A Giant’s Fall (To Minneapolis): Future Hall of Famer Dave Bancroft Reluctantly Guides the Millers’ Tumultuous 1933 Season

This article was written by Tom Alesia

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Land of 10,000 Lakes (2024)

The Minneapolis Millers’ 1933 home opener featured three-seat bicycles during the pregame parade to the team’s venerable but odd-shaped Nicollet Park. The bikes weren’t the only unusual sight as the Millers began to defend their first American Association title since 1915. That gloomy late April day, with temperatures in the 50s, locally made product, Wheaties, debuted their new national advertising slogan “The Breakfast of Champions” on a billboard inside the park.1

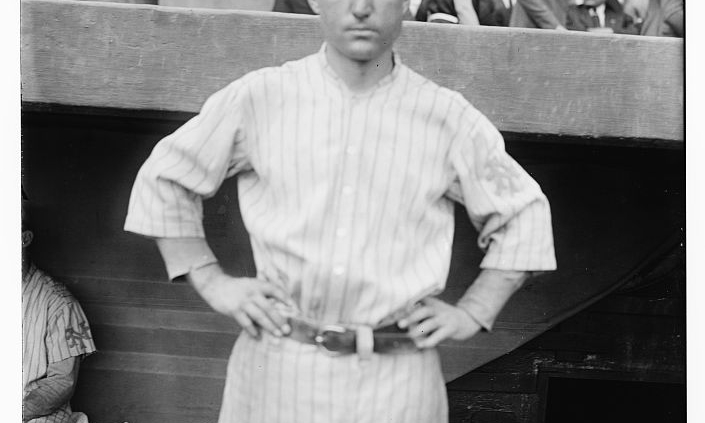

After their perfunctory first-pitch duties, Minnesota Governor Floyd B. Olson and several city politicians took batting practice. A three-man comedy team, featuring “Snooze” Kenneard, roamed through the sizable crowd of 8,064 and six—six!—bands entertained fans. At the center of this circus was the Millers’ new manager, Dave Bancroft, slight in build and gray haired just four days after he turned age 42.

The longtime northwestern Wisconsin resident, with enough spitfire to start a car, reluctantly took the job after 18 years in the National League. During his career, the 1971 Hall of Fame pick became one of the finest defensive shortstops; played in four World Series, including two winning teams; served four years as the Boston Braves player-manager; and, from 1930 to June 1932, was legendary skipper John McGraw’s closest associate with the New York Giants.

Early in the 1932 season, Bancroft often led the Giants at spring training in Los Angeles and became interim manager on multiple road trips when McGraw wasn’t available. But that June, when McGraw’s health prompted him to quit, team officials named star Bill Terry as player-manager. Bancroft was simply too much like the fiery old-school McGraw to replace him. As an indication that the Giants were going in a different direction, Terry’s first managerial decision was to end curfews. Terry asked Bancroft to remain as assistant coach, but he politely declined.2

So, after the 1932 season, Bancroft sought the vacant Cincinnati Reds managerial spot with the subtlety of a squirrel scrambling toward a walnut. Despite McGraw’s efforts to help him, the Reds picked Donie Bush, who had led the Millers to 100 wins in 1932, his first season in Minneapolis.

Bush’s departure led Millers owner and president Mike Kelley to search deeply to maintain the team’s momentum. Minneapolis papers named more than 20 candidates, ranging from former major leaguer and vaudeville star Mike Donlin to Bancroft’s Giants teammate Heinie Groh. None mentioned Bancroft.

But Kelley, a former player and manager himself, pursued Bancroft and landed him for a $7,500 salary— high for the minor leagues, which sought to cut costs during the Great Depression. Minneapolis newspapers responded with zeal. One said the worst part of Bancroft’s hiring was that the season didn’t begin for another five months. Another paper presented a six-part series on Bancroft’s playing career. Within one week of Bancroft’s hiring, however, New York Telegram sportswriter Dan Daniel predicted that “Bancroft will not linger long in minor company.”3

At the opening game, the Minneapolis Star reported that Edna Bancroft, “attractive wife of the new Minneapolis manager,” sat directly back of first base, where she would be for virtually all 76 home games. She saw her husband of 22 years struggle through the Millers’ 13–8 “riotous victory.” In the game’s first three innings, the Toledo Mud Hens pounded Millers starting pitcher Harry Holsclaw for six runs, prompting the Minneapolis Journal’s Jack Quinlan to wisecrack, “Holsclaw was just coleslaw.”4

The game signaled what Bancroft already knew about the Millers’ depleted pitching staff. In addition, just 20 games into the season, the team’s leading hitter from 1932, Joe Mowry, was traded to the Boston Braves for two players and $25,000. At the time of the deal, Mowry was batting .360. His absence would leave a big gap.

Before the Millers’ spring training at the Campton Bowl, a Montgomery, Alabama, football stadium with a baseball field carved into it, Bancroft had tried to sign pitcher Clarence Mitchell, one of three remaining spitballers allowed to use that pitch in the National and American Leagues due to a 1920 “grandfather clause.” Mitchell rejected Bancroft’s request, leaving Bancroft to rely on former teammates Jess Petty, 38, and Rube Benton, who at 43 was playing the last of his 24 pro seasons.

The Millers offense was bolstered by slugger Joe Hauser, who hit 69 home runs in 1933, thanks to Nicollet Park’s unusual right-field fence. Though two billboards high, the fence was a mere 279 feet, 10 inches from home plate. By late August, the 34-year-old Hauser had hit 62 homers and was showered with gifts during Joe Hauser Day at Nicollet Park. He received $500 raised by fans, a diamond ring “from the women fans,” an electric toaster, three large cakes, and boxes of cigars.5 A rainout of the Millers’ final regular season game kept Hauser from a chance at 70 homers, but Babe Ruth still sent him a fawning telegram. Hauser’s 69 homers were an astounding 36 more than the runner-up. It was the second time he’d hit more than 60 home runs in a single season.

Bancroft pushed the Millers as they scrambled to a playoff berth, taunting umpires along the way. He was ejected from many games, although with a month left in the season, he insisted it hadn’t been 47 times, as suggested by one sportswriter. He claimed that the minor-league umps tossed him from games for infractions that wouldn’t receive similar punishment in the majors. Still, Bancroft boiled over. “Why don’t you try to bear down for just one game,” he shouted as he approached an umpire.6

In another game, Bancroft was ejected while walking toward umpire Jeff Pfeffer with his arms raised in disgust over a disputed strike call.

“But I didn’t say anything to you,” Bancroft screamed.

“No,” the ump said, “but it was your actions.”

Bancroft snapped back: “Well, what about your actions?”7

The Millers also used Bancroft as a promotional tool. In a pregame gimmick, he raced tap dancer Bill Robinson, one of the world’s most popular Black entertainers during the first half of the twentieth century. Robinson, 55, was given a 20-yard handicap against Bancroft and won the race by 15 yards—despite running backwards the whole time.

In an early July game, the Millers were foiled by a stray dog that scurried across the Nicollet Park field, delaying the game for five minutes. Third baseman Babe Ganzel caught the dog with a flying leap but was bitten sharply on two fingers and had to sit out for a week.

Kelley and Bancroft sought players to boost the Millers lineup after injuries. In mid-July, Kelley signed Bob “Fats” Fothergill, a 12-year American League veteran, despite his constant weight problems. Fothergill—described as 5-foot-10 and (charitably) 230 pounds—played 30 games as an outfielder with the Millers before retiring from organized baseball.

The Millers inched ahead of the crosstown rival St. Paul Saints and earned themselves an 86–67 record, making them the underdog in a best-of-seven championship series against the Columbus Red Birds. Columbus won two of the first three games at home, in part thanks to the pitching of 21-year-old Paul Dean, Dizzy Dean’s younger brother. But when the series moved to Minneapolis, the Millers won the fourth game, 6–4, before 10,000 frenzied fans at a sold-out Nicollet Park. Columbus followed up with a Game Five victory in 10 innings.

Game Six “was the most exciting baseball game seen here in years,” Minneapolis Star sportswriter Charles Johnson wrote. Unfortunately, it was bittersweet. With the Millers leading, 11–10, in the top of the ninth, first baseman Hauser misjudged a catchable foul pop with two outs. The batter, Lew Riggs, then hit a two-strike pitch over Nicollet Park’s short right field fence.

In the bottom of the ninth, Minneapolis couldn’t score despite placing runners on second and third with no outs. In the top of the 10th, Ralph Judd, a struggling relief pitcher and fair hitter who had narrowly avoided being cut from the team a few weeks before, hit a three-run homer that barely cleared the not-quite 280-foot fence to secure the championship for Columbus.

The epilogue to Bancroft’s lone and lively season with the Millers is filled with remarkable coincidences and missed opportunities. On the day Columbus won the American Association series over Minneapolis, Bill Terry’s New York Giants locked up the National League title. Terry—whom Bancroft had supported publicly several times in 1932 as the Giants floundered—then led the Giants to the 1933 World Series crown.

In early October 1933, Bancroft formed an auto dealership in Minneapolis while still serving as the Millers manager. One month later, Kelley announced that Bancroft’s one-year contract wouldn’t be extended. Bancroft then stung Minneapolis fans when he said he expected to land “something better” than the Millers managerial position.8

The idle Donie Bush, who had been fired after the Reds finished last in the National League, signed with Kelley to return as Millers manager in 1934. Bush remained for another five years, leading the Millers to an American Association title and helping prepare a 19-year-old Ted Williams for his major-league debut in 1939.

On December 18, 1933, the United Press announced that Bancroft would become the Reds’ new manager. Instead, the job went to former St. Louis Cardinal Bob O’Farrell, who lasted all of 90 games before being fired with a 30–60 record.

Bancroft’s friend and mentor, John McGraw, died on Feb. 25, 1934. “I am so hard hit,” Bancroft said, “I can hardly talk.”9 Without McGraw’s support, Bancroft’s major-league coaching career came to an end. In 1947, he managed the St. Cloud (Minnesota) Rox for one season. Then he spent four seasons as manager in the All-American Girls Baseball League before returning to his Superior, Wisconsin, home with his wife, Edna, where he became a warehouse supervisor whose baseball career was largely unknown to his co-workers.

In January 1971, Hall of Famer Terry and New York sportswriter Daniel (the one who predicted that Bancroft wouldn’t be in the minors for long) were members of the 12-person Veterans Committee that elected Bancroft to the Hall of Fame. When reached by a Milwaukee reporter with the news, Bancroft, nearing 80 and in failing health, beamed. “That’s the nicest thing I’ve ever heard,” he said.

TOM ALESIA is the author of one of 2022’s best-selling baseball books, Beauty at Short, the snappy and entertaining biography of Hall of Famer Dave Bancroft. A Madison, Wisconsin, resident, he worked for nearly three decades as an arts and entertainment writer for Midwest newspapers and was the winner of the National Music Journalism Award. His website is www.TomWriteTurns.com.

Notes

1 Stew Thornley, “Nicollet Park,” undated, StewThornley.net, https://stewthornley.net/nicollet_park.html.

2 Associated Press, “Terry Full of Ideas,” Tampa Times, June 4, 1932, 10.

3 “Daniel lauds Dave Bancroft,” Minneapolis Star quoting New York Telegram, December 7, 1932, 14.

4 Jack Quinlan, “The Sounding Board,” Minneapolis Journal, April 28, 1933, 31.

5 “Truckload of Gifts Presented to Hauser,” Minneapolis Tribune, August 27, 1933. 34.

6 “Miller Notes,” Minneapolis Star, April 29, 1933, 10.

7 Halsey Hall, “Saints Take Win from Millers,” Minneapolis Journal, May 14, 1933, 12.

8 Associated Press, “Dave Bancroft ‘Frank to Say’ He Wouldn’t Mind Managing Reds,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, December 17, 1933, 11.

9 Associated Press, “Dave Bancroft Is Shocked By Death Of Veteran Leader,” Birmingham News, February 26, 1934, 12.