‘A Foremost Part in the Work of Relieving Distress’: When the Giants and Yankees Offered a Lifeline to the Titanic’s Survivors

This article was written by Dan VanDeMortel

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

Like 9/11, the sinking of the Titanic clings to American memory, slicing across sex, race, age, geographical, and class divides. Generations later, mental snapshots of the disaster develop at the briefest mention. An iceberg on a moonless night. The Law of the Sea: women and children first. The fortunate watching from insufficient lifeboats while others die in frigid Atlantic water.

What city was most traumatized by Titanic’s demise? Most would select its Belfast birthplace, perhaps European ports of call. Not so. New York was the catharsis epicenter, and the place baseball played an unexpected role in alleviating suffering.

The period from 1900 to World War I’s commencement is sometimes labeled “The Quiet Years.” World conflicts were few. Economic prosperity reigned. By 1912, post-diet, 270-pound President William Taft was facing a formidable election against Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. A Quiet Leader, he had left scant legislative impression but had tossed the first Presidential Opening Day pitch, chewed peanuts with common folks at others, and pronounced, “Any man who would choose a day’s work over a day of baseball is a fool not worthy of friendship.”1

Taft’s bonhomie, however, contrasted with his nation, which was hardly quiet. Instead, America was beset with hectic change and unrelenting new technology. Henry Ford’s mass-produced Model T was transforming isolated villages into a mobile, connected network. Cameras, movies, telephones, and telegraphs were accelerating communication. Farm life was giving way to urban employment at the mercy of industrial and financial corporations. The average person lived about 50 years, most of it spent working brutal hours, which was viewed as the key to success. Even children toiled at this rigorous schedule, and like their parents were provided scant economic protections. Women slogged along, too, at repetitive jobs and ritualized household chores.2 Some fought the slowly successful battle for suffrage. Progressivism—political faith that science and rationality could salve America’s condition —weighed in with incremental, mixed results.

No city embodied this hustle in 1912 more than New York. With its first skyscraper rising in 1889, Manhattan had commenced a construction boom previously unimaginable and unachievable, highlighted by the in-progress 792-foot Woolworth Building, slated to be the world’s tallest building. With its boroughs recently consolidated, the city had trebled in size and exploded to 5.2 million people, second to London. Residents travelled via the new subway as well as horse, cable car, or trolley. Pennsylvania Station and the main library had just been built, and Ebbets Field had broken ground in March. With 80% of the city’s inhabitants immigrants or their children, many viewed their fluctuating home as a foreign country. Immensity and innovation now characterized an “Imperial City,” blessed by America’s grandest mansions, shamed by its worst slums. Only Tammany Hall’s corrupt governing machine, like a cockroach, remained ubiquitous and constant.

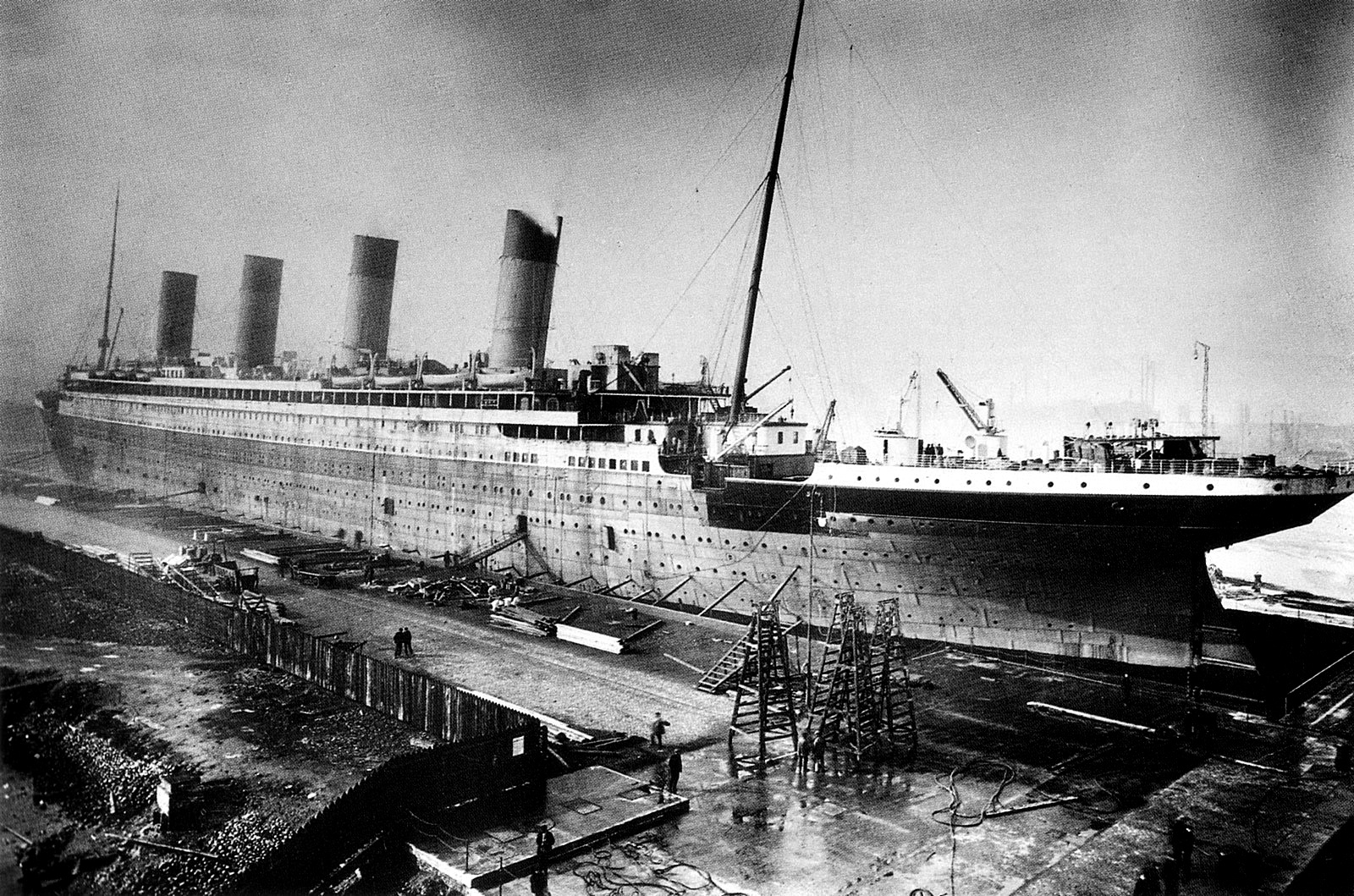

New York also hosted the world’s biggest ships. Appropriately, the city anticipated the Titanic’s maiden voyage. The Sunday, April 14 New York Times heralded the April 17 arrival of “The New Giantess,” marveling as we do at its 883-foot length and 94-foot width, the equivalent of an 11-story building laid end to end.3 Coverage extolled the opulent spas, services, lodging, and meals available to the age’s wealthy “1%.” Unexpressed was how these socialites crested atop of the technologically-unsurpassed ship’s “floating layer cake” while below, in a societal microcosm, one descended in class to the anonymous laborers fueling the ship deep in its boilers.4

Anticipation turned to dread when ominous reports surfaced regarding an iceberg encounter. Initial communication errors and journalistic speculation steered damage estimations into confusion and inaccuracy. One paper even proclaimed, “All Saved from Titanic after Collision.”5 The Times responded more cautiously, later revealing that developments, about 1,080 miles away, were far deadlier.6

As the grim news unfolded, New York entered post-9/11-like hellish days of waiting and wondering. Highly imaginative conjectures, wavering fatality statistics, embellished tales of heroism and cowardice, and cold facts dominated public encounters. Some even questioned “The Law of the Sea,” arguing Chinese hierarchy should have been followed by valuing women last.7 Meanwhile, citywide half-mast flags and news coverage of ships searching for bodies confirmed undebatable fatalities. Crowds up to 50,000 people huddled on streets at the ship’s White Star Lines Broadway office or at newspaper buildings, waiting for publicly-displayed bulletins regarding survivors. Smaller groups clustered at hotels, stores, and other buildings. “Conversations, sometimes half hysterical, sometimes filled with sobbing, were heard on every side,” the Times reported, even amongst those unconnected to anyone on board.8

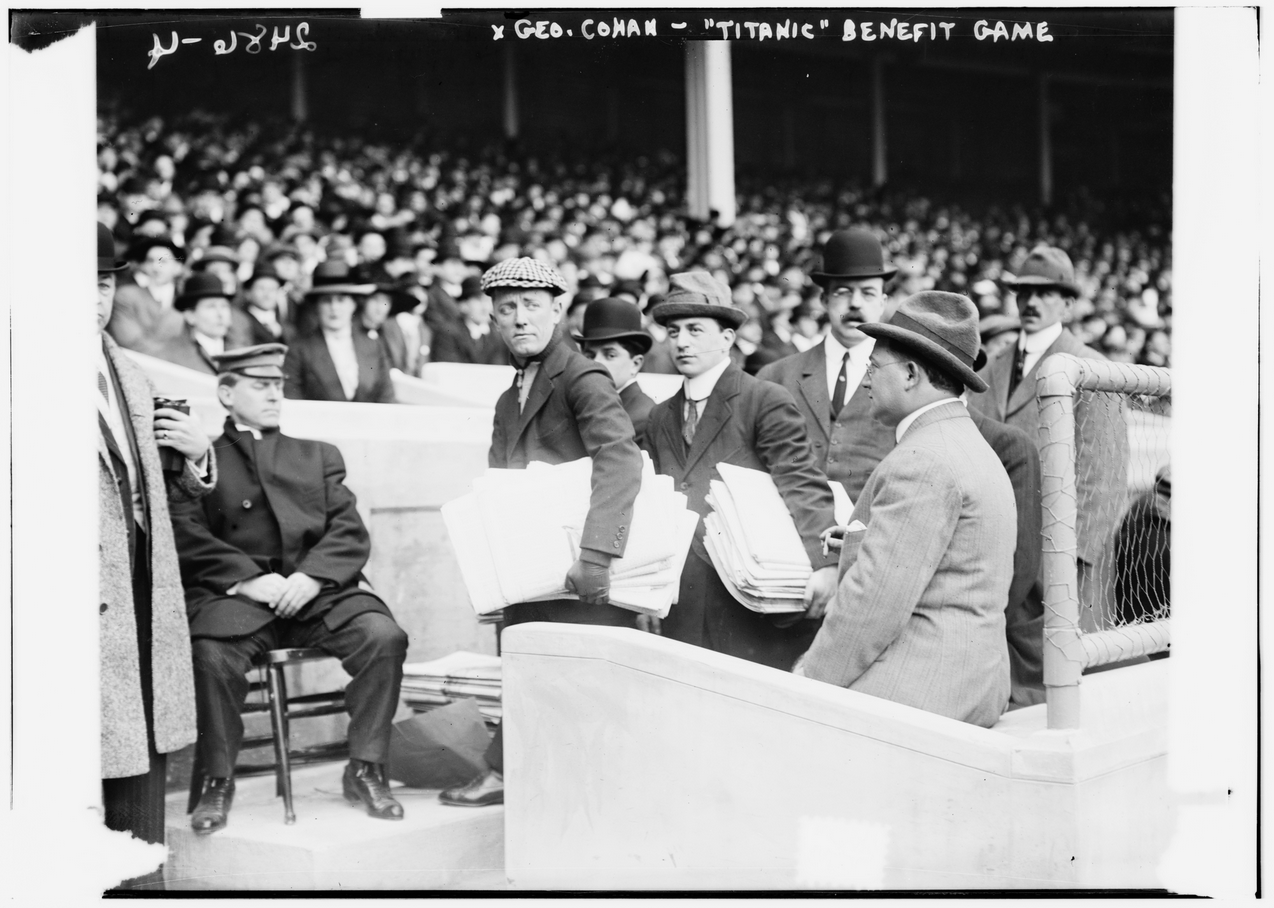

Broadway icon George M. Cohan, a Polo Grounds habitue and friend of Giants manager John McGraw, in the process of selling copies of the New York American to benefit the Titanic’s survivors on Sunday, April 21, 1912, at the Polo Grounds. Assisting right behind him is Jack Sullivan, founder of the Newsboys’ Home, an organization with connections to assorted nefarious, nocturnal activities. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, BAIN COLLECTION)

President Taft cancelled his Opening Day appearance in Washington upon learning a close military aide had perished. But even the President was eclipsed by New York, which became the primary setting of suspense and resolution as the week dragged on. On a rainy Thursday evening, the rescue ship Carpathia passed 10,000 onlookers at the Statute of Liberty before docking at Manhattan’s pier 54 with its cargo of 712 Titanic survivors. Amidst heavy security, 30,000 people, 50 ambulances, and numerous relief workers and customs officials waited for the saved. As they disembarked, “a low wailing sound started from the crowd. Its cadences, wild and weird, grew steadily louder and louder until they culminated in a mighty shriek,” that swept the pier as if guided by “some master hand.”9 Next morning brought legal and political drama as a Senate inquiry into the sinking commenced at the Waldorf-Astoria.10 Testimony pinpointed root causes already surmised by the Washington Post: “Speed, madness, and a reckless disregard for human life in the scramble for business.”11

For many reasons, concern for the survivors abounded in New York more than anywhere in America. In a city that embraced size and technology, interest and suspense was already feverish. Titanic’s over 1,500 victims proved extremely personal, too: 11 city natives, 76 residents, and 146 people travelling to New York were on board; 129 died.12 Among them included such notables as Waldorf-Astoria builder John Jacob Astor and Macy’s co-owner Isidor Straus. New Yorkers could also easily relate to Titanic passengers seeking adventure or fresh opportunity. And most everyone recalled the 1904 General Slocum disaster, when a steamer filled with German-American families from the Lower East Side caught fire on the East River, killing 1,021 in the city’s worst pre-9/11 tragedy.

This empathy translated into action on many fronts. Mayor William Gaynor opened a relief fund that procured over $130,000 from socialites, companies, religious organizations, and average citizens. Prominent women organized another fund, raising almost $36,200. Newspapers, too, called for currency, including William Randolph Hearst’s New York American, which collected $62,000. Hospitals contributed beds, medical professionals their time, and persons of modest means whatever they could.

Perhaps the most unexpected effort came from New York Giants owner John T. Brush who Friday night offered his Polo Grounds to New York Yankees owner Frank Farrell for a Sunday fund-raising exhibition game between their teams. To do so, however, he challenged two traditions. First, the teams had a tense relationship. A decade previously, Brush had fought to prevent the new American League from moving a club into New York, then in 1904 had dismissively refused to play the junior circuit in the World Series when the Yankees looked primed to be its representative. 1910 brought a thaw and at season’s-end, a best-of-seven series, won by the Giants four games to two. (Each Giant’s winning share of $1,110.62 and Yankee’s losing share of $706.76 helped explain the “thaw.”13) A few more ice drops fell in April 1911 when Farrell, upon learning that a fire had destroyed the Polo Grounds, offered Brush shared usage of his Hilltop Park home, which the Giants quickly accepted to cover a three-month rebuilding process. But there had been no 1911 rematch.

Second were Sunday “blue laws.” Governing protections for Sabbath rest had arrived from England in the seventeenth century, when behavior ordinances were printed on blue paper. The laws weren’t always popular, yet they stuck. The National League ruled in 1876 against Sunday play, later retreating to allow games, as would the American League, upon local approval, which proved inconsistent and infrequent. By 1912, prohibitions against Sunday games were still in effect in New York and would remain so until the 1919 season.

Undeterred, Farrell quickly agreed to Brush’s proposal, both owners scuttling animosity to express written gratitude that baseball would take “a foremost part in the work of relieving distress.”14 No words explained blue law workaround negotiations, but possibly Farrell offered Brush a slice of instructive personal history. In 1906, he had hosted a Sunday game versus the Philadelphia Athletics, with no objections, to raise San Francisco earthquake relief.15 And in 1909, the Brooklyn Superbas had welcomed his team in a charity-driven Sunday match. With these likely precedents, both owners agreed to play Sunday, April 21 — a first for the Polo Grounds, and the first in-season interleague game since the American League’s formation.16 Program sales would substitute for admission, all proceeds directed toward survivors.

From a public relations standpoint, Farrell was in no position to decline Brush, nor was his team. Despite wearing their April 11-debuted pinstripes, the Yankees bore little resemblance to their modern, dominant counterparts. The team known in the press by numerous nicknames—including Americans, Invaders, Hilltoppers, Highlanders, and Yankees until officially adopting the last the following year—played second fiddle to the Giants. 17 Farrell’s club was consistently outdrawn by a heavy ratio, and habitual second-division finishes gave fans good reason to stay away. A 1911 .500 mark conveyed slight optimism, but spring training rains in Georgia had limited practice to a mere three days, paving a 0-6 start.18

The Giants were everything the Yankees were not. Brush’s public frailty due to debilitating locomotor ataxia was the club’s only infirmity.19 Regular first-division finishes, league-leading attendance, a 1905 World Series, and appearances in 1911 and 1912 testified to vitality. The Giants reflected the smarts and will of manager John McGraw, a man of amazing contradictions. Off the field, he frequented race tracks, pool halls, fancy restaurants, and vaudeville, and was regarded for his soft-touch generosity. On the field, he was known as “Little Napoleon” and his “great heart contract[ed] to the dimensions of a bean.”20 Supported by pitching legends Christy Mathewson and Rube Marquard, he personified the Deadball Era and hurled invective that “would have to be written on asbestos paper.”21 His team had swiped a post-19th century high 347 steals the previous year, would pilfer 319 in 1912, and had a champion’s swagger.

The Giants would bring another advantage: Charles “Victory” Faust. Mascots in 1912 mirrored industrial overlords’ relationship to its workers: top-down and exploitive. “Colored boys,” dwarves, hunchbacks, and “retarded” adults filled these roles, providing amusing good luck charms in a sport rife with superstition. The slow-witted, gap-toothed, eccentric 31-year-old Faust, from rural Kansas, fit right in. He had materialized the previous year, claiming a fortune teller had predicted a Giants championship if he were allowed to pitch. A windmill motion and soft tosses revealed little skill, but he became an all-star butt of practical jokes and purveyor of pre-game comedy—some intentional, some not. The team was 36-2 when he was in uniform, showcasing his act.22 Fans and newspapers devoured this burlesque. He was even allowed to pitch in two meaningless season-ending games, sporting a 4.50 ERA while being hit by a pitch and allowed to steal twice in a plate appearance. A World Series loss, however, burst the bubble. By 1912, McGraw had tired of Faust, refusing to let him “sign” with the team or don a uniform. But for the charity game, announcements signaled his resurrection.

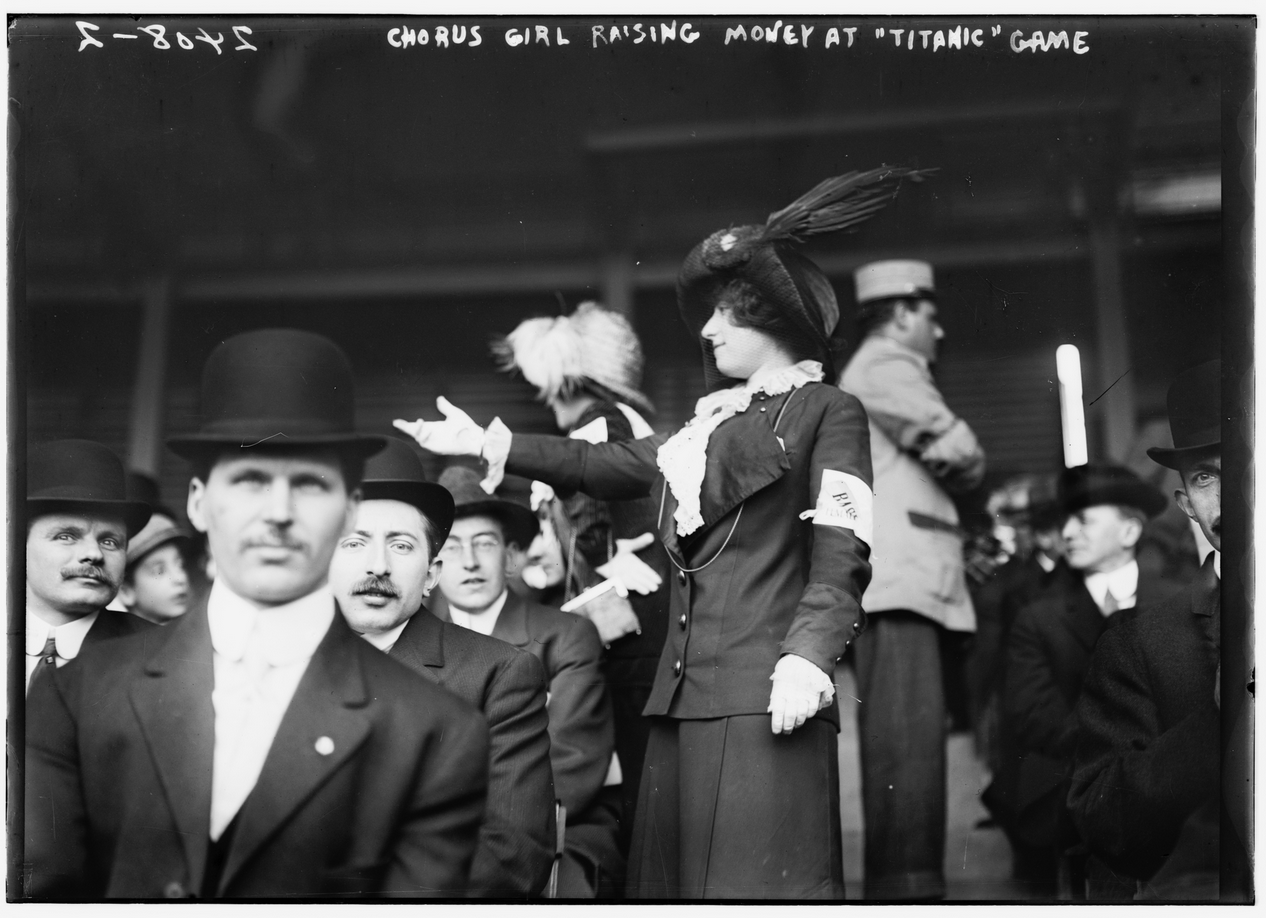

At the Titanic benefit exhibition game on April 21, 1912, two members of the Female Giants — a women’s baseball team with connections to the New York Giants — roam the aisles to request donations to assist the ship’s survivors. A Polo Grounds employee, in hat and jacket, is in the background. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, BAIN COLLECTION)

Sunday afternoon delivered welcoming sunshine and moderate southern winds over Coogan’s Bluff, then a virtual countryside from which residents could view part of the playing field below. As the gates opened a “wild clatter of howls” erupted as fans purchased programs entitling them to unreserved seating.23 Brush arrived by limousine and sat in left center. Farrell attended, as did other Giants and Yankees employees, who assisted with the crowd: rich, poor, Tammany Hall cogs, Wall Streeters, and Broadway aficionados.

And what a horseshoe-shaped park to be in! Concrete-and-steel with detailed, captivating architectural flourishes had replaced the wooden firetrap. A clover-shaped infield even featured ornamental circles built into the dirt. Baseball Magazine described the 34,000-seat “beauty” as rivaling the “silent grandeur” of the Pyramids.24

To ensure victory—and laughs—Faust took center stage in a discarded 1911 World Series uniform, pitching left-handed and running bases to the crowd’s delight. Also on hand was McGraw pal and park habitué vaudeville icon George M. Cohan, “the man who owned Broadway,” the entertainment capital of America. Covering the city on an aid-seeking mission, he roamed the stands in sweater and slanted cap, soliciting relief and selling New York American newspapers on the survivors’ behalf. Assisting him was a far murkier character: Jack Sullivan, founder of the Newsboy’s Home. Outwardly, this “Home” was an athletic/meeting place for boys who hawked newspapers on street corners. On a primal level, the hard-scrabble club was linked to prostitution, the Mafia, and other nefarious, nocturnal activities.25 Months later Sullivan would be indicted in the murder of bookmaker Herman Rosenthal, whom he possibly collected for, a crime memorialized in The Great Gatsby.26

With flags at half-mast, World Series-like rituals were enacted. As the teams entered— Yankees outfitted in road grey, Giants in home white with pinstripes—they were greeted by loud cheers. Both managers received a warm reception as they shook hands at home plate. Soon thereafter, veteran chief umpire Cy Rigler and second-year base umpire Bill Finneran appeared. Each had been vilified for controversial calls in the preceding two days, but bygones were bygones now, and they were given a big hand as they volunteered their time. Movie men and photographers moved about, capturing the scene. Rigler neared home plate at three o’clock, barked out the starting batteries via megaphone, and the game was on.

Leaving their box seats, some Female Giants began working the crowd, requesting New York American-relief fund donations and storing their gatherings in caps borrowed from Giants players. Patronized as “featherweights” in one news account, they were anything but. Rather, these Giants—led by Broadway celebrity, Hollywood actress, and “the best all-around athlete of America,” pitcher Ida Schnall—consisted of 32 young women athletes who played each other throughout the city, sometimes joined by the Giants.27 Clad in restrictive, layered clothing and ornately-plumaged “tray hats,” they accepted contributions from similarly-garbed female fans and men in dark suits, ties, and derby hats.

Due to injuries and illness—and Wolverton’s decision to sit many starters—the Yankees led off against seldom-used youngster Bert Maxwell with a lineup of scrubs. Smooth-fielding but notoriously corrupt first baseman Hal Chase, the lone infield regular, singled in a run for a promising start for the visitors.

Then the Giants batted. Pre-game reportage that Brooklyn would contribute players proved inaccurate, which was unfortunate: The Yankees needed help. McGraw fielded several front-line players, who came out electrically charged. Five runs were tallied off starter George McConnell’s spitball before an out was recorded. Two walks, four hits, sloppy fielding, and a blown “safe” call by Finneran authored quickly daunting math. And “McGraw ball” ran amok: Tillie Shafer and Fred Snodgrass swiped the first of two Giants double steals that afternoon, while Fred Merkle and Red Murray scampered for solo bags. 5-foot-10, 175-pound catcher Gus Fisher suffered a nightmarish inning, unsure where to throw next, once even wisely declining an attempt to nail a runner.

In the second, the Yankees scratched out another run and held the Giants scoreless for two frames. Then, in the fourth, slaughter returned. Whacks of Giants hits rang out while the Yankees assisted with a walk, a hit batter, three errors, and overall infield ineptitude. Five runners scored. After that, everything else was garbage time. McGraw inserted subs wholesale. His roster’s depths delivered the tongue-twisting Phifer Fullenwider, who allowed no runs in the highest-profile game of his career: He would never pitch in a regular season major league game.28

During the sixth, another exhibition briefly flared. Two men in front of the lower grand stand commenced fighting, “maul[ing] away regardless of Queensberry [rules]” until stopped by police.29 (Yankees fans surely welcomed the distraction.) In the stands, fans smoked cigars and cigarettes, and purchased pie slices and hot dogs—a recent Polo Grounds innovation—from coat-clad waiters. Sunday laws banished alcohol, outfield fence ads promoting it notwithstanding.

The contest concluded in two hours: an 11-2 Giants “bragging rights” pasting. Available box scores differ slightly but enumerate a grim Yankees afternoon: Eight innings of 12-13 hits, three-four walks, and a hit batter surrendered by McConnell; six-seven stolen bases allowed; and four-five errors recorded along with other unclassifiable folly30 In perspective, though, only these numbers mattered: 14,083 patrons, $9,425.25 raised at the game, nearly $20,000 gathered by Cohan’s newsboy efforts and evening theatrical performance.31 And no number could quantify the value of a pleasant afternoon diversion during a tumultuous week in which the national pastime helped humanity when it was most needed.

DAN VanDEMORTEL became a Giants fan in Upstate New York and moved to San Francisco to follow the team more closely. He has written extensively on Northern Ireland political and legal affairs, and his Giants-related writing has appeared in San Francisco’s “Nob Hill Gazette” and SABR’s “The National Pastime.” An investigation into the shooting of a spectator at the Polo Grounds will be published in 2017 in a Polo Grounds anthology. He is currently writing a book and related articles on the 1971 Giants and welcomes feedback at giants1971@yahoo.com.

Acknowledgments

My appreciation goes out to MLB historian John Thorn, Hall of Fame librarian Matt Rothenberg, and the New York Giants Preservation Society for their research assistance. Blessings to Ken Manyin’s proofreading eyes, to SABR stalwarts Stew Thornley and Greg Erion for reviewing parts of this article, and to Leslie Cassidy for tracking down information at the New York Public Library.

Notes

1 Mike Vacarro, The First Fall Classic (New York: Doubleday, 2009), 158.

2 Ibid., 208. A typical schedule of the times: Monday—Wash Day, Tuesday—Ironing Day, Wednesday—Sewing Day, Thursday—Market Day, Friday—Cleaning Day, Saturday—Baking Day, Sunday—Rest Day.

3 “The New Giantess Titanic,” New York Times, April 14, 1912; Robert D. Ballard, The Discovery of the Titanic (New York: Warner/Madison Press, 1998), 18.

4 Ballard, op. cit., 15.

5 James Barron, “After Ship Sank, Fierce Fight to Get Story,” New York Times, April 9, 2012, https://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/04/09/after-the-ship-went-down-scrambling-to-get-the-story/?_r=0.

6 Ibid.; George Behe (Titanic Historical Society), email message to author, May 8, 2017.

7 “Topics of the Times – Displayed Mild Enthusiasm,” New York Times, April 19, 1912.

8 “Women Sob as News Bulletins Appear,” New York Times, April 16, 1912.

9 “Rescue Ship Arrives, Thousands Gather at the Pier,” New York Times, April 19, 1912.

10 The Senate inquiry was transferred to and continued in Washington, D.C. the following week.

11 “American Press Comment on Titanic Disaster,” New York Herald (European Edition), April 18, 1912.

12 New York City, Encyclopedia Titanica, https://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org/titanic-places/new-york-city.html.

13 “Giants Divide Winnings,” New York Tribune, Oct. 24, 1910; “Mathewson Beats Yanks Fourth Time,” New York Times, Oct. 22, 1922. Each Giant and Yankee received an additional $190.29 and $120.79, respectively, for a played game that ended in a tie due to darkness. Each Giants player’s total share was also reduced slightly to apportion funds to the team’s trainer, masseur, and three players who were either no longer with the Giants or who joined the team late in the year.

14 John T. Brush and Frank Farrell, “The Human Side of Baseball,” Baseball Magazine, June 1912; Frank Farrell, “A Word on the Recent Benefit Game for the Survivors of the Titanic Disaster,” Baseball Magazine, June 1912.

15 Prior to the Titanic exhibition, this was the first and only Sunday game played by two major league teams in Manhattan. Walter LeConte, In-Season Exhibition Games (or ISEGs), http://www.retrosheet.org/Research/LeConteW/ISEG.pdf.

16 Ibid.; “Play for Newsboys,” New York Tribune, July 5, 1909. Brooklyn hosted the Yankees for a Sunday, July 4, 1909 exhibition game to benefit newsboys. Although technically the first in-season, inter-league exhibition game since the American League’s 1901 formation, the teams exchanged batteries to circumvent a National Commission (baseball’s then three-man governing body) rule forbidding inter-league exhibition games. It is unclear whether this edict was still in effect on April 21, 1912. If so, it was circumvented.

17 Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, Total Ballclubs, (Toronto: Sport Media Publishing, Inc., 2005), 392; Keith Olbermann, “End of Story: The 1912 New York Yankees,” MLB Pro Blog, http://keitholbermann.mlblogs.com/2012/04/21/end-of-story-the-1912-new-york-yankees/.

18 A last-place 50-102 finish loomed, stained by a league-leading, deplorable 384 errors. Manager Harry Wolverton intrigued with his sombreros and long cigars, but Farrell’s saloon and casino operations, Tammany Hall servitude, and racetrack and bookmaking activities dominated headlines.

19 Later that year, Brush was seriously injured in a Manhattan car crash. He died on November 26.

20 G.H. Fleming, ed., The Unforgettable Season (New York: Penguin Sports Library, 1982), 201.

21 Christy Mathewson, Pitching in a Pinch (New York: Stein and Day, 1977), 111.

22 Gabriel Schechter, “Charlie Faust.” SABR BioProject, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/d1ee8535.

23 Damon Runyon, “American Sports Pay Tribute to American Manhood,” New York American, April 22, 1912.

24 Stew Thornley, Land of the Giants (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000), 66.

25 “Who Was “Jack” Sullivan,” Newsies Historical Research, http://newsieshistory.tumblr.com/post/98207741743/who-was-jack-sullivan.

26 Ibid. Sullivan, aka Jacob Reich, real name John Abraham Rich, testified at the murder trial, was released from jail in 1913, and cleared his name in 1936.

27 “14,083 See Game for Charity,” New York Times, April 22, 1912; “Girl Wonders in Athletics,” San Francisco Chronicle, Oct. 30, 1921. Sources claim 1913 as the women’s first game. But, the Female Giants were likely already playing unreported games in 1912. Exhibition game coverage describes them as “a noted female baseball club.” Runyon, op. cit. Their box seat-presence demonstrates an obvious yet unclear connection to the Giants. One source, repeated by others, indicates they were probably created by McGraw. No available evidence confirms this probability, rendering it speculative. However, the Female Giants would be unable to fund-raise or use “Giants” without the approval of Brush and/or McGraw. McGraw’s affinity for and excursions to Broadway, and his friendship with Cohan, likely facilitated his introduction to Schnall. And a photo shows a Giants catcher participating with the women. “And Now the New York Female Giants: (Briefly) A League of Their Own,” Bowery Boys: New York City History, http://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2015/06/and-now-the-new-york-female-giants-briefly-a-league-of-their-own.html.

28 Fullenwider, who pitched the previous season for the delightfully-named Columbia Commies, was released on a one-way ticket to the minors two months later.

29 “Giants Too Rapid for Players from Hilltop,” New York Sun, April 22, 1912.

30 Ibid.; “14,083 See Game for Charity,” op. cit.; “For Titanic’s Victims,” Baltimore Sun, April 22, 1912; “Giants Toy with Yankees,” New York Tribune, April 22, 1912.

31 Attendance was 63% higher than the 8,621 Giants season average.