A Second Strike: Baseball and the Canadian Armed Forces During World War II

This article was written by Stephen Dame

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

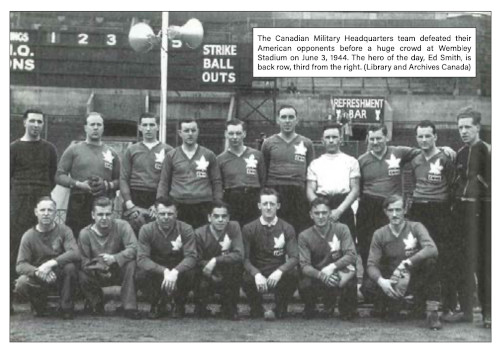

The Canadian Military Headquarters team defeated their American opponents before a huge crowd at Wembley Stadium on June 3, 1944. The hero of the day, Ed Smith, is back row, third from the right. (Library and Archives Canada)

Ed Smith was twice a hero during Canada’s Second World War. Smith, working at the Canadian Military Headquarters in London, never saw combat action. But on separate occasions, with his squad down to its last breath, he pulled off the improbable and delivered for Canada what seemed impossible victories.

During the final game of a three-game baseball series between Canadian and American military all-stars in 1942, the Canadian home side fell behind by six runs in the seven-inning affair. The Memorial Sports Ground in Red Hill was ringed by curious and supportive locals. They cheered as the Canadians rallied to tie the game, 9-9, in the sixth inning. In the bottom half of the final frame, the score remained tied. The Canadians managed to load the bases with two outs. Anything less than a hit would mean that the game, and the series, would end in an unsatisfying tie. Such a result would please neither King nor Country. Ed Smith, who was also pitching a gem that day, crushed a ball into the gap, clearing the bases. The Canadians won the game, 12-9. The Surrey Mirror and County Post, perhaps unfamiliar with the finer points of dramatic baseball writing, noted that “through skillful hitting and pitching, Sgt. Eddie Smith brought the Canadian score to twelve after the Americans were put out without adding to their total.”1 Smith picked up the win, the walk-off, and the series for his country.

Before shipping out, Smith was a renowned two-way player in Kingston, Ontario. Both he and his father had been standouts for the Kingston Ponies amateur team. He excelled also at football and hockey, and even boxed a little. Smith began his enlisted baseball career by playing games on Cockspur Street in front of the Canadian Military Headquarters in London. That career would reach its pinnacle before tens of thousands at Wembley Stadium. Smith played for nearly every Canadian all-star team assembled during the war.2

Three days before D-Day, Canadian and American soldiers gathered for a game at Wembley. Some 18,000 paying spectators watched the Canadian Military Headquarters take on the United States Central Base Section Salons. The US team took a 1-0 lead into the bottom of the final inning.

With two outs and the bases loaded, it was again Ed Smith who found himself at the front. This time, Smith fell behind early, taking two strikes from the American pitcher. Smith was known for his power hitting in Kingston, where in his youth he’d served as the Ponies’ batboy. During overseas baseball, Smith had also been recognized as a powerful righty on the mound.

In this moment, his bat was all that mattered. Smith carefully watched two close pitches sail by. He judged each correctly with his experienced eyes. The count now stood at 2-and-2. A crowd of that size, witnessing this particular sort of baseball drama, must have been thunderous. British fans, having become better acquainted with the game over the past four years, were experiencing the uniquely intense, cinematic, and anticipatory moments that baseball produces best. Perhaps some bit their nails. Others may have held their breath.

Ed Smith choked up, dug in and swung his bat. The Canadian sergeant hit a walk-off grand slam to claim the match for Canada by a score of 4-1. The ball was parked in the left-field bleachers, one of the most dramatic game-winning hits of the entire war.3

By the time Ed Smith and his fellow Canadians arrived overseas to contest a second world war, baseball’s relationship with the average fighting-age Canadian was significantly different from that of the previous hostilities. Hockey promoters, having pioneered Saturday night broadcasts, relayed by echoing radio affiliates across the country, had successfully turned their game into appointment listening. That broadcast exposure, placing a “Hockey Night” on every calendar in the country, coincided with the increased construction of indoor rinks in cities and small towns in every province and territory.

As a result, the interwar years saw hockey usurp baseball to become and remain Canada’s national game. Canadians still played baseball as a recreation, but that too was facing new competition. Softball, having gained popularity in North America shortly after the end of the First World War, was viewed as a more accessible and leisurely sport.

Regardless of the type of ball, or its place in the recreational pecking order, baseball still had a place in the hearts of Canadian men and boys. Accordingly, members of the Canadian military brass understood the value of the game, both as a training tool and as a way to occupy the time of idle troops awaiting battle. The first organized Canadian baseball games, after the declaration of war in September of 1939, took place in Sturgeon County, Alberta; Val Carrier, Quebec; Gagetown, New Brunswick; and the other permanent homes of the Canadian Army. On the first Dominion Day of the war, Camp Borden, west of Barrie, Ontario, held a sporting carnival which featured a tug-of-war and baseball game as the main events. These home-front baseball games often pitted the enlisted men against their superior officers. A record of the Camp Borden game does not include a final score, but concludes that the infantrymen demonstrated “a lack of training”4 both as soldiers and ballplayers.

The first Canadian soldiers arrived “over there” by way of Greenock, Scotland, on December 25, 1939. The early “Phony War” months of the conflict created similar conditions to those that allowed military baseball to flourish during the First World War. A sedentary army needed to do something to pass the time, stay in shape, and maintain its esprit de corps. John Maker, of the Laurier Centre for Military, Strategic and Disarmament Studies, wrote that “because soldiers were forced to ‘hurry up and wait,’ many for 42 months or more … sports served as an essential tonic to the soldiers who were eagerly awaiting action.”5 Baseball and other games mitigated discipline and morale problems. Lieutenant Erik Peterson stated that “softball was a lifesaver for our troops in England.”6

The Canadians arriving in Britain during the winter of 1939-40 had an older generation of Britons recalling their sporting escapades from the previous war. It was assumed that Canadian military baseball would again be played. The Daily Mirror noted that qualified opponents would be needed, and so “men of the RAF … are to spend their winter evenings studying the rules and tactics of baseball which will be played behind the lines in the spring.”7

British newspapers also reacted with great excitement (and some sarcasm) to the introduction by Canadian troops of a new athletic pursuit. Under the headline “The Canadians Give Us a Brand New Game,” The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News provided detailed instructions on how to play softball, “first cousin to baseball,” and pointed out that both soldiers and schoolboys would find the game enjoyable. Softball was presented as a lighter, less serious version of baseball, wherein the pitcher was encouraged to “adopt any attitude he pleases in an attempt to bamboozle the batsman.”8

As training continued and fighting remained elusive, Canadian soldiers stationed at Aldershot took to holding public exhibitions and clinics for softball-curious locals. “Crowd See Softball for First Time in Their Lives,” exclaimed the Worthing Gazette. “They came, they saw, they listened, and at the end of the hour and ten minutes, the Canadians were hoping they were beginning to understand the game. The rules are really not so complicated as the Canadians imagine, but to the majority gathered at the Farm Recreation Ground on Saturday, softball needed some explaining.”9

More than 330,000 Canadian troops passed through Aldershot for training before being deployed across the United Kingdom. From the autumn of 1941 until early 1944 the defense of the UK, and particularly the Sussex coast, was in the hands of the 1st Canadian Army. This was the largest force of British Commonwealth troops ever to be quartered in the UK at one time.10 Playing baseball, and reeducating the locals on the finer points of the game, was not an uncommon duty for Canadian soldiers.

On August 23, 1940, two teams of Canadian soldiers, one representing Montréal and the other Hamilton, played a game at the East Surrey Sports Ground in order to raise money for the building of Spitfire airplanes. The Mirror and County Post wrote that “before the game commenced the rules were explained. During its progress spectators found Canadian soldiers ready with further explanations and descriptions of how in Canada, crowds of 75,000 shower pop’ bottles on the pitch when disgusted with the umpire.”11 The team of soldiers from Montréal defeated their Hamiltonian rivals by a score of 18-16.

The reporter also noted that one of the Canadians “displayed a real baseball cap” and that the crowd found its greatest amusement when the umpire “received a blow on the shin and hopped laboriously, rubbing it for all he was worth.”12

Two months later in Tadworth, England, a team of Canadian Highlanders played against a team of British Home Guards in a baseball match whose proceeds were donated to the war effort. The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News provided images of the Highlanders “coaching” their opponents and educating curious locals before the game.13 Dick Fowler, the Toronto-born Philadelphia Athletics pitcher who would return from service and throw a no-hitter against the St. Louis Browns, was serving with these same Highlanders.14 Fowler was not present, however, serving entirely in Canada because of chronic sinus issues.

During their down time, Canadian soldiers were permitted to join existing British baseball teams near their various barracks.15 The DeHavilland Comets, the Standard Telephone and Cable squad, and the Ford Motor Company team all employed the services of one talented amateur ringer named Pete Giovanella from Kirkland Lake, Ontario. The Comets even featured Philadelphia Athletics star Phil Marchildon for a few games. After joining the Royal Canadian Air Force, Marchildon surprised unsuspecting opponents with major-league fastballs before they “could even get the bats off their shoulders.”16

Marchildon was joined in the RCAF by Joe Krakauskas of the Washington Senators and Cleveland Indians, while the Boston Braves’ Roland Gladu joined the Canadian army. It appears that both Krakauskas and Gladu played only recreationally. A separate Midlands Baseball League, an existing federation of British ballclubs representing manufacturing plants, invited visiting armies to field their own sides. The league featured a Canadian Army nine and saw United States military teams join later in the war.17 The Canadian Army team went all the way to the Midlands World Series before losing the final, 13-0, to a team representing the US Army 10th Replacement Depot.18

Back home, as Canadians became accustomed to rations and recruiting posters, a ballpark became home to an entire exiled air force. Maple Leaf Stadium had been built in 1926 along Lake Shore Boulevard in Toronto in order to serve as a mainland home for the previously island-dwelling Toronto Maple Leafs. The ballpark eventually hosted an assortment of wartime fundraising events, from film screenings, to “follies” shows to boxing matches and ballgames.

The center-field wall at Maple Leaf Stadium was separated from Lake Ontario by only about 230 meters of open, undeveloped grassland. The airstrips of the Toronto Flying Club stood another 130 meters across a narrow channel of water on Toronto Island. That open space between the ballpark and the airfield would prove invaluable to a small Scandinavian nation that was about to encounter the blitzkrieg.

After the fall of Norway to the Nazis in June of 1940, General Otto Ruge of the Norwegian Army Air Force ordered the evacuation of as many air force personnel as possible. Ideally, they were to take as many aircraft and materiel as they could to a European location. With the fall of France and Nazi occupation of Norway, this became impossible. No aircraft were smuggled out, but 120 members of the air force escaped to Britain and awaited further instruction.

Negotiations between the governments of Canada and Norway concluded on September 7, 1940. The 120 officers and men came to Toronto, made use of the Toronto Flying Club on Toronto Island, and were housed in the open field beyond the center-field wall of Maple Leaf Stadium. Eventually, 17 buildings were constructed around, and in some cases touching, the outfield walls of the ballpark. The Toronto Flying Club turned over its airport and training aircraft to the Norwegians. The Norwegian airmen lived in the shadow of the ballpark in an area that is still known as “Little Norway.”

While stationed near the outfield fence, the Norwegian Army Air Force concocted a plan to acquire aircraft. Norway had purchased combat planes from the United States before the war. The planes had not yet been delivered. Technically, those planes now belonged to the occupying German forces. Yet, the neutral United States covertly sent $20 million worth of those airplanes to the airport next to Maple Leaf Stadium. The planes consisted of Fairchild PT-19 elementary trainers, Curtiss fighters, Douglas attack bombers, and Northrop patrol seaplanes. The Norwegians then launched a “Wings for Norway” fundraising campaign, which included events at Maple Leafs games designed to draw donations from baseball fans. The campaign raised over $400,000.19

Eventually, the airmen of Maple Leaf Stadium flew to Iceland, where they patrolled the North Atlantic for the remainder of the war. These same Norwegian fliers then escorted and assisted Canadian troops during the Dieppe raid, the Normandy landings, and the liberation of Holland.20

In the European Theater, the Canadian missionaries continued their campaign of baseball reeducation. On May 28, 1941, General Andrew McNaughton, commander-in-chief of the Canadian overseas forces, explained the game of baseball to Princess Mary, the sister of King George VI, and assembled British soldiers during an intrasquad game played between members of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals at a military hospital near London.21

Canadian troops “learning of the mediocre success which attended the introduction of baseball into this country, were hopeful that their exhibition games would help to further popularize it.”22 At the Braunton Road Grounds, the game was described as “a development of rounders, with which we were familiar in our youthful days, but it has evolved into a vehicle for the display of astonishing skill of which accurate catching and fielding are prominent features.”23 In August, near Burgess Hill, the Queen’s Own Rifles made use of a public address system while they played a game against the 12th Field Regiment. A Major Sutherland served as play-by-play man to “explain the game to spectators and give running commentary of the play.”24

In between adventures both playing and teaching baseball, soldiers were of course trained in Britain as they awaited deployment to Nazi-occupied Europe. The Canadian government encouraged sport as a way to toughen men for their coming crucible. “Senior officers plan to get them into shape for expected combat in the spring and aren’t wasting any time,” wrote the Globe and Mail. “They’re being hardened up physically by calisthenics and baseball.”25 The game continued to be a preferred pastime for soldiers as well as a valuable method of maintaining corps readiness for commanders. “There is a strong and reciprocal historical relationship between sports and the military,” wrote John Maker. He explained that softball was among the sports that also helped bridge the cultural divide within the Canadian forces:

“In Canada at the beginning of the Second World War, sports positively reflected the nation’s cultural desires and pastimes. These patterns were reflected in the army overseas. In the army, some sports were differentiated according to English and French-Canadian cultural preferences … however, troops representing both language groups professed a keen interest in hockey, softball and skating. These sports occupied a space of cultural consensus between English- and French-speaking Canadians overseas and differentiated them both from the British.”26

The temporary Canadian annexation of the hallowed grass inside Lord’s Cricket Ground literally had headlines screaming. “Egad! Most Extraordinary! What! BASEBALL at Lord’s?”27 bellowed the Associated Press on May 10, 1941. Canadian newspapermen (some of whom had watched soldiers play baseball at Lord’s multiple times during the First World War) defeated their still neutral American counterparts using “the sacred sod for a baseball game.”28

Of course, the United States did not remain neutral for long. With the arrival of American soldiers in Britain in 1942, the number and quality of baseball games being played increased rapidly. The London International Baseball League was created as a recreational league for Canadian and American troops stationed around the British capital. The league provided a way to organize and structure the thousands of soldiers playing informal forms of baseball across Britain. It also provided relief from the inaction and tedium that affected many men as they impatiently awaited the invasion of Europe.

The London International Baseball League consisted of eight military teams, two of which were Canadian. The league staged its championship games at the legendary Stamford Bridge Stadium, home to the Chelsea Football Club. The most competitive teams in the league were the US 660th Engineers, the US 827th Signal Battalion Monarchs, the 1st Canadian General Hospital, and the team representing the Canadian Military Headquarters. The 1st CGH team featured Leo Curtis of Orange, Massachusetts. Curtis, an accomplished semipro pitcher, joined the Canadian Forces at the outbreak of the war and played for 1st CGH during his entire stint in the army.29 Curtis led his hospital team into the LIBL championship on June 25 and 28,1943. The Canadian team was swept two games to none by the Signal Monarchs.

With so many North American baseball players in action, a series of international friendlies was scheduled between Canadian and American baseball teams. Three games in particular were promoted and covered as all-star, all-soldier affairs. These games pitted the best enlisted baseball players against each other in a best-of-three series. Game one was held on July 4, 1942, before 6,000 fans at Selhurst Park in London, home to the Crystal Palace Football Club. The United States Army Air Force all-stars triumphed over the Canadian Army all-stars in a “home run fest,”30 19-17.

The second game of the series took place on August 3 at Wembley Stadium and featured another crowd of around 6,000 spectators. The Canadian Army Headquarters team defeated the American Army Headquarters squad, 5-3. Lady Clementine Churchill, wife of the British prime minister, was in attendance and met with both teams during a pregame ceremony. The game raised nearly $4,000 for the British Red Cross. The rubber match for the North American neighbors would take place on August 22 at the Memorial Sports Ground in Red Hill. After falling behind early, the Canadians roared back and won the game and the series on the first of Ed Smith’s heroic walk-offs described above.

At least 11 other Canada vs USA all-star baseball games were staged, usually for the purposes of raising charitable or war funds. Though they didn’t always garner the attention of the three-game series in 1942, the games continued to be a significant draw across the UK. In the early summer of 1943, the Royal Canadian Air Force was defeated by the United States Army Air Force, 7-2, in Sutton, Surrey. Some 5,000 fans were in attendance.31

On June 6, 1943, at Hounslow Cricket Ground near London, a “Return Challenge Match” was promoted to assist the British Red Cross and the St. John Prisoners of War Fund.32 No score is known. On August 7, 1943, a softball game between the US and Canadian armies served as the preliminary attraction at Wembley Stadium before an advertised “all professional” baseball game between the US Air and Ground Forces. A total of 21,500 paying customers saw both games and supported the Red Cross. It was the largest crowd to see baseball in Britain since the First World War.33

The Canadian softball team featured Ed Smith of Kingston, Don Price and Pete Giovanella of Kirkland Lake, Al Fleming of Halifax, and transplanted Canadian Leo Curtis of Orange, Massachusetts. The US “pro” baseball teams featured Joe Rundus, formerly of the Brooklyn Dodgers organization, New York Giants farmhand Pete Pavich, Paul Campbell of the Boston Red Sox, Louis Thuman of the Washington Senators, Ralph Ifft of the New York Yankees system, Stan Stuka of the Boston Braves and Philadelphia Phillies organizations, Richard Catalano of the St. Louis Cardinals system, and coach Monte Weaver, a former Washington Senators pitcher.

June 3, 1944, featured the most dramatic Canada vs. USA baseball game, when Ed Smith hit his walk-off grand slam at Wembley Stadium. Smith remained in the Canadian Army after the war and eventually retired to Florida.34 A few days after the Wembley game, mere hours before the D-Day landings of Operation Overlord, another international friendly was organized south of London in Sevenoaks. The Chronicle noted:

“A surprise tea, organized by Dr. and Mrs. Spon, was held at the Post Office on Wednesday. Following this, the address by Col. Ponsonby attracted a large crowd to the Green, where they later saw a baseball match between Canadian and American teams. The Canadians won by 5 runs to 2. Capt. Harrington, U.S. Army, provided a running commentary.”35

As the war continued, so too did the great game. Baseball games were staged in Shoreham, England, while Canadian troops prepared for their ill-fated raid on Dieppe. On October 16, 1943, the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa were observed playing baseball outside Hursley Camp. They were defeated by a team of soldiers from Toronto by a score of 13-3.36 The Torontonians were observed by members of the Queen’s Own Rifles and may have been Conn Smythe’s 30th Battery. Smythe, the hockey impresario who had served with the Canadian Army during the First World War, recruited his own group of sportsmen-soldiers while training officers in Toronto.

Toronto Argonauts football stars Ted Reeve and Shanty McKenzie joined up to fight and play with Major Smythe. Eventually, the men of the 30th Battery were incorporated into the 7th Toronto Regiment. They were first stationed in Victoria and then later shipped to the UK, where they spent months training and hosting softball games. Smythe’s 30th Battery Bombers challenged locals to various sporting events, including baseball and softball, throughout their service in both Europe and the UK.

In 1944 they were tasked with taking Caen, France, an action Smythe nearly missed due to a softball injury. In the days after the successful D-Day landings, Smythe organized a softball tournament in Caen. He played third base and claimed, in his autobiography, to have been visited by Winston Churchill after a game.37

Elsewhere in the European Theater, baseball found a way. Italy’s national baseball program credits the introduction of the game there to the contests played between American and Canadian occupying armies.38 When soldiers in Italy were moved out in order to join the First Canadian Army in the fight to liberate the Netherlands, they brought baseball along with them. The Liverpool Daily Post reported on April 2, 1945, that German resistance had cracked. There was “carnage on the roads as Germans race out of Holland.”39 A reporter embedded with the Canadian forces wrote that “German artillery fire has slackened considerably, and on the west bank of the Rhine, north of Cleve, Canadian soldiers are playing baseball where just days ago German shells were falling.”40

To celebrate the German defeat, the Regina Rifles played softball near Rotterdam against a team of female Canadian Armed Forces personnel calling themselves the “Eager Beavers.”41 After the conclusion of the European war, a Canadian Armed Forces Softball Championship was organized in Utrecht. Some of the same teams that competed in the Canadian Army Baseball League took part. On October 3, 1945, the Queen’s Own Rifles defeated 2 Canadian General Reinforcement Unit 3-0 to take the championship.42 The Canadian Army remained in Holland and Belgium after the war and played a great deal of softball. Gary Bedingfield’s Baseball in World War II Europe provided details:

“On the continent, softball was the main game of Canadian servicemen. The Conn Smythe 30th Battery Bombers in Belgium set all kinds of records with 110 wins in 114 games. The 2nd Canadian Advanced Base Workshop team settled for a draw after 18 scoreless innings against an American service team in Antwerp. Baseball did also occur on the continent in the form of exhibition games. On September 6, 1945, the powerful U.S. Army 29th Infantry Division team defeated the 2nd Canadian Division All-Stars, 5-0, before a crowd of 8,000 at Soesterberg Airfield in Holland. But Canadian servicemen were not limited to bringing baseball to Europe. Wing Commander G.N. Parrish of Listowel, Ontario, introduced the game to India. ‘I found a dozen Canadians on the squadron willing to play,’ the Simcoe Reformer reported on June 15, 1944, ‘and I persuaded even Australians and British crews’ to play baseball.”43

The merciful end of the war did not mean the end of competitive baseball for Canadian soldiers in Britain. On June 26, 1945, the Canadian Army England Sports Committee of the Auxiliary Services, under the chairmanship of Brigadier J.E. Sager, announced an extensive summer of sports. “For five years we have been conditioning these men for war. Now we’ve got to condition them in how to live, how to relax and enjoy themselves,” explained Sager. “All personnel of the Canadian Army are encouraged to compete.”44

The new Canadian league would feature 14 teams of soldiers, playing between 14 and 16 games each, in various locations around southeastern England during the summer of 1945. The season was kicked off with a special exhibition game played between the 1st Canadian Central Ordinance Depot and a visiting team from the United States Army Air Force. Some 1,500 Canadian and American soldiers watched the game on what was billed as “North American Day” at Peper Harrow in Surrey. The Americans won the game 2-0.

On July 13 another visiting team of American airmen challenged the 1st Central Ordinance Depot. En route to their own 2-0 victory, the Canadians turned the only recorded wartime triple play. With the bases loaded in the fourth, American batter Bob Froelich hit a line drive to Canadian third baseman Johnny Sefton. Sefton caught the drive for the first out, stepped on the bag before the runner could scramble back for the second, and then threw to first baseman Tommy Marshall for the third.45

For the duration, baseball players were willingly exploited as fundraisers. Teams of soldiers played in aid of “Wings for Victory,” a National Savings campaign designed to build warplanes. The campaign was staged in almost every city, town, and village, and baseball became an integral part of the proceedings.46 Canadian soldiers played baseball in Storrington during March of 1942 in order to drive dollars “towards the aim of £120,000, the cost of a new corvette.”47 An August 22, 1942, game between Canada and the USA in Surrey was a fundraiser for the “Tanks for Attack” fund.48

“Holidays at Home” was a series of fundraising and morale-boosting events staged by communities in Britain. A week of entertainment was held for civilians who due to the war and gasoline rationing were unable to travel or enjoy any kind of vacation.49 Baseball games were almost always a part of these festivities. On May 22, 1943, a game was played at Giant Axe stadium, home to the Lancaster Football Club. It featured “teams representing the United States and Canada.”50

Local attendees were promised that a Lancaster bomber would also be on hand. Those interested could purchase stamps and then place them on a bomb that would be later dropped on Germany.51 In 1943 alone, the fundraising efforts of Canadian and American ballplaying soldiers raised an estimated $344,000 (US). Adjusted for inflation, that’s over $5.5 million in 2021 Canadian dollars.

The following year, service teams supported the “Salute the Soldier” campaign all over Britain. Canadian, American, and British airmen took part in a softball and baseball exhibition in Darlington on May 26, 1944. Monies raised went toward the Mayor of Darlington’s War Fund.52 When American and Canadian forces left Britain at the end of 1945, their baseball playing had contributed to wartime fundraising in a significant way.53

After the disaster at Dieppe, where 3,367 Canadians were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner, Canadian baseball found its way into prisoner-of-war camps. Interviewed from a German POW camp, Toronto soldier Carl Scott was happy to see the arrival of Canadian newspapers in the Young Men’s Christian Association aid packages sent from home. Under the headline “He Wanted Baseball News,” Scott was quoted politely dismissing the field reporter visiting the camp by saying, “Excuse me while I see how the Leafs are doing.”54 The Belfast News-Letter reported that the YMCA had started sending baseball equipment into the POW camps where the Dieppe raiders were being held. The equipment was coming “especially from Canada.”55

R.P. Hall of the Royal Rifles was imprisoned in Stalag 9C. “He reported the Canadian prisoners there were all of good heart and were playing baseball.”56 Stalags (German slang for prison camps) were a common site for Canadian military baseball during the war. Captured soldiers often played the game under the supervision of their Nazi captors. Private Taylor wrote to his mother from Stalag 4B and told her of his participation in baseball games.57

The distinction of being the best-known baseball-playing POW belongs to Phil Marchildon. After the conclusion of the 1942 major-league baseball season, Marchildon joined the RCAF and refused an opportunity to stay in Canada, saying he did not want special treatment. Marchildon was assigned to a seven-man Halifax bomber crew. On the crew’s 26th mission, they were shot down over northern Germany on August 17, 1944. Marchildon was sent to Stalag Luft III, a prison camp for airmen:

“Some of the better German Prisoner Of War camps were known to have had multiple leagues operating. In Stalag Luft III, during the peak summer of 1944, there were probably 200 baseball teams active. This is an astonishing number, especially considering that the 1943-44 off-season at Stalag Luft III had been considerably disrupted by the Great Escape.”58

Marchildon did not speak often or reminisce about his time in a Nazi prison camp. While imprisoned, he was fed a diet of watered-down soup and bread mixed with sawdust. He was liberated by British soldiers on May 2, 1945.59 He spent nine months in captivity and remains Canadian baseball’s greatest war hero. He returned to the majors, but displayed the nightmares and physical ailments that we would today consider symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder.60

Between training, action, rest, and relaxation, some Canadians spent more than five years in the UK. Some married, many more had partners, and some 22,000 British children were born to Canadian fathers. As they lived their lives overseas, Canadian soldiers played ball at more than 60 known locations in Britain, from Greenock to Torquay and most bases, parks, and stadiums in between.

On the European continent, as Canadian armies pushed forward through Italy and the Netherlands, baseball games were played. Records are scarce of baseball being played in India and Hong Kong, in Merchant Marine shipyards, or on the airfields of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Yet given the overwhelming amount of baseball played by enlisted men in the better documented theaters of war, including in captivity, it is very likely that baseball was played everywhere the Canadians went during the Second World War. Upon returning to Canada, many soldiers spoke fondly of the baseball games they played, and of course, continued watching and playing the game back home.61

Nineteen Canadians associated with amateur or semiprofessional baseball lost their lives during the Second World War. They were Don Stewart, Liston Anderson, George Atkinson, Roger Carroll, George Dean, Thornton Doig, Robert Dubeau, Harold German, Herman Jonasson, Arthur Judges, Mike Moroz, Don Norton, Con Radocy, Stan Reid, Don Ross, Basil Smith, Albin Sumara, Charles Weatherby, and Mike Zima.62

STEPHEN DAME is a middle school teacher of Humanities in Toronto. He is a member of the Hanlan’s Point chapter of SABR. Stephen regularly presents research papers at the annual conference organized by the Centre for Canadian Baseball Research. He has researched military baseball during Canada’s World War efforts, and explored the links between baseball and the prime ministers of Canada.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to give special thanks and appreciation to Gary Bedingfield, William Humber, and Andrew North. Mr. Bedingfield’s research into the story of Canadian baseball players in wartime, chronicled in his book Baseball in World War Two Europe, was an invaluable source for this project. The incredible and rare photographs he unearthed also helped illustrate a presentation of this paper for the Centre for Canadian Baseball Research. This project stands on the shoulders of Mr. Bedingfield’s work. Mr. Humber, Canada’s pioneering and foremost baseball historian, was incredibly generous with his time, resources, and advice. He personally made me feel welcome in the world of baseball historians and their research. Mr. North, founder of the Centre for Canadian Baseball Research and organizer of its annual history conference, gave me a platform to present my initial research and the confidence and encouragement necessary to continue forward. I am grateful to all three gentlemen.

John Thorn and Jim Leeke, who are two of the very best baseball historians and authors, were also available, supportive, and helpful to me during this project.

Notes

1 “Canadians Rally to Win Rubber,” Surrey Mirror and County Post, August 28, 1942: 2.

2 Gary Bedingfield, Baseball In World War Two Europe (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 1999), 89.

3 Bedingfield, 100.

4 “War Diaries 1940,” The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada Regimental Museum and Archive, last modified February 5, 2021, https://qormuseum.org/history/timeline-1925-1949/the-second-world-war/war-diaries-1940/.

5 John Maker, “Sports and War- A Winning Combination,” Laurier Centre for Military, Strategic and Disarmament Studies – Wilfrid Laurier University, last modified March 13, 2011, https://canadianmilitaryhistory.ca/sports-and-war-a-winning-combination-by-john-maker/.

6 Bedingfield, 5.

7 “Sports Notes,” Daily Mirror (London), September 13, 1939: 8.

8 “The Canadians Give Us a Brand New Game,” Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (London), April 12, 1940: 50.

9 “Crowd See Softball for First Time in Their Lives,” Worthing Gazette (Worthing, Sussex, England), December 17, 1941: 22.

10 “History of Canadians Stationed in the U.K.,” Canadian Roots U.K., last modified 2016, http://www.canadian-rootsuk.org/historycanadiansuk.html.

11 “Baseball Match Aids Fund,” Surrey Mirror and County Post (Reigate, Surrey, England), August 23, 1940: 5.

12 “Baseball Match Aids Fund.”

13 “A Baseball Match,” Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, October 25, 1940: 23.

14 William Humber, Diamonds of the North (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1995), 161.

15 Bedingfield, 87.

16 Bedingfield, 88.

17 Bedingfield, 44.

18 Bedingfield, 51.

19 Geoff Ward, “Little Norway,” WWII Norge, last modified 2021, https://www.wwiinorge.com/notes/little-norway/.

20 Ward.

21 “Princess Royal Watches Canadian Troops Playing Baseball,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), May 29, 1941: 13.

22 “New World Baseball in Manchester,” Manchester Evening News (Manchester, United Kingdom), August 13, 1942: 5.

23 “Savings for Victory,” North Devon Journal (Barnstable, North Devon, United Kingdom), May 20, 1943; 4.

24 “War Diaries 1941,” The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada Regimental Museum and Archive, last modified February 5, 2021, https://qormuseum.org/history/timeline-1925-1949/the-second-world-war/war-diaries-1941/.

25 Ross Munro, “Sports Toughen Canadians for Expected Spring Battle,” Globe and Mail, March 16, 1941: 22.

26 John Maker,”SportsandWar-A Winning Combination,” Laurier Centre for Military, Strategic and Disarmament Studies – Wilfrid Laurier University, last modified March 13, 2011, https://canadianmilitaryhistory.ca/sports-and-war-a-winning-combination-by-john-maker/.

27 Eddie Gilmore, “Egad! Most Extraordinary! What! BASEBALL at Lord’s?” Globe and Mail, May 10, 1941: 16.

28 Gilmore.

29 Bedingfield, 87.

30 Bedingfield, 87.

31 “Sports Shorts From Britain,” Globe and Mail, August 9, 1943:16.

32 “Baseball,” Middlesex Chronicle (Hounslow, London, England), May 22, 1943: 5.

33 Bedingfield, 74.

34 Bedingfield, 89.

35 “A Surprise Tea,” Sevenoaks Chronicle and Kentish Advertiser (Sevenoaks, Kent, England), June 9, 1944: 9.

36 “War Diaries 1943,” The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada Regimental Museum and Archive, last modified February 5, 2021, https://qormuseum.org/history/timeline-1925-1949/the-second-world-war/war-diaries-1943/.

37 Conn Smythe and Scott Young, Conn Smythe: If You Can’t Beat ‘Em in the Alley (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1981).

38 “History of Baseball in Europe,” Baseball-Reference.com, last modified September 16, 2014, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/History_of_baseball_in_Europe.

39 “German Resistance Cracks in the West,” Liverpool Daily Post, April 2, 1945:1.

40 “Baseball Now,” Liverpool Daily Post, April 2, 1945: 1.

41 Humber, 10.

42 Gary Bedingfield, “Canuck Baseball,” Baseball in Wartime, last modified April 26, 2008. http://www.baseballinwartime.com/canuck.htm.

43 Bedingfield, “Canuck Baseball.”

44 Bedingfield, “Canuck Baseball.”

45 Bedingfield, “Canuck Baseball.”

46 Bedingfield, 101.

47 “Baseball Match,” Worthing Gazette, March 11, 1942: 6.

48 “Tanks for Attack,” Surrey Mirror, August 7, 1942: 2.

49 Bedingfield, 101.

50 ” Tomorrow’s Parade,” Lancaster Guardian (Morecambe, Lancashire, England), May 21, 1943: 5.

51 “Tomorrow’s Parade.”

52 “Darlington Baseball,” Newcastle Journal (Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear, England), May 25, 1944: 3.

53 Bedingfield, 102.

54 Douglas Amaron, “Were Waiting for Us Say Wounded Canucks,” Globe and Mail, August 22, 1942: 7.

55 “A Pep Talk,” Belfast News-Letter, June 12, 1942: 3.

56 “Prisoners in Good Heart,” Globe and Mail, November 29, 1943:15.

57 “Baseball in Stalag,” Globe and Mail, October 12, 1944: 4.

58 Daniel Gabriel, “Baseball Behind Barbed Wire,” Elysian Fields Quarterly, last modified 2002, http://www.efqre-view.com/NewFiles/v19n2/books-baseballbarbedwire.html.

59 Kevin Glew, “Remembering Phil Marchildon, Canadian Pitching Ace and War Hero,” Canadian Baseball Network, last modified November 11, 2020, https://www.canadianbaseballnetwork.com/canadian-base-ball-network-articles/remembering-phil-marchildon-canadian-pitching-ace-and-war-hero.

60 Glew.

61 Kelly Anne Griffin, “From Humble Beginnings to Making History in Montréal,” The Discover Blog, last modified March 20, 2018, https://thediscoverblog.com/2018/03/20/from-humble-beginnings-to-making-history-in-Montréal/.

62 Gary Bedingfield, “Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice,” Baseball in Wartime, last modified March, 2021, https://www.baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com/table_of_all_players.html.