A Stepping Stone to the Majors: The Olympic Base Ball Club of Paterson, 1874-76

This article was written by John G. Zinn

This article was published in Spring 2023 Baseball Research Journal

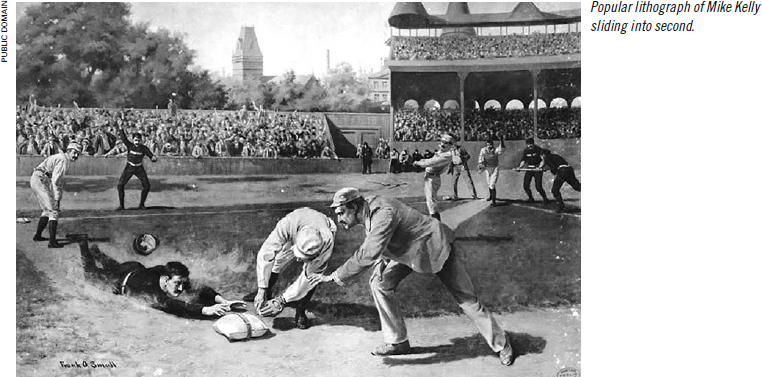

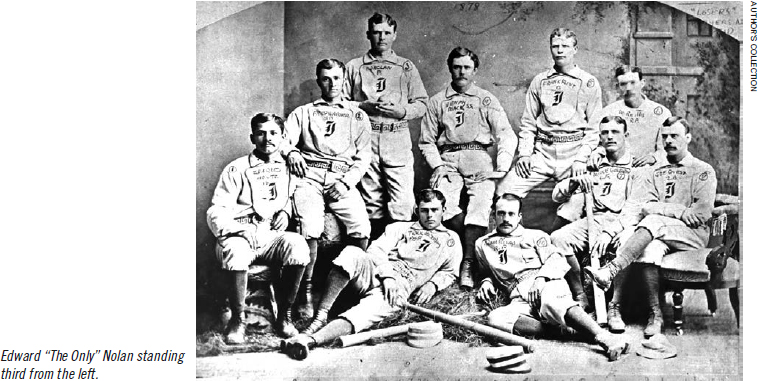

As major league baseball grew throughout the late nineteenth century, a limited number of players earned national recognition for their on-the-field prowess. From that small group emerged an even smaller number who also had charisma and became the equivalent of today’s rock stars. Especially noteworthy was Paterson’s Mike “King” Kelly, considered by some to be baseball’s first matinee idol. Thanks to both his performance and his personality, Kelly earned unprecedented amounts of money, not just from baseball—where at one time he was the game’s highest-paid player—but also from endorsements and off-the-field activities. In addition to playing baseball, Kelly was an actor, the subject of a hit song and, most importantly for our purposes, the “author” of the first baseball autobiography.1 Published in 1888, and almost certainly not written by Kelly, the book describes his baseball career beginning with his first attempts to play organized baseball in Paterson, New Jersey. Unfortunately, the book’s version of Kelly’s early career is incorrect and the inaccuracies have been repeated ever since. Some of this same misinformation has also seeped into the stories of William Purcell, Jim McCormick, and Edward “The Only” Nolan, three contemporary Paterson players who also made it to the major leagues.2 The goal of this essay is to understand what actually happened in Paterson baseball 1874-76 and to explore its significance. The real story matters because historical accuracy always matters, and more importantly, because what did hap pen is both interesting and important.

DEBUNKING THE MYTHS OF KELLY’S EARLY CAREER

In his “autobiography,” Kelly claimed his baseball career began in 1873, at age 15, when his good friend, Jim McCormick, asked if he wanted to join a new baseball team. Initially, the team was to be called the Haymakers, but with McCormick’s support, Kelly convinced the others that Keystones was a better name. Captained by William Purcell, the team featured Nolan as its pitcher until he left for Ohio to join the Columbus Buckeyes in 1876. At that point, according to Kelly, McCormick became the pitcher and Kelly was the catcher, so the two “got a reputation as the Keystone battery” which “stuck to us for many years after.” During the 1876 season, Kelly claimed the Keystones dominated a number of prominent teams, especially the Star Club of Covington, Kentucky, which could not hit McCormick’s pitching. However, “the great games” of the 1876 season were played in a “championship” series against the National League Mutuals, with the two teams alternating wins. After that stellar campaign, Kelly began the 1877 season in Port Jervis, New York, and then, following in Nolan’s footsteps, joined the Columbus Buckeyes.3

One of the few accurate statements in the last para graph is that Kelly joined the Buckeyes during the 1877 season. Leading off the list of inaccuracies is the Key stone Club name, an error that has been repeated religiously ever since. A close reading of the contemporary Paterson newspapers did not find any mention of a Keystone baseball club in that city through 1876. Beginning in 1874 however, there was a Haymaker Club in Paterson. Of the four future major league players, only Kelly was a member.4 No information survives of any part Kelly played in naming the team, but if he did, it is far more likely he wanted the team to be called the Haymakers because that was the name of a prominent club in his birthplace, Troy, New York. While the team’s name has limited significance, far more important is Kelly’s romantic version of a team of teenage novices that more than held its own against some of the leading teams of the day.

As will be seen, the team in question was not the youthful Keystones/Haymakers, but the Olympic Club, a team run by some of Paterson’s leading citizens who had both the ability and financial resources necessary to build a competitive team. Not only was Purcell never the captain of the Olympics, he, Kelly, McCormick, and Nolan never played for the Olympics or any other Paterson team at the same time.5 And while Kelly correctly noted the Olympic Club’s 1876 success against the Star Club from Kentucky, McCormick was not part of it because he was still laboring for one of the city’s junior clubs. Nor did the two ever become a regular battery for the Keystones, Olympics, or other Paterson team.6 Also inaccurate is Kelly’s claim the team alternated wins with the professional Mutuals. In fact, the Olympics lost both 1876 games with the New York team.7 Even if these factual errors are of limited importance, the enduring acceptance of Kelly’s mythical account obscures the real story of how the management of a fairly typical New Jersey baseball team helped four players get started on their way to the major leagues. Before looking at that story however, it would be helpful to have a sense of how baseball developed in New Jersey in general and Paterson in particular.

THE OLYMPIC BASEBALL CLUB OF PATERSON

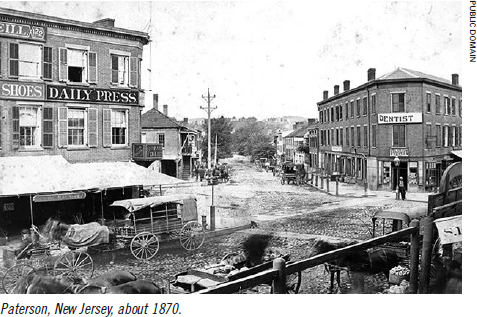

When organized baseball expanded in the mid-1850s, New Jersey was one of the first places the game took hold in a significant way. In 1855 the state had at least 14 baseball clubs, more than either New York or Brooklyn (then an independent city), which were the only other places the New York game was played that year. By the end of the 1860 season, 177 clubs had been founded in 21 New Jersey municipalities, second only to New York in both categories.8 Similar growth might have been expected in Paterson, the state’s third-largest city, but with the exception of an 1855 team sponsored by the Young Men’s Association, there were few organized clubs until 1860.9 The Olympic Club, Paterson’s premier team, was founded in July 1864 and initially played primarily against other local teams.10 By 1866, however, the Olympics were competing at a higher level. Particularly noteworthy were three games against the Irvington Club, the same year that upstart team wreaked havoc with the baseball establishment. Although the Olympics lost two of the three games, including an embarrassing 70-6 defeat, they did manage one victory, something some of the best teams in the country struggled to accomplish.11 Over the next two seasons, the Olympics expanded their horizons even further, touring Connecticut in 1867 and hosting two of the country’s top teams, the Atlantics of Brooklyn and the Union Club of Morrisania the following year.12

In 1869, however, the Olympic Club’s climb up the baseball ladder came to an abrupt halt. The problem, according to the Paterson Daily Press, was that base ball (and cricket) had been “carried to excess” in 1868, “causing heavy loss to our industries by the negligence of employees.”13 Organized baseball activity dropped off so dramatically through 1874 that the Daily Press at one point asked rhetorically, “What has become of our base ball players?”14 Though largely inactive, the Olympic Club played an occasional game, such as an 1873 match against a picked nine.15 In June of 1874, however, it was announced the club would “be resurrected for a brief time,” for a game with the Hewitt Club of Ringwood.16 Playing, “with much of their old time spirit and energy,” the Olympics won a decisive 57-18 victory. More importantly, the same article reported the club was to “be revived, provided, they [the players] receive pecuniary support to compensate for the time they lose in practicing.”17 The publicly stated demand for “pecuniary support” was a clear sign a successful rebirth required good management.

THE OLYMPICS REBORN

It took almost a month, but two July meetings firmly established the second incarnation of the Olympics. Some 50 people attended a July 10 meeting, choosing officers and directors with experience, both on and off the field. Especially important from a management perspective was Dr. John Quin, who was elected president. Quin, a local physician, was a prior Olympic Club president and had practical experience running a baseball club.18 An Irish immigrant with a large medical practice and a reputation for generosity, Quin had been a city alderman and was considered one of Paterson’s “most esteemed citizens.”19 With a reported net worth of $25,000 in 1870, the Paterson physician also did not lack for financial resources. The Daily Press claimed Quin, “one of the most enthusiastic and most liberal supporters of the club,” had convinced several prospective players to join the team who otherwise would have declined.20 Quin and the other club officers were so successful in rebuilding the Olympic Club that a year later, in 1875, they earned well-deserved praise from both the New York Sunday Mercury and the New York Clipper.21 Among those praised was John Westervelt, the club’s vice president, who became president himself in 18 75.22 Westervelt seems to have been an effective officer of the Olympic Club, but when he stepped down as Paterson city treasurer in 1879, some $8,000 was missing. After a few days of back and forth, his family and friends made up the difference and it doesn’t appear Westervelt was ever charged with a crime.23

The Olympic Club was also fortunate to have officers and directors with baseball experience beyond Paterson, especially William St. Lawrence and Milton Sears.24 St. Lawrence played college baseball while a student at nearby Seton Hall and went on to be a prominent lawyer.25 Sears, who ran a family retail business, had even broader baseball experience. After playing for the original Olympics, he moved up to the Union Club of Morrisania and later played for two Ohio teams. Sears’s exposure to baseball beyond Paterson was a plus for new Olympic players hoping to follow in his footsteps.26 Another valuable member was Art Fitzgerald, who was considered a “pioneer” in the sign painting business. Although Fitzgerald’s specific credentials are unclear, early in their careers both Kelly and McCormick reportedly “never signed a contract until they had consulted Mr. Fitzgerald.”27 Both Fitzgerald and Sears also had prior experience as officers or directors of the Olympic Club.28

While each man brought his own unique skills to this endeavor, they shared common traits that were essential to the Olympic Club becoming more than just another local team. Quin, St. Lawrence, Fitzgerald and Sears were successful in their chosen fields. Their basic competence must have been beneficial in operating a successful baseball club. The local prominence of the four men also gave the Olympic Club credibility. There is no better illustration of their standing in Paterson than the fact that each of their deaths, spread over a period of 40 years, was front page news.29 While the accolades were about far more than their part in the Olympic Club, their contributions greatly increased the club’s chances for success both in Paterson and beyond.

Accepting the publicly stated demand for “pecuniary support,” the club’s leaders wasted little time putting funding in place. Just five days after the initial meeting, the Daily Press reported that 40-45 “members” had subscribed over $100. While some of the money went for uniforms and equipment, the club’s organizers decided to openly “compensate those of the nine who are workingmen for the time lost from their shops,” because this was, “the only way to maintain a good nine.”30 By early August, twenty additional members had been recruited, reportedly “mostly wealthy citizens, who will back up the club financially to any extent.”31 These first financial commitments demonstrated, especially to prospective players, that the club’s management was serious. Equally important was management’s recognition the club needed ongoing operating income, which it proposed to generate by charging admission to an enclosed grounds.32

There was nothing new or revolutionary about this approach, but it was far easier to talk about than to do. One of the major reasons for the failure of the Eureka Club of Newark, one of New Jersey’s premier teams of the 1860s, was its inability to successfully execute such a strategy.33 While the Olympic leader ship was unable to create an enclosed facility in 1874, by the following spring the Olympics, along with some other Paterson teams, had formed an association with $2,000 in capital stock and leased land near the Midland Railroad Depot.34 Finished just in time for a June 17, 1875, game with the Atlantic Club of Brooklyn, the grounds included seats for “ladies and gentlemen,” a “neat ticket office,” and “convenient dressing rooms.”35 Enclosed by a fence eight to nine feet high, the grounds could reportedly accommodate crowds of up to 10,000, including space for horses and carriages.36 Admission to Olympic Club games was 25 cents, but was lowered to 10 cents for Paterson junior club matches.37 Paterson newspapers reported attendance for 18 games in 1875, ranging from 150 to 1,750, an average of almost 600 per game or 10,700 in total. Charging 25 cents for admission, the club generated $2,675 in revenue from these games alone. While attendance figures from this era are far from exact, the estimates indicate the Olympics had a regular revenue stream. Since one-third of the gate money went to the nine players, each Olympic player made about $5.45 per game, more than the daily wage of the most skilled workers in one Paterson silk mill that same year.38 Through 1876, management continued to upgrade the grounds and explore other potential revenue sources, including converting the field into a skating rink in the winter time.39

BUILDING A COMPETITIVE TEAM

An enclosed ground was not in itself enough to attract large, paying crowds. Paterson baseball fans, and hope fully visitors from elsewhere, would only put their quarters down if the Olympics consistently put a good team on the field. Fortunately, the renewed baseball fever in Paterson provided a regular source of new players. In just two years, the number of Paterson baseball clubs grew from about six in 1873 to almost 30 in 1875.40 This included a group of seven teams which organized a series of 18 games for a trophy donated by Milton Sears of the Olympics.41 The con tending teams included the Haymakers with Mike Kelly, and the Star Club, probably with Jim McCormick.42 These teams were an informal feeder system for the Olympics, sometimes providing substitutes when the city’s top club was short-handed. Kelly and McCormick got started with the Olympics in just that way, filling in for missing Olympic starters in an October 5, 1875, match.43 One of the missing Olympics that day was Jim Foran, who had himself moved up to the Olympics from another Paterson club.44 Foran, however, was no baseball neophyte. After playing for the Athletic Club of Philadelphia in 1868, he batted .348 for the 1871 Kekiongas of Fort Wayne in the National Association’s initial season.45 Foran had since moved to Paterson, giving the Olympics a player with prior professional experience. While the Olympics added a few players from outside of Paterson, such as Foran and 1876 field captain James Lillis of Hudson County and Rutgers College, the vast majority of their players were from the city.46

Implicit in management’s decision to build an en closed ground and charge admission was recognition that “the most noted clubs in the country” would only visit Paterson if they received financial compensation. The best source of such money was gate receipts.47 For example, the Atlantic Club of Brooklyn, the opponent for the June 1875 opening of the grounds, demanded a guarantee of $75 plus 50 percent of the receipts over $75.48 In 1874, before the club had an enclosed facility, 18 of their 20 games were against New Jersey teams primarily from nearby Newark and Jersey City. Even though the new grounds, or at least the fence, were not available until mid-June of 1875, the Olympics still hosted five games that season against the professional Atlantics, Mutuals, and New Haven clubs. Playing more than twice as many games as in 1874, the club expanded its schedule, increased its revenue and upgraded the level of competition.49 Although the Olympics lost all five games they played against professional teams, they enjoyed considerable success against New Jersey competition.50 In fact, the Olympic Club was awarded the state’s 1875 amateur championship, only to see it withdrawn in part because of claims they were not really an amateur club.51 Early in the following season, the Olympic Club was expelled from the New Jersey State Association of Base Ball Players, but they did not seem to care.52 The Paterson team had loftier goals in mind.

While the Olympics did not play many more games in 1876, the level of competition did improve. In addition to games with the St. Louis and Mutual teams from the National League, the Olympics also hosted two strong regional teams, the Star Club of Covington, Kentucky and the Buckeyes of Columbus, Ohio. Al though they lost all three games to the National League teams, they took two of three from the Kentuckians and won one game from the Buckeyes (with two ties).53 The Olympics also made their first extended road trip in 1876, a six-game visit to New York State that included matches against teams from Syracuse and Rochester. The upgraded and expanded schedule meant increased revenue, while also assisting with player development. Playing against better competition helps players improve and also brings their names to the attention of higher-level clubs. As we shall see, this was especially true of a September 1876 three-game series against the Buckeyes in Paterson.

The players also benefitted from increased media coverage, which was not due solely to an upgraded schedule or better on-the-field performance. Beginning in 1874, club officials began promoting their games in letters to the New York Clipper, a prominent sports weekly.54 As the team improved, management, particularly John Westervelt, continued to inform both the Clipper and the New York Sunday Mercury of the schedule and game results.55 In 1875, the team’s up coming games appeared in the Clipper five times. One year later this ballooned to 17, almost once per week during the season.

The accomplishments of the Olympic Club’s management may be better appreciated in comparison to the experience of another New Jersey team, the Elizabeth Resolutes. Founded in 1864, the Resolutes were New Jersey state champions in 1870 and ’72.56 According to the Elizabeth Daily Journal, 1872 was also a “test year” to determine if the city could build and support a championship caliber club.57 However attendance was so poor at the club’s annual meeting in early 1873 that those present voted to disband the team. Although it seemed the Resolutes had no future, a subsequent meeting of 25-50 of the “best base ball men” in Elizabeth, a gathering not unlike the Olympic Club meeting of July 1874, decided otherwise. First, they adopted a new constitution and elected officers and a board of directors. Then, with little planning of any kind, they made the fateful decision to join the National Association and compete against far more talented and better-financed teams.58 To make matters worse, the Resolutes played their home games outside of Elizabeth and failed to advertise those games.59 The results were both predictable and disastrous: the club went 2-21 and disbanded before the season was over. The management of the Olympic Club not only chose a more realistic level of competition, but found a better location for their games and advertised regularly.

It is very unlikely that Quin, Westervelt, and company intentionally set out to build a launching pad to the major leagues. It is far more likely they loved base ball, wanted Paterson to have a good team and, at the very least, did not want to lose money in the process. Regardless of their intentions, they created just such a platform. First up, perhaps somewhat surprisingly, was not Kelly or McCormick, but Edward Nolan. Nolan was only 18 when the Olympic Club was reborn in July 1874, but he was no stranger to hard work. At age 13 he worked in a silk mill, probably for less than a dollar a day.60 It is not known if Nolan played in the June 16, 1874, game with the Hewitt Club, but fol lowing the July 15 reorganizational meeting he was listed as the club’s left fielder.61 When the Olympic Club took the field for their next game, however, their pitcher was absent. Nolan stepped in and dominated the opposition, allowing only five runs with 11 of the 27 outs “put out behind the bat.”62 When his pitching success continued, the Olympics were smart enough to use Nolan as their starting pitcher for almost every game over the next two years.

In his first season with the Olympics, Nolan pitched in at least 15 of the club’s 20 games, of which the team won 11. It was not always smooth sailing however, either on or off the field. On August 31, the Daily Press reported Nolan had left the Olympics to join the Channels, another Paterson team with aspirations of its own. Nolan’s motivation was likely financial (this was before the Olympics began sharing gate receipts), since the Channels agreed to pay him $10 per game with the understanding that if the money was, “not forthcoming within ten hours,” then, “he throws up his position.” Later in the same article, however, the paper somewhat retracted the story. A few days later, the Press confirmed Nolan had indeed, “returned to the Olympics as pitcher,” and shortly after that demonstrated just “how indispensable he is to the success of the club.”63 Even without Nolan, the Channel Club briefly challenged the Olympics for Paterson’s top spot, recruiting “a professional pitcher” when they could not get the local phenom.64 There was talk of the two teams consolidating, and while there does not seem to have been a formal process, several Channel players, including Jim Foran, joined the Olympics for the 1875 season.65

While Nolan certainly pitched effectively in 1874, especially for an 18-year-old, playing for the Olympics also allowed him to learn and grow as a pitcher. The best example came in the short-lived Channel rivalry. In the first game of a best-of-three series, the Channels had “studied [Nolan’s] pitching so closely, they had no difficulty,” pounding him for 19 runs.66 When the two teams met again on October 2, the Olympics were unwilling to risk a repeat poor performance by Nolan. They started another pitcher instead, but trailed, 10-1, after four innings. Given a second chance, Nolan showed he had learned from the first game. He threw five shutout innings as the Olympics rallied for a 12-10 win.67 In the deciding game two weeks later, Nolan was again dominant. Not only was his pitching “more than usually effective,” he caught “hot liners” in a way “that would have reflected honor on a Japanese juggler.”68 By season’s end Nolan had become so popular, young boys in Paterson were putting pedestrians at risk by throwing rocks in imitation of Nolan’s “style” of “swift balls,” thrown, “with that sudden and peculiar underhand jerk.”69

Playing for the Olympic Club offered multiple benefits to Nolan, not the least of which was pay well above what he could earn in a Paterson silk mill. Blessed with natural talent and fortunate to be in the right place at the right time, Nolan got the opportunity to display and develop that talent on Paterson’s best baseball team. The young pitcher also attracted attention from far outside Paterson. A St. Louis club supposedly offered him $1,000 for the 1875 season, which he reportedly declined.70 The Olympics could not and would not pay that kind of money, but they did offer Nolan further opportunities to develop before leaving Paterson. In 1875 Nolan pitched in more than twice as many games and against better competition, including three professional clubs. All told, Nolan and his defenders allowed 6.3 total runs per game, down from 9.2 the prior year, despite pitching against better teams. In 14 of those games, he allowed four or fewer runs, holding six opponents to no more than two. By this point the young pitcher had become a fan favorite, especially with his “admiring lady friends,” who gave him “a most resplendent [baseball] suit of blue silk.”71 Still modest, Nolan “kept his coat” on before the game, but when he removed it, he and his female fans were rewarded with “a murmur of surprise and delight” at “his splendid blue silk shirt.”72

Despite his success, Nolan was hit hard by both the Alpha Club of Newark and the Elizabeth Resolutes, the latter club just two years removed from the National Association.73 Nor did Nolan do much better on an August road trip to Trenton, where he suffered a 17-3 loss, his worst outing of the year. Leading 3-0 after six innings, the combination of heat and shaky defense caused Nolan to lose “his head” making his pitching “but child’s play” to hit.74 Despite those rough spots, Nolan had a stellar season. It was no surprise when he signed to play for the Columbus Buckeyes in early 1876.75 After one season in Ohio, Nolan moved to Indianapolis, one level below the National League. There, as Richard Hershberger has documented, he had a memorable season, earning one of baseball’s greatest nicknames: “The Only.”76 A year later, Indianapolis, and Nolan with them, was in the National League. Even if Indianapolis had not reached the NL in 1878, there is little doubt that Nolan would have been on another League club, just four years after his Olympic debut.

Logic and Mike Kelly’s version of events suggest that after Nolan left Paterson, Jim McCormick stepped in as the Olympics lead pitcher. Logic, however, does not al ways apply in baseball. According to Kelly, he and McCormick played on the same Paterson team from the beginning of their baseball careers, but there is no documentation to support that claim. Described as, “a new aspirant for baseball honors,” McCormick first appeared in Paterson newspaper accounts as a substitute for the Olympics in an October 4, 1875, victory over the Reliance Club of New York.77 Even with Nolan gone, however, McCormick was not a member of the Olympics in early 1876, pitching instead for the Star Club of Paterson. Other than one other substitute appearance for the Olympics, he stayed with the Star Club through mid-August.78 McCormick did, however, catch the attention of the local press when he pitched for the Star Club in a 12-7 loss to the Olympics. The Daily Press noted that his pitching was “something like Nolan’s,” and predicted that “practice would give him a very good delivery.”79 Less than a week later, the Newark Courier praised Mc Cormick’s “puzzling ball” after a dominant performance against the Star Club of Newark.80

About that same time, Hugh O’Neil, formerly of the Atlantic Club of Brooklyn and the Olympics’ fourth replacement for Nolan, suffered an injury and was unable to pitch.81 That same day, the Paterson Daily Guardian praised McCormick, noting “we would not be surprised if he should at some day prove a second Nolan.”82 Recognizing the solution to their pitching problem was right there in Paterson, the Olympics chose McCormick to pitch in an August 18 game against the Alaska Club of New York, and he never looked back. Pitching with “rare judgement,” McCormick allowed only five runs, three in one inning when he briefly “lost his head.”83 The new Olympic pitcher did even better in the next two games, allowing only a total of six runs against the Alaska Club.84 McCormick pitched in 17 games for the Olympics in 1876, allowing 4.4 runs per game, better even than Nolan in 1875, against arguably better competition.

The new Olympic starter was also fortunate to be given a chance to pitch on a big stage, an opportunity he did not waste. In late September, the Buckeyes, with Nolan, arrived in Paterson for a three-game series. McCormick allowed four runs in the first game, which ended in a tie. In the second game, he shut out the Buckeyes for eight innings, but they rallied to even the score at 4-4 in the ninth. Although Columbus had a runner on third with none out, McCormick showed his mettle and retired the side for a second straight tie. It was small consolation to the Paterson pitcher who, according to the Daily Guardian, “weeps and re fuses to be comforted.”85 Perhaps the frustration gave McCormick even more motivation in the series finale. He allowed only one run in a 3-1 Olympic victory.86 Although his stay with the Olympics was relatively brief, McCormick took full advantage of an ideal plat form to display his skills. Based on his performance in the three games against Columbus, it was no surprise the club signed him for the 1877 season.87 Later that same year, McCormick joined Nolan in Indianapolis and moved with the team to the National League in 1878. The significance of the two pitchers’ accomplishments was not lost in Paterson, where the Daily Guardian proclaimed, “Paterson has furnished two of the best amateur pitchers in the country.”88

“BLONDIE”

It is probably fitting that William Purcell’s Paterson baseball career is the least documented of the four players. Although he had a 12-year major league career, Purcell has the dubious distinction of being one of the relatively few major league players whose death date and burial site are unknown. While Kelly claimed Purcell was the team captain, he was never captain of the Olympics. He played only eight games for the club. Also, unlike the others, Purcell’s name has not been found in box scores for Kelly’s Haymakers, McCormick’s Star Club, or any other Paterson team. With no advance notice, the future major leaguer played right field for the Olympics in a May 23, 1876, game against a Brooklyn team, batting third and getting two hits.89 Purcell appeared in seven more Olympics games, highlighted by a June 14 home run off McCormick in a victory over the Star Club.90 The only other newspaper attention Purcell attracted was criticism for some “decidedly bad” play in the field.91

Somewhat surprisingly, when Purcell’s name dis appeared from the Olympic lineup after a July 4, 1876, game, he did not resurface with another Paterson club. Instead, in early August, Purcell was pitching for the Delaware Club of Port Jervis, New York.92 Although Purcell returned to Paterson for the winter and briefly played there in early 1877, he went back to Port Jervis and played for the New York team through the middle of June.93 After pitching effectively against the Cricket Club of Binghamton, he was signed by that team, initially for $30 a month, which was raised to $70 before the season ended.94 When the Cricket Club disbanded after the 1877 season, the players, including Purcell, were “engaged” to play in Utica the following season.95 His performance must have been satisfactory since he was then signed by Syracuse when that club joined the National League in 1879. It marked the beginning of a major league career that lasted through 1890.96 Purcell’s tenure with the Olympics was brief, but the visibility of playing for Paterson’s top team clearly helped when the Port Jervis team decided to upgrade its roster. Like Nolan and McCormick, Purcell took full advantage of the opportunity.97

“KING” KELLY

Mike Kelly’s Paterson years are discussed last because, even though he had without question the greatest major league career, he was the last to leave the city. The future Hall of Famer did attract the attention of the press relatively early. The Daily Press praised his play at shortstop in a November 1874 Haymaker victory over the Star Club.98 Kelly must have also caught the attention of the Olympic Club, since at least twice in 1875 he filled in when they were shorthanded. In the second contest in early October, both Paterson papers praised his play at catcher, for doing “remarkably well” in “facing Nolan’s pacers” for the first time.99 In spite of this performance and Kelly’s claim that he and McCormick became the team’s battery, once Kelly made the Olympic starting lineup in 1876, he played almost exclusively in the outfield.

Kelly’s performance in his one season with the Olympic Club was marked by both praise and criticism in the newspapers, suggesting that while he played well, it was also a learning experience. His fielding was called “perfect” in one early season game and when he did get a rare chance to catch in September, he, “played the position like a veteran, his throwing de serving special notice.”100 He went 3 for 8 in two games against the Star Club of Kentucky, got a hit off Nolan in one of the Buckeye games, and gave “a fine display of batting” in executing a fair-foul hit in the final game of the series.101 The hit off Nolan apparently redeemed Kelly, since Nolan was reportedly deter mined to hold him hitless. After meeting the challenge, Kelly supposedly “stands several feet higher today than usual.”102 Full box scores survive for 24 of Kelly’s 47 games with the 1876 Olympics, in which he batted .279, which hardly seems Hall-of-Fame-worthy at first glance. A closer look, however, reveals a picture of a developing young player. After batting a woeful .218 in the first 13 games, Kelly had a blistering .347 batting average in the last 11 contests.

Further signs of youth and immaturity were negative comments about what sound like attitude issues. In an early season game, the Daily Press commented that after hitting safely Kelly was put out at first, “through neglect in not paying attention to the game.”103 Such concerns continued when, supposedly, a game needlessly went into extra innings due to Kelly’s “recklessness” on the bases. Anticipating problems major league managers and umpires would later have with Kelly, the Daily Guardian complained, “Captain Lillis had no control over him and he evidently intends to do as he pleases.”104 No wonder the paper later dubbed him, “the irrepressible Kelly.”105 Whether due to concerns about his attitude or simply the informal nature of scouting and player evaluation, Kelly was the only one of the four still in Paterson when the 1877 season began. The Olympic club had a hard time get ting organized for the new season, and Kelly began the year playing for the Rutan Club, a relatively new junior team.106 Named after local funeral director Charles Rutan, according to the Daily Guardian, the club’s “intention is to bury everything they tackle.”107

The Olympic Club finally got on the field, and fortunately for Kelly, played three games against the Delaware Club of Port Jervis and Olympic alumnus Bill Purcell.108 Kelly was signed by the Port Jervis team in late June of 1877, briefly giving the team an all-Paterson battery.109 Kelly won high and consistent praise for his catching at Port Jervis, marred only by one apparent refusal to chase a passed ball.110 The Paterson prospect had clearly matured, since the local paper mourned his absence in late August, claiming the club’s lack of leadership “contrasted sadly with the Delawares under M. Kelly as captain.”111 The loss was permanent as Kelly headed west to join the Columbus Buckeyes, playing right field and serving as “change [substitute] catcher.”112 Kelly batted just .156 in 23 games in Columbus.113 That would prove no long-term obstacle, as 1878 found Kelly with Cincinnati on his way to the major leagues and the Hall of Fame.

COMPARABLE TEAMS

Four players from one club reaching the majors is a notable accomplishment. It raises the question of whether the Olympic experience was unique. While no exhaustive study was made by the author, initial research and suggestions from other historians produced four teams from 1869 to 1876 that sent at least four players to the major leagues or the National Association. Of these, the Easton Club from Pennsylvania and the Neshannocks of New Castle, Pennsylvania, differ from the Olympics in that they were not home grown clubs. The Easton lineup was largely recruited by Jack Smith from, “the ballfields of Philadelphia,” and became “arguably the best amateur club in the country,” in 1874. Unsurprisingly, the Easton Club was a prime target for professional teams. National Association clubs signed eight of their players.114 Similarly Charlie Bennett, Ned Williamson, George Creamer, and Sam Weaver all played for the Neshannocks and in the majors, but only the ill-fated Bennett was from New Castle.115

Although highly successful, the Star Club of Boston doesn’t seem to have attracted a great deal of contemporary media attention, probably because they were vastly overshadowed by the Red Stocking teams that dominated the National Association. However, five members of the Star Club-Curry Foley, Chub Sullivan, John Morrill, Dennis Sullivan, and Lew Brown—either were born or grew up in Boston and eventually reached the major leagues. The Star club was so talented they won the junior championship of Massachusetts in 1874 without losing a single match.116 Finally, there is the Alert Club of Rochester, which Priscilla Astifan has written about in her comprehensive history of base ball in that city.117 Five players from that team—John Glenn, Sam Jackson, Eugene Kimball, John McKelvey, and Ezra Sutton—played in the National Association and/or the National League. Like the Olympics, the Alert Club gave their players the opportunity to play against good competition, especially during extensive 1869 road trips.118

In 1875, the same year the Olympic club did or did not win the New Jersey state championship, the New York Clipper estimated there were at least 2,000 base ball clubs in the United States.119 If that estimate is anywhere near accurate, it demonstrates how unusual it was for one club to send four players to the major leagues. While it may be more romantic or heroic to believe what happened in Paterson was a rags-to-riches tale, led by future Hall of Famer Mike Kelly, the truth, as we have seen, is somewhat different. Kelly, McCormick, Purcell, and Nolan had plenty of talent, but their success also depended on a support system provided by another group of men still largely unknown to history. Building a launching pad to the majors was not their intent. They wanted a successful team, understood what went wrong with the original Olympics, and re solved to do better. Unintentionally, these Paterson men anticipated the kinds of things up and coming players, then and now, need to reach the game’s high est levels. It may not be the stuff of myth and legend, but it is no less interesting or important.

JOHN ZINN is a baseball historian with special interest in the Brooklyn Dodgers and New Jersey baseball history. He is the author of three books about the Brooklyn Dodgers and is a two time winner of the Ron Gabriel award for research on the Dodgers. John was also the recipient of the 2020 Russell Gabay Award by SABR’s Elysian Fields Chapter. A longtime SABR member, he also writes a baseball history blog entitled A Manly Pastime. John is the scorekeeper for the Flemington Neshanock vintage baseball team. He holds BA and MBA degrees from Rutgers University and is a Vietnam veteran.

Notes

1. Peter M. Gordon, “King Kelly,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/king-kelly.

2. For the most literal acceptance of Kelly’s version of his baseball years in Paterson see Mary Appel’s Slide Kelly Slide: The Wild Life and Times of Mike “King” Kelly Baseball’s First Superstar (Latham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1996), 16-18.

3. Mike Kelly, Play Ball: Stories of the Diamond Field (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2006, first published 1888), 11-13.

4. Paterson Daily Press, September 11, 1874, 3, November 10, 1874, 3.

5. Paterson Daily Press, August 22 1874, 3, Paterson Daily Guardian, July 13, 1875, August 12, 1876. From 1874 to 1876, the Paterson newspapers list Milton Sears, a man named Wiggins and James Lillis as Olympic captains.

6. New York Clipper, July 15, 1876, 123, In the 15 box scores that survive when McCormick pitched for the Olympics, Kelly caught just three games.

7. Paterson Daily Press, October 7, 1876, 3, Paterson Daily Guardian, October 12, 1876.

8. John G. Zinn, A Cradle of the National Pastime: New Jersey Baseball, 1855-1880 (Princeton, New Jersey: Morven Museum and Garden, 2019), 28-29.

9. Newark Daily Advertiser, August 22, 1855, 2, New York Sunday Mercury, May 6, 1860, https://protoball.org/Paterson, NJ.

10. Paterson Daily Register, July 15, 1864.

11. Paterson Daily Press, July 14, 1866, 3, September 6, 1866, 3, October 6, 1866, 3.

12. Paterson Daily Press, September 23, 1867, 2, June 2, 1868, 2, July 28, 1868, 2.

13. Paterson Daily Press, July 6, 1869, 2, July 22, 1869, 3.

14. Paterson Daily Press, March 29, 1871, 3, August 28, 1872, 3.

15. Paterson Daily Press, June 3, 1873, 3.

16. Paterson Daily Press, June 11, 1874, 3.

17. Paterson Daily Press, June 17, 1874, 3.

18. Paterson Daily Press, September 4, 1867, 3, July 11, 1874, 3.

19. The Paterson Morning Call, July 14, 1887, 1, Paterson Daily Register, April 11, 1862, 2, Paterson Daily Press, January 4, 1870, 2.

20. 1870 United States Census, Paterson Daily Press, July 16, 1874, 3.

21. New York Sunday Mercury, June 27, 1875, New York Clipper, July 10, 1875, 117.

22. Paterson Daily Press, April 28, 1875, 3.

23. Paterson Daily Press, June 5, 1879, 3, June 6, 1879, 3, June 7, 1879, June 9, 1879, June 10, 1879, 3, June 11, 1879, 3.

24. Paterson Daily Press, July 11, 1874, 3.

25. Paterson Evening News, July 9, 1928, 1, New York Clipper, May 21, 1870, 50.

26. Sporting Life, April 24, 1909, 1, Paterson Daily Press, July 11, 1868, 3, Morning Call, April 3, 1909, 1.

27. Morning Call, April 22, 1918, 1.

28. Paterson Daily Press, October 30, 1866, 3.

29. Morning Call, July 14, 1887, 1, April 3, 1909, 1, April 22, 1918, 1, Paterson Evening News, July 10, 1928, 1.

30. Paterson Daily Press, July 16, 1874, 3.

31. Paterson Daily Press, August 5, 1874, 3.

32. Paterson Daily Press, July 16, 1874, 3.

33. Zinn, 68, 81, 84.

34. Paterson Daily Press, May 26, 1875, 3.

35. Paterson Daily Guardian, June 13, 1875.

36. Paterson Daily Press, June 18, 1875, 3.

37. Paterson Daily Press, June 16, 1875, 3, August 20, 1875, 3.

38. New York Clipper, November 27, 1875, 275, Joseph Weeks, Report on the Statistics of Wages in Manufacturing industries (Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office, 1886), 371, The John Dunlop Mill in Paterson reported 1875 daily wages ranging from 25 cents for a cleaner to $5 for a foreman.

39. Paterson Daily Press, November 17, 1875, 3, May 6, 1876, 3, August 10, 1876, 3.

40. Paterson Daily Press, June 5, 1873, 3, July 16, 1873, 3, July 24, 1873, 3, July 29, 1873, 3, August 11, 1873, 3, Paterson Daily Guardian, May 22, 1875, September 28, 1875. On May 22, 1875, the Daily Guard/an claimed there “about twenty” teams not worthy of media attention in addition to the seven named in September 28, 1875 article.

41. Paterson Daily Press, September 13, 1875, 3, Paterson Daily Guardian, September 28, 1875.

42. Paterson Daily Guardian, September 28, 1875.

43. Paterson Daily Press, October 5, 1875, 3.

44. Paterson Daily 44 Press, October 29, 1874, 3.

45. Peter Morris, William J. Ryczek, Jan Finkel, Leonard Levin and Richard Malatzky, Baseball Founders: The Clubs, Players and Cities of the Northeast That Established the Game (Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Co., 2013), 238, www.retrosheet.org.

46. Paterson Daily Guardian, June 23, 1876, August 12, 1876, Paterson Daily Press, June 23, 1876, 3.

47. Paterson Daily Press, July 16, 1874, 3.

48. Paterson Daily Press, June 16, 1875, 3, June 18, 1875, 3.

49. New York Clipper, November 20, 1875, 266.

50. New York Clipper, November 20, 1875, 266.

51. Paterson Daily Press, November 13, 1875, 3, New York Clipper, November 27, 1875, 275, December 11, 1875, 293, the Olympics claimed the players only compensation was a share of the gate receipts.

52. New York Clipper April 22, 1876, 29.

53. Paterson Daily Press, May 27, 1876, 3, July 7, 1876, 3, July 8, 1876, 3, July 10, 1876, 3, October 7, 1876, 3, New York Clipper, September 20, 1876, 211, October 21, 1876, 235.

54. New York Clipper, August 15, 1874, 157.

55. New York Clipper, September 18, 1875, 197, New York Sunday Mercury, June 27, 1875.

56. Zinn, 93-97.

57. Elizabeth Daily Journal, August 8, 1872, 3.

58. Elizabeth Daily Journal, January 9, 1873, 3, January 14, 1873, 3.

59. New York Sunday Mercury, May 4, 1873, May 11, 1873.

60. 1870 United States Census, Weeks, 371.

61. Paterson Daily Press, July 16, 1874, 3.

62. Paterson Daily Press, July 17, 1874, 3.

63. Paterson Daily Press, August 31, 1874, 3, September 3, 1874, 3, September 4, 1874, 3.

64. Paterson Daily Press, September 12, 1874, 3.

65. Paterson Daily Press, October 6, 1874, 3, October 7, 1874, 3, October 29, 1874, 3, in addition to Foran, James Mullen, John Mullen, James Lillis, Wiggins and Tredo played at least 10 games for the Olympics in 1875.

66. Paterson Daily Press, September 12, 1874, 3.

67. Paterson Daily Press, October 3, 1874, 3.

68. Paterson Daily Press, October 17, 1874, 3.

69. Paterson Daily Press, October 27, 1874, 3.

70. Paterson Daily Press, May 25, 1875, 3.

71. Paterson Daily Guardian, September 4, 1875.

72. Paterson Daily Guardian, September 4, 1875.

73. Paterson Daily Press, June 29, 1875, 3, August 10, 1875, 3.

74. Paterson Daily Press, August 20, 1875, 3, Paterson Daily Guardian, August 18, 1875, Trenton State Gazette as quoted in the Daily Guardian of August 19, 1875.

75. New York Clipper, February 5, 1876, 355.

76. Richard Hershberger, “How Good Was Ed ‘The Only’ Nolan, Base Ball 11-New Research on the Early Game, 2019, 214-15, according to Hershberger’s calculations Nolan’s 1877 record was 57-29-9.

77. Paterson Daily Press, October 5, 1875, 3, Paterson Daily Guardian, October 5, 1875.

78. Paterson Daily Press, June 17, 1876, Paterson Daily Guardian, August 19, 1876.

79. Paterson Daily Press, June 15, 1876, 3.

80. Newark Courier quoted in the Paterson Daily Guardian, June 23, 1876.

81. Paterson Daily Guardian, June 23, 1876, Paterson Daily Press, June 23, 1876, 3 August 16, 1876, 3.

82. Paterson Daily Guardian, August 16, 1876.

83. Paterson Daily Guardian, August 19, 1876.

84. Paterson Daily Guardian, August 24, 1876, August 26, 1876.

85. Paterson Daily Guardian, September 21, 1876.

86. New York Clipper, September 30, 1876, 211, Paterson Daily Guardian, September 23, 1876.

87. New York Sunday Mercury, January 21, 1877.

88. Paterson Daily Guardian, September 19, 1876.

89. Paterson Daily Press, May 24, 1876, 3.

90. Paterson Daily Press, June 15, 1876, 3.

91. Paterson Daily Guardian, June 17, 1876, June 21, 1876.

92. Evening Gazette (Port Jervis), August 3, 1876, 1.

93. Paterson Daily Guardian, May 11, 1877, 3, Paterson Daily Press, June 15 1877, 3.

94. Paterson Daily Press, June 15, 1877, 3, July 10, 1877, 3.

95. New York Sunday Mercury, October 21, 1877.

96. New York Clipper, January 11, 1879, 331.

97. Paterson Daily Guardian, August 7, 1876.

98. Paterson Daily Press, November 10, 1874, 3.

99. Paterson Daily Press, July 31, 1875, 3, October 5, 1875, 3, Paterson Daily Guardian, October 5, 1875.

100. Paterson Daily Guardian, May 20, 1876, September 16, 1876.

101. Paterson Daily Guardian, July 7, 1876, July 10, 1876, September 21, 1876, September 23, 1876.

102. Paterson Daily Guardian, September 19, 1876, September 21, 1876.

103. Paterson Daily Press, May 31, 1876, 3.

104. Paterson Daily Guardian, August 12, 1876.

105. Paterson Daily Guardian, September 23, 1876.

106. Paterson Daily Guardian, May 11, 1877, 3, May 19, 1877, 3, May 24, 1877, 3.

107. Paterson Daily Guardian, August 30, 1876.

108. Paterson Daily Guardian, May 30, 1877, 3, New York Clipper, June 9, 1877, 83.

109. New York Sunday Mercury, July 1, 1877.

110. Evening Gazette, July 10, 1877, 1, July 14, 1877, 1.

111. Evening Gazette, August 21, 1877, 1.

112. Evening Gazette, August 7, 1877, 1.

113. New York Sunday Mercury, October 14, 1877.

114. Morris, Ryczek, et al, 258-59, email from Richard Hershberger, January 27, 2020, William J. Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings: A History of Baseball’s National Association, 1871-1875 (Wallingford, Connecticut: Colebrook Press, 1992), 179, the eight were George Bradley, Tom Miller, Joe Battin, Denny Mack, Jim Devlin, Chick Fulmer, Bill Parks and John Abadie.

115. New York Clipper, March 11, 1876, 394, November 4, 1876, 251.

116. New York Clipper, December 19, 1874, 301, Boston Globe, May 2, 1887, 8.

117. Priscilla Astifan, Rochester History, Volume LXIII, Winter 2001, No 1, 3-6.

118. Priscilla Astifan, Rochester History, Volume LXIII, Winter 118 2001, No 1, 5-6.

119. “The Amateur Season of 1875,” New York Clipper, November 20, 1875, 269.