Catcher ERA — Once More with Feeling: It’s Tough to Be a Rookie

This article was written by Tom Hanrahan

This article was published in Summer 2009 Baseball Research Journal

Do catchers in general do a better job of handling the pitching staff as they gain major- league experience? In a previous study published in By the Numbers (“Catchers—Better as Veterans,” spring 2000), I concluded that the answer to this question was a resounding Yes! The two sets of data used were the team ERA (adjusted for league average) of all clubs where the same primary catcher was used in consecutive seasons, from 1946 through 1987, and the number of previous major-league games the catcher had caught prior to each year.

In this study, I found that the team ERA dropped significantly as a catcher went from being a rookie to having spent four to seven years with the same club. The effect was particularly strong when dealing with rookie catchers with very little experience (fewer than 50 MLB games caught). Virtually every team (16 of 17) that kept these catchers had a better ERA by the time they gained more experience.

Some students of the game pointed out a potential flaw in my methodology. I attempted to “hold all other things equal” by comparing catchers in rookie seasons to their later years while with the same team, assuming that changes in the pitching staffs, while not inconsequential, would be random enough. However, it is possible that teams employing a rookie catcher might be in a “rebuilding” year more often than is typical, and thus employing an untried or subpar pitching staff at the same time.

To make a quick check of this, I recorded team records for the year before a rookie catcher’s being used. These teams (for the rookie catcher in the database) averaged only about 76 wins (per 162), which does suggest a tendency to rebuild when a rookie catcher is brought in. The team records of the catchers’ rookie years wouldn’t appear to be of much analytical value, since that would be influenced by the catcher (or so the theory goes). Well, now what? I decided what I needed to do was to compare specifically pitcher–catcher pairs on the same team as the catcher matured. This ought to show any influence the catcher has on the pitcher over time. And that is the subject of this article.

THE UPDATE

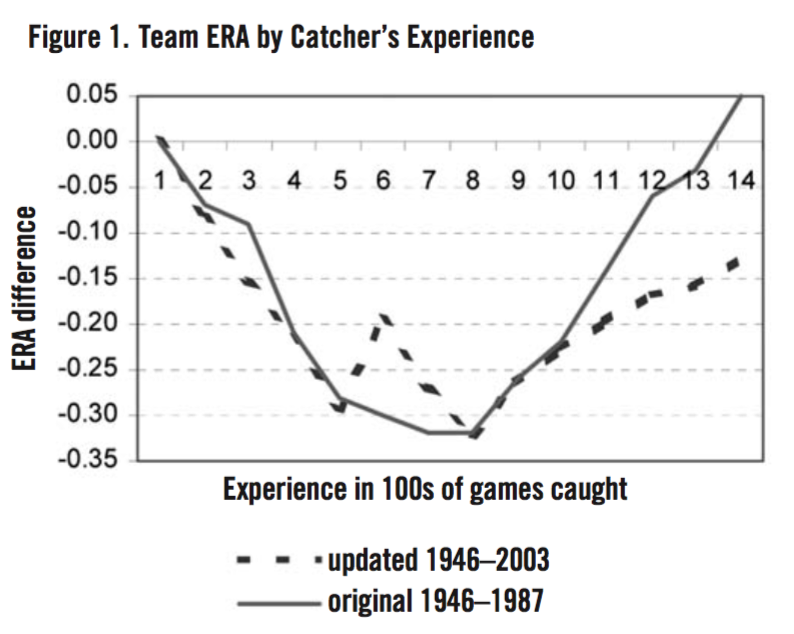

First, I updated my original study. Actually, a gentleman named Jerry Swenson did all of the research (read: grunt work) for me. The database now includes the years 1988 through 2003, adding 47 percent more players to the file, increasing the number of catcher-years from 560 to 835. The additional years used did not change the original conclusions: Team ERA improved significantly from the catchers’ rookie seasons to their prime years. Figure 1 shows two curves, the original and the new (combined) relative change in team ERA versus how many games a catcher had spent with a team. The one noticeable difference found when adding the more recent data is a lessening of the poorer ERAs when a catcher was well past his prime (> 1,000 games caught). However, there isn’t as much data in this area (many catchers are not playing full-time by this point), so it could be just random noise.

Figure 1. Team ERA by Catcher’s Experience

PITCHER–CATCHER PAIRS: THE DATA

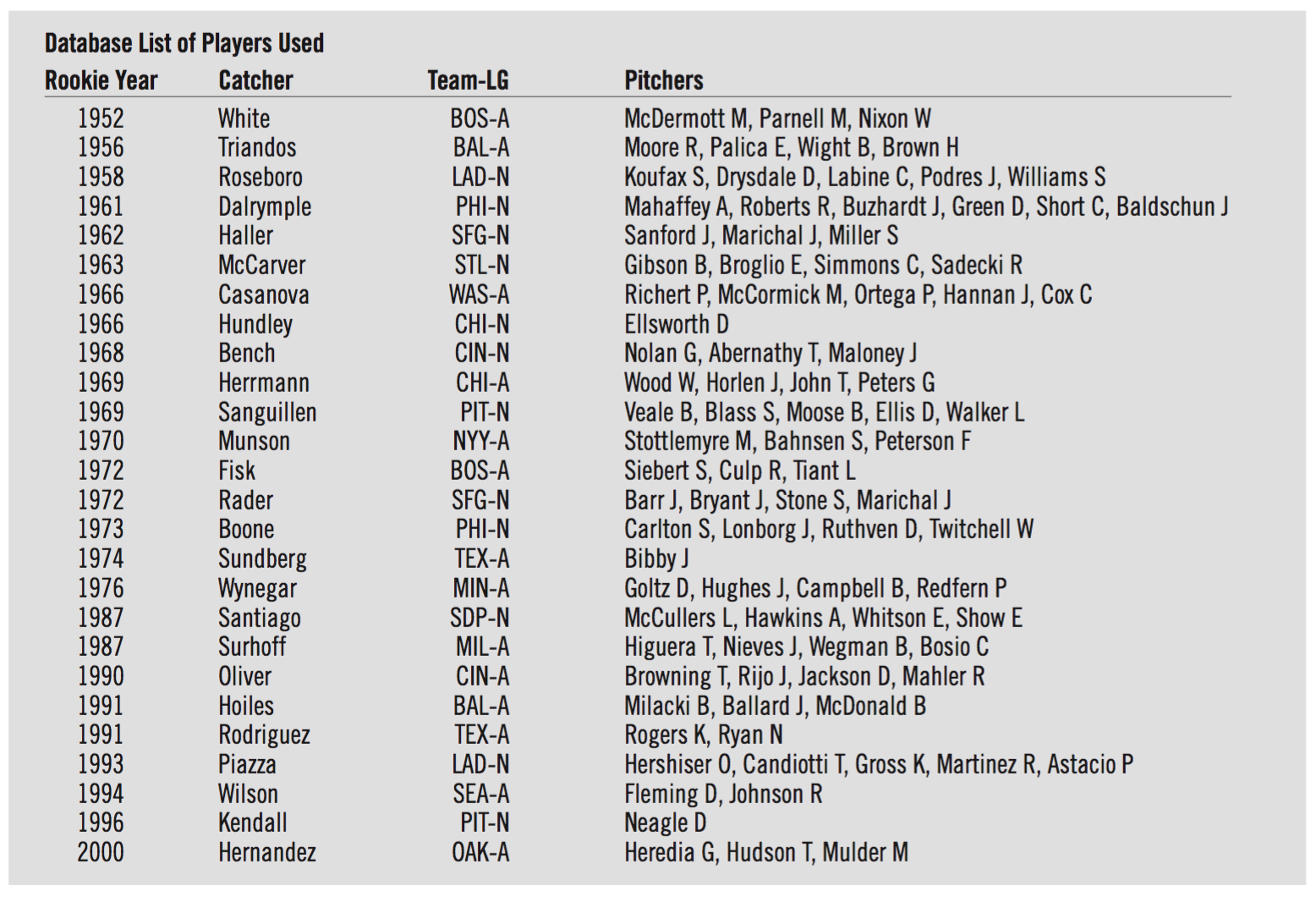

In the original study, I identified 16 catchers who, after having caught fewer than 50 games in the major leagues, had a full-time rookie year and then stayed with a team through their prime years. This was a set of catchers who burst on the scene and were good enough to continue playing. From Jerry Swenson’s research of recent years, this set of catchers now numbers 26.

I found all of the pitchers who tossed at least 100 innings in these catchers’ rookie seasons. I then looked for any other seasons where the same pitcher threw at least 100 innings in a year when the catcher was in his prime with the team. I defined “prime” largely by the findings in the previous study, as when the catcher had four to seven years with the team. I could then compare the individual pitchers’ ERA in different years, all with the same catcher. I also entered data for all of the pitchers who threw at least 100 innings in the year prior to the catcher’s rookie season (when they were obviously throwing to a different receiver). All of these data were entered into a file that contains 26 catchers, 90 catcher–pitcher pairs, and a total of 233 paired seasons. A list of names, teams, and years appears at the end of this article. Of course, there are many more cases of pitchers throwing to rookie or veteran catchers—but, again, this data is only for those pitcher–catcher pairs who played for the same teams.

FROM ROOKIE TO PRIME BACKSTOPS

First, I will compare the seasons when the catchers were raw rookies to their time as veterans of four to seven years’ service.

Example: In 2000, Ramon Hernandez had his first full year in MLB, catching 142 games for the Oakland A’s. He had caught only 40 games previously. In 2000, there were five pitchers who threw at least 100 innings for the A’s. Only two of these also threw 100 innings in 2003 (and 2004—while our research stopped initially at 2003, I since updated any numbers with data from the 2004 campaign), which would be “rookie year plus 3 (and plus 4)”: Mark Mulder and Tim Hudson. Hud- son’s ERA in 2000 was 4.14, and in 2003–4 combined it was 3.07. Mulder put up a 5.44 ERA in 2000 and a 3.84 ERA in 2003–4. So, Hudson and Mulder were both more effective when Hernandez was a veteran receiver with the A’s.

Overall results:

- There were 39 qualifying pitcher–catcher Of these, 22 have lower ERAs with the veteran catcher.

- Pitchers throwing to the catchers as veterans had a composite ERA that was 0.40 lower than when the catchers were rookies.

- Assuming a normal distribution, this 40 difference is well beyond the bounds of chance (greater than 2 sigma).

There was a significant amount of variation in the data. A few points stand out. In 1961, after a decent first season in the bigs, Chris Short put up a disastrous 5.94 ERA for the Phillies in Clay Dalrymple’s initial season as Philadelphia’s primary catcher. Short would later post ERAs consistently in the 2s with Dalrymple in 1964 through 1967. Another large jump was exhibited by Sandy Koufax, who in 1958 managed only a 4.48 ERA throwing to a young Johnny Roseboro. Of course, a few years later, Roseboro was privileged to catch numerous gems from Sandy’s amazing arm; certainly the move to Dodger Stadium helped as well. Conversely, the largest increase in ERA from rookie to veteran catcher was the combo of Luis Tiant and Carlton Fisk. Luis put up a brilliant 1.91 ERA in Fisk’s rookie year (1972) but was much less effective in the later 1970s.

One problem area I saw is that Steve Carlton was famous for having his own personal catcher (Tim McCarver) late in his career with the Phillies, so it is questionable whether he can be used in this dataset. There may be other similar examples (Greg Maddux?) that I have not yet studied.

At this point, some readers might be thinking that the first two pitchers mentioned here were also very young in the catcher’s initial year, and of course Tiant by 1978 was who knows how old. This is true, and it could be the topic of a future study, although there certainly were counterexamples in this database. And this leads to my next line of analysis.

ROOKIES COMPARED TO THE YEAR PRIOR

Next comparison: I compared the ERAs of pitchers who had 100 innings pitched in both the catcher’s rookie year and with the same team the previous year.

Overall results:

- There were 73 qualifying pitcher–catcher pairs. Of these, 22 were the same used in the previous dataset.

- Of the 73 pitchers, 47 had a higher ERA with the rookie catcher than with his predecessor.

- The composite ERA of these 73 pitchers was 0.37 higher with the rookie catcher.

- Assuming a normal distribution, this 0.37 difference is well beyond the bounds of chance (greater than 3 sigma).

This extra comparison, while not quite apples to apples, does at least answer the objection made previously: If it were true that the pitchers in the first study were improving as they naturally matured along with the catchers, then we would also expect them to have been even worse when they were a year younger. Instead, the opposite is the case. There are more data for this second comparison, since it is easier to find pitchers who threw 100 innings in consecutive years than for four or more years apart.

CONCLUSIONS

Catchers, as a whole, somehow are “worse” at helping their pitchers when they are major-league rookies. Pitchers, having worked previously with who knows what catcher, have their ERA go up when throwing to the new guy. However, after throwing to the new guy for a few years, their ERA goes way down. Maybe 40 or 50 or 60 runs per year, if you add up the effects for a whole pitching staff. No defensive player saves 50 runs a year. No catcher prevents stolen bases or passed balls, or blocks the plate, to anywhere near the tune of 50 runs a year.

The last team to win a pennant with a rookie catcher, even bending the definition of rookie a bit, were the 1990 Reds, for whom Joe Oliver had caught 47 games the previous season. This is 36 pennants ago. At hardballtimes.com, Matthew Namee recently published a note stating that only two teams using catchers age 22 or younger had won a World Series: Tim McCarver’s Cardinals in 1964 and Mike Scioscia’s Dodgers in 1981. McCarver had already spent parts of four years in St. Louis, and Scioscia was not a rookie in 1981 either.

You want an advantage for your fantasy-league team next year? Stay away from pitchers throwing to rookie catchers. Do I know why this happens? No. But handling pitchers in the majors does seem to be a learned skill.

Note

This article is adapted from an article that appeared in By the Numbers, (November 20, 2004), the newsletter of SABR’s Statistical Analysis Committee.

Database list of players used

(Click image to enlarge)