A View from the Bench: Baseball Litigation and the Steel City

This article was written by John Racanelli

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

“Hardly anything in America symbolizes a large city more than its National or American League baseball team. To take the Pittsburgh baseball team out of Pittsburgh would be to deprive its people of the opportunity for a spontaneous outburst of civic pride, for which there is no substitute. In fact, it is practically impossible to visualize Pittsburgh without its Pirates. To take the Pirates out of Pittsburgh would be like taking them out of the history of the Spanish Main, it would be like diverting the course of the Allegheny and Monongahela River so that they would not form the Ohio at the immortally historical Fort Pitt, it would be like turning the Golden Triangle into a Tin Pin Alley, it would be like transforming the 42-story Cathedral of Learning into a one-room country schoolhouse.”1

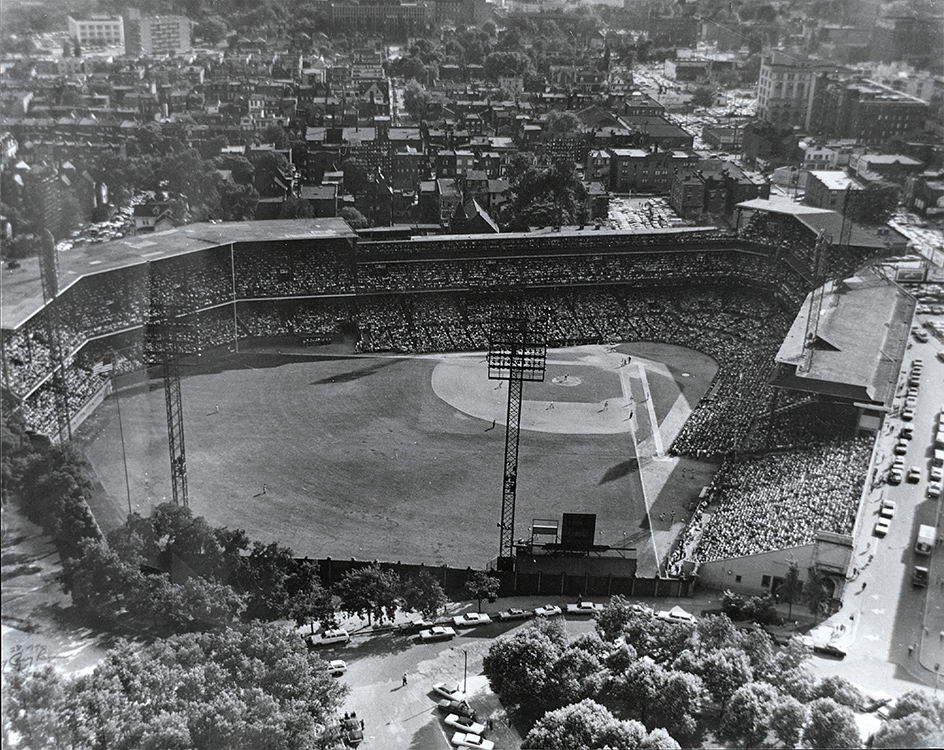

So rhapsodized Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice Michael Musmanno in 1966 when the court was tasked with deciding whether the city of Pittsburgh overstepped its authority in securing $28 million to finance the construction of Three Rivers Stadium. Long before this decision paved the way for the construction of the ballpark that would replace venerable Forbes Field, however, the courts played a vital role in shaping Pittsburgh’s baseball history.

Here are some stories of Pittsburgh baseball in the courts.

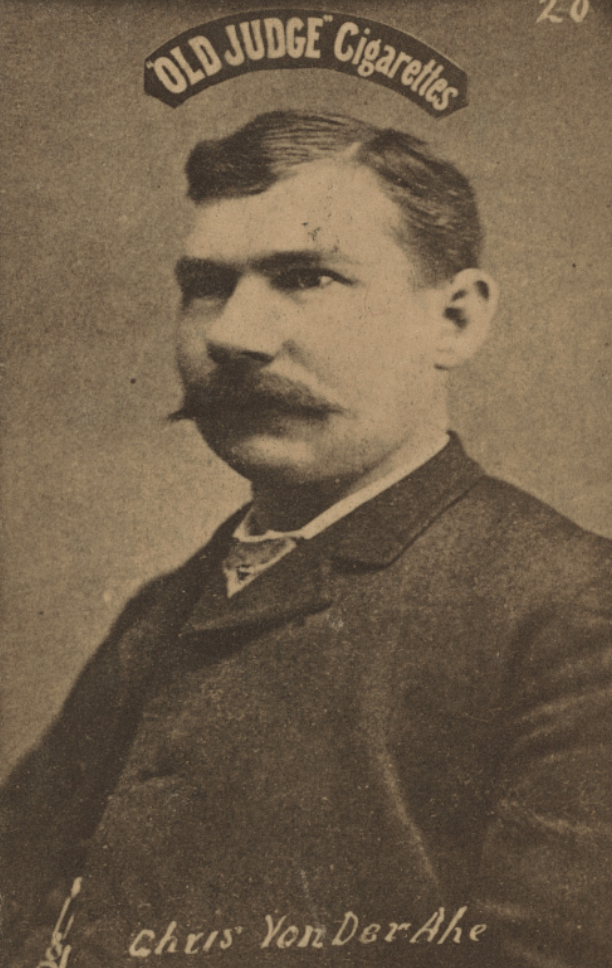

MARK BALDWIN, CHRIS VON DER AHE, AND THE BIRTH OF THE PIRATES

In 1890, Pittsburgh native Mark Baldwin pitched for the Chicago Pirates in the Players’ League’s only year of existence. When the league folded at the end of the season, the rights of all players reverted to the National League or American Association teams they had played for in 1889.2 Accordingly, Baldwin was to report back to the AA Columbus Solons for the 1891 season; however, he and several other players, including pitcher Silver King and infielder Charlie Reilly, refused to report to their former clubs, signing instead with Pittsburgh.3 The Philadelphia AA team owners felt Pittsburgh had acted “piratical” in their signing of the players, and thus the nickname “Pirates” was born. The team didn’t formally adopt the name until 1931, but the nickname appeared on their uniforms as early as 1912.4

In 1890, Pittsburgh native Mark Baldwin pitched for the Chicago Pirates in the Players’ League’s only year of existence. When the league folded at the end of the season, the rights of all players reverted to the National League or American Association teams they had played for in 1889.2 Accordingly, Baldwin was to report back to the AA Columbus Solons for the 1891 season; however, he and several other players, including pitcher Silver King and infielder Charlie Reilly, refused to report to their former clubs, signing instead with Pittsburgh.3 The Philadelphia AA team owners felt Pittsburgh had acted “piratical” in their signing of the players, and thus the nickname “Pirates” was born. The team didn’t formally adopt the name until 1931, but the nickname appeared on their uniforms as early as 1912.4

King’s refusal to return to the St. Louis club incensed hot-blooded Browns owner Chris Von der Ahe, who was convinced that Baldwin had made a trip to Missouri specifically to persuade King to sign with Pittsburgh.5 Seeking his pound of flesh, Von der Ahe swore out a complaint against Baldwin on charges of felony conspiracy and had him arrested on March 5, 1891.6

Naturally, Baldwin denied the charges and King averred via affidavit that Baldwin had not swayed him to sign with Pittsburgh. Baldwin prevailed and was cleared of all charges at his trial in St. Louis on April 3. The victory was short-lived, however, as Von der Ahe had Baldwin rearrested as he left the courthouse, claiming that the conspiracy was perfected when King failed to report to the Browns on April 1.7

Soon after Baldwin was acquitted of the second set of conspiracy charges, he sued Von der Ahe in Philadelphia for malicious prosecution.8 Due to continuous deliberate delays on the part of Von der Ahe, however, Baldwin eventually dismissed the Philadelphia case and brought the same allegations against Von der Ahe in Pittsburgh in May 1894, seeking $10,000 in damages.9

Cleverly timed by Baldwin, this warrant was served on Von der Ahe right as he arrived at Pittsburgh’s Exposition Park on May 3 for the first of a three-game set between the Browns and Pirates. After being advised by the police officer that he was to post bail or stay in jail until the hearing, Von der Ahe sought refuge in the office of Pirates team president William Kerr, where Kerr posted the $1,000 bond for Von der Ahe.10

When the malicious prosecution case was tried in May 1895, Baldwin triumphed and was awarded $2,500; however, a new trial was granted due to alleged jury tampering.11 The case was retried in January 1897 and Baldwin prevailed again with a similar award of $2,525 (approximately $75,000 today).12 Von der Ahe promptly skipped town without paying Baldwin the verdict amount or repaying the $1,000 bond.

True to form, Von der Ahe appealed the case to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. But the court agreed with the jury and affirmed the verdict in favor of Baldwin on January 3, 1898.13 On the heels of the ruling, Baldwin sued the bondsman (now former Pittsburgh club president William Nimick) to recover the verdict amount.14 Nimick, in turn, wrote several times to Von der Ahe demanding repayment of the bond but received no response.15 Undeterred, Nimick hatched a devious plan to return Von der Ahe to Pittsburgh.

Nimick hired a private detective, Nicholas Bendel, who was to trick Von der Ahe into meeting for dinner at a St. Louis hotel on February 7, 1898. When Von der Ahe arrived, Bendel handcuffed him and forced him into a carriage, whose driver was instructed to drive around aimlessly until Von der Ahe could board the train to Pittsburgh.16 When Von der Ahe arrived in Pittsburgh, he was taken directly to the federal courthouse, where Judge Marcus Acheson released him on $2,500 bail.17

At the hearing held on February 8, Von der Ahe argued that his arrest and forcible return to Pittsburgh was tantamount to imprisonment for debt, which had been abolished in 1842.18 Judge Joseph Buffington, however, held that Nimick had the right to pursue Von der Ahe “into another state; may arrest him on the Sabbath; and, if necessary, may break and enter his house” to apprehend him, subject to the properly entered bail piece.19

Accordingly, Von der Ahe’s arrest in St. Louis and return to Pittsburgh was found perfectly legal in light of his failure to repay the bond.20 Von der Ahe finally settled with Baldwin in September 1898, bringing closure to this strange and protracted legal battle.21

OH, THE IRONY! THE PIRATES ARE PIRATED!

Up until 1938, Pirates games at Forbes Field were not broadcast to local fans at the behest of club president William Benswanger, “long considered one of the arch-enemies of broadcasting home games,” as the Pittsburgh Press called him.22 General Mills and the Socony-Vacuum Oil Company had purchased, for the princely sum of $17,500, exclusive rights to broadcast Pirates road games and held an option to broadcast home games if Benswanger ever lifted the ban.23

Up until 1938, Pirates games at Forbes Field were not broadcast to local fans at the behest of club president William Benswanger, “long considered one of the arch-enemies of broadcasting home games,” as the Pittsburgh Press called him.22 General Mills and the Socony-Vacuum Oil Company had purchased, for the princely sum of $17,500, exclusive rights to broadcast Pirates road games and held an option to broadcast home games if Benswanger ever lifted the ban.23

But Pittsburgh radio station KQV’s enterprising young broadcaster, Paul Miller, devised an ingenious method to transmit Pirates home games with just “a few minutes delay” during the 1938 season.24 KQV leased third-floor space in a house on Boquet Street adjacent to Forbes Field and, using field glasses, Miller was able to quickly re-create the game for his radio listeners.25

Not surprisingly, KQV’s actions riled team ownership, who, along with General Mills and Socony-Vacuum, sued KQV asking the court to stop the unauthorized broadcasts and for damages of $100,000.26 Not coincidentally, KQV’s request to carry the broadcast of the 1938 All-Star Game from Cincinnati was denied as a reprisal for its pirated Pirates broadcasts.27

Initially, the Pirates could not determine how KQV was getting the game information so quickly. Staffers carefully watched for fans dropping written accounts from the stands, signaling to nearby rooftops, or talking over vest-pocket radios.28 The staff “detectives” finally located KQV’s base of operations by erecting a large sheet of canvas in such a way as to individually block each of the houses on Boquet Street while they listened to the ongoing broadcast. When the sheet was placed in front of Miller’s vantage point—“gadzooks!”—KQV went silent.

Undaunted, KQV fought back, contending that the ballgames were “news” and vowing to continue broadcasting the “doings of Paul Waner, Johnny Rizzo and all the lads.”29 KQV’s attorney, former Judge Elder Marshall, argued that the core of the matter was “whether a person shall be restrained from seeing things on his own property and not be permitted to tell about the things he witnesses.”30 KQV’s position was based in part on a 1936 case in which telegraph accounts of New York Giants games were being distributed without the team’s consent.31 The New York court ruled against the Giants, deciding that the game ticket gave each fan a complete license to give an account of the game when and in whatever form he or she chose.32 Marshall maintained that KQV’s position was even stronger in that they were observing the ballgames from a vantage point in which they held a leasehold interest.33

In the KQV case, however, Judge Frederic Schoonmaker disagreed with the reasoning in the Giants case and granted a preliminary injunction, holding that the Pirates most certainly had a property right in the news of the games “for a reasonable time following the games” and that KQV’s nearly contemporaneous broadcasts amounted to unfair competition.34 The Pittsburgh club, “at great expense, acquired and maintains a baseball park, pays the players who participate in the game, and have, as we view it, a legitimate right to capitalize on the news value of their games by selling exclusive broadcasting rights.”35

KQV was given leave to appeal but the station ultimately settled the lawsuit, consenting to a permanent injunction and dropping its appeal in exchange for plaintiffs waiving their right to monetary damages.36 This ruling turned out to be a monumental win for local Pirates fans as Benswanger acquiesced and finally granted permission to KDKA and WWSW to broadcast home games, with the exception of Sunday and holiday contests.37 Broadcasts of Sunday and holiday games at Forbes Field were finally added in 1947.38

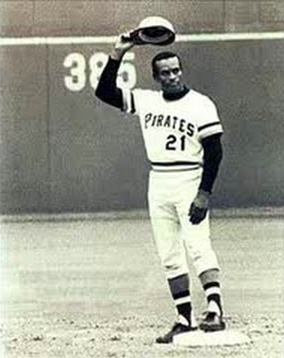

THE TRAGIC DEATH OF A PIRATE LEGEND AND GENUINE FOLK HERO

Pirates right fielder Roberto Clemente laced a double off of Mets pitcher Jon Matlack to reach the 3,000-hit milestone in his final regular-season at-bat on September 30, 1972. After closing out the season with a playoff series loss to the Cincinnati Reds, Clemente traveled to Nicaragua in November and managed the Puerto Rican All-Stars to a third-place finish in the Amateur Baseball World Series.39

Pirates right fielder Roberto Clemente laced a double off of Mets pitcher Jon Matlack to reach the 3,000-hit milestone in his final regular-season at-bat on September 30, 1972. After closing out the season with a playoff series loss to the Cincinnati Reds, Clemente traveled to Nicaragua in November and managed the Puerto Rican All-Stars to a third-place finish in the Amateur Baseball World Series.39

A 6.25-magnitude earthquake rocked Managua, Nicaragua, on December 23, 1972, causing widespread tragedy. An estimated 10,000 people died, another 40,000 were injured, and over 200,000 were displaced from their homes.40 In response, Clemente coordinated a momentous effort to provide emergency supplies to the victims, accumulating donations totaling $150,000, along with tons of food, clothing, and medicine.41

On December 30, 1972, Clemente went to see off what should have been the last of three relief supply flights. But the donations were so bountiful that Clemente had to arrange for yet another airplane to transport the remaining supplies to Managua. At the airport just outside of San Juan, Puerto Rico, Arthur Rivera approached Clemente and offered him the use of his DC-7 cargo plane to airlift the remaining relief provisions.42 Clemente inspected the plane and agreed to pay Rivera $4,000 (approximately $24,000 today) upon his return to Puerto Rico.43 Fatefully, Clemente decided to personally accompany this final delivery, believing that earlier shipments had fallen into the hands of profiteers.44

By law, Rivera was required to provide a pilot, co-pilot, and flight engineer for the flight. Rivera hired a pilot but appointed himself as co-pilot, despite his lack of certification to fly the DC-7. Rivera also neglected to hire a flight engineer.45

Unbeknownst to Clemente, Rivera’s DC-7 had been involved in an accident on December 2, when a hydraulic power loss caused the aircraft to leave the taxiway and crash into a water-filled concrete ditch.46 After the incident, the Federal Aviation Administration was advised and an inspector confirmed with Rivera that he intended to repair the plane. Thereafter, the damaged propellers were replaced and the engines were run for three hours, showing no signs of malfunction.47 The airplane was returned to service by the repairmen and no further inspection was conducted by the FAA prior to the ill-fated flight.48 In fact, the plane had not even been flown since its arrival from Miami in September 1972.

Rivera’s aircraft, fully loaded with cargo, crew, and Roberto Clemente aboard, was cleared for takeoff at 9:20 p.m. on December 31 with favorable weather and visibility at 10 miles. Upon takeoff, the plane gained very little altitude and at 9:23, the tower received a message that they were turning back around. Unfortunately, the aircraft did not make it back, crashing into the Atlantic Ocean about a mile and a half from shore.49 Everyone on aboard perished in the crash, including Clemente, just 38 years old.

Clemente’s wife, Vera Zabala Clemente, and the next of kin of the other passengers filed a lawsuit against the United States alleging that FAA employees were responsible for the fatal crash.50 Specifically, the plaintiffs claimed that the FAA breached its duty to promote flight safety by failing to revoke the airworthiness certificate of the DC-7 after the December 2 accident; monitor the repair process; discover that the plane was not airworthy; inspect for proper weight and balance; and screen for a qualified crew. It was the plaintiffs’ contention that if the FAA had acted in accordance with its own internal procedures—an order known as “Continuous Surveillance of Large and Turbined Powered Aircraft”—the plane would have been denied flight clearance, Clemente would have been advised of the deficiencies, and the tragic crash would never have happened.51

The United States countered that the FAA did not have any legal duty to “discover or anticipate acts which might result in a violation of Federal Regulations” and that there was no causal connection between the FAA’s inspection procedures and the fatal crash. Federal attorneys argued that the FAA’s conduct could be a legal cause of the accident only if it constituted a substantial factor in the crash and not mere speculation.52

The court scrutinized the FAA’s investigative report, which revealed that the fatal crash was caused by an engine failure exacerbated by the plane having been nearly 4,200 pounds over the maximum allowable gross weight at takeoff.53 The court held that the FAA had failed to exercise due care and violated its own rules.54 Because the flight crew was inadequate, the situation was such that “for all practical purposes the Captain was flying solo in emergency conditions.”55 Accordingly, the FAA’s failure to inspect and ground the plane “contributed to the death of the . . . decedents.”56

If the required ramp inspection had been completed by the FAA, the lack of a proper crew and overloading would have been discovered, Clemente would have been notified, and he would not have agreed to board the plane, thereby avoiding his untimely death.57 Under these circumstances, the court found in favor of Vera Zabala Clemente and the other plaintiffs on the issue of negligence.

The United States appealed the decision, claiming that the trial court erred in the finding of a duty on the part of the FAA.58 The critical question the appellate court was asked to address was whether the FAA staff in Puerto Rico had a duty to inspect the DC-7 and warn the decedents of “irregularities.”

The appellate court acknowledged that the Federal Aviation Act’s purpose is to promote air safety; however, this “hardly creates a legal duty to provide a particular class of passengers particular protective measures.” Further, the issuance of the “Continuous Surveillance of Large and Turbined Powered Aircraft” order was done gratuitously and did not create a duty to the decedents or any other passengers.

The appellate court ultimately held that the order created a duty of the local inspectors to “perform their jobs in a certain way as directed by their superiors.” The failure to comply with this order, however, did not create a cause of action based on negligent conduct against the FAA. Ultimately, the pilot-in-command has the responsibility to determine that an airplane is safe for flight and nothing in the FAA directives shifted the burden onto the federal government.59

Finally, the court found that there was no evidence that any of the deceased had relied on the FAA to inspect the aircraft prior to takeoff. Accordingly, the finding of negligence on the part of the FAA was reversed.60

The appellate court concluded, “The passengers on this ill-fated flight were acting for the highest of humanitarian motives at the time of the tragic crash. It would certainly be appropriate for a society to honor such conduct by taking those measures necessary to see to it that the families of the victims are adequately provided for in the future. However, making those kinds of decisions is beyond the scope of judicial power and authority. We are bound to apply the law and that duty requires the reversal of the district court’s judgment in favor of the plaintiffs.”61

The plaintiffs’ request that the case be heard by the United States Supreme Court was denied.62

CONCLUSION

Baseball is, as Justice Musmanno wrote in 1966, “an indispensably integral part of our municipal American way of life.”63 While baseball and American courtrooms have been inexorably linked since the earliest days of the game, these particular cases illustrate the lasting impact each has on us as fans. The Pittsburgh club is still called the Pirates, we are still prohibited from broadcasting accounts of games without the express written consent of Major League Baseball, and Roberto Clemente is fondly remembered both for his baseball prowess and his off-field compassion.

JOHN RACANELLI is a Chicago lawyer with an insatiable interest in baseball-related litigation. When not rooting for his beloved Cubs (or working), he is probably reading a baseball book or blog, planning his next baseball trip, or enjoying downtime with his wife and family. He is probably the world’s foremost photographer of triple peanuts found at ballgames and likes to think he has one of the most complete collections of vintage handheld electronic baseball games known to exist. John is a member of the Emil Rothe (Chicago) Chapter.

Notes

1 Conrad v. City of Pittsburgh, 421 Pa. 492, 508-509, 218 A.2d 906 (Pa., 1966).

2 “Baseball Notes,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, February 5, 1891.

3 Silver King was to report back to the St. Louis Browns, Charlie Reilly to the Columbus Solons, both of the American Association.

4 Dressed to the Nines: A History of the Baseball Uniform, an online exhibit produced by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Library, Cooperstown, NY; Pittsburgh Pirates 1912 page. http://exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org/dressed_to_the_nines/detail_page.asp?fileName=nl_1912_pittsburgh.gif&Entryid=197

5 Allegheny Base-Ball Club v. Bennett, 14 Fed. 257 (W.D. Pa., 1882)

6 “Von Der Ahe Swears Out a Warrant Charging Mark With Conspiracy,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, March 4, 1981.

7 “Baldwin’s Troubles,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 4, 1891.

8 “Von Der Ahe Sued,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), April 12, 1891.

9 “Tough on Chris,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 4, 1894; $10,000 in 1894 would be equivalent to about $287,500 in 2017. Inflation Calculator, https://westegg.com/inflation/.

10 “Tough on Chris.”

11 “Ball Tosser in Court,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, May 21, 1895; “Chris Makes an Appeal,” Pittsburgh Press, July 1, 1897.

12 “Von Der Ahe Wants a New Trial,” Chicago Tribune, January 22, 1897.

13 Baldwin v. Von der Ahe, 39 A. 7, 184, Pa.St. 116 (Pa., 1898).

14 “W.A. Nimick Sued,” Pittsburgh Press, August 2, 1897.

15 “Abducted by Force,” Sporting Life, February 12, 1898.

16 “Von Der Ahe is Kidnaped,” Topeka State Journal, February 8, 1898; “Abducted by Force,” Sporting Life.

17 “Abducted by Force.”

18 “In re Petition of Chris Von Der Ahe,” Pittsburgh Legal Journal, February 11, 1898, 269.

19 “In re Petition of Chris Von Der Ahe,” 270.

20 “In re Petition of Chris Von Der Ahe,” 267-270.

21 “The Baldwin Case,” Sporting Life, September 10, 1898.

22 “Pirates Finally Smoke Out Broadcast Secret of KQV,” Pittsburgh Press, July 14, 1938.

23 “Radio Suit Is Opened By Pirates,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 7, 1938. Additionally, Pirates road games against the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants were not authorized for broadcast; $17,500 in 1938 would be equivalent to about $310,000 in 2017. Inflation Calculator, https://westegg.com/inflation/.

24 “Pirates Finally Smoke Out,” Pittsburgh Press; “Pioneering Radio Men Broadcast Pirate Game ‘Over the Fence,’” Pittsburgh Press, April 27, 1947.

25 “Judge Gets ‘Knot Hole’ Radio Suit,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 27, 1938; “Court Bars ‘Knot Hole’ Broadcasts,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 9, 1938.

26 “Pirates Seek Ban on KQV as Baseball Broadcasters,” Pittsburgh Press, July 6, 1938; $100,000 in 1938 would be equivalent to about $1.77 million in 2017. Inflation Calculator, https://westegg.com/inflation/.

27 “Radio Suit Is Opened By Pirates,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 7, 1938.

28 “Pirates Seek Ban,” Pittsburgh Press.

29 “Pirates Finally Smoke Out,” Pittsburgh Press.

30 “Judge Gets ‘Knot Hole,’” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

31 National Exhibition Co. v. Teleflash, Inc., 24 F.Supp. 488 (SDNY, 1936). National Exhibition Co. was the legal name for the New York Giants.

32 National Exhibition Co. v. Teleflash, 489.

33 Pittsburgh Athletic Co., et al., v. KQV Broadcasting Co., 24 F.Supp. 490, 493 (W.D. Pa., 1938).

34 Pittsburgh Athletic Co., et al. 490, 492

35 Pittsburgh Athletic Co., et al. 492.

36 “Pact Ends Pirate Suit Against KQV,” Akron Beacon Journal, October 5, 1938.

37 “Pirates Finally Smoke Out,” Pittsburgh Press.

38 “Pioneering Radio Men,” Pittsburgh Press.

39 “Veteran Cuban Team Captures Amateur Title; U. S. Runner-Up,” The Sporting News, December 30, 1972.

40 “Quakes Kill Thousands in Nicaragua,” Pittsburgh Press, December 24, 1972.

41 “Clemente Dies in Plane Crash,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 2, 1973; $150,000 in 1972 would be equivalent to about $890,000 in 2017. Inflation Calculator, https://westegg.com/inflation/.

42 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 566 (D.P.R., 1976).

43 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 567 (D.P.R., 1976).

44 “Clemente, Pirates Star, Dies in Crash of Plane Carrying Aid to Nicaragua,” New York Times, January 2, 1973.

45 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 567 (D.P.R., 1976).

46 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 565 (D.P.R., 1976).

47 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 566 (D.P.R., 1976).

48 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 566, fn5 (D.P.R., 1976).

49 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 567 (D.P.R., 1976).

50 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 565 (D.P.R., 1976). The Federal Tort Claims Act is a limited waiver of sovereign immunity that authorizes parties to sue the United States for tortious conduct.

51 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 568, 570-571 (D.P.R., 1976). FAA regulation Order SO8430.20C called for “continuous surveillance of large and turbine powered aircraft to determine noncompliance of Federal Aviation Regulations.” Furthermore, a “ramp inspection” was required to determine whether the crew and operator were in compliance with the safety requirements regarding the airworthiness of the aircraft as to the weight, balance and pilot qualifications. Any indication of an “illegal” flight crew was to be made known to the crew and persons chartering the service. Finally, discovery of such noncompliance was to be given the highest priority by the FAA, second only to accident investigation.

52 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 569 (D.P.R., 1976).

53 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 567-568 (D.P.R., 1976).

54 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 575 (D.P.R., 1976).

55 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 570 (D.P.R., 1976).

56 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 576 (D.P.R., 1976).

57 Clemente v. United States, 422 F.Supp. 564, 571 (D.P.R., 1976).

58 Clemente v. United States, 567 F.2d 1140, 1143 (C.A.1 (Puerto Rico), 1977).

59 Clemente v. United States, 567 F.2d 1140, 1145, 1149 (C.A.1 (Puerto Rico), 1977).

60 Clemente v. United States, 567 F.2d 1140, 1148, 1151 (C.A.1 (Puerto Rico), 1977).

61 Clemente v. United States, 567 F.2d 1140, 1145, 1148-1149, 1151 (C.A.1 (Puerto Rico), 1977).

62 Clemente v. United States, cert. denied, 435 U.S. 1006, 98 S.Ct. 1876, 56 L.Ed.2d 388 (1978).

63 Conrad v. City of Pittsburgh.