A Sleeping Giant: Detroit in the Mid-1930s

This article was written by Gary Gillette

This article was published in 1935 Detroit Tigers essays

In the decade of the 1930s, Detroit was a city uneasily poised between the Paris of the West of the 1920s and the Arsenal of Democracy of the 1940s. Auto industry titans like Henry Ford, the Dodge Brothers, the Fisher Brothers, Alfred Sloan, and Walter Chrysler had built a powerful industrial engine, but that engine was mostly idling, awaiting a return to prosperity. In the decade of the 1930s, Detroit was a city uneasily poised between the Paris of the West of the 1920s and the Arsenal of Democracy of the 1940s. Auto industry titans like Henry Ford, the Dodge Brothers, the Fisher Brothers, Alfred Sloan, and Walter Chrysler had built a powerful industrial engine, but that engine was mostly idling, awaiting a return to prosperity.

In the decade of the 1930s, Detroit was a city uneasily poised between the Paris of the West of the 1920s and the Arsenal of Democracy of the 1940s. Auto industry titans like Henry Ford, the Dodge Brothers, the Fisher Brothers, Alfred Sloan, and Walter Chrysler had built a powerful industrial engine, but that engine was mostly idling, awaiting a return to prosperity.

The entrepreneurial drive, innovation, and investment that had fueled the city’s meteoric growth had stalled in the Great Depression. While a disaster for Americans nationwide, the Depression manifested itself in an especially savage way in Detroit, where hundreds of thousands subsisted meagerly “on relief.” Poor and out-of-work Detroiters were literally starving to death by the early 1930s, providing the impetus for the famous and bloody Ford Hunger March of March 7, 1932. On that day, several thousand demonstrators – many of them unemployed Ford workers –marched on the Rouge Plant in Dearborn, where police and company security personnel opened fire without warning, killing five and wounding more than 50.

Detroit’s population rose from less than 300,000 in 1900, 13th in the US, to almost 1.6 million in 1930. The fourth largest city in the country, Detroit grew by 58 percent in the 1920s. It saw a slight population decline in the early 1930s, but recovered to register a 3.5 percent growth rate in that decade. The suburban migration of the white middle class had already begun, as the population of Detroit’s suburbs grew by almost 20 percent in the 1930s.

Geographically, the city reached its full extent with the large annexations that filled out the Northwest and Northeast quadrants of Detroit from 1921 to 1926, when a change in Michigan law effectively ended the city’s territorial expansion. Housing development in Northeast and Northwest Detroit would have to wait till the late 1940s, however, when the great postwar expansion filled those sections of the city with mile after mile of inexpensive single-family homes.

While there were a handful of other companies making cars, the Big Three that would dominate the auto business for the rest of the century were already in place. General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler were selling almost 90 percent of new cars in the US, and their power and influence in Wayne County and across the state of Michigan cannot be overstated.

Considered a leader in public transportation, Detroit was the first city in the US to own its municipal transit system. Despite its nickname, the Motor City maintained a network of trolleys traversing the city and reaching far into the suburbs. The Detroit Street Railway system peaked at 466 route-miles in 1934; meanwhile, other Michigan cities were retiring their trolleys in favor of buses. Interurban trolleys ran from Detroit to Flint, Ann Arbor, Kalamazoo, Lansing, Grand Rapids, Port Huron, and Toledo.

Detroit’s international connections to the city of Windsor and the province of Ontario across the Detroit River to the south were the same then as now. The recently completed Ambassador Bridge – the longest suspension bridge in the world when it opened – and the Detroit-Windsor vehicle tunnel, plus an older rail tunnel and a ferry, carried commercial and passenger traffic to and from Canada.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s election as president in 1932 resulted in a series of new federal programs that partly ameliorated the depressed US economy. The Civilian Conservation Corps began in 1933. The groundbreaking Social Security Act of 1935 established unemployment compensation, aid to dependent children, and maternal and child welfare programs.

The general national recovery was also felt in Michigan in 1935, with personal income up from its 1933 nadir. Car production, which had exceeded 5 million units in 1929 before plunging by about two-thirds by 1932, was quickly ramping back up. In 1937 auto production was three times the depressed level of five years earlier.

Another seminal piece of federal legislation that had a major impact on Detroit was the 1935 Wagner Act, which led to the establishment of powerful industrial trade unions. The formation of the United Auto Workers in August 1935 and the resulting unionization of the auto industry in the late 1930s and early 1940s led to a rise in the standard of living that made Detroit’s middle class the envy of the world in the postwar era.

Along with thousands of ethnic whites from Eastern and Southern Europe and from Appalachia, tens of thousands of African Americans had migrated to Detroit from the rural South to find work in the factories during World War I and the Roaring Twenties. Detroit’s black population surged from about 5,000 in 1910 to about 120,000 in 1930 (approximately 8 percent of the city). Henry Ford gave good-paying jobs to thousands of black men at Ford Motor’s massive Rouge Factory complex in Dearborn, enabling a substantial black middle class to grow in Detroit. A self-contained industrial city of 1,300 acres that could turn raw materials into a finished automobile in 28 hours, “The Rouge” employed almost 100,000 at its peak.

The racial discrimination that would spark major riots in 1943 and 1967 was already deeply rooted in the Detroit area. Some people fought back, as when white and black Hamtramck High School students joined together to protest segregation in school activities in 1935. The Detroit chapter of the NAACP was, then as now, the influential civil rights organization’s largest, and the UAW would quickly become a major progressive force. Tragically, though, it was the legacy of ongoing racial tension that in many ways defined Detroit during the 20th century, epitomized by the 1925 Ossian Sweet murder trial, made famous by the 2004 book Arc of Justice.

The city’s architectural landscape in the 1930s was dotted with skyscrapers well-known to many generations of Detroiters – among them the Penobscot Building, the Union Trust (later Guardian) Building, and the Book Cadillac Hotel – all erected in the 1920s. Along with the Fisher Building, the Guardian and Penobscot remain today as fine examples of Art Deco architecture.

Despite the multitude of skyscrapers erected in Detroit in the 1920s, the city’s downtown was already in decline, both physically and economically. Retailing was dominated by J.L. Hudson’s enormous department store at Woodward and Gratiot, along with Crowley’s and Kern’s department stores one block away. The city’s share of metropolitan-area jobs in the manufacturing sector dropped by 23 percent from 1929 to 1939, and Detroit’s share of area employment in the retail and wholesale sectors was also dropping.

Planning had already begun in the mid-1930s to build the large housing projects that would later become infamous, although all of that public housing was then segregated and mostly reserved for whites. The crowded African-American neighborhoods of Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, where black citizens were ghettoized on the east side of the central business district, were considered slums by the white power structure. Both historic black areas were leveled under the guise of urban renewal after World War II.

The biggest physical difference between 1930s Detroit and the postwar city was the riverfront. Before World War II, valuable riverfront land was not used for civic purposes or for public recreation as later. Instead, the blocks adjacent to the Detroit River were occupied by industry and commerce, plus the railroads and ships needed to move goods to and from the plants.

The “civic center” of prewar Detroit was well north of the river, just south of the retail district. City Hall was an 1871 sandstone structure, a mishmash of Italianate, French, and Georgian elements located on the west side of Woodward Avenue on what would become Kennedy Square in the 1960s and Campus Martius four decades later. County offices were housed in the 1902 baroque Wayne County Building, east of City Hall across Cadillac Square. City Hall moved to the riverfront in the early 1950s; the County Building still stood in 2014 but was empty.

Anchored by General Motors’ massive headquarters and the gilt-topped Fisher Building – both designed by world-famous architect Albert Kahn – the New Center business district along West Grand Boulevard (just west of Woodward) was still new in the early 1930s. Just south of New Center, the twin jewels of Detroit’s Cultural Center – the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) and the Detroit Public Library – were built along Woodward Avenue, directly across from each other, in the 1920s. Diego Rivera’s world-famous murals generated intense local controversy along with worldwide acclaim when unveiled at the DIA in 1932.

Between the downtown business district and New Center, another major player was just getting organized. Over the years, it would become known as Detroit’s Midtown. In 1934 the recently amalgamated Colleges of the City of Detroit were renamed Wayne University. Wayne would add a School of Public Affairs and Social Work in 1935 and gain its Law School two years later. It did not become Wayne State University until 1956.

Detroit’s media scene in the 1930s was dominated by the ink-stained wretches who wrote, printed, and distributed the city’s three major daily newspapers: the conservative News, the liberal Free Press, and the now-defunct, then Hearst-owned Times. The Detroit Tribune, founded in 1933, covered the city’s growing African-American community, competing with the Michigan Chronicle, today’s foremost African-American paper, which began in 1936.

The print medium’s pre-eminence was being challenged by an electronic medium for the first time in the 1930s with radio’s rapid rise in popularity. Only half of Michigan households owned a radio set in 1930, but market penetration was almost universal by the end of that decade. The nationally famous radio drama The Lone Ranger originated from Detroit’s WXYZ, as did other national programs. Three other radio stations were on the air in Motown in 1934: WJR (which upped its broadcast signal to 50,000 watts in 1935), WWJ, and WMBC (later WJLB).

Republican Frank Couzens, son of former Mayor and then US Senator from Michigan James Couzens, was the as mayor of Detroit from 1934 to 1938. The city of Detroit had a mayor-council form of civic government that was dominated by a strong mayor and featured a weak city council. The mayor’s office had been controlled by Republicans since 1912, with only two Democratic mayors interrupting that string. One was popular Democrat Frank Murphy, who defeated former Mayor Charles Bowles after Bowles’ recall in 1930. Bowles was notable mostly for being the candidate of the Ku Klux Klan, which operated openly and counted thousands of members in Detroit in the 1920s and 1930s. Murphy later became governor of Michigan, attorney general of the United States, and an associate justice of the US Supreme Court.

The intense social and political unrest of the 1930s was fanned by Father Charles Coughlin, a radical populist dubbed the Radio Priest. Coughlin was initially a supporter of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, but later became very conservative and bitterly opposed FDR. Coughlin’s primary forum was his weekly radio show on WJR, the Hour of Power. Previously an unknown parish priest, Coughlin took to the new medium in 1926 to raise money to build the Shrine of the Little Flower in suburban Royal Oak.

At his height in the 1930s, Coughlin’s broadcasts from the Shrine commanded a national audience of 30 million or more listeners. He was initially carried on CBS, then later on a network of stations Coughlin himself put together. Coughlin’s popularity declined in the late 1930s as he became increasingly anti-Semitic and pro-fascist to the point of opposing US entry into World War II.

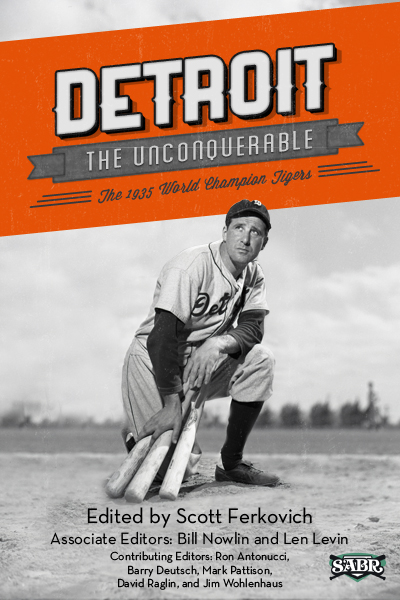

Sports provided a pleasant diversion from the life-and-death issues of the Great Depression, and baseball was the unchallenged king. “First in the affection of the city comes its baseball team,” concluded a 1940 history of the city, Detroit: Dynamic City. “No matter how seriously Detroiters may be divided among themselves otherwise, 99 percent of them stand solidly behind their beloved Tigers of the American League.”

A decade later, This Is Detroit, a pictorial history that was labeled as an “official publication of Detroit’s 250th birthday festival,” reiterated the status of the national pastime in the Motor City. The book featured only four images of prominent athletes: Charlie Bennett, Ty Cobb, Mickey Cochrane, and Joe Louis. Cobb and Cochrane were called “baseball immortals,” while Louis was unfairly called just a “former heavyweight champion.” The book included images of Recreation Park in 1886, where the National League Detroit Wolverines played, and of Tiger Stadium in 1940. Other sports mentioned included croquet, bicycle racing, boat racing, cricket, and ice skating – there was no mention of football, basketball, or hockey.

The Corktown neighborhood, where Navin Field was built in 1912, was an Irish working-class area. Several local landmarks familiar to later Tigers fans were present in the 1930s, including the Gaelic League on Michigan Avenue, Brooks Lumber on Trumbull, and the massive Beaux Arts Michigan Central railroad station on Vernor, a half-dozen blocks west of the ballpark.

Because of its large and prosperous black population, Detroit was considered a very desirable market by the businessmen who organized and ran the various Negro Leagues. Yet Detroit couldn’t sustain a successful Negro League team after 1931, when the Negro National League’s Detroit Stars had folded, along with the league.

After playing at Mack Park on Detroit’s East Side through 1929, the Stars moved to Hamtramck in 1930, just north of the huge Dodge Main factory complex. Stars owner John Roesink, a major promoter of semipro baseball in Detroit, built Hamtramck Stadium for the team in what is now Veterans Memorial Park. Roesink was a friend of Ty Cobb, and the Georgia Peach showed up to throw out the ceremonial first pitch at Hamtramck Stadium – a gesture that many might otherwise find incongruous. Turkey Stearnes, one of black baseball’s all-time top sluggers as well as the greatest African-American ballplayer in Detroit history, played for the Stars from 1923 through 1931 and in 1937.

The short-lived Negro East-West League and its Detroit Wolves played in Hamtramck in 1932, though both perished before midsummer. In 1933 the advent of the second Negro National League brought a new Detroit Stars club that survived only one season. In 1935 the Nashville Elite Giants were slated to move to Detroit, but were unable to secure a lease to play at Hamtramck Stadium. The Motor City would see one last major Negro League team in 1937, when the new Negro American League debuted with another Stars franchise in Hamtramck that again lasted for only a single summer.

In so-called Organized Baseball, the fading of the legends of the 1920s was also evident. The last legal spitball in the major leagues was thrown in September 1934 by Burleigh Grimes, who retired at the end of the season. Babe Ruth, who revolutionized the national pastime with his home run exploits in the early 1920s, retired at the end of May 1935.

In 1935 Detroit was beginning to awaken from its slumber. The prolonged nightmare of the Great Depression, however, wouldn’t end until the United States began seriously arming for World War II several years later. Malcolm Bingay, the Detroit sportswriter who would serve as managing editor of both the News and Free Press in his career, knew the city better than most and as well as anyone.

Bingay aptly called baseball “Detroit’s Safety Valve.”

Two bits of trivia:

-

On January 8, 1935, future Tigers infielder Reno Bertoia was born in Italy. Bertoia grew up in Windsor, became a bonus baby with the Tigers in 1953 along with Al Kaline, and spent most of his major-league career wearing the Old English D. After retiring, Bertoia was the longtime president of the Tigers players alumni association until his death in Windsor in 2011.

-

On February 3, 1935, future Tigers infielder and coach Dick Tracewski was born in northeastern Pennsylvania. Tracewski served as a utility infielder on the 1968 world championship team and was the first-base coach on Detroit’s 1984 championship squad.

GARY GILLETTE is editor of SABR’s annual “Emerald Guide to Baseball,” a member of Baseball Prospectus’s advisory board, and co-chair of SABR’s Ballparks Committee. Gillette has written, edited, or contributed to dozens of baseball books and websites, including ESPN.com and TotalBaseball.com. He was the editor of the “ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia,” executive editor of the “ESPN Pro Football Encyclopedia,” and a contributor to six editions of “Total Baseball.” As a director of the Tiger Stadium Conservancy since 2007, Gillette fought to save the historic stadium and continues to ght to save the field at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull in Detroit. As president of the Friends of Historic Hamtramck Stadium, he led the successful effort to place one of the few remaining Negro League ballparks on the National Register of Historic Places. Gillette lives in Detroit’s historic Indian Village, two doors away from the house built for Chalmers Motors president Hugh Chalmers in 1910.

Sources

Books

Babson, Steve, Working Detroit: The Making of a Union Town (New York: Adama Books, 1984).

Bates, Beth Tompkins, The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

Bingay, Malcolm W., Detroit Is My Own Home Town (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1946).

Boyle, Kevin, Arc of Justice: A Saga of Race, Civil Rights, and Murder in the Jazz Age (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2004).

Bryan, Ford R., Rouge: Pictured in Its Prime (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2003).

Darden, Joe T., Richard Child Hill, June Thomas, and Richard Thomas, Detroit: Race and Uneven Development (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1987).

Eichorn, George B., Detroit’s Sports Broadcasters On the Air (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2003).

Farley, Reynolds, Sheldon Danziger, and Harry J. Holzer, Detroit Divided (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2000).

Ferry, W. Hawkins, The Legacy of Albert Kahn (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1987).

Fogelman, Randall, Detroit’s New Center (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2004).

Gavrilovich, Peter, and Bill McGraw, eds., The Detroit Almanac: 300 Years of Life in the Motor City (Detroit: Detroit Free Press, 2000).

Gay, Cheri Y., Detroit Then and Now (San Diego: Thunder Bay Press, 2001).

Gillette, Gary, and Pete Palmer, The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia, fifth edition (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2008).

Kavanaugh, Kelli B., Detroit’s Michigan Central Station (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2001).

Lester, Larry, Sammy J. Miller, and Dick Clark, Black Baseball in Detroit (Chicago: Arcadia Publishing. 2000).

Linn, Andy, Emily Linn, and Rob Linn, eds., Belle Isle to 8 Mile: An Insider’s Guide to Detroit 2012, no publisher listed)

Meier, August, and Elliott Rudwick, Black Detroit and the Rise of the UAW (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979).

Nowrocki, Alan, and David Clements, Art in Detroit Public Places (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2008).

Pound, Arthur, Detroit: Dynamic City (New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1940).

Quaife, M.M. This Is Detroit: 250 Years in Pictures (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1951).

Riley, James A., The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2002).

Savage, Rebecca Binno, and Greg Kowalski, Art Deco in Detroit (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2004).

Schramm, Kenneth, Detroit’s Street Railways (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2006).

Sisson, Richard, Christian Zacher, and Andrew Cayton, general editors, The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2007).

Sommers, Lawrence M., ed., Atlas of Michigan (East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 1977).

Thomas, June Manning, Redevelopment and Race: Planning a Finer City in Postwar Detroit (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997).

Woodford, Arthur M., ed., The Michigan Companion (Detroit: OmniData, Inc., 2012).

Articles

Cowan, Russell, “Detroit Giants Lose Park,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 16, 1935, 11. Accessed via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

“9,000 See Ty Cobb Throw a Perfect Strike to Open Hamtramck’s New Base Ball Park,” Detroit News, May 12, 1930.

“Michigan School Segregation Plan Is Failure,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 18, 1935, 7. Accessed via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

“Nashville Giants Transfer Franchise to Detroit,” Philadelphia Tribune, February 21, 1935, 11. Accessed via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Online

DetroitDataGuru.Wordpress.com

ForgottenShow.net

HistoricBostonEdison.org

HistoricDetroit.org

IMDB.com

Michigan.gov

Interviews and Communications

Logan, Sam, publisher of Michigan Chronicle, Telephone interview with author, May 18, 2010.

Shea, Stuart, telephone interviews and e-mail messages to author, 2014.

Unpublished sources

Gillette, Lina, “Detroit Is, Because,” Rudolph Steiner School Ann Arbor, 2013.

Shea, Stuart, 24-7 Baseball MLB Club Broadcasting Database.