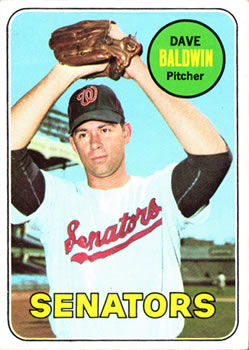

Dave Baldwin: A Player’s View of Scouts in The 1950s

This article was written by Dave Baldwin

This article was published in Can He Play? A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession (2011)

My first contacts with baseball scouts occurred in 1955 during my junior year at Tucson High School in Arizona. These were always casual meetings — a scout might “happen” to bump into me after one of our games, introduce himself, and toss an off-handed compliment such as, “That’s some fastball you have there, kid.”

My first contacts with baseball scouts occurred in 1955 during my junior year at Tucson High School in Arizona. These were always casual meetings — a scout might “happen” to bump into me after one of our games, introduce himself, and toss an off-handed compliment such as, “That’s some fastball you have there, kid.”

The first scout to speak to me was with the Boston Red Sox. I don’t remember his name (it was probably Tom Downey — I still have his business card), but “Red Sox” is well ingrained in my brain. This was a big moment for a kid. As soon as I could get to an encyclopedia, I looked up Boston. I read all about Paul Revere, the Old North Church, and anything else I could find about the city. I already knew the names and stats of all the Red Sox (in those days it was easy for a kid to memorize all the rosters of the 16 MLB teams). Given the chance, I would have signed with the Red Sox right then and there.

And that is pretty amazing, considering I was a firm Cleveland Indians fan. The Indians took spring training in Tucson each year, and I had tried to model myself after their great pitchers of the 1940s and ‘50s. But a kid’s first contact with a scout is a powerful experience, enough so to make him switch allegiance immediately.

After that Red Sox contact, scouts were a part of my life for the next four years, until I signed with the Phillies in June of 1959. Their attention was heady stuff for a kid. They represented the opportunity to play pro baseball, and that was the big dream of a boy growing up in Tucson in the 1940s and ‘50s. Baseball was our major sport in those days, so we had a whole city full of kids trying to catch the notice of the scouts.

But the scouts were careful about what they said to kids. Each high school was touchy about its students being persuaded to drop out of school for professional contracts. So, until high — school graduation, scouts were low — key. As soon as the school’s administration was no longer an obstacle, however, scouts started pitching their organizations to the prospects.

The Scout’s Job

Before the amateur draft was first implemented in 1965, each scout was both an evaluator of talent and a salesman. A scout finding a raw superstar in some godforsaken outback makes a good story, but in the real baseball world this rarely happened. The top prospects became that way by playing in a lot of games, so to find them, a scout attended as many scholastic and semipro games as he could find. This was in the days before the invention of electronic measuring devices such as radar guns — when scouts needed to assess players by eye, or in the case of power hitters, by the old-fashioned tape measure. Scouts had to predict whether players as small as Bobby Shantz and Yogi Berra could make it to the majors. But it did no good to find a hot prospect if the scout couldn’t convince the player and his parents that there was just one baseball team that would give the kid the opportunity he deserved. The most successful scouts were those who had the best sales techniques.

I recall that scouts concentrated on “courting” my parents when I was playing semipro ball the summer after my high-school graduation. An 18-year-old probably will listen to his parents’ advice, so this was a good strategy. Some scouts took my mom and dad out to dinner at Tucson’s better restaurants. Some, such as Lefty Phillips of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Bob Fontaine of the Pirates, ate lunch at our house and were gushingly complimentary to my mom about her cooking (they were right — she was a good cook). They sent extremely polite thank-you cards to her within a couple of days. I imagine all scouts carried a whole briefcase full of such cards as part of their required paraphernalia.

In 1953 my dad built a catching device that gave me a strike-zone-sized target and returned each pitch to me. I continued to throw to that device until I retired from pro ball 22 years later. The scouts were fascinated by this invention. Some heard about it through the scouting grapevine and made a special trip to our house in the desert northeast of Tucson just see “the box,” as it was called. They were just as intrigued by the batting cage that my dad added in the hopes that I might actually be able to hit the ball someday. It didn’t work — I was a terrible hitter — but the cage was great entertainment for the scouts. As I wrote in Snake Jazz, my baseball memoir, “A few couldn’t resist taking some swings. I can remember Babe Dahlgren [a Kansas City Athletics scout at the time] hitting dozens of line drives against my dad’s pitching. After each one, he implored, ‘Just one more.’ Dad was having the time of his life.” Then Babe was treated to my mom’s fried chicken. Scouting just didn’t get any better than that.

For any scout representing a team playing spring-training games in Arizona, it was common practice to invite the whole family out to the local ballpark to watch his team in action, implying that in no time at all, “Your son could be playing for us.” I found a letter (among the few scouts’ memorabilia I have left) from Paul Richards dated March 14, 1958, when he was field manager and general manager of the Orioles. The letter begins, “Babe Dahlgren has told me about you…” and ends, “Please present this letter to Mr. Jack Dunn … and he will arrange to get you into the ballpark and to our bench.” Unfortunately, I was to pitch for the University of Arizona on the day the Orioles were playing in Tucson, so I never met Mr. Richards.

On another occasion, Bill Veeck sought out my dad and sat with him through one of my games. I don’t think he owned a team at the time, so he wasn’t looking to sign me. He just wanted to talk baseball with my dad.

No Longer a Prospect

Once I had enrolled at Arizona, scouts concentrated on selling their teams to me rather than to my parents. They would take me out to lunch and suggest that I might advance my baseball skills faster by pitching full-time. “Not that school is a bad idea, mind you, but you could be pitching a lot more innings if you sign with the [fill in the name of the team], son.” I always explained that I was adamant about playing college ball for three years, and the scouts never pressed me to sign.

In the late 1950s, NCAA rules were such that if I pitched on the varsity as a freshman, I wouldn’t be eligible for tournament play, including the College World Series, during my freshman year or my senior year. Frank Sancet, the Arizona coach, figured I would probably sign before I was a senior anyway, so he asked me to play varsity ball my freshman year.

I had a good freshman season and some good performances in the national semipro tournament in Wichita, Kansas, in 1957. I remember that Tom Greenwade of the Yankees took me out to lunch in Wichita, and I was very impressed that the guy who signed Mickey Mantle would even talk to me. The scouts were still sending me Christmas cards, and calling and writing frequently, checking as to whether I intended to stay in school. Then, on March 24, 1958, in the sixth inning of a game against the University of Utah, I threw the curveball that changed my career. My elbow was badly damaged and suddenly I stopped being a prospect. I didn’t hear again from a scout until near the end of my junior year in 1959.

By the time I was ready to sign, only two teams — the Phillies and the Yankees — were still interested. The other teams had turned cold on me because of the arm injury, but there was more to it than that. At that time, teams wanted to get their prospects into their farm systems as early as possible. Most organizations weren’t keen on signing players out of college — they felt the competition was much better in pro ball. But, I had faced a number of hitters in college and semipro ball who were as good as or better than hitters playing in the lower or mid-minor leagues.

The Phillies and Yankees didn’t show this strong anti-collegiate bias. For example, in 1959 my first pro team (Williamsport, Pennsylvania, a Phillies farm team) had around 10 players who had played college ball; in 1960 Williamsport had 12 former collegians. The two scouts who talked to me in June of 1959 were Danny Reagan (Phillies) and Gordon Jones (Yankees). Each offered me a small signing bonus, and each persuaded effectively using all the expected arguments. I signed with the Phillies for one reason — the Yankees were still the most powerful organization in baseball and seemed loaded with talent. The Phillies, on the other hand, had finished last in the National League in 1958 and appeared to have a much greater need for pitching.

Few Mementoes

Early on in my pro career I was moving often and saw no reason to keep packing up all the business cards, Christmas cards, birthday cards, and letters I had accumulated. Now, too late, I wish I had kept them. I don’t even have the business cards of the last two scouts to talk to me — Reagan and Jones. I still have one Christmas card (from Tom Downey) and several business cards from Downey, Lefty Phillips, Hugh Alexander (Dodgers), Gene Handley (Cubs), Roy Johnson (Cubs), Babe Dahlgren, Al “Zeke” Zarilla (Athletics), Walter “Dutch” Ruether (New York Giants), Walter Laskowski (Phillies), Tom Demark (Phillies), Bob Fontaine, and Art Asmus (Senators). I also have a collection of handwritten notes from my mom telling me the Cardinals, Tigers, or White Sox called. And nothing more remains of that exciting time in my life.

DAVE BALDWIN pitched for 16 professional seasons, including parts of six seasons in the majors. His major-league record was 6-11 with an excellent 3.08 earned run average.