A Brief History of the Washington Stars

This article was written by Maxwell Kates

This article was published in The National Pastime: Monumental Baseball (Washington, DC, 2009)

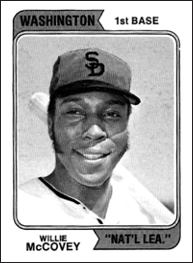

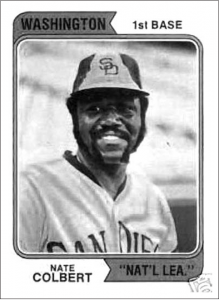

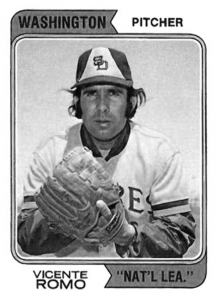

Have you ever wondered why Willie McCovey and ten other Padres were identified on their 1974 Topps cards as “Washington National League”?

Have you ever wondered why Willie McCovey and ten other Padres were identified on their 1974 Topps cards as “Washington National League”?

The history of the American League in Washington was not among the more glamorous chapters in baseball. In 71 seasons, two franchises called the Senators combined for only three American League pennants and only one World Series championship, in 1924, By contrast, the original American League Senators, who moved to Minneapolis-St. Paul in 1960, ended 24 of 60 seasons in seventh or eighth place. Only once, in 1946, did either Washington franchise draw better than one million spectators. As elected representatives and government officials comprised a fair representation of the fans at Griffith and RFK stadiums, there were likely at least as many cheering for the visiting teams. An expansion franchise was awarded to Washington in 1961, and after eight second-division finishes, the Senators showed flashes of brilliance in 1969 by winning 86 games for new manager Ted Williams. Earlier that year, the team was sold for $9 million to Minneapolis hotelier and Democratic National Committee treasurer Robert Short. The 1969 Senators proved to be a one-year wonder, returning in 1970 to their habitual doormat as “first in war, first in peace, and last in the American League.” Despite high-profile trades, which brought Curt Flood and Denny McLain to the District of Columbia in 1971, the Senators finished 63-96. Only the presence of the Cleveland Indians spared them last place in the American League East.

High ticket prices to see a mediocre team, and an unsafe neighbourhood, kept fans away to augment the losses on Short’s financial statements. The result: a September announcement that Short was moving the Senators to the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. Washington fans saved their worst for September 30, the final American League game played in Washington, when unruly behavior caused umpire James Honochick to forfeit a 7-5 lead to the visiting New York Yankees.

The city of Washington and its business leaders spent the next 33 years courting existing and expansion franchises to return Major League Baseball to the nation’s capital. Before the American League approved a bid to dispatch the Senators to Texas, it received a counteroffer from supermarket magnate Joseph Danzansky. Although he pledged to keep the Senators in Washington, his offer of $8.4 million was deemed “insufficient immediately” by American League owners and baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn. Also in 1971, Cleveland restaurateur Vernon Stouffer announced that he was selling the Indians. Had Danzansky’s bid succeeded, he would have transferred the Indians to Washington before Opening Day in 1972. However, the American League chose to approve a sale to lawyer Nicholas Mileti, who kept the team in Cleveland.

Commissioner Kuhn devised a plan in 1975 that would see every major-league team play two home games at RFK Stadium, but it didn’t happen. When the American League decided to expand in 1976, Washington was one of the finalists slated to join Seattle before junior-circuit owners voted on Toronto. After Edward Bennett Williams purchased the Baltimore Orioles in 1979, rumours persisted that the noted criminal lawyer would move the team to Washington until taxpayers voted in 1988 to approve the construction of a new stadium at Camden Yards. Professional baseball did return to the Washington area in 1984 with the arrival of the Prince William Pirates of the Carolina League. Minor-league clubs were subsequently awarded to the Maryland communities of Frederick and Bowie. When the Nationals played their first game in 2005, they ended a 106-year hiatus of National League baseball in Washington. However, the San Diego Padres in 1974 were the most likely candidate to relocate to the District of Columbia. During that summer of streaking, odd/even gasoline rationing, and a presidential resignation, Washington nearly fielded a team featuring Willie McCovey and Dave Winfield in its lineup and a pitching rotation bolstered by Randy Jones. To borrow a Bob Prince aphorism, they missed “by a gnat’s eyelash.”

Commissioner Kuhn devised a plan in 1975 that would see every major-league team play two home games at RFK Stadium, but it didn’t happen. When the American League decided to expand in 1976, Washington was one of the finalists slated to join Seattle before junior-circuit owners voted on Toronto. After Edward Bennett Williams purchased the Baltimore Orioles in 1979, rumours persisted that the noted criminal lawyer would move the team to Washington until taxpayers voted in 1988 to approve the construction of a new stadium at Camden Yards. Professional baseball did return to the Washington area in 1984 with the arrival of the Prince William Pirates of the Carolina League. Minor-league clubs were subsequently awarded to the Maryland communities of Frederick and Bowie. When the Nationals played their first game in 2005, they ended a 106-year hiatus of National League baseball in Washington. However, the San Diego Padres in 1974 were the most likely candidate to relocate to the District of Columbia. During that summer of streaking, odd/even gasoline rationing, and a presidential resignation, Washington nearly fielded a team featuring Willie McCovey and Dave Winfield in its lineup and a pitching rotation bolstered by Randy Jones. To borrow a Bob Prince aphorism, they missed “by a gnat’s eyelash.”

The San Diego Padres initially capitalized on the city’s proud history as a Pacific Coast League franchise by sweeping the Houston Astros in its first three games. As the Padres sat atop the National League West, Coach George “Sparky” Anderson thought the Padres could play the 1969 season undefeated. Batting instructor Wally Moon reminded Anderson that “come August, we’ll be so far out, a search party couldn’t find us.” Moon was correct. Over the ensuing five years the Padres never won more than 63 games, finished within 28½ games of the divisional lead, escaped last place, or drew even one million fans. Tying the Montreal Expos for the worst National League record in 1969, at 52-10, the Padres were awarded first choice in the June 1970 amateur draft, and selected Mike Ivie, a young catcher from Atlanta. After turning professional, however, Ivie developed a mental block behind the plate. He had no trouble making the throw to third base or throwing out base runners at second, and he was equally adept at making the throw to first base, but what he couldn’t accomplish was throwing the ball back to the pitcher. Rick Monday compared Ivie’s catching skills to “a $40 million airport with a $30 control tower.”

Whenever the cellar-dwelling Padres developed clever promotions, it backfired. When the San Francisco Giants visited for a weekend series in September 1969, future Hall of Famer Willie Mays was sitting on 599 lifetime home runs. Giants’ manager Clyde King told Padres president E. J. “Buzzie” Bavasi that Mays would rest the first game, on a Monday night. The Padres’ front office decided to open the left-field bleachers for the second game of the series, offering a new Chevrolet to any fan lucky enough to catch Mays’ 600th home run. More than 1,200 tickets had already been sold when King called on Mays to pinch-hit in the top of the ninth on Monday. Facing Mike Corkins, Mays hit his 600th home run into a sea of empty bleachers. Promotion ruined.

The Padres were owned by banking magnate C. Arnholt Smith. The son of a German baker, Smith was born in Walla Walla, Washington, in 1899, and was raised in San Diego. Quitting school at age 15, he rose up the ranks from messenger and grocery clerk to purchase a controlling interest in the United States National Bank in 1933. Over the next two decades, Smith’s empire grew to include the Westgate Hotel and other real-estate properties, transportation companies, silver mines, and a tuna cannery. The man known as “Mr. San Diego” bought the Padres, then a Pacific Coast League franchise, in 1955 for $30,000. When the National League awarded an expansion franchise to San Diego in 1968, Smith produced the $10 million fee to purchase the big-league club. As a major-league owner, he was unwilling to spend the money necessary to fund player development.

After the Ivie fiasco, the Padres drafted infield prospect Doug DeCinces. Potentially an anchor at third base for years to come, DeCinces asked for a $6,000 bonus to finance his college. When the Padres could offer only $4,000, DeCinces signed with the Baltimore Orioles. In one of the last interviews conducted before he died, Bavasi blamed a lack of television revenue as a source of the Padres’ cash flow problems. “From 1969 to 1971, we were never featured on Game of the Week, so we never received any TV revenue.” At one point, San Diego management asked its players to wait until Monday to cash the checks they received on Friday. The Padres were able to sign bona fide prospects like Dave Winfield by 1973, but by then, the writing was on the wall.

After the Ivie fiasco, the Padres drafted infield prospect Doug DeCinces. Potentially an anchor at third base for years to come, DeCinces asked for a $6,000 bonus to finance his college. When the Padres could offer only $4,000, DeCinces signed with the Baltimore Orioles. In one of the last interviews conducted before he died, Bavasi blamed a lack of television revenue as a source of the Padres’ cash flow problems. “From 1969 to 1971, we were never featured on Game of the Week, so we never received any TV revenue.” At one point, San Diego management asked its players to wait until Monday to cash the checks they received on Friday. The Padres were able to sign bona fide prospects like Dave Winfield by 1973, but by then, the writing was on the wall.

One might wonder how a successful businessman such as C. Arnholt Smith was unable to pay his players and lose a star like Doug DeCinces over a $2,000 differential. In the spring, the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency forced Smith to step down as the chairman of the U.S. National Bank. At the time, Smith owned 28 percent of the 200,000 shares outstanding. According to Time magazine, the bank loaned greater than the legally permissible 10 percent of its assets to companies controlled by one individual, who happened to be C. Arnholt Smith. Meanwhile, the U.S. National Bank showed losses and uncollectible loans of $143 million, a majority of which were represented by bad debts on Smith’s companies. Smith also owed the Internal Revenue Service over $22.8million in unpaid taxes, plus interest. A staunch Republican and personal friend of Richard M. Nixon, Smith was also being investigated for illegal contributions to the President’s 1972 campaign. The National League made it perfectly clear that they wanted no part of C. Arnholt Smith, and after the U.S. National Bank declared insolvency, he was forced to sell the Padres. In 1979, he was convicted of tax invasion and grand theft, and served seven months of a one-year sentence. He died in 1996, at the age of ninety-seven.

On May 27, 1973, Joseph Danzansky presented an offer of $12.5 million, which Smith accepted. Danzansky paid a $100,000 deposit in exchange for a pledge that Bavasi would not conduct any player transactions without his approval. With Danzansky installed as the de facto owner, general manager Peter Bavasi soon announced that the Padres were bound for Washington in 1974. In 2005, broadcaster Bob Chandler told reporter John Maffei, “[Bavasi] told everyone to be quiet, not to tell a soul. Of course, it was on the news that night and in the papers the next morning. Two weeks later, we were in Philadelphia and since it’s two hours from D.C., the ballpark was crawling with media.” Meanwhile, the Padres continued to pare its roster to meet its debt obligations. In order to minimize the debt, Danzansky asked Bavasi to deal pitcher Fred Norman to the Cincinnati Reds, and infielder Dave Campbell to the St. Louis Cardinals. Bavasi overruled trading pitching ace Clay Kirby, a Washington native who could be a gate attraction.

As the 1973 season progressed, San Diego baseball fans continued to display their apathy toward the Padres by drawing as few as 1,413 spectators on September 1. Washington interests were so certain of acquiring the Padres for 1974, the nickname “the Stars” was chosen. Haberdashers designed a sky-blue road uniform with “Washington” emblazed across the chest, in red block letters. The Stars cap featured a red W, a golden star on a white peak, and a blue background (similar to the Atlanta Braves caps of the era). The Bavasis considered hiring Minnie Minoso and Frank Robinson to manage the Stars, while Topps jumped the gun on its 1974 cards by identifying several Padres as “Washington National League.” For one Padre, reality set in with a visit to the San Diego Stadium clubhouse in December of 1973.

“Everything in the office was boxed and taped shut,” remembers Randy Jones. “I’m a Southern California guy. Grew up in Orange County, played at Chapman College. Now the team was moving across the country. I was bummed.” History has demonstrated that the Washington Stars never played an inning in the National League. Moreover, when play resumed in 1974, the Padres remained in San Diego. What happened?

As the clubhouse contents were ready to be shipped, the City of San Diego filed an $84million lawsuit against the Padres for breaking its lease on San Diego Stadium. With Smith out of the picture, it became Buzzie Bavasi’s task to find an alternate ownership group committed to keeping the Padres in San Diego. He found one headed by Marjorie Everett, the principal stockholder in the Hollywood Park racetrack. Everett’s group, which included songwriter Burt Bacharach, matched Danzansky’s offer of $12.5 million.

As the clubhouse contents were ready to be shipped, the City of San Diego filed an $84million lawsuit against the Padres for breaking its lease on San Diego Stadium. With Smith out of the picture, it became Buzzie Bavasi’s task to find an alternate ownership group committed to keeping the Padres in San Diego. He found one headed by Marjorie Everett, the principal stockholder in the Hollywood Park racetrack. Everett’s group, which included songwriter Burt Bacharach, matched Danzansky’s offer of $12.5 million.

Opposition to the Everett consortium was vocal among National League owners. John Galbreath of the Pirates and Joan Payson of the Mets were particularly vociferous by expressing negative feelings over Everett’s dealings in the racing industry. Other owners became suspicious when Everett’s father was tied to a political scandal in Illinois. After the Everett group announced that it would only commit itself to San Diego for “a couple of years,” National League owners rejected her bid, 8-3. Ironically, the alternative bid prompted by the lawsuit may have been enough to keep the team from moving to Washington. Danzansky refused to indemnify the lawsuit, and demanded the refund of his down payment. The ownership saga was finally resolved on January 25, 1974, when the Padres were sold to McDonald’s magnate Ray Kroc for $12.5 million.

Three decades passed before Major League Baseball returned to Washington with the transfer of the Montreal Expos. Their expansion sisters remain in San Diego to this day.

Sources

Bavasi, Buzzie. Off the Record. Chicago: Bonus Books, 1987.

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella. Total Ballclubs: The Ultimate Book of Baseball Teams. Toronto: Sports Media Publishing, 2005.

Elliott, Bob. Blue Jays Trivia Quiz Book. Toronto: Toronto Sun, 1993. Forr, James. “Forfeits.” The National Pastime, no. 25, 2005.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball.

2nd ed. Durham, N.C.: Baseball America, 1997.

Kuhn, Bowie. Hardball: The Education of a Baseball Commissioner. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1987.

Maffei, John. “Padres were Washington bound for ’74.” North County Times, 4 August 2005. Internet. Accessed August 28, 2008.

Nash, Bruce, and Allan Zullo. The Baseball Hall of Shame. Vol. 2. New York: Simon Spotlight Entertainment, 1986.

Noble, Holcomb B. “C. Arnholt Smith, 97, Banker and Padres Chief Before a Fall.” New York Times, 11 June 1996.

Swank, Bill. Baseball in San Diego: From the Padres to Petco. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia, 2004.

Torry, Jack. Endless Summers: The Fall and Rise of the Cleveland Indians.

South Bend, Ind.: Diamond Communications, 1995. “The Westgate Scandal.” Time, 29 October 1973.