A Canadian National Treasure: Tecumseh/Labatt Memorial Park

This article was written by Riley Nowokowski - Robert K. Barney

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

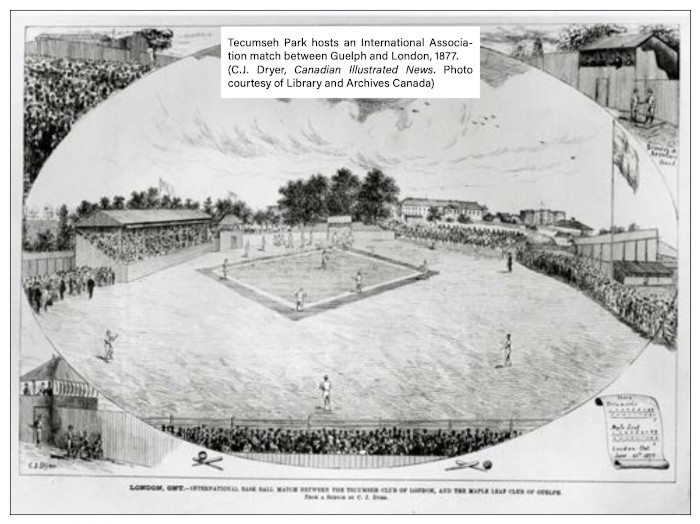

Tecumseh Park hosts an International Association match between Guelph and London, 1877. (C.J. Dryer, Canadian Illustrated News. Photo courtesy of Library and Archives Canada)

There resides in London, Ontario, across Queen’s Avenue from the old early nineteenth century courthouse located above the confluence of the north and south branches of the Thames River (locally referred to as “The Forks”), one of baseball history’s grandest historical legacies, the fabled Labatt Memorial Park, the oldest continuously operated baseball grounds found anywhere in the world. There it rests in all its contemporary luster, a luxuriant jewel in the Forest City’s urban landscape.

We initially became interested in the historical lineage of Labatt Park in the face of an American challenge to the Park’s embrace of the distinction “oldest and continuously operated.” Hence, we resolved to carry out a mission to pursue a detailed history of Labatt Park’s origin, and to examine the credibility of its unique longevity status. With regard to the latter, we carry out that exercise in the accompanying appended commentary.

Beyond that secondary quest, however, we chiefly endeavor to leave to posterity a documented account of the Park’s place in the cultural lineage of the city of London, the province of Ontario, the national state of Canada, and, perhaps above all, its place in the greater history of North America’s long-standing preeminent team sport: baseball. Let us begin.

The record of baseball play in London predates the opening of Tecumseh Park/Labatt Park by two decades. In the City of London Directory for 1856, we note the establishment of a London Base Ball Club. One game of baseball appears to have been played in that year, a two-inning affair in which London edged a team from the nearby diminutive hamlet of Delaware by a score of 34-33.1

Over the following two decades, 1856-1876, baseball play in London expanded rapidly, creating competition with the sport of cricket for players, fan followers, and, even more critically, for suitable practice and playing space. In general, cricket experienced a steady decline in the face of an ever-rising passion of public interest for baseball. By 1900 the sport of cricket hardly existed in London’s sporting landscape.2 Embedded in such passion for baseball rose the London Tecumsehs and the need for an exclusive playing venue. Hence, Tecumseh Park.

To recount Tecumseh Park’s genesis authenticity, we turn to the pages of the London Daily Advertiser of the spring months March, April, and May of 1877. With knowledge that London’s premier professional baseball aggregation, the Tecumsehs, had been accepted as a charter member of the new International Association, a genuine “major league” competitor to the equally new (1876) National Association of Professional Base Ball Clubs (today, Major League Baseball’s National League) for urban franchises and baseball’s best players, the London Daily Advertiser of March 31 sought to educate its readers on the forthcoming 1877 season’s prospectus by offering for sale at 10 cents per copy the Canadian Baseball Guide, containing the “Constitution and Championship Code of the International Association,” the “Playing Rules of the League,” and “other valuable information connected with the Game.”3 There is little doubt that the prospect of the Tecumsehs playing in the new International Association sparked great interest among London’s sporting public.

Two weeks and two days later, on April 16, in a column headed “The Ball Field,” the Advertiser provided its readers with the “inside scoop” on reasons why a new baseball park was needed. Such a need was associated with limited Tecumseh practice and playing time on London’s only viable fieldsports venue, today’s greater Victoria Park area, which in 1877 served chiefly as the expansive parade grounds and drill field for the Crowns military garrison. Consequently, a new playing venue had to be secured, one with total Tecumseh control over its availability. Stated the Advertiser.

The vexatious delays in getting possession of part of the Park property, and the threatening attitude of certain parties who appear determined to have the ball ground at their own disposal, so as to benefit by the custom which large crowds invariably draw to people in their line of business, compelled the abandonment of the idea of utilizing the waste lands of the city for a ballfield. The conditions imposed by the Park Committee, one of which limited the size of the field to such narrow dimensions that it would be too small for either baseball, cricket or lacrosse, added another reason why it would be folly for the club to go to the expense of enclosing and preparing the portion of the Artillery Block set apart for its use. After visiting London East, the northern suburbs of the city and the Petersville and Kensington Flats, the most convenient plot, taking everything into consideration, that could be secured, was a piece of meadow land adjoining the west end of Kensington Bridge, on the north side of the road, and an agreement has been effected by the owners of it for its lease or purchase. Work will be commenced on it at once, and the expectation is that it will be ready in ten days, or a fortnight at the furthest. It is nearer to the business centre of the city than the exhibition grounds, and when the Street Car Company extend their track to the brow of the Court House hill, which would be to their interest to do, it can be reached from all parts of the city readily and comfortably.4

With respect to the site choice made by the Tecumseh Base Ball Club (“a piece of meadow land adjoining the west end of Kensington Bridge, on the north side of the road”) we are offered a then contemporary view of that particular piece of land that captured the favor of Tecumseh officials. There it lay, in its bucolic circumstance at the forks of the Thames River, the future site of Tecumseh Park, occupying a parcel of land that appeared to be endowed with a field of barley or winter wheat ready for harvesting, all painted in oils by the artist Charles B. Chapman in the late summer of 1875, a scant two years prior to the park’s celebrative beginning.5

Returning our attention to a historic newspaper comment on the site selection of the park, published on Friday, April 20, the Advertiser was once again prompted to comment on developments at the new ballpark location:

The rain of the past two days has retarded the work of preparing the new grounds for the Tecumsehs, but an extra force is at work today endeavoring to make up for lost time. The contract for two thousand yards of sodding has been let to Mr. Murdoch. The fencing and stands for the accommodation of spectators will be rushed rapidly forward. There is a brisk competition for the lease of the refreshment stands on the grounds. Everything is expected to be in readiness by the first of May.6

As the new Tecumseh ball grounds, named appropriately Tecumseh Park, were being established, the professional Tecumsehs played a practice contest on the old Military Park grounds. The result, an 8-2 victory over the Atlantics, “an amateur team of this city,” was played out before “a large attendance of spectators.”7 Baseball-fever-related activities surrounding the new Tecumseh Park under development continued to appear in the Advertiser, particularly with regard to the games planned for the gala inauguration of the facility:

The Great Western Railway have ordered reduced rates at all stations on their main line and branches for the 5th and 7th of May, to give people an opportunity of witnessing the base ball games between the Hartfords and Tecumsehs. Proposals are invited for leases of the refreshment stands on the Tecumseh’s new grounds; also for the privilege of decorating the fences with advertising announcements.8

On the last day of April, as the series against the Hartfords drew ever nearer, the Advertiser updated its readers on the new park’s condition:

The Tecumsehs’ ball grounds are beginning to look as pretty as a picture. The diamond is beautifully sodded and the clay paths around the bases serve to bring out the rich green surrounding them with double effect. The grandstand is a fine commanding building, and comfortably suited. The reporters and scorers, and telegraph operators are also well provided for. A large tier of open seats is being erected in the southeast angle. Though the grounds will be ready for playing on next Saturday, when the Hartfords open the season with the Tecumsehs, they will not be in their best condition for some weeks to come. The progress made during the past two weeks is something wonderful.9

But first, a critical moment in Tecumseh Park history – its first documented competition – a practice game between the Tecumsehs and London’s amateur Atlantics on the afternoon of Thursday, May 3, 1877. The outcome, a 5-1 victory for the Tecumsehs, is inconsequential to our study here, but the Advertiser’s commentary on Tecumseh Park itself is enlightening. On the eve of the “official” opening of the season against the Hartfords, one gets a full picture of the now classic baseball venue:

The new grounds are nearly complete in every respect of any of the kind in Canada, and but few American cities have such a convenient playing field. The place has been levelled under the management of Mr. Kitchen, who has worked hard in getting things into shape. The diamond and several feet around the borders are nicely sodded, while the base lines have been formed of clay, and are as hard as a rock. Mr. Murdock deserves a great deal of credit for the way he has done the sodding. A pipe well has been sunk, and a full supply of cool water is thus always in the ground; the well will also be useful in watering the grounds. A grandstand capable of seating 600 persons has been erected in the northeast corner of the field. This is for the use of members of the club and the seats have already been reserved for the entire season. At the southeast corner is the general stand, open to the general public in payment of a fee. To the south of the grandstand, which by the way is covered, is a Directors’ Pavillion, erected at the expense of the President, Mr. J. L. [Jacob Lewis] Englehart, who with Mr. Plummer, has given a good deal of attention to overseeing the fitting up of the grounds and buildings.

Directly behind the catcher is a booth to be used for a dressing and store room by the players, and above this is a point of observation for scorers, telegraph operators and reporters. It is hoped that they will be left alone by outsiders, as [they are] persons who have work to do and don’t care to be bothered by people shouting, applauding or criticising the play.10

On the afternoon of Saturday, May 5, 1877, the Tecumsehs met and were defeated by the Hartfords by a score of 6-2. The Advertiser reported that “fully two thousand persons” attended.11 Two days later, on the afternoon of Monday, May 7, the second game of the two-game series unfolded, an 8-4 series sweep victory for the Hartfords. The Advertiser, while reporting a crowd of “probably fifteen hundred,” extolled the visitors as “a fine body of men, quiet and gentlemanly in their manner, and never once in their two games did they question a decision or make a remark to which any exception could be taken.”12

There followed in London a two-game Friday/Saturday series against the Stars of Syracuse (New York), both contests of which the Tecumsehs won by scores of 7-2 and 9-8.13 And then, scarcely two days later, on Tuesday afternoon, May 15, “at 3:00,” Tecumseh Park spectators, among them “a large number of Maple Leafs” from Guelph, witnessed a 2-0 Tecumseh defeat at the hands of the Pittsburgh Alleghenys in “the first game of base-ball in this city in the international series.”14 And thus closed the first and earliest chapter in the history of what we know today as Labatt Park.

FLOODS, CYCLING, AND BASEBALL FEVER

TECUMSEH/LABATT PARK, 1877-1937

From the pages of the London Advertiser of the latter part of the nineteenth century15 and the London Free Press for much of the twentieth century16 comes the primary record that supports beyond all argument the record that preserves the distinction “continuously operating” that the hallowed park has rightfully earned. A thorough examination of two floods in question prove beyond a shadow of doubt that in both cases, the “one and the same” Tecumseh Park (1883) and John Labatt Memorial Park (1937) were in timely fashion renovated following the destructive inundations that in both cases interrupted scheduled activities. This study puts to rest the argument that the storied baseball park changed physical location.17 Such findings provide further evidence undergirding the bona-fide heritage distinction the park enjoys.

For the first five years of its existence (1877-1882), Tecumseh Park was the hub of London’s sporting activity. During that five-year period, not only was it the most active and prestigious venue for baseball, it also hosted the central activities of two other prominent sporting pursuits and their supporting constituencies, the “bicycle and lacrosse crowds.” London, like much of North America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, embraced the period’s cycling craze. The cycling pastime experienced phenomenal growth in the city and its surrounding areas during much of the 1880s and 1890s; in fact, few recreational sporting activities rivaled cycling in terms of numbers of participants, individual club organization, and investment in facilities.18

London’s Forest City Bicycle Club headquarters, located in a large three-floor warehouse on Dundas Street, formerly a wholesale dry-goods establishment, was the envy of most of the city’s sporting aggregations. Referred to as “elegant and spacious,”19 the top floor was fitted out as a club room, the lower two floors for riding activities.20 Part of the club’s activities focused on track racing, much of which was presented in Tecumseh Park before enthusiastic crowds.

Lacrosse, riding the pinnacle of its success in mustering Canadian sporting attention over that of other “national sport claimants” in the 1860s and 1870s, also focused squarely on Tecumseh Park for its main competitive attractions.21 Members of the London Lacrosse Club, meeting on April 10, 1883, reported the Advertiser, “crowded into meeting rooms, showing that the national game has taken a strong hold on the lovers of sport in this city.”22 Club secretary Wylkie reported that the Management Committee had “… secured the entire [exaggerated] control of Tecumseh Park for the coming season. …”23

At a subsequent meeting, some two weeks later, the London Lacrosse Club announced an effort to “put Tecumseh Park in order, and have the stands moved and grounds scraped, so as to commence practice as soon as possible.”24 On May 3 the Advertiser reported that “the newly organized lacrosse club yesterday received a consignment of three dozen sticks from Brantford, where they are manufactured by the Indians. The sticks are pronounced in every respect first class. The first practice of the club will take place tomorrow morning on Tecumseh Park, and again on Saturday.”25 And on May 12: “The costume selected by the club consists of navy blue knickerbocker, blue and white striped shirt, blue stockings and polo dips. …”26

Learning of plans for a spectacular opening of the Lacrosse Club’s 1883 competitive season, the May 14 issue of the Advertiser reported the following: “Between thirty and forty members assembled for practice Saturday afternoon on Tecumseh Park. After practice, the President, J.B. Vining called the members together for the purpose of electing a captain, which resulted in the choice of Mr. P.J. Edmonds, who is in every way qualified for the position, and a zealous lacrosse player.”27 The “Grand Opening” occurred on May 24 against the Brants of Brantford, an affair that drew a reported crowd of about 2,500 to “the Tecumseh grounds.”28

Meanwhile, as Tecumseh Park played host to bicycle and lacrosse activity, it also accommodated the activities of London’s foremost baseball nines. The city’s 1882 champions, the Mutuals, determined to “retain the laurels won last year[,]” [were hoping] “to commence practice as soon as the state of weather permits” [while declaring an intent] to “secure, if possible, the Tecumseh Park.”29 During the month of May 1883 Tecumseh Park was the center of London’s busy baseball activity. A number of local baseball aggregations featured the play of both young adherents to the game, for instance on teams such as the Young Athletes and Young Tecumsehs, as well as older experienced players on such baseball clubs as the Eurekas, Alerts, Atlantics, and, of course, London’s “diamond pride,” the senior Tecumsehs.

What appeared to be a rosy and active athletics life for Tecumseh Park for the season of 1883 was torn asunder by events occurring on the evening and early morning of July 10/11. In what the Advertiser proclaimed “a catastrophe altogether unknown at this season of the year,” an “uninterrupted torrent of rain fell throughout the night, lasting until mid-morning the next day.”30 London West, and with it, Tecumseh Park, were hardest hit; the water was said to have reached the highest point ever known: “The whole of Tecumseh Park, fences, stands, and houses, together with Massie’s boat house, all went down the river.”31

And it was not solely baseball that suffered the consequences of the disaster. As the Advertiser reported: “All the effects of the London Lacrosse Club were swept away by the flood, including sticks, clubs, balls, etc. They were stored at Tecumseh Park, and were carried away with the buildings.”32 Tecumseh Park, for the moment, ceased to function. The remainder of the 1883 outdoor sports season in Tecumseh Park was suspended. London newspapers during that time were replete with reports of elite athletic contests normally contested in Tecumseh Park occurring instead on the grounds of rival teams.

Almost four months after the July 1883 flood, London city officials met on November 1 to decide on tax rates and priority expenditures, among which flood-related damage issues were prominent. The Advertiser reported that one subject of discussion was the plight of Tecumseh Park: “The baseball grounds should be looked after. The want of fence along the street renders walking after dark on the sidewalk a very dangerous matter.”33

A week later the London West Council met for further civic allocation purposes. No funds were allotted for Tecumseh Park, only a motion unanimously passed “that the Tecumseh Base Ball Club be notified to fence their property on Dundas Street, as it was in a dangerous condition.”34 As winter set in, thought and action toward rehabilitation of Tecumseh Park from the ravages of the great flood of July 1883 were put on hold until the following spring.

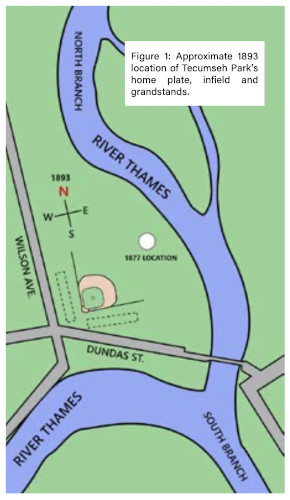

A decade after the 1883 flood, London’s foremost baseball venue underwent significant change – a geographical alteration in the location of the park’s baseball diamond. More than half a century later, in mid-December 1936, as the city rejoiced over the John Labatt family donation of Tecumseh Park to the City of London, the Free Press was moved to recall aspects of the park’s history. Accordingly, the following notation appeared: “Originally the home plate was at the eastern section of the park and the players batted towards the west. In 1893 the diamond was rearranged and the home plate was close to Dundas Street, with the teams batting towards the north. Later the home plate was placed within a few feet of where it is now.”35

Further documentation for this change from the park’s original 1877 infield location has yet to surface, but if the Free Press revelation is true, then the diamonds infield position within the park property’s confines changed from its original northeast location to a southwestern location in 1893. As seen in Figure 1, Dundas Street would have run somewhat parallel to the diamond’s right-field foul line; Wilson Avenue (in 1893, Central Avenue) ran parallel to the left-field foul line. Moving home plate away from the consistently menacing overflow of the Thames River might have been the motivation for such action, as well as placing the setting sun in the west in the eyes of the outfielders rather than the batters.36

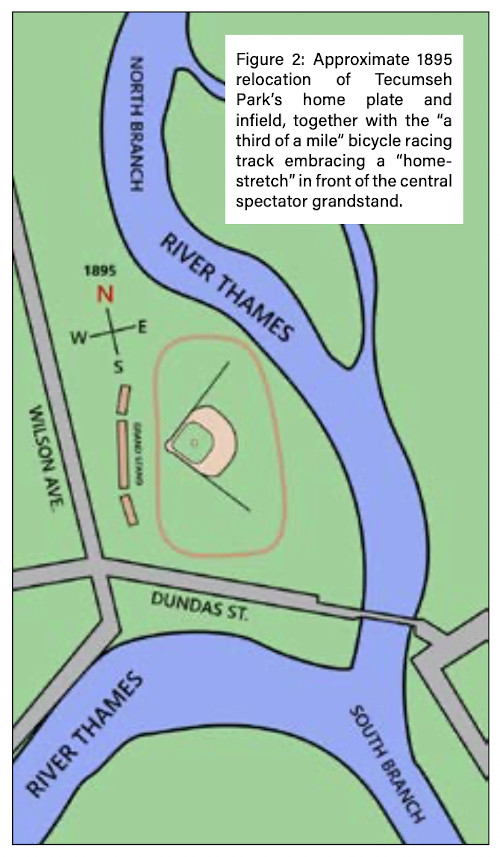

Probably the single most critical development in the park’s diamond sport history evolved not from the impetus of baseball, but rather from the widely popular late nineteenth-century sport of bicycling. We have previously noted the prominence of cycling affairs in London.37 In the latter part of May 1895, the London Advertiser reported on the opening of the ball season, grumbling: “With decidedly uncomfortable weather, and a somewhat one-sided exhibition of baseball, the season of 1895 was opened at Tecumseh Park Saturday afternoon. Though the temperature was chilly and rain threatened to fall every minute the same old grandstand and the same old bleachers held about the usual number of cranks, who, however, owing to the tameness of the match, had little opportunity to whoop er up.”38

And then, scarcely five days later, a startling Advertiser announcement: “It is a Go: The Much Talked of Bicycle Track Will be Built at Once.”39 An auspicious facility, “one of the best athletic parks in Canada” was projected to be finished in Tecumseh Park by late July.40 Auspicious indeed: “… a third of a mile brick-dust and cement track, complete with proper banking on the turns, and a baseball diamond mapped out, the infield arranged inside the perimeter of the track itself, together with a grandstand seating 2,500 folks, all at a cost of $3,000.”41 [See Figure 2.]

There was more! Specific enhancements render a graphic picture of the park’s new arrangement.42 Representatives of the London Bicycle Club, among them W.J. Reid, the owner of Tecumseh Park, were the conceptual architects and exclusive financers of the entire endeavor. Throughout June and July, well into August, London newspapers, particularly the Advertiser, reported the progress of the grand project,43 carried on without the need to curtail the park’s baseball activities. And then, finally, the grand opening of Tecumseh Park’s “new look.”

On Saturday afternoon, August 17, 1895, a procession of townsfolk and dignitaries led by the Musical Society Band formed at Richmond and Dundas Streets and marched to Tecumseh Park, arriving in pouring rain. A crowd of some 800 souls, considerably short of the several thousand expected, braved the weather to attend.44 London Mayor J.W. Little opened the formal ceremonies by orating on the prospective value of the cycling development to London youth and the debt owed to the facility’s initiators: “The cultivation of these qualities and their application to our regular duties should certainly under ordinary circumstances, lead to success in any calling. (Applause) We are, therefore, under obligation to those who furnish facilities for the development of young people in this way.”45

Then, J.M. Reid spoke to the spectators and explained: “I trust … this is only the start of an era of bicycle riding in the city, and I will gladly do anything in my power to further the sport. We will have in the near future, so Mr. Human has told me, a cricket club laying out their crease here. We already have a baseball diamond, and with a cricket crease and bicycle track we will have as good an athletic grounds as there is in the country.”46 Despite the August 17 attendance disappointment, subsequent bicycle race events held at Tecumseh Park’s new cycling track generated robust spectator crowds witnessing races for prizes, often bestowed in the form of ornate rings set with diamonds.47

Figure 2: Approximate 1895 relocation of Tecumseh Park’s home plate and infield, together with the “a third of a mile” bicycle racing track embracing a “homestretch” in front of the central spectator grandstand.

And so ended yet another chapter in the transformation of Tecumseh Park, one that brought the historic grounds closer to the perspective in which the park resides in these times. In closing this discussion of the bicycle club’s installation of its racing track and subsequent relocation of the park’s baseball diamond to the track’s elongated oval infield in 1895, it should be noted that possibly by 1916, cycling activity, along with the celebrated racing track, had disappeared from the park’s scheduled activities and physical landscape, the victim of a rapidly emerging preoccupation of Canadians and Americans alike with a relatively new technological fascination, the soon-to-be ubiquitous automobile.

Sometime prior to 1922, possibly dating to 1916, Tecumseh Park noted a reconfiguration of the park’s expansive grounds, the installation of a new facility to accommodate the play of the Western University Mustangs football team. A 1922 aerial photograph of Tecumseh Park demonstrates that the football facility was laid out across the baseball diamond, directly in front of the spectator grandstand. In the late 1920s, the Western Mustangs abandoned Tecumseh Park to instead play their contests in the university’s newly constructed J.W. Little Stadium, built on the campus proper and inaugurated in the autumn of 1929.48

By the mid-1920s the football arrangement in Tecumseh Park no longer existed, and, for all intents and purposes, the park stood as a facility almost totally focused on London’s ever-expanding baseball scene. Nevertheless, it remains ironic that one of the most significant “change agents” in the arrangement of the park’s modern baseball playing field location was the sport of cycling and its spectacular racing track, which disappeared completely from the sporting scene, the victim, in part, of the development of and infatuation with the automobile.

The most devastating disaster in London’s now two-century community history was the great flood of April 1937, an event that had repercussions for the city’s premier baseball precinct. The catastrophic late April flood was preceded by an event occurring scarcely five months previous, the donation of the park property to the City of London by a recent purchaser, the John Labatt family. In mid-December of 1936 the London Free Press blared the good news: “City Is Given Tecumseh Park, $10,000: Famous Playground Donated by Labatt Family to Citizens.”49 Officially renamed the John Labatt Memorial Park, it became known by most folks as simply Labatt Park. The Labatt family gift of $10,000 came in the form of an endowment sum to be used for capital improvements. Little did London city fathers know at the time that the endowment sum would be pressed into needed service within a few months.

The December announcement and local celebration of the Labatt bequest had hardly subsided, when, once again, as was annually anticipated, the city began to brace itself for the fallout from melting snow and ice and the onset of heavy spring rainfalls. In early January of 1937, omens of approaching disaster were placed before London newspaper readers: “Nearly Five Inches of Rain in 15 Days,” reported the Free Press.50 And, approaching mid-February, continuing alarm: “Heavy Rains Flood River Flats.”51 And finally, the late April 1937 catastrophe: “… the swollen waters of the Thames River overflowed its banks in a wild rampage today….”52

The preliminary flood damage cost rested at $3 million; newspaper descriptions underscoring the flood’s consequence detailed a great citywide tragedy,53 from which Labatt Park was not exempt: “Flood Plays Havoc to Ancient Grandstand … John Labatt Memorial Park now completely covered by water … grandstand has been cracked and temporary bleachers have been washed away….”54

Unlike the July 1883 flood, which nullified any further sports activity at Tecumseh Park until the spring of 1884, the early April 1937 London flood disaster did not have such sustained consequence for the newly christened Labatt Park. On the eve of the flood’s occurrence the Free Press reported on an inspection of Labatt Park by Frank Dark, construction superintendent of the Public Utilities Commission, and William Farquarson, London playgrounds supervisor. The property was “in bad condition. Fences need immediate attention, the roof of the grandstand leaks, fungus is growing on the grandstand seats.”55 Together with flood damage itself, pre-flood deterioration conditions added to a restoration urgency toward providing improvements and upgrading of the facility.

Ultimately, the park remained unavailable for all activity for a little over a month. During that period alternative arrangements were made for previously scheduled contests. The Free Press, for instance, noted that the London Senior baseball team would “play [their] first six games away from home,”56 the first home game to occur on June 19, 1937. Commencing in mid-June, the Seniors played the remainder of the 1937 season at Labatt Park.

LABATT PARK IN ITS MODERN FORM AND FUNCTION

After the flood, certainly by 1940, Labatt Park was once again transformed. The two spectator stands that previously extended from both sides of the central main grandstand (placed there originally to accommodate the homestretch of the bicycle racing track), were destroyed in the 1937 flood. Neither was resurrected in its original place. Instead, extended spectator stands were arranged contiguous to and behind the first base/right field and third base/left field foul lines. Home plate remained in roughly the same position as it did prior to the flood. A softball diamond was installed on the northern end of Labatt Park’s grounds, a facility that particularly related to the explosion of ladies’ softball in London and vicinity in the 1940s and early 1950s.57

Since the location of home plate in the park remains somewhat controversial, our research on the subject inclines us to argue that the home plate’s location and its accompanying infield changed at least four times in its now almost century and a half of history.

After the 1937 flood, Labatt Park’s baseball diamond remained generally located in its 1895 perspective, that is, with Wilson Avenue located directly west behind home plate, and batters hitting eastward. In 1937, too, at which time the city’s representative in the Intercounty League was known as the London Silverwoods, the storied dressing-room building was erected that still remains today as a complementary Labatt Park reminder of London’s baseball past. By 1940 the park was close to its present circumstance. Enlargements in spectator seating, dugout accommodation for players, and relocation of home plate to a slightly more northerly location were established in the decades of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

In 1989, just in time for the reemergence of professional baseball in Labatt Park, the City of London completed an important civic development that deflected on the historic baseball facility. The most important development between 1971 and 1989 was the extension of Queen’s Avenue with its own bridge westward over the Thames River to intersect with Dundas Street running parallel to it, thus forming a junction from which Riverside Drive extends through London West. The Queen’s Avenue extension necessitated removal of the small cluster of houses in the deep right-field corner, which in turn modified the dimensions of the right-field portion of the playing field. By 1989, too, the houses bordering Labatt Park on the east side of Wilson Avenue had been removed, greatly enlarging the park’s main entry precinct. Other developments between 1971 and 1989 were the construction of extended bleachers along both foul lines, a warning track around the perimeter of the outfield, and impressive landscaping beautification.

Figure 3: Changes in Tecumseh Park / Labatt Park home plate location: 1=1877,2=1893, 3=1895, 4=post-1937.

Many of baseball history’s luminaries have played in Tecumseh/Labatt Park at one time or another, including Hall of Famers Ty Cobb, Charlie Gehringer, and Canada’s own Fergie Jenkins. The longest-standing baseball tenant of Tecumseh/Labatt Park has been the London representative in the Intercounty Baseball League, an enduring organization established in 1919. The first London entry in the Intercounty League, the London Braves, commenced play in 1925.

Since then, depending on team sponsorship, London’s Intercounty team has been known at various times as the London Winery (1934-1936), the London Silverwoods (1937-1938), the London Army Team (1942-1943), the London Majors (1944-1959), the London Diamonds (1960-1961), the London Majors again (1962), the London Pontiacs (1963-1969), the London Avcos (1970-1973) and the London El-Morocco Majors (1974). Since 1975 the team has stuck with the London Majors moniker.

Late in the twentieth century, professional baseball returned to Labatt Park, a first since the time of its earliest occupants, the London Tecumsehs. In 1989 the London Tigers, a Double-A Eastern League affiliate of the American League Detroit Tigers, took up residence in a much improved and beautified Labatt Park. Improvements made for the arrival of the Tigers cost in the vicinity of $1 million. They included new lighting, concession booth enhancements, a 40- by 19-foot electronic Scoreboard (partially sponsored by Labatt Breweries), new dressing rooms, and new dugouts.

The Tigers in London were short-lived. The franchise moved to Trenton, New Jersey, for the 1994 season. In 1999 the London Werewolves of the fledgling Frontier League arrived in London. Their tenure in Labatt Park ended in 2001, a victim of limited attendance and skyrocketing operating costs. And in 2003 Labatt Park became the home of the London Monarchs of the equally short-lived Canadian Baseball League, which folded in midseason due to financial difficulties.

EPILOGUE

Finally, what is in store for the storied park and its illustrious historic distinction? How might it be protected from the ravages of urban expansion and corporate development? One answer, of course, is heritage distinction reinforced by authority. We understand that “reinforced authority” is bestowed at three levels: municipal, provincial, and national. Labatt Park connotes much more than simply a venue for baseball activity.58 It is a sanctified public space for the gathering of Ontarians, indeed greater Canadians, to experience and celebrate a national cultural pastime now approaching two centuries duration.

The City of London, Ontario, realizes this fact. Since its ownership of the park commenced in 1937, it has poured millions of dollars into the park and its immediate surroundings. London fully realizes its value to the urban life of its citizens. On May 30, 1994, the City of London, under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act, named Labatt Park an Ontario Heritage Landmark Site. One month later, on July 1, 1994, in an act of civic heritage authority carried out at the park, a plaque was unveiled at Canada Day ceremonies presided over by Mayor Tom Gosnell.59

Though Labatt Park’s municipal and provincial heritage landmark distinctions are important barriers standing in the way of impacting urban growth/reconfiguration and corporate development expansion, the addition of Canadian National Historic Landmark Site distinction could well ensure a final measure for lasting preservation. Such a quest lies before federal consideration as this essay is written. Finally, if Lord Byron, the inimitable English poet, was on the mark when he asserted that “the best prophet of the future is the past,” then perhaps Labatt Park has before it a glorious future in its service to London and Canadian citizens,60 as well as to the annals of baseball history.

ROBERT K. BARNEY, an American citizen, has lived and worked in Canada at Western University for 50 years. Educated at the University of New Mexico, he received his PhD in 1968; in 2014 Western University awarded him a doctor of laws, honoris causa. Recently he has worked with City of London heritage officials on a proposal to federal authorities for Labatt Memorial Park to be awarded National Heritage Site distinction.

RILEY NOWOKOWSKI is a PhD Candidate at Western University in London, Ontario. He loves all types of sport but takes a particular interest in baseball history. His work largely has focused on sport during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Devin Lindsay, Stephen Harding, and the entire London Room staff of the London Public Library.

Notes

1 We are indebted to Martin Lacoste for his penetrating compilations of baseball history’s earliest published record of games played in Ontario. Lacoste has documented that, by 1865, some 80 games had been played, most carried out under New York rules, between teams established in the Toronto/Hamilton/Woodstock/ London corridor. “Table of Baseball Games Played in Ontario, 1856-1865,” email Martin Lacoste to Robert K. Barney, July 27, 2020. A full list of these games through 1870 is available at http://baseballresearch.ca/early-games/.

2 For a detailed examination of cricket play in London in the nineteenth century, and its jousts with baseball for public following and playing space, see Tony Joyce, “At Close of Play: The Evolution of Cricket in London, Ontario, 1836-1902,” unpublished master’s thesis, University of Western Ontario, 1988.

3 See “Ready,” London Advertiser, March 31, 1877.

4 “The Ball Field,” London Advertiser, April 16, 1877.

5 Charles B. Chapman, born Charles Trollope in Norfolk, England in 1827, emigrated to the New World in 1848, settling eventually in New York City, where he earned a living in the bookbinding business and dabbled in drawing and watercolors, an artistic bent he demonstrated in his elementary-school years in England. In New York he married a French-Canadian woman. Hearing that a town in “Canada West” offered a “good opportunity for a bookbinder,” the couple left New York in 1855, crossed into Canada, and settled in London, Ontario. There, at the urging of his wife, he discarded the name Trollope, with its crude French connotation, and adopted the surname of Chapman, the maiden name of his wife’s mother. Between 1855 and 1875 Charles Chapman graduated from being an amateur artist to one of noted professional qualification. His watercolors and oils, mostly of landscapes, won prizes at various competitions, fairs and exhibitions. An excellent example of his work was his classic 1875 oil painting of the “Forks of the Thames,” displaying as it did the future site of Tecumseh/Labatt Park. For Chapman’s place in Canadian art history, see Nancy Geddes Poole, The Art of London: 1830-1880 (eBook Published by Nancy Geddes Poole, 2017), 25-26.

6 “The Ball Field,” London Advertiser, April 20, 1877.

7 “Out-Door Sports,” London Advertiser, April 23, 1877. The Atlantics, though a team composed of amateur players, were a formidable aggregation. By 1877 they deserved the distinction of being known as one of the top amateur baseball teams in the entire Dominion.

8 “Base Ball,” London Advertiser, April 24, 1877. The Hartfords, a seasoned professional team from Brooklyn, New York, were not members of the International Association. Known as the Dark Blues of Hartford, Connecticut, they had been an original member of the National League in 1876, moving at season’s end to Brooklyn for the National League’s second season in 1877. They visited London after playing games in Chicago and Detroit.

9 “Summer Pastimes,” London Advertiser, April 30, 1877.

10 “The Ball Field,” London Advertiser, May 4, 1877. Brackets ours.

11 See “The Ball Field,” London Advertiser, May 7, 1877.

12 See “The Ball Field,” London Advertiser, May 8, 1877.

13 See “The Ball Field,” London Advertiser, May 12, 1877 and May 14, 1877. See also Brian Martin, The Tecumsehs of the International Association: Canada’s First Major League Baseball Champions (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2015), 29.

14 “The Ball field,” London Advertiser, May16, 1877.The reference to “Maple Leafs from Guelph” refers to players and officials of the Guelph Maple Leaf Baseball Club, the London Tecumsehs’ chief Canadian baseball rival, as well as a fellow member of the new International Association.

15 The London Advertiser, established by John Cameron in October 1863, was an evening newspaper, in contrast to the morning London Free Press. The Advertiser, an almost immediate success, proved an able competitor to the Free Press, right up to its eventual demise in the fall of 1936. It was born in the midst of the American Civil War, a landmark struggle between Union and Confederacy that captivated the attention of London citizens, particularly as hundreds and hundreds of fugitive Southern Negro slaves sought freedom in Canada, particularly in southwestern Ontario. See Fred Landon, Western Ontario and the American Frontier (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1967 – Carleton Edition, original publication 1941), 215.

16 The London Free Press, an extension of the London Canadian Free Press (1849-1852), was established in 1856.

17 Admittedly, the position of home plate within the park grounds did indeed change, it would seem on at least four occasions over time, to its present position (2021).

18 For the importance of the safety bicycle in London, Ontario, see in particular Robert S. Kossuth and Kevin Wamsley, “Cycles of Manhood: Pedaling Respectability in Ontario’s Forest City,” Sport History Review, Vol. 34, No. 2, 170. For more, see Glen Norcliffe, The Ride to Modernity: The Bicycle in Canada, 1869-1900 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001). Here, Norcliffe argues that “the bicycle carrier wave formed a small part of an even larger cultural movement in Canada known as modernity” (31). Further, in his “National Identity, Club Citizenship, and the Formation of the Canadian Wheelman’s Association,” Journal of Canadian Studies, Vol. 51, No. 2 (January 2018), Norcliffe argues that the Canadian Wheelman, an early magazine published in southwestern Ontario, played a major role in the growth of the late nineteenth century Canadian bicycle craze (468). See also, Nancy Bouchier, For the Love of the Game: Amateur Sports in Small-Town Ontario, 1838-1895 (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003).

19 “Sporting,” London Advertiser, April 11, 1883.

20 For more on this elaborate facility, see Wheelman issues of December 1883 (Vol. 1, No. 4) and November 1883 (Vol. 1, No. 3).

21 The term “national sport” associated with lacrosse dates to an 1867 attempt by the Montréal dentist William George Beers to persuade Parliament in Ottawa to legislate the sport as Canada’s official “national game.” His attempt failed, but many in Canada, oblivious to Beers’ failure, then and now, think that lacrosse is Canada’s de facto national game. Beers himself was a noted lacrosse player in Montréal in the 1850s and 1860s. Further, he published the first standardized rules for lacrosse in 1860, was instrumental in expanding the number of lacrosse clubs in Ontario and Quebec in the decade following, formulated the National Lacrosse Association and its first annual convention, and helped organize the first international lacrosse tours to England in the 1870s. For this and more, he enters the annals of Canadian sport history as the “Father of Lacrosse.” For more, see Donald M. Fisher, Lacrosse: A History of the Game (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

22 “Sporting,” London Advertiser, April 11, 1883.

23 “Sporting,” London Advertiser, April 11, 1883. Brackets ours.

24 “Sporting,” London Advertiser, April 28, 1883.

25 “Sporting,” London Advertiser, May 3, 1883.

26 “Sporting,” London Advertiser, May 12, 1883.

27 “Sporting,” London Advertiser, May 14, 1883.

28 “Sporting,” London Advertiser, May 25, 1883.

29 “Sporting,” London Advertiser, April 6, 1883. Brackets ours.

30 “The Latest,” London Advertiser, July 11, 1883. A prolonged subheadline told the tale: “Terrible Destruction by Water- London West and Low Points of the City Submerged – Immense Loss of Life Feared – Moving Tales of the Flood – The Damage to Property Incalculable.”

31 “The Latest,” London Advertiser, July 11, 1883.

32 “Sporting,” London Advertiser, July 18, 1883. The July 1883 flood proved a disaster for the sport of lacrosse in London, especially lacrosse activity in Tecumseh Park. Shorn of its sticks, balls, and other equipment, which were carried away in the flood, the Lacrosse Club saw its membership dwindle, especially in the face of ever-increasing interest in cycling and baseball. In early August 1883, the London Lacrosse Club, now referred to as “The City Club,” made a “last moment” arrangement for a game against London East, to be played on the Queen’s Park grounds. The City Club “failed to muster a full team and were in consequence obliged to call upon London East for an additional supply.” See “Sporting,” London Advertiser, August 3, 1883. We could not find a record of lacrosse activity in Tecumseh Park after the 1883 flood.

33 “London West,” London Advertiser, November 2, 1883.

34 “London West,” London Advertiser, November 7, 1883.

35 “City Is Given Tecumseh Park, $10,000,” London Free Press, December 15, 1936.

36 The logic here being that far fewer “sun affected” plays by outfielders occurred in comparison with “each pitch” experienced by batters in the course of the game.

37 We originally became interested in the orientation of a bicycle track in Tecumseh Park introduced in 1895 due to a reference made to us by Stephen Harding, for which we are grateful. Furthermore, there is a notation regarding the bicycle track in Daniel Brock’s Fragments from the Forks: London, Ontario’s Legacy (London, Ontario: London and Middlesex Historical Society, 2011), 147.

38 “The Green Diamond,” London Advertiser, May 20, 1895.

39 “It is a Go,” London Advertiser, May 25, 1895.

40 Discussions on building a bicycle racing track occurred as early as 1894, as noted in the Canadian Wheelman Magazine. For example: “The Meteor club has a membership now of about 70, and we are receiving applications for every meeting. We are growing fast, and, ‘to put a flea in your readers’ ears,’ it is our intention to make a strong bid for the C.W.A. meeting of 1895. By that time we expect to have one of the best athletic grounds in the Dominion, including an up-to-date bicycle track. We are in the swim to stay.” “London Meteors,” The Canadian Wheelman, August 6, 1894.

41 “It is a Go,” London Advertiser, May 25, 1895.

42 “Work Begun,” London Advertiser, May 27, 1895: “… The track has been staked out. The home stretch is to be west of the baseball diamond and 30 feet wide. The course will gradually narrow, until on the east side, or near the breakwater, it will only measure 16 feet….”

43 See, for instance, daily copies of the London Advertiser, May 25 to August 16, 1895.

44 For an enlarged description of the entire grand opening, see “Wheelmen Happy,” London Advertiser, August 19, 1895.

45 “Wheelmen Happy.”

46 “Wheelmen Happy.”

47 “The Diamond Meet,” London Advertiser, August 29, 1895.

48 For more on this, see Robert K. Barney, Mustangs 100: A Century of Western Athletics (Straffordville, Ontario: Sportswood Printing, 2013), 12, 17.

49“City Is Given Tecumseh Park, $10,000: Famous Playground Donated by Labatt Family to Citizens,” London Free Press, December 15, 1936.

50 London Free Press, January 14, 1937: “Last night streets ran deep with water and small floods were reported at one or two city parks.”

51 London Free Press, February 9, 1937: “Old Man River went on a rampage in London following heavy rains….”

52 London Free Press, April 26, 1937: “Scores of homes were menaced, streets were submerged, at least four district bridges were closed to traffic….”

53 London Free Press, April 27, 1937: “… mounting menace of disease, one man drowned, 6,000 without homes, South London completely isolated to motor traffic.”

54 “Labatt Park Is a Young Lake,” London Free Press, April 28, 1937.

55 “Labatt Park in Bad Condition,” London Free Press, April 6, 1937.

56 Howard Broughton, “On the Sport Trail with Howard Broughton,” London Free Press, May 14, 1937.

57 For a full treatment of this phenomenon and Labatt Park’s role in the development, see Carly Adams, “Communities of Their Own: Women’s Sport and Recreation in London, Ontario, 1920-1951,” unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Western Ontario, 2007.

58 Better known, but similar circumstances, are associated with many original historic sporting precincts, for instance, the Kentucky Derby and Churchill Downs in Louisville, Kentucky; the Boston Red Sox and Fenway Park in Boston, Massachusetts; and the Indy 500 and the Indianapolis Speedway in Indianapolis, Indiana.

59 Co-author Dr. Bob Barney was present at those proceedings, and in fact rendered the keynote commemorative address.

60 Lord George Gordon Byron’s notable quotation appeared in a letter written by him on January 28, 1821, composed in Greece, the country of his residence for the last three decades of his life. For the letter’s transcription, see: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16609/16609-h/16609-h.htm.