I believe! … The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! Bobby Thomson hits into the lower deck of the left-field stands! The Giants win the pennant! And they’re going crazy! They are going crazy! Oh-oh!”

Confetti swirled. Infielder Eddie Stanky wrestled Durocher to the ground. Brooklyn staggered to its clubhouse. A picture by 1937-57 Dodgers photographer Barney Stein showed Branca, on his stool, shattered. “Everybody remembers it now,” said Thomson. “But you have to understand the feeling between those teams. I didn’t think of the pennant — only that we beat the Dodgers.” Hodges ate noise thick enough to chew. “I don’t believe it!” Russ yelped. “I do not believe it! Bobby Thomson hit a line drive into the lower deck of the left-field stands, and the whole place is going crazy! The Giants — [owner] Horace Stoneham is now a winner — the Giants won it by a score of 5 to 4, and they’re picking Bobby Thomson up and carrying him off the field!”

Before videotape, a film camera had to tape a TV screen or monitor to record, a process called kinescope. “Kinescopes were fuzzy and extremely bulky,” said Harwell. “So the networks of the 1950s saved almost nothing.” Few even had a radio reel-to-reel recorder: “hard to carry around, so the average guy didn’t have one.” In Brooklyn, restaurant waiter Laurence Goldberg did. Legend dubs him a Dodgers fan, wanting to preserve their victory. In fact, Goldberg liked the Giants. Having to leave for work, he had his mother hit the “record” button in the bottom of the ninth. Ultimately, Russ sent Goldberg $10 to use his borrowed copy to record a Christmas gift for friends. That fall sponsor Chesterfield cigarettes released a record of “the most exciting moment in baseball history”: Russ, calling Thomson’s blast. It also put the lie to revisionists’ barbs.

One writer said Hodges stood on his chair for two minutes screaming “The Giants win the pennant!” Barber dubbed Russ “unprofessional,” to which Hodges’ 1958-1970 partner Lon Simmons said, “He was dramatic, but gave the essentials: score, meaning, who won.” Irrefutably, the call made Hodges Cooperstown Class of 1980. Harwell, honored by the Hall in 1981, would also never forget 1951. “It’s gone!” he said immediately of the drive, then stopped. Brooklyn’s Pafko seemed glued to the left-field wall. “Uh, oh,” Ernie thought, “suppose he catches it.” Back home, Harwell remained dazed. “I’ve seen that look on your face twice in my life,” said wife Lulu. “When our first child was born and the day we got married.” We trust her, since 1951 TV did not preserve his call. “What did I get? Anonymity. What did Russ get from his radio call? Immortality!” Ernie joked. “To this day only Mrs. Harwell and I know that I did maybe the most famous call of all time.”

Thomson’s homer still means Hodges’ call. Yet other Voices described it, too. In 1947 Cookie Lagagetto’s ninth-inning single had wrecked Bill Bevens’ bid for the World Series’ first no-hitter. Barber’s depiction had been electric, ending with “Well, I’ll be a suck-egg mule.” Red said of Thomson’s belt: “Branca pumps, delivers. A curve ball, belted deep out to left field! It is — a home run! And the New York Giants win the National League pennant. And the Polo Grounds goes wild!” Scully was always glad Barber called the blast on the Bums’ WMGM flagship. “Then [he was 23] it would have been too much for me.” Other photographs and memories turn Vin to October 3 the way a heliotrope turns toward the sun.

“When they were going to the bottom of the ninth inning, and the Dodgers were leading,” Scully mused, “I saw a man walking in the lower deck of the Polo Grounds carrying this great big horseshoe of flowers that you might see at a funeral home.” A banner cloaked the horseshoe:

“GIANTS, REST IN PEACE.” Vin “always wondered, after the home run, what did that guy do with those flowers? You can’t hide that. You can’t just suddenly put that under your coat.”

Another flashback referenced the clubhouses. “[They were] located side-by-side, back of center field, and while we could hear the Giants whooping it up at their victory celebration, in ours it was like a morgue,” said Scully. In shock, Reese and Robinson lay on the rubbing table. Finally, Pee Wee raised his head, saying, “You know what I really don’t understand?” Jackie: “What?” Reese: “How after all these years playing baseball I haven’t gone insane.”

As Harwell said, the NL playoff then had no radio/TV exclusivity. If you wanted to broadcast, you could. This let a second Dodgers network air Thomson’s poke. In 1951 O’Malley asked general manager Buzzie Bavasi to find a Voice (like Red, someone antebellum) and plan (Brooklyn Dodgers Radio Network) to serve an area then beyond local big-league coverage. By 1952 Virginian Nat Allbright addressed a baseball-high 117 outlets from Cleveland to Miami. “People didn’t know we re-created,” he said. Mail sent to “Nat Allbright, Brooklyn Dodgers, Ebbets Field” was forwarded to his Virginia home. A listener fancied Nat and Red, cozying in Flatbush. Allbright imagined Don Newcombe’s fastball from a D.C. studio. “I’d say, ‘Sweat’s dripping down Big Newk’s face.’ ” Like Barber, he was personal. “Pirates crowds stunk, so I’d cut noise. For Milwaukee, we’d tape polka music.” Nat’s first game was The Shot — “O’Malley’s dress rehearsal for ’52.” He aired his final of circa 1,500 Dodgers games in 1962, long after they decamped for California.

Two other networks also broadcast Thomson’s touché. Each day but Sunday Mutual aired a Game of the Day to 700 outlets, its lead Voice Al Helfer, who “drank triples without any apparent effect,” wrote Ron Bergman, “and sometimes wore a cashmere cardigan that cost the lives of a herd of goats.” The 1940-41 Dodgers announcer rejoined them in 1956-57. In 1950-54, though, Al boarded a plane six days a week for Boston, Brooklyn, or Chicago, among big-league cities, to air his favorite sport live. Helfer did the entire 1951 playoff, as did another pioneer, Gordon McLendon, founder and Voice of Liberty Broadcasting, which boasted as many as 431 outlets, most in the hinterlands, hanging on his re-creations. The Old Scotchman— McLendon had only turned 30 that June— aired the last month of the Giants-Dodgers joust. “From the bay of Tokyo, to the tip of Land’s End, this is the day,” he began the October 3 finale. Thomson’s wallop bred “The Giants win the pennant!” Silence. Crowd noise. Finally, Gordon bellowed: “Well, I’ll be the son of a mule.”

Bob Costas was born March 22, 1952. Decades later, the broadcaster listened to the tape. “McLendon’s roaring from the first pitch — no letup. All the stops are out. The end of the world.” For nearly two months the Giants had played like extraterrestrials. Could they continue? A nation stopped to find out. Allen, Hodges, and Jim Britt moored NBC-TV’s World Series coverage over 64 stations, including one in Mexico. Helfer boomed his baritone over Mutual, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and Armed Forces Radio. Dave Koslo, the Giants’ only available starter, threw their Series opener, a seven-hit complete game victory over the Yankees’ Allie Reynolds, aided by Monte Irvin’s steal of home and Alvin Dark’s three-run homer: 5-1. Next day the Bombers’ Eddie Lopat slowballed the Jints, 3-1, to even the Series, Joe Collins homering and Larry Jansen losing. In Game Three, five unearned runs gave the Giants a 6-2 victory and 2-1 game lead. Rain then postponed Game Four, giving Reynolds a needed day of rest.

“We had ‘em,” Hodges huffed, “till Game Four was called.” The delay let Reynolds pitch on three, not two, days’ rest: He beat the Jints, 6-2. Next day pinstriped hits rattled around the Giants oblong home: 13-1. Back across the Harlem River, the Yankees led Game Six, 4-1, entering the ninth inning. The Giants then scored twice, prompting the same thought in millions of minds — “Will it happen again?” Pinch-hitter Sal Yvars lined to right field, where Hank Bauer made a sliding catch, Allen crying, “Three straight for The Perfessor!” — Casey Stengel.

Of all the baseball Voices of New York’s 1951, only Vin Scully is still alive, not letting us wander far from baseball, still inviting us to “pull up a chair.” The others are gone, having made us feel the sunlight, dust, and heat; fielder crouched, batter cocked, and pitcher draped against the seats — above all, that there was no place on earth that you would rather be. Mel and Russ. Red, Curt, and Ernie. Vin, Connie, and Ol’ Diz. Al Helfer and Gordon McLendon on network. Perhaps baseball never meant more to America than it did in the mid-20th century. Perhaps its broadcast ministry was never more riveting and self-evident than in the City of New York.

“Here lies the summit,” British statesman Edmund Burke once said of a colleague. “He may live long. He may do much. But he can never exceed what he does this day.” To New York’s 1951 baseball public, each day was the summit in a glorious place — and time.

CURT SMITH “is the voice of authority on baseball broadcasting,” says USA Today. His 16 books include the classic Voices of the Game; Storied Stadiums; The Voice: Mel Allen’s Untold Story; A Talk in the Park; Pull Up a Chair: The Vin Scully Story; The Storytellers; Our House; and George H.W. Bush: Character at the Core. Smith is a GateHouse Media columnist, Associated Press award-winning radio commentator, and senior lecturer of English at the University of Rochester. He also has hosted Smithsonian Institution, SiriusXM Radio, and National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum series, written ESPN TV’s “Voices of the Game” documentary series, and written more speeches than anyone for former President George H. W. Bush. The New York Times terms his work “the high point of Bush familial eloquence.” Smith lives with his wife and two children in Upstate New York.

Sources

The vast majority of this article’s material, including quotes, is derived from the books Voices of The Game: The Acclaimed Chronicle of Baseball Radio & Television Broadcasting — from 1921 to the Present (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992); Storied Stadiums: Baseball’s History Through Its Ballparks (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2001); Voices of Summer (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2005); The Voice: Mel Allen’s Untold Story (Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2007); Pull Up a Chair: The Vin Scully Story (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2009); A Talk in the Park: Nine Tales of Baseball Tales from the Broadcast Booth (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2010); and Mercy! A Celebration of Fenway Park’s Centennial Told Through Red Sox Radio and TV (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2012.) by Curt Smith. Material, on Russ Hodges’ October 3, 1951, illness and Lawrence Goldberg’s role in preserving Bobby Thomson’s homer is in Tim Wiles’ “A Paper Trail to History,” in the Hall of Fame’s Opening Day 2011 Memories and Dreams issue.