A Dark, Rainy Game Seven: The Pirates Defeat the Big Train in the 1925 World Series

This article was written by Gary Sarnoff

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot tosses the ceremonial first ball prior to a World Series game in 1925. (COURTESY OF THE PITTSBURGH PIRATES)

“It was a great day for water polo,” quipped New York Times sportswriter James R. Harrison.1 On Thursday, October 15, the Pittsburgh Pirates and Washington Nationals met in horrific weather conditions to play Game Seven of the 1925 World Series. And when Game Seven had concluded, it was considered “the wettest, weirdest and wildest game ever seen.”2 It was also described as one of the most exiting games ever witnessed. “No World Series has ever come to the sensational climax which marked the feverish finish of today’s game,” wrote sportswriter Harry Cross, also of the Times.3

During a rainy, foggy, and dark morning on game day, doubt was cast over the seventh game. The decision to play or not fell to the Judge and only he. “From his first world series in 1921, Landis took complete charge of the annual baseball classic,” wrote Sporting News editor Taylor Spink.4 Shortly after noon, as Landis walked along the waterlogged Forbes Field surface, he noted the mud puddles in the outfield and the quagmire that comprised the infield and pitcher’s mound. Landis admitted that the conditions were poor, but declared that the show would go on. Word spread quickly throughout Pittsburgh, and by game time, over 42,000 packed Forbes Field.

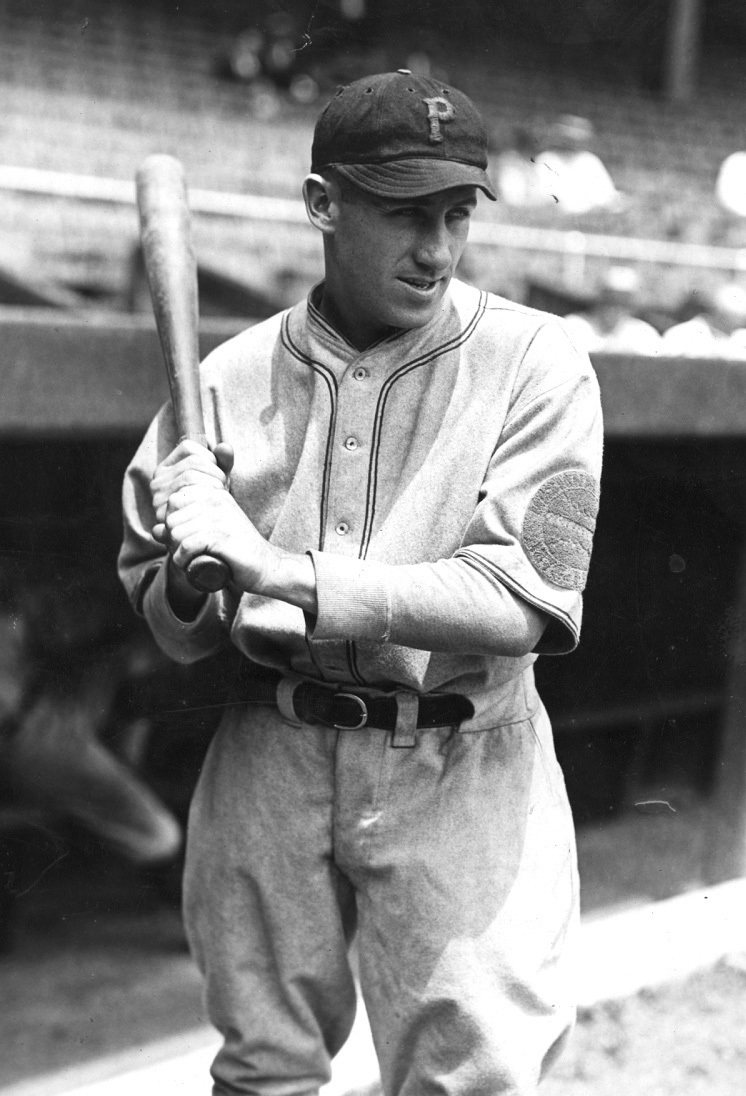

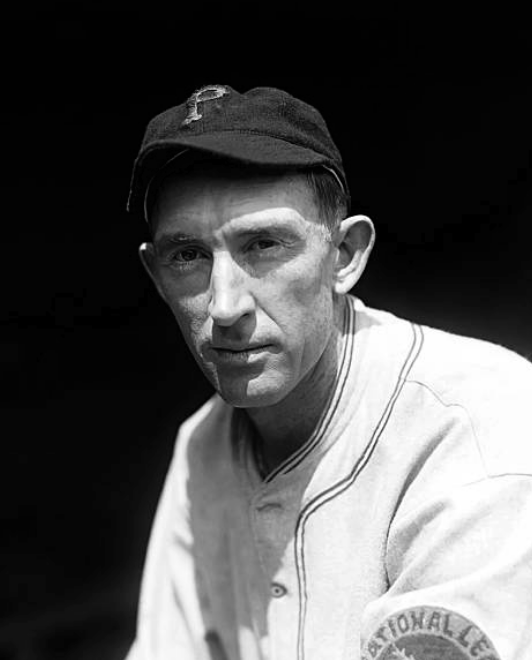

Could the Pirates win? If they did, they would make history, for no team in a best-of-seven World Series had ever come back from a 3–1 deficit in games to win. And winning would not be easy since the Pirates would have to face the Big Train, Walter Johnson, who had already defeated the National League champs twice in this series. Pirates manager Bill McKechnie believed his team could do it, especially because his Game Seven starting pitcher, Vic Aldridge, had two wins over Washington. “The Senators fear Aldridge as much as we fear Johnson,” said the Pirates manager.5

The Forbes Field crowd gave Aldridge an ovation when he took the mound. One local writer insisted that he had “plenty of stuff” during his warm-up session, but it was a different story at game time.6 After giving up a leadoff single and recording one out, Aldridge walked three in a row to force home a run. An additional single led to his departure, and two more Pittsburgh miscues resulted in a 4–0 Washington lead. The crowd, doubting a four-run lead could be overcome against Johnson, began to call upon Jupiter Pluvius to act. A postponement seemed to be their only hope.

Johnson struck out two while retiring the Pirates in order in the bottom of the first. The Pirates also failed to score in their second at-bat, but in the third inning, they finally broke through. “After the Pirates scored their first run, the crowd began to howl,” wrote Cross. “They howled and screamed and forgot about the darkness and rain. They were cold and damp, but it was all forgotten in the raucous paeans of joy which echoed over the rolling hills of Oakland.”7 Two more runs were added in the inning to cut the Washington lead to 4–3.

The rain fell harder, the skies grew darker, and the ball became more difficult to see in the top of the fourth, causing a buzz among the crowd that the game would be called, but one writer noted, “The darkness didn’t seem to worry [Goose] Goslin or Joe [‘Moon’] Harris, for Goose singled and ‘Moon’ brought Goose home with a [two-run] double” to extend the Washington lead to 6–3.8 In the bottom of the fifth, Max Carey and Kiki Cuyler hit back-to-back doubles to score one for the Pirates and cut the lead to 6-4. Then Johnson “tightened up like a vice” and retired the next three batters to end the inning.9 With five innings now in the books, Landis, seated next to the Washington dugout, decided that this was an official game. He turned to Nationals owner Clark Griffith and told him, “You’re the world champions. I’m calling this game.”

“Once you started in the rain you’ve got to finish it,” replied Griffith, and the game continued.10

By the seventh inning, the steady rain became a downpour. The skies grew even darker and visibility became worse. With the Pirates still trailing 6–4, the fans stood and cheered during the seventh-inning stretch and remained standing when Eddie Moore came to the plate to lead off the Pirates’ seventh. The second baseman hit a routine pop fly that Senators shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh camped under. “It was the kind of ball Peckinpaugh had caught 999 out of 1,000 times,” wrote Hugh Fullerton. “This time he let it slip through his fingers.”11 Moore made it all the way to second base on the misplay. Carey followed with a fly ball down the left field line. Washington left fielder Goslin drifted far to his right. He got his hands on the ball but was unable to hold it. Moore scored and Carey went all the way to second base. The Nats immediately protested, claiming the drive to be foul. Bucky Harris, the Washington manager and second baseman, raced from his position to third-base umpire Brick Owens.

Harris: “Mr. Owens, what did you call that ball?”

Owens: “What did (home plate umpire) McCormick say?”

Harris: “He said it was a fair ball.”

Owens: “Then that’s what I saw.”

A voice was then heard from left field: “Come on down, one of you umpires, and see where this ball was hit.”12 The umpires declined the invitation, the call stood and the game continued. Johnson retired the next two, but then Pirates third baseman Pie Traynor got hold of one. “The ball jarred off his bat so fast that nobody saw it,” wrote Cross. The drive sailed to right-center field, then disappeared. Carey easily scored to tie the game 7–7. Washington outfielders Sam Rice and Moon Harris, running in pursuit of the hit, vanished in the darkness.

A voice was then heard from left field: “Come on down, one of you umpires, and see where this ball was hit.”12 The umpires declined the invitation, the call stood and the game continued. Johnson retired the next two, but then Pirates third baseman Pie Traynor got hold of one. “The ball jarred off his bat so fast that nobody saw it,” wrote Cross. The drive sailed to right-center field, then disappeared. Carey easily scored to tie the game 7–7. Washington outfielders Sam Rice and Moon Harris, running in pursuit of the hit, vanished in the darkness.

“The expectant crowd was on its feet cheering every stride Pie took in his mud circuit,” was how Cross described the action. “The mud splashed from his spiked shoes as he rounded second and tore toward third.”13 Bucky Harris, taking Moon Harris’s throw, wheeled and threw home in plenty of time to head off Traynor, who didn’t even slide on the play.

The water dripped from the bill of Peckinpaugh’s cap as he came to the plate with one out and nobody on base in the top of the eighth. “Peckinpaugh was shaking with emotion,” wrote Fullerton.14 Poor Peckinpaugh, who had been selected by the sportswriters as the 1925 American League MVP a month earlier, was struggling in this World Series. His error that helped the Pirates tie the game in the prior inning was his seventh, tying the World Series record. “If there ever was a stage set for a hero, that scene grabbed Peckinpaugh as he came up in the eighth,” wrote Pittsburgh sportswriter Regis M. Welsh. Pirates pitcher Ray Kremer made his pitch; Peckinpaugh gritted his teeth and grunted when he swung, and he connected. The fans watched the ball fly into the outfield and followed it until it disappeared in the dark. Left fielder Clyde Barnhart turned and ran toward the fence. Nobody knew what had happened until a fan’s loud voice rang out for all to hear: “It’s a home run.”15 Washington was now back in the lead, 8–7.

The Washington bench went wild. From World Series goat to World Series hero, Peckinpaugh wept tears of joy as he made the circuit. Several Pittsburgh fans, stunned by what they just saw, stared into space with an expression of disbelief across their features. Others headed to the exits. “None would now question Peckinpaugh’s right to the valuable player prize. He proved it,” wrote Welsh.16 Washington’s shortstop was welcomed in opened arms when he reached the dugout. His teammates patted him on the back. Some hugged him. A few kissed him. “The run scored loomed as the last defense against a game club,” Welsh noted.17 With six outs to go and Walter Johnson pitching, the lead seemed safe.

“There’s only two out,” Pirates catcher Earl Smith said to himself as he strode to the plate in the bottom of the eighth.18 Johnson had retired the inning’s first two batters and appeared confident of victory. He threw with confidence to Smith, but the Pirates catcher connected on one and drove it into right-center field for a double.

Two outs, a runner on second and the pitcher due up. McKechnie responded by sending a pinch-hitter to the plate. His choice, Carson Bigbee, whose regular season batting average was .238, was a disappointment to the hometown fans. “Everybody started to groan and question the judgment of the Pirates boss,” wrote the legendary Honus Wagner, who was covering the series for a Pittsburgh newspaper.19 “Carson hasn’t hit the size of his hat. No one had faith in him but McKechnie.”20

Bigbee came through with a solid hit over Goslin to score Smith with the tying run. Certain that Johnson was wearing down, the small gathering of Senators fans behind the Washington dugout began to call on Bucky Harris to replace Johnson, but the Washington manager was determined to stick with his best pitcher. The Washington fans made more noise when Moore, who had hit the wayward popup in the seventh, walked to put runners on first and second. “Johnson was tired,” a writer insisted. “He tried to put the ball over for Eddie Moore, but couldn’t make it.”21

The next batter, Carey, grounded directly to Peckinpaugh, who was unable to handle the wet ball. He then reached for the ball, but it slipped out of his hands. Now too late to get the speedy Carey heading to first, the Washington shortstop threw to second base but his throw was too high. Bucky Harris, covering second on the play, leaped into the air and came down too late to force the runner. Peckinpaugh was charged with another error, his eighth of the World Series, to set a record.

Up came Kiki Cuyler with the bases loaded and two outs. Johnson got ahead in the count with a ball and two strikes. The great hurler then went into a long windup. Thinking he was about to see Johnson’s fastest pitch, Cuyler inched to his right. Johnson made his delivery, a curveball that fooled Cuyler to the point where he took the pitch. The crowd let out a loud groan when the ball split the heart of the plate. Ruel took off his mask and Johnson walked off the mound, thinking the inning was over. Then the crowd’s groans turned to cheers when home-plate umpire Barry McCormick called ball two.

Up came Kiki Cuyler with the bases loaded and two outs. Johnson got ahead in the count with a ball and two strikes. The great hurler then went into a long windup. Thinking he was about to see Johnson’s fastest pitch, Cuyler inched to his right. Johnson made his delivery, a curveball that fooled Cuyler to the point where he took the pitch. The crowd let out a loud groan when the ball split the heart of the plate. Ruel took off his mask and Johnson walked off the mound, thinking the inning was over. Then the crowd’s groans turned to cheers when home-plate umpire Barry McCormick called ball two.

Cuyler stepped back into the box. Johnson pitched, Cuyler swung, and—“Whack,” wrote the Pittsburgh Press—drove the ball down the right-field line.22 The ball fell into fair territory, then rolled into foul territory, into the bullpen, and under the tarp. All three runners scored and Cuyler rounded the bases. The umpires, however, ruled the hit a ground-rule double, meaning that Cuyler would have to return to second and Carey was sent back to third base. Two runs did count to give the Pirates a 9–7 lead.

The Nats had one last chance in the top of the ninth. McKechnie, with one more trick up his sleeve, sent in Red Oldham, a former American League pitcher who had been signed by the Pirates in midseason. Oldham’s best value was that he had defeated the Nationals seven times in 1922, and he came through by retiring the Senators in order. The Pirates had done it. They were world champions.

GARY A. SARNOFF has been an active SABR member since 1994. A member of the Bob Davids and Goose Goslin SABR chapters, he has also contributed to SABR’s Bio and Games Projects, to the annual National Pastime publication, is a member of the SABR Negro Leagues committee, and is the chairman of the Ron Gabriel Award committee. In addition, he has authored two baseball books: “The Wrecking Crew of ’33” and “The First Yankees Dynasty.” He currently resides in Alexandria, Virginia.

Notes

1 James R. Harrison, “Pirates Victory Caps Weirdest of Games,” New York Times, October 16, 1925.

2 Harrison.

3 Harrison.

4 J.G. Taylor Spink, Judge Landis and Twenty-Five Years of Baseball (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1947), 101.

5 Denman Thompson, “Drizzle May Stop Final Game Again; Field a Quagmire,” Washington Star, October 16, 1925.

6 Regis M. Welsh, “Greatest Drama in History of Sport Enacted as Bucs Rout Senators From Throne,” Pittsburgh Post, October 16, 1925.

7 Harry Cross, “Pirates Are Now World Champions; Win Last Game, 9-7,” New York Times, October 16, 1925.

8 Frank H. Young, “Nationals Drop Deciding Game to Pirates,” Washington Post, October 16, 1925.

9 Cross, “Pirates Are Now World Champions.”

10 Hank W. Thomas, Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 282.

11 Hugh Fullerton, “Pirates Batter Lame Johnson to Cop, 9-7,” Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1925.

12 Frank T. Sullivan, “Series Umpiring Was Nothing to Sing Songs About,” Washington Herald, October 17, 1925.

13 Cross, “Pirates Are Now World Champions.”

14 Fullerton, “Pirates Batter Lame Johnson.”

15 Welsh, “Greatest Drama in History of Sport.”

16 Welsh.

17 Welsh.

18 Welsh.

19 Honus Wagner, “Pittsburgh Speed Was Too Much for Senators,” Pittsburgh Press, October 16, 1925.

20 Welsh, “Greatest Drama in History of Sport.”

21 Ralph Davis, “Sports Chat,” Pittsburgh Press, October 16, 1925.

22 Davis.