A Baseball with a Story: Fireworks in Philadelphia, July 4, 1911

This article was written by Eric Marshall White

This article was published in Spring 2011 Baseball Research Journal

The old ball was perched on a low, dusty shelf in a not very distinguished antique shop in Philadelphia; I spotted the ball only by chance just as I was about to leave the store. Even though I was an impoverished college sophomore who had no business spending $40 on a used baseball, I figured any ball as old and brown as the ones I’d seen at Cooperstown was worth a quick glance.

I was surprised to find that the ball bore a long black ink inscription winding its way along the curving contour of the seams:

This ball was a home run knocked into the center field bleachers by Fred Merkle the N.Y. Giants 1st baseman, and was caught by Fred T. Brown. July 4th 1911 – 2nd Game Double Header. This was the day that both the Athletics and Phillies took the lead.

Suddenly, I knew this $40 sacrifice was worth it. While my girlfriend looked on with more than a little disbelief, I emptied my wallet for the prized ball, trying my best not to let the proprietor catch on that he was dealing in relics far more precious (to me) than he knew.

Suddenly, I knew this $40 sacrifice was worth it. While my girlfriend looked on with more than a little disbelief, I emptied my wallet for the prized ball, trying my best not to let the proprietor catch on that he was dealing in relics far more precious (to me) than he knew.

Frederick Charles Merkle, born December 20, 1888, in Watertown, Wisconsin, was one of early baseball’s most famous figures. He was not a great player, but rather a very good one who became baseball’s greatest laughingstock, the patron saint of life’s wrong turns, inopportune disasters, and public embarrassments. I surmised that the shop owner had little or no baseball in his religion, or at least that he had not bothered to educate himself about Merkle’s infamous failure to step on second base in a crucial game of the epic 1908 National League pennant race.

Inexpressibly excited about the piece of American history nestled in my coat pocket, I told tales of Merkle all the way home.

The ball was dark brown all over and shiny like a well-varnished antique. The “Official National League” label was worn almost beyond recognition, and the seams were not the familiar red zig-zags found on virtually every baseball since the 1930s. Instead, the stitches alternated red and blue, betraying the ball’s manufacture in the Merkle era. Mud-stained, tobacco-splattered, and scuffed, the ball clearly had been through more than an inning or two of diamond warfare. It brought to mind a passage in Lawrence Ritter’s classic The Glory of Their Times, in which Merkle’s teammate Fred Snodgrass recalled how hard it was to see the dark brown balls in the afternoon shadows:

We hardly ever saw a new baseball, a clean one. If the ball went into the stands and the ushers couldn’t get it back from the spectators, only then would the umpire throw out a new one. He’d throw the ball out to the pitcher, who would promptly sidestep it. It would go around the infield once or twice and come back to the pitcher as black as the ace of spades. All the infielders were chewing tobacco or licorice, and spitting into their gloves, and they’d give that ball a good going over before it ever got to the pitcher.

This is much more interesting than today’s “game-used” balls, which are hardly used at all, being banished as soon as they show so much as a nick or a smudge.

Against the brown patina of my new 1911 ball, the printed black letters of Fred T. Brown’s inscription betray a slow-paced clumsiness—though not quite childlike—which suggests a certain lack of practice. Given his eagerness to record the details of his quarry, it seems our scribe was not an indifferent older spectator, but a dedicated young fan.

All that night my curiosity about the 1911 game ball ran wild. Had Christy Mathewson pitched for the Giants that day?

The next morning I went straight to the university library to look up the box score in the archival microfilms of the Philadelphia Inquirer. There, amid the front page news of Independence Day aeroplane exhibitions and boat races, I found the jubilant headline reporting that both of Philadelphia’s teams, the Phillies and the Athletics, had taken over first place that Tuesday, just as the ball’s inscription had boasted.

The Phillies had swept a doubleheader from John McGraw’s Giants in front of 18,000 fans at National League Park (rechristened the Baker Bowl in 1913) on Huntingdon and Broad streets, and Jack Coombs of the A’s had won both games of a twin bill over the Highlanders up in New York:

| National League | |||

| Team | W | L | GB |

| Phillies | 43 | 26 | — |

| Cubs | 42 | 26 | 0.5 |

| Giants | 42 | 27 | 1 |

| American League | |||

| Team | W | L | GB |

| Athletics | 47 | 22 | — |

| Tigers | 47 | 23 | 0.5 |

| White Sox | 34 | 30 | 10.5 |

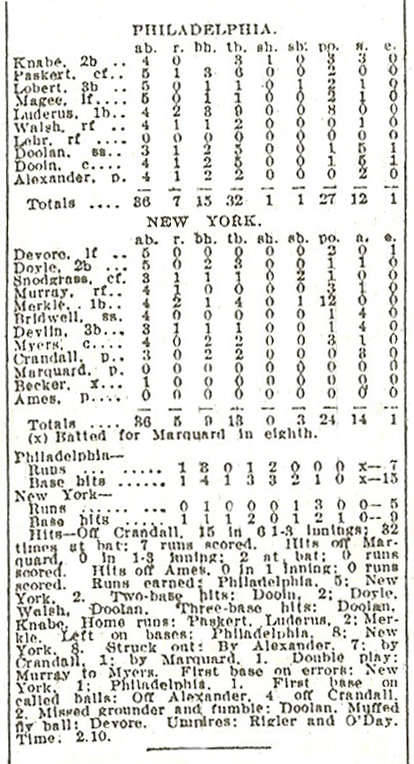

The story continued in the sports pages. The account of the Phillies game described Merkle “lacing a wallop into the bleachers in the seventh” with two runners on base. That phrase alone, forever engraved in the annals of the sport, made it all worth my forty bucks! But now I wanted to learn everything else about Merkle’s homer and its circumstances. My eyes raced through the lengthy game summary and checked the box score. The first question? Who had thrown Merkle the gopher ball so long ago? Surely he was some forgotten nobody whose lowly stature had not merited a mention on Fred T. Brown’s souvenir ball.

As it turned out, the pitcher was a 24-year-old still only midway through his rookie year. Despite the punishing 96-degree heat, the freshman weathered Merkle’s late-inning blast to finish with a complete game 7–5 triumph over New York’s Doc Crandall, Rube Marquard, and Red Ames.

The victory improved his record to 16–4, and the writers were already calling him “the pitching wonder of the year.” Yes, the pitcher that July 4 was none other than Grover Cleveland Alexander.

The victory improved his record to 16–4, and the writers were already calling him “the pitching wonder of the year.” Yes, the pitcher that July 4 was none other than Grover Cleveland Alexander.

The baseball gods truly were smiling down upon me, as the ball I had acquired the night before had been thrown by one of the greatest pitchers in the history of the game, the storied hero of the 1926 World Series, and holder of National League records for lifetime victories and shutouts! Eager to possess some documentation that would authenticate the significance of my sacred relic, I photocopied the entire newspaper account, including the box score.

Although nothing carries more documentary weight in baseball than an official box score, I noticed that this one misspelled Chief Meyers’ name as “Myers” and contained some numerical discrepancies, the most obvious being Philadelphia’s fielding statistics. They gave catcher Red Dooin the identical totals as the shortstop Mickey Doolan, but the catcher must have had at least seven putouts on Alexander’s strikeouts, and he probably had no errors (only one was charged to the team) and somewhat fewer assists. In addition, this box score missed a catcher’s interference error charged to M(e)yers.

Other interesting notes from the game: while Philadelphia’s center fielder Dode Paskert, taking advantage of the rules of the day, bounced a ball into the left-field bleachers for a home run, first baseman Fred Luderus walloped a pair of homers onto Broad Street in right, becoming the first player to hit two balls out of Philadelphia’s home park on the fly in the same game. New York’s starting pitcher Doc Crandall slammed a liner high off the big Bull Durham tobacco sign in right center but later had to be carried off the field after being hit in the head by a line drive that, amazingly, left-fielder Josh Devore almost caught on the fly. Crandall, therefore, was almost credited with an assist while getting knocked unconscious.

Like the old box score, the newspaper report of the game was a marvelous find in its own right. The Philadelphia Inquirer’s writer covering the Phillies, Edgar F. Wolfe, signed his article with the pseudonym “Jim Nasium.” He was also a cartoonist of some talent, who (in the absence of game photos) illustrated his account with a caricature of a toothless New York Giants player being blasted from below by an exploding Phillies firecracker.

Wolfe had a distinct gift for slangy ballpark lingo. From his prolix typewriter flowed a tangled ribbon of old-fashioned diamondese, the likes of which one just doesn’t see any more. He renamed the Giants the “Joints” while the home team became “Dooin’s Drubbers” after their catcher-manager. An error was either a “bum chuck” or “foozle.” Hometown hitters with “venom in their bludgeons” connected for a “psychological pelting” of the New York pitchers that included a “timely two-base soak” and a “three-cushion shot.” The 18,000 fans felt “effervescent joy” whenever a Phillie “pasted one on the snoot” and more runners “pattered over the pan.” The colorful Mr. Nasium described Merkle’s home run like this:

Wolfe had a distinct gift for slangy ballpark lingo. From his prolix typewriter flowed a tangled ribbon of old-fashioned diamondese, the likes of which one just doesn’t see any more. He renamed the Giants the “Joints” while the home team became “Dooin’s Drubbers” after their catcher-manager. An error was either a “bum chuck” or “foozle.” Hometown hitters with “venom in their bludgeons” connected for a “psychological pelting” of the New York pitchers that included a “timely two-base soak” and a “three-cushion shot.” The 18,000 fans felt “effervescent joy” whenever a Phillie “pasted one on the snoot” and more runners “pattered over the pan.” The colorful Mr. Nasium described Merkle’s home run like this:

Alexander was effective throughout the affray, save in the seventh, when, with two down, a freak break in the fortunes of war and a little perspiration in the eyes of Ump Rigler on a third strike or two on Murray allowed the Giants to chase in three runs. But ‘Alex’ wasn’t in danger even then … Snodgrass got a scratch hit by bounding one that Alexander checked just enough to turn it into a hit, and then Snodgrass stole second, as what Dooin thought was the third strike came over on Murray, Charlie not throwing because he thought the side was out. Rigler, however, called it a ball, and then Murray walked on another that looked mighty good. Merkle then caught one under the lug and lifted it into the bleachers, scoring Snodgrass and Murray ahead of him.

The New York Times described the same blast by Merkle more precisely as a “long drive” into the left field bleachers. Since Fred T. Brown recorded that he was sitting in center field when he caught or retrieved the home run—and what a thrill that must have been!—let’s split the difference and call it left-center.

Those bleachers, built in 1910, were 408 feet from home plate in center, and 379 to left-center, meaning that even though the homer was hardly Ruthian, it

certainly was a long drive for the time. Although home run totals shot up in 1911 (a record 316 were hit in the National League, as opposed to 214 in 1910 and 150 in 1909), their relative rarity in those days is shown by the fact that Giants hit only 16 four-baggers on the road that year, with Merkle’s July 4 rocket one of only four of the three-run variety.

Although Merkle, fearing for his safety and having lost 15 pounds from stress, wanted to quit baseball after his 1908 blunder, John McGraw gave him a $300 raise and had the foresight to stick with him as he developed into a right-handed power-and-speed standout.

He walloped a career-high 12 homers in 1911, ranking fifth in the league (Wildfire Schulte led with 21), one better than Home Run Baker’s high for the American League. Leading the Giants with 84 RBI, he put on two memorable power-hitting displays, doubling and tripling in one inning on June 5 then setting a record on May 13 (since broken) with six RBI in a single inning via a homer and a double. He also stole 49 bases in 1911.

Widely considered the fastest man in the league after Honus Wagner, Merkle swiped 272 bases during his sixteen-year career, including eleven thefts of home. No matter what else he did out on the diamond, however, the newspapers and fans knew him only as “Bonehead” Merkle. Finally, in 1950, after avoiding ballparks and reporters for decades, he agreed to attend an old-timers game at the Polo Grounds and was greeted with a touching and unforgettable standing ovation. He died on March 2, 1956.

Grover Cleveland “Pete” Alexander, born the February 26 1887, in Elba, Nebraska, likewise owed the majority of his fame to a single moment in baseball lore. Unlike poor Merkle, however, Pete emerged as the hero, saving the seventh game of the 1926 World Series for the Cardinals by striking out Yankee slugger Tony Lazzeri with the bases full in what his Hall of Fame plaque calls the “final crisis at Yankee Stadium.”

Grover Cleveland “Pete” Alexander, born the February 26 1887, in Elba, Nebraska, likewise owed the majority of his fame to a single moment in baseball lore. Unlike poor Merkle, however, Pete emerged as the hero, saving the seventh game of the 1926 World Series for the Cardinals by striking out Yankee slugger Tony Lazzeri with the bases full in what his Hall of Fame plaque calls the “final crisis at Yankee Stadium.”

It was a truly dramatic moment, especially for a 39-year-old all-time great who had never won a championship, but it was only the seventh inning, and Alex had already provided plenty of heroics by winning both of his Series starts. The notoriety of this single confrontation (re-enacted by Ronald Reagan in the 1952 film The Winning Team) nearly overshadows the pitcher’s three 30-win seasons, his 28 wins as a rookie in 1911 (a post-1900 record), his record 16 shutouts in 1916, and his 373 lifetime victories.

As a rookie in 1911, Alexander allowed only five home runs in 367 innings. According to the SABR Home Run Encyclopedia, Alexander was Merkle’s favorite target, serving up five of the first baseman’s 61 career long balls. In those deadball days, neither man could have been unaware of such a concentration of gophers, so it is likely that Merkle and Alexander grew to feel a sense of rivalry.

The two men faced each other down six or seven times a year for seven seasons, and in 1915, Merkle broke up one of Alexander’s many unsuccessful no-hit bids. Although they became teammates on the Cubs in 1918, their final “encounter” was in the famous seventh game of the 1926 World Series. Merkle was on the bench as a Yankees coach, hired by skipper Miller Huggins on account of his baseball acumen.

He was eligible to play, and we might picture Merkle saying to himself, “C’mon, Hug, put me in there! I used to pound this guy!” A key hit would have been a nice way to redeem 1908, but he never got the chance.

Although my old brown baseball’s day of baptism, the Fourth of July in 1911, was exactly a century ago, the game of baseball was different in so many ways it seems like an eternity. Yet fans like Fred T. Brown were not unlike us: they shared our love of the national game, cheering for the home team in the Independence Day heat, and they too felt that wary thrill whenever a ball came spinning their way.

Unlike Mr. Brown, I have never caught a home run or even snagged a foul ball after it came to rest amid the peanut shells. But just as he took care to inscribe his baseball, I always mark my ticket stubs with some salient occurrence of the day’s game. Pulling out three faded tickets from 1990, I see that I made note of the record ten double plays (nine of them grounded into) produced by the Red Sox (6) and Twins (4) on July 18, one night after the Bostonians had grounded into a record two triple plays … of Boston’s tenth straight victory in a Sunday game against the Yankees on September 2 … and of the best time I ever had at the old ballgame, the “Jeff Stone Game” on September 28 (ask a diehard Red Sox fan).

The old Alexander-Merkle ball, now in a display case on the fireplace mantel in my home, is a silent souvenir of that roaring hot day of a century ago. Like all worthy pieces of archaeology, the ball offers those who contemplate its history a much clearer picture of long-ago events. By piquing our curiosity about the pastime of an earlier era, these pieces of history inform us about important aspects of our own traditions. Such an artifact also connects us with our historical heroes, who suddenly become living and breathing people with imperfect destinies, not just names with records attached.

Of course, all of this comes from our awareness of the ball’s original context. For this we must thank Mr. Fred T. Brown of Philadelphia for his foresight in documenting his trophy with the particular circumstances of its time and place. That is what makes the old baseball relic so precious: not the imagined monetary value added by its associations with Hall of Famers and legendary “losers,” but its ability to retell a story of our national pastime which otherwise might be forgotten.

ERIC MARSHALL WHITE, PH.D., is a rare book librarian at Southern Methodist University in Dallas whose research usually involves Gutenberg and the development of printing in 15th-century Europe.

SOURCES

Charles C. Alexander, John McGraw (New York: Viking, 1988).

Herbert Bursky, “The Day Fred Merkle Returned to the Polo Grounds,” Baseball Digest, December, 1970.

Jack Kavanagh, Ol’ Pete: The Grover Cleveland Alexander Story (South Bend: Diamond Communications, 1997).

Christy Mathewson, Pitching in a Pinch (New York: Putnam, 1912).

The New York Times, July 5, 1911.

The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 5, 1911.

Lawrence Ritter, The Glory of Their Times (New York: MacMillan, 1966).

Lawrence Ritter, Lost Ballparks (New York: Viking, 1993).

The SABR Home Run Encyclopedia. Edited by Bob McConnell and David Vincent (New York: MacMillan, 1996).

John C. Skipper, Wicked Curve: The Life and Troubled Times of Grover Cleveland Alexander (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006).

Craig R. Wright generously provided useful information about fans returning baseballs hit into the stands in the early days.