A Season-Ending Doubleheader and its Impact on the 1966 World Series

This article was written by David E. Skelton

This article was published in Fall 2014 Baseball Research Journal

Seldom are the occasions when a team emerges as back-to-back champions in the National League. Rarer still when that team’s manager could call upon a well-heeled mound corps that includes three future Hall of Famers.

These were the well-earned privileges of Walter Alston as his Los Angeles Dodgers entered as 8–5 favorites against the Baltimore Orioles in the 1966 World Series. Yet despite these advantages, the events of October 2, 1966, would cause Alston to enter Game One without the immediate services of reigning Cy Young Award winner Sandy Koufax. Did this setback affect the outcome of the Series? If the lefty described by Jackie Robinson as “the greatest pitcher in the history of baseball”1 had started the first match, would it have magically transformed a Dodgers team that set numerous records for offensive futility?

Though Koufax’s presence in Game One may have altered the eventual outcome—ensuring a second start that, at a minimum, might have avoided a four game sweep—the purpose herein is not to dwell on the counterfactual Dodgers championship. The narrative instead seeks to chronicle the waning days of the 1966 season that eventually tied Alston’s hands, including the event-filled season-ending doubleheader in Phila-delphia three days before the start of the World Series. Connie Mack Stadium’s twin-bill witnessed three Hall of Fame pitchers in starting roles, a fourth hurler becoming the Phillies’ first 20-game winner in more than a decade, and a peculiar ongoing dominance over one of the future Hall inductees. The nail-biting finish was the pinnacle of the long-fought three-team National League pennant race.

“It doesn’t look as though anyone wants to win it.” 2

The frustration was expressed by Alston as his team was concluding August with a pedestrian 15 wins in 30 contests. He found solace in the knowledge that his closest competitors—the San Francisco Giants and Pittsburgh Pirates—were struggling similarly across the 162-game campaign. Solidly built around speed, fielding, and superb pitching, the Dodgers limped into September with righty stalwart Don Drysdale sporting a record of 9–15. Seeking to describe his struggles, Drysdale alluded to his prominent role in a popular television ad when stating, “The way I’ve been pitching I couldn’t get a commercial stitching baseballs. Maybe I could work up a show on how to unstitch them. I’ve had a few unstitched on me this season.”3 For his part, general manager Buzzie Bavasi cited an out-of-condition Drysdale for these struggles. He bitterly recalled the much-chronicled Koufax-Drysdale pre-season holdout, and rumors emerged that Bavasi was dangling the righty on the trade block.4,5

But the team’s malaise could hardly be laid solely on the doorstep of one hurler. Despite a slow start to the season, Drysdale had strung together 17 consecutive outings with a 3.25 ERA (league average: 3.61). In that stretch of 17 starts, which ended on August 31, he garnered a scant five wins. The world champions were often plagued by an anemic offense. Among the bottom-feeders in runs scored 1964–66, they would become the first pennant winner from either league to be shut out 17 times (a dubious feat matched only by the 2005 Houston Astros). As the Dodgers entered September trailing the pace-setting duo of the Pirates and Giants by three games, the ongoing struggles hardly appeared conducive to a repeat championship. A September surge from outfielders Lou Johnson (.308) and Ron Fairly (.397)—neither of whom threatened memories of Murderers Row—helped propel the Dodgers toward a Series berth. But they were assisted mightily by the struggles of their closest competitors.

“If you blow the pennant, [it] will be a collector’s item.” 6

A quotation delivered in late-August by a New York sportswriter to Pittsburgh manager Harry Walker, the “it” was a picture of Pirate players adorned in oddball hats sporting the relaxed atmosphere of a team seemingly destined for postseason play. The Pirates had recently (August 26) rewarded their sophomore skipper with a new one-year contract. At approximately the same time the team’s traveling secretary was busy booking hotel reservations in Baltimore in anticipation of a Fall Classic against the Orioles, while former manager Danny Murtaugh began scouting the Birds. A team makeup nearly the complete opposite of the defending champions, the Pirates vaulted into contention primarily from offensive heft. Aamong the league leaders in runs scored, they managed this feat with a major-league leading .279 average. Having seized a stake in first place through 40 percent of the season, the Pirates never built more than a two-game lead over their fiercest competitor, the Giants. But their sizzling start would yield to a 32–30 finish that doomed their pennant pursuits.

The team’s shortcomings were plentiful. Though they showed themselves quite capable of beating up on less-talented clubs, possessing a .722 winning average over the second-division trio of the Houston Astros, Chicago Cubs, and New York Mets, they fared less well (53–55) against the rest of the league. This trend was mirrored by slugger Willie Stargell who feasted on the bottom-dwelling trio (.392, 20 homers) but struggled against the Dodgers and Giants (.259, two homers). As second half losses mounted, the manner in which defeat presented itself became ever more striking. For example, on August 17 lefty ace Bob Veale (who yielded 18 homers in 1966, 13 more than the preceding year) was staked to a 7–1 lead over New York when he surrendered the Mets’ first franchise pinch grand slam,7 a blow that contributed to an eventual 8–7 Pirate loss. The next day third baseman Jose Pagan committed four errors—three in one inning—that only added to the enduring losses. Rotation members Veale, Woodie Fryman, and Steve Blass combined for a 14–18 record after July 9, prompting the team to pursue a desperate search for additional hurlers—inquiring of the California Angels and Washington Senators for veterans Jack Sanford and Mike McCormick, respectively.8,9 The offense was crippled when a knee injury limited Stargell to two plate appearances in the final six games. Further insult was inflicted when Phillies ace Jim Bunning earned his first relief win in nine years in a victory over the Pirates on September 26.

The death knell arrived October 1 when the Pirates were swept by the Giants in a doubleheader at home, putting the final touch on the second-half collapse. Unknown is whether the picture of the players sporting oddball hats was preserved.

In his previous World Series appearances, Sandy Koufax held a 0.88 ERA and a 4–2 record. But going into the 1966 Series, in order to get two starts, he would have had to make two consecutive starts on two days’ rest.

UNEARNED RUNS ALLOWED: 95

Though no quotation exists to encapsulate the Giants’ ill-fated campaign, the above number says it all. Only the Astros exceeded the error total of the Giants’ porous defense, which haunted the team by season’s end. Seemingly poised to overcome this deficit with the combined best features of the Dodgers (two superb front line pitchers) and Pirates (ferocious hitting) the Giants were considered preseason favorites with an All-Star cast of future Hall of Famers Juan Marichal, Gaylord Perry, Willie Mays, and Willie McCovey. But the team’s glove play had a direct impact on at least 10 of the team’s 68 losses, some of which were excruciating. For example, an opportunity to place distance between themselves and Los Angeles went awry as far back as May 17 when a throwing error in the 13th inning led to a Dodgers victory, whereas three errors on June 10 resulted in three unearned runs that provided an additional margin for a Koufax win. Lacking the killer instincts of the Pirates, the Giants did not fare nearly as well against the Mets and Cubs. Nursing an early 2–1 lead over New York on July 21, a fourth-inning error resulted in a rare five-run Mets explosion and an eventual 14–3 loss. On September 9, after an extended road trip in which they lost a stake in first place, the Giants had an opportunity to make up ground with a home series against the Cubs. Ten errors—including five in the series opener—contributed to three straight losses against the last-place team and pushed the Giants further south in the standings (third place). If the Giants had prevailed in any one of these lead-gloved affairs, the World Series might have seen a different National League contender, as a win would have put them only a half-game out of first place.

In the end, pitching also proved a liability despite two 20-game winners, the first such franchise occurrence since the New York Giants in 1951. They made an attempt to bolster the rotation by acquiring former 20-game winner Ray Sadecki from the St. Louis Cardinals nine days after the lefty hurler handcuffed the Giants on April 29 with a five-hit, complete game victory. The acquisition came at a dear cost—Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda—while Sadecki would garner a mere three wins in 26 appearances for the Giants. The mound problems were further compounded when Perry, 1966’s first 20-game winner in the majors, collapsed to 1–6 in his final ten starts, mirroring the team’s 6–11 crash that began August 24. The Giants were forced to scramble with a six-game winning streak at season’s end just to make things cozy. Having disposed of the Pirates in Forbes Field on October 2—a dramatic extra-inning affair worthy of its own chronicle, the winning run coming on a pinch-hit homer by McCovey—the Giants waited in the Pittsburgh airport for a hopeful doubleheader sweep of the Dodgers in Connie Mack Stadium. If the Phillies held up their end of the bargain, the Giants would be forced to play a make-up game washed out August 10 in Cincinnati. A postponed win—not a sure bet after Reds manager Dave Bristol chose to hold back two-time 20-game winner Jim Maloney for just such an event—would result in the second Giants-Dodgers playoff pairing in four years. That series had evolved from a late-season collapse of the 1962 Dodgers. In 1966, after a lethargic August, there were no signs of a similar fall from the boys in blue.

A Weather-Induced Doubleheader

When the Pirates were taking a final account of the concluded 1966 season, manager Harry Walker pointed to a September 1 loss to the Dodgers “as the turning point for his club. ‘The score was tied 1–1 [at home] going into the ninth and we lost. We would have been four games out in front, but we ended with a two-game lead instead.’”10 (Note that although they would have been four games ahead of the Dodgers, they would only have been one game ahead of the Giants.) On that date, rookie Don Sutton had hurled an inspiring nine innings of four-hit ball that helped ignite a month-long surge for Los Angeles. Entering the season’s last weekend, the Dodgers had raced to a 20–8 mark—including a club-record four consecutive shutouts—that pushed the team to the top of the standings (see above). One win in the three-game series in Philadelphia guaranteed elimination of the Giants and, at a minimum, a playoff series versus the Pirates. In the past Philadelphia had proven to be of little challenge, having lost 10 of 15 to the Dodgers that season. But on this weekend the Phillies suddenly exhibited an Alamo-like stand.

Relishing the role of spoiler, Phillies manager Gene Mauch took a page from Dave Bristol by ensuring that his ace, Jim Bunning, would be on the mound for a potentially decisive third game. To make it so, the Phillies would have to win both of the preceding two games. In the first match lefty Chris Short, after escaping a bases loaded first inning jam, handcuffed the Dodgers to earn his 19th victory of the season. The win placed focus on the next day, but weather would play its own part in the developing drama.

Philadelphia struggled throughout September attempting to complete its scheduled home games. In 1966 the region experienced its second wettest September—and wettest October—in 50 years and rain had forced the club into a doubleheader against the Pirates just three evenings earlier. October 1 would not be spared when yet another deluge set the stage for the season-ending twin bill. Though precipitation afforded Alston’s next starter an additional day’s rest, the selection itself was wrought with its own challenges.

OCTOBER 2, DOUBLEHEADER: Game One

It was Drysdale’s turn in the rotation. A miserable season’s start flourished into a far more profitable 8–5, 2.51 mark in his preceding 20 starts that successfully quieted the trade rumors. With sound reasoning, a victory from his star hurler would allow Alston to enter the World Series with the lefty who made the Cy Young Award a staple of his personal effects.

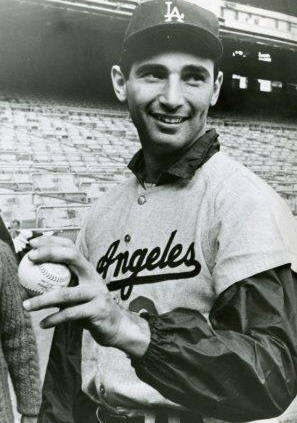

The illustrious 14-year career of Don Drysdale was witness to nine All Star selections, two 20-win campaigns and a 1962 Cy Young Award. A well-earned reputation for sending hitters sprawling should they dare claim a too-healthy stake in the batter’s box, this fierce competitor found eventual reward with a 1984 Hall of Fame induction. But despite this success, the righty was oft-tested by the Phillies, a team that was hardly considered “world beaters.” Starting in 1963, he suffered nine consecutive losses to the Quakers that contributed to a 6–12 record throughout the remainder of his career. When he added to his Hall resumé a record-setting scoreless streak in 1968, it was the Phillies that would bring the streak to a halt. This peculiar hex continued when the first batter in the October 2 match parked a pitch into the seats. The next batter walked and two singles later the Phillies grabbed a 2–0 lead. With the quick indication that the jinx was still very much alive, Drysdale was lifted in the third inning as reliever Ron Perranoski successfully extinguished another scoring threat with three successive strikeouts.

But the feeble Dodger offense, held to two hits through five innings, rallied in the sixth. Following a walk and a groundball single, left-handed hitter Ron Fairly connected with a massive drive over the stadium’s right field steel wall that provided a 3–2 Dodger lead. Though both teams threatened—including a right field-to-second baseman-to-catcher relay that nabbed Dodger second baseman Jim Lefebvre at the plate—the score remained in LA’s favor until the bottom of the eighth.

In 1965–66 the Dodgers placed among the league leaders in fewest errors committed, a strength that unraveled this day. Reliever Bob Miller, who had succeeded Perranoski on the mound, survived a sixth-inning boot but he and Phil Regan would not be as fortunate in the eighth. Two errors sandwiched around an intentional walk contributed to two Phillies runs with more seemingly on the horizon. With the bases loaded and no outs, Regan managed a strikeout, a force at home, and a fly out to quell further damage. The strikeout was against opposing pitcher Chris Short, and sentimentality may have played a factor in Mauch’s decision not to pinch-hit for the lefty hurler.

The hometown crowd cheered when Short, a longtime fan favorite, began warming in the bullpen before the eighth inning. Emerging on the Philadelphia scene in 1959, he suffered through many lean years when last place remained the sole possession of the Phillies. As he entered the eighth inning on one day’s rest—Mauch obviously pulling out all the stops—every fan knew the import. Having captured the lead, if Short could set down the Dodgers in the ninth he would become the Phillies’ first 20-game winner since Hall of Famer Robin Roberts in 1955. With the crowd standing on each pitch, Short disposed of the Dodgers three-up, three-down, providing the stubborn Phillies with the hard-fought victory. Mauch would turn to his ace, Jim Bunning, to duplicate Short’s 20-game feat and upset the Dodgers’ pennant pursuits.

Odd things happen during pennant races. Phillies ace Jim Bunning earned his first relief win in nine years in a victory over the Pirates on September 26.

OCTOBER 2, DOUBLEHEADER: Game Two

In order to avoid a potential Dodgers-Giants playoff series, Alston was now faced with a must-win situation. In the clubhouse between games he urged his team on, stating “[W]e don’t want to back into the World Series.”11 To ensure against this, he turned to his lefty ace on two days’ rest.

Koufax entered the game lacking the difficulties encountered by his righty teammate. He possessed a .724 winning percentage against Philadelphia—highest against non-expansion teams. Impressive as this was, he was going up against an equally formidable opponent.

Since his debut in the National League in 1964, future Hall of Fame inductee Jim Bunning had faced the Dodgers ten times. His 2–4 record was accompanied by an impressive 2.33 ERA. His league resumé entering the game included two All-Star berths, a perfect game, and an overall mark of 57–20. Meanwhile the Phillies, with the second-best home record (a .600 winning percentage, trailing only the Dodgers), were closing out the season with a remarkably strong run—.630 winning average in its preceding 27 outings.

Bunning appeared to throw down the gauntlet early by striking out the first two batters in a one-two-three first inning. The Phillies then threatened to score immediately with runners on first and third with one out. Koufax quickly rallied, striking out feared slugger Dick Allen and inducing the next batter to ground out to end the inning. The Dodgers drew first blood with a three-run third, then added another in the fourth. A Dodger error in the Phillies half of the fourth opened another scoring opportunity that was lost when Koufax reared back to strike out first baseman Bill White and end the threat.

Trailing 4–0 with one out in the fifth, Mauch pinch-hit for Bunning in an at-bat that added yet another incredulous chapter to the career of Koufax: “Sandy was firing to Gary Sutherland when suddenly something popped high in his back, at the base of his neck. Koufax finished the inning and was rushed into the clubhouse…and had the slipped vertebra popped back in place. ‘You can sometimes pitch with something like that,’ said [trainer Bill] Buhler, ‘but you can’t move your head to check a man at first base.’ ‘Yeah,’ said Sandy. ‘It makes for great control.’”12

Great control was precisely what he delivered in yielding one hit over the next 31⁄3 innings, entering the ninth with a 6–0 margin. But an error followed by three consecutive hits brought the tying run onto the on-deck circle. Koufax reached back again to strikeout two of the next three batters and deliver the pennant to the boys in blue.

In the clubhouse afterward, Alston exclaimed, “If you don’t feel pressure in this situation, you’re not human,”13 while Koufax added, “It was the biggest ball game of my life…bigger than my pennant clincher [in 1965], or winning the seventh game of the World Series.”14 After a well-deserved celebration for having won back-to-back National League titles for the first time in eight years, the team soon witnessed the price paid.

The Giants tried to bolster their rotation by acquiring former 20-game winner Ray Sadecki for future Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda. But Sadecki would garner a mere three wins in 26 appearances after the trade.

SERIES SWEEP

Baltimore manager Hank Bauer anticipated a hard-fought match of at least six games. Alston echoed the sentiment stating, “The only way we can play the [Orioles] is the same way we played everyone else all year. We’ll peck away with singles and doubles and hope that our pitching can hold them.”15 Koufax had earned a World Series mark of 4–2, 0.88 entering the 1966 Series. Despite this impressive record Alston was reluctant to turn the lefty loose for what would have been two consecutive starts on two days’ rest.

Alston instead turned to Drysdale for the Series opener, seemingly well-rested after facing a scant 11 batters three days earlier. Big D possessed his own impressive post-season resume of 3–1, 2.43, but as evidenced above, 1966 had not looked kindly upon him. Identical to his Philadelphia outing, he induced a mere six outs as the Dodgers absorbed a 5–2 loss. His brilliant effort in Game 4 was not sufficient to stem the four-game sweep that handed the Orioles their first world championship.

Evidenced by his start in Game Two Koufax was not invincible, and the short turnaround four days earlier may already have taken its toll. Koufax “showed signs of weariness and loss of his rhythm in the fourth”16 inning of his October 6 start against Baltimore, and over the next two frames he surrendered a multi-error-aided four runs that contributed to the Baltimore sweep.

The team’s inability to dispose of the Phillies without assistance from Koufax robbed the Dodgers from entering the Fall Classic with their ace well-rested. Sandy accounted for more than 28 percent of Dodger wins in 1966, and his 27 victories could easily have been a 30-win campaign with a more productive offense—he absorbed six losses and three no-decisions while hurling a 2.21 ERA (league average: 3.61). Few pitchers have ever laid claim to such an enormous impact. The events of October 2 in Philadelphia prevented the Dodgers from opening the Series with “the greatest pitcher in the history of baseball.”17 Historians can argue the impact.

EPILOGUE

Six weeks after his World Series outing of October 6, 30-year-old Sandy Koufax announced his retirement from the game. The Dodgers would collapse to a distant eighth-place finish the next season and not witness postseason play again until 1974, when a fine rotation anchored by Hall of Famer Don Sutton was accompanied by a hard-charging offense (a luxury the mid- ’60s Dodgers lacked). In 1976 Walt Alston ended his successful 23-year run. He turned the managerial reins over to Tommy Lasorda whose own 21-year stint resulted in two world championships.

As the brilliant careers of Willie Mays and Juan Marichal began winding down, the Giants continued playing the role of bridesmaids. The duo experienced a measure of success when San Francisco faced Pittsburgh in the 1971 NLCS, but the Giants would not witness World Series play until 1989, while a championship wait lasted until 2010.

Following the 1966 campaign the Pirates experienced a brief collapse but emerged as one of the most dominant teams of the 1970s—with two championships in 1971 and 1979. A successful three-year run of post-season play 1990–92 yielded to a record 20 consecutive losing campaigns. They escaped this extended drought with a playoff appearance in 2013.

A seventh-grade classmate thought he saw me on the televised broadcast October 2 in the left field bleachers of Connie Mack Stadium. He claimed the camera panned to the “enthused youngster” egging his beloved hometown team to victory. That same enthusiasm—undoubtedly a necessary ingredient to any Phillies win—came up short in the second game of the season-ending doubleheader, but this 12-year-old took solace in the knowledge that Gene Mauch’s maneuvers had pressed the reigning world champions to the wall. That same solace would soon turn to regret.

A Phillies fan first, I was also a devoted National League fan and eager admirer of the Dodgers following their success in 1963 and 1965. Decades passed before I forgave the Orioles for the 1966 sweep.

DAVID E. SKELTON developed a passion for baseball early-on when the lights from Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium shone through his bedroom window. Long removed from Philly, he now resides with his family in central Texas but remains passionate about the sport that evokes many of his earliest childhood memories. Employed for over 30 years in the oil & gas industry, he became a SABR member in early 2012 after a chance — and most fortunate — holiday encounter with a Rogers Hornsby Chapter member.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Ryan Pollack and Bob Timmermann for invaluable input. Further thanks extended to Clifford Blau for editorial and fact-checking assistance.

Sources

Books

Leavy, Jane. Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy (New York, NY: Harper, 2002).

Periodicals

The Sporting News

Websites

Notes

1. “Jackie Robinson Cites Koufax as Fitness Example,” The Sporting News (October 15, 1966): 21.

2. “Dodgers Pack New TNT, But Who’ll Provide Spark,” The Sporting News (September 3, 1966): 11.

3. “Major Flashes—Big D Can Still Smile,” The Sporting News (September 24, 1966): 27.

4. “National League: Games of Thursday, August 18,” The Sporting News (September 3, 1966): 22.

5. Young, Dick. “Young Ideas: With Sandy Ailing, Dodgers Won’t Sell Don,” The Sporting News (October 14, 1966): 14.

6. “Who’s Buc Belter With Most? That’s Easy—Handyman Mota,” The Sporting News (September 3, 1966): 12.

7. ”Mets’ First Pinch-Slam,” The Sporting News (September 3, 1966): 21.

8. “Angels Ponder No. 1 Mystery: Chance’s Flop,” The Sporting News (September 10, 1966): 18.

9. “When Nats Hit Road, Even AAA Unable to Help,” The Sporting News (October 1, 1966): 17.

10. “Walker Proud Of His Buccos’ Stretch Battle,” The Sporting News (October 15, 1966): 8.

11. “Covington Douses Koufax and Alston With Champagne in Flag Celebration,” The Sporting News (October 15, 1966): 10.

12. Young, Dick, “Young Ideas by Dick Young,” The Sporting News (October 15, 1966): 14.

13. “Ducky Was No Quack at Hot Sack, Dodgers Discovered,” The Sporting News (October 15, 1966): 10.

14. Ibid.

15. “First Game Flashes,” The Sporting News (October 22, 1966): 8.

16. “Davis’ Three Boots Help Palmer Put Birds Two Up,” The Sporting News (October 22, 1966): 9.

17. “Jackie Robinson Cites Koufax as Fitness Example,” The Sporting News (October 15, 1966): 21.