Alex Johnson and Tony Conigliaro: The California Angels’ Star-Crossed Teammates

This article was written by Paul Hensler

This article was published in Fall 2023 Baseball Research Journal

When the American League expanded for a second time in 1969 and split into a pair of divisions, the California Angels could be excused for still thinking of themselves as an expansion team, since they had come into existence only eight years earlier. Over the course of this brief lifespan, the Angels had compiled a desultory track record, forging a won-lost record of 614–679 (with one tie), a winning average of .475.

Trying to establish themselves in Southern California while the specter of the Los Angeles Dodgers loomed large, the Angels had moved to new quarters in Anaheim in 1966. But when the Angels dropped to 67–95 in 1968, their poorest record to date, and began the divisional era by going 11–28, Bill Rigney was relieved of his duties as skipper. New manager Lefty Phillips tried to right the listing ship, winning 60 while losing 63 (with another tie) and bringing the Angels in at third place in the AL West, but 26 games behind the division champion Minnesota Twins. California had much work to do to become a contender.

Lackluster Angels production in 1968—the team outscored only the Chicago White Sox and came in seventh or eighth (out of 10 teams) in several other offensive categories—was eclipsed by even worse numbers in 1969: The Angels finished last (now out of 12) in runs scored, hits, doubles, home runs, walks, batting average, slugging percentage, on-base percentage, and on base-plus-slugging. Expansion-year pitching had delivered no advantage to California batters.

Over the next two seasons, general manager Dick Walsh used the trade market to try to fortify the weak Angels offense, and in the course of doing so brought together two compelling figures who, by their most recent performances, should have brought a new degree of potency to the Angels lineup. This essay will show how those players, Alex Johnson and Tony Conigliaro, in their individual ways, failed to build on the stepping stone of an ostensibly successful 1970 campaign.

TRYING TO IMPROVE: STEP 1

In late November 1969, Walsh acquired Johnson and utility infielder Chico Ruiz, a close friend of Johnson’s, from the Cincinnati Reds in exchange for three pitchers. Johnson’s early career showed glimpses of promise: Breaking in with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1964, he put up a .303/.345/.495 slash line in 43 games, for an OPS+ of 135. The following season he hit .293/.337/.443 over 97 games, an OPS+ of 120. But he had a track record as a poor defensive player, having committed 30 errors in 321 games in the minors. Johnson confessed to being jittery when in the outfield, and although his work with the glove got better, his “perceived lack of effort and poor attitude” grated on Phils manager Gene Mauch, and in late October 1965 the outfielder was packaged in a trade to the St. Louis Cardinals.1

Johnson did little to distinguish himself in his early tenure with his new team, batting only .186 before being sent to Triple-A Tulsa in mid-May 1966. The following season, in which St. Louis ultimately captured the World Series, the right-handed Johnson was platooned in right field with newly acquired Roger Maris, but Johnson again faltered while playing in only half of the regular-season games and accumulating just 39 hits in 175 at-bats for a .223 average, one home run and an anemic 68 OPS+.

As his malcontent behavior became more of a detriment to the team, the 25-year-old once more was on the trading block. “We tried everything to bring out his potential,” said an exasperated Dick Sisler, the Cardinals hitting coach.2 This time he was dispatched to the Cincinnati Reds.

Upon his 1968 arrival at Crosley Field, Johnson transformed from bust to boom, with Reds manager Dave Bristol seeming to be the reason for the turnaround. Rather than nagging his temperamental player about his comportment, Bristol was content to leave Johnson to his own devices. Johnson became the everyday left fielder, appearing in 149 games and contributing a .312/.342/.395 line (116 OPS+), with little power but 16 stolen bases, earning him Comeback Player of the Year honors from The Sporting News, although Breakout Player of the Year would have been a more appropriate label.

As if to prove his rightful place as a prime-time player, Johnson improved in every meaningful offensive category in 1969, including 17 home runs, more than twice his previous career high. But just as the Reds were about to emerge as the Big Red Machine under new manager Sparky Anderson in 1970, their outfield became crowded with prospects Hal McRae and Bernie Carbo, who could platoon in left field. That made Johnson expendable. The Angels anticipated his production would continue to trend upward.

Phillips’s first full year at California’s helm was infused with a modicum of hope: The Angels had equaled their young franchise record of 86 victories in 1970 and resided in second place for most of the season before settling into third on Labor Day. By remaining within hailing distance of the Twins, who would repeat as division winners, California could lay claim to status as contenders in the AL West. However, this joy and optimism were tempered by the baggage that accompanied the acquisition of Alex Johnson.

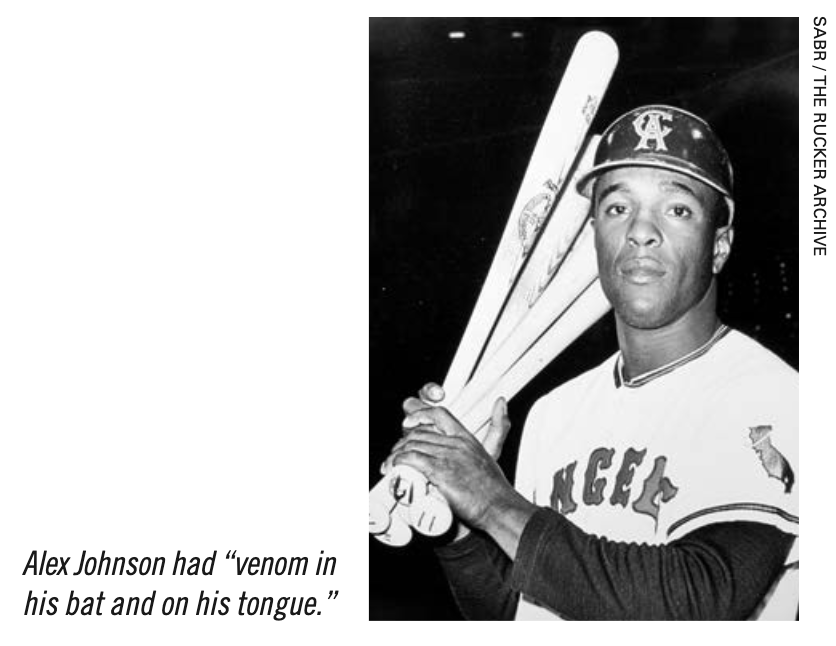

While the Angels were pleased with the statistics generated by their new left fielder in 1970—named to the American League All-Star team, Johnson had his best offensive season and won the league batting title (by a whisker over Carl Yastrzemski) with a .329 average—his brooding and moodiness never deserted him. The enigmatic player was fined for lack of hustle, and while he led the Angels by grounding into 25 double plays, some of these may have been the result of his batting in the heart of the order. (Recall that Jim Rice of the Boston Red Sox led both leagues in GIDPs for four straight years in the 1980s.) He yelled at teammates and reporters who attempted to engage him in conversation. “There is venom in his bat and on his tongue,” noted The Sporting News of Johnson’s hitting ability and demeanor. His actions became an increasingly serious distraction.3

For his part, Phillips was held in high regard for somehow weathering the storm swirling around Johnson. The manager was credited with working psychological wonders in stroking the egos of several of his players who needed coddling, and although Phillips was quick to deflect the praise directed his way, the results, in the AL West standings and in Johnson’s performance at the plate, more than hinted at Phillips’s ability to hold up in a difficult situation. By writing Johnson’s name in the cleanup slot and leaving him in the game rather than replacing him with a late-inning defensive outfielder, Phillips gave Johnson much latitude in the hope of letting the ends of his production justify the means.

But as the summer of 1970 progressed, Johnson was trying the patience of too many of his teammates and, ultimately, his manager. Club officials worried over the negative impact that Johnson might have on younger players who would be better served by a more appropriate role model. According to The Sporting News, “His recent taunting of an Angel pitcher nearly precipitated a clubhouse free-for-all,” and “acknowledging his malevolent disposition, his wife, Julia, has apologized to the other Angel wives for the way her husband treats their husbands.”4

By season’s close, it seemed a miracle that California forged the win total it had reached. In the final weeks of September, Johnson and Ruiz “exchanged words and punches in a brief skirmish at the batting cage. … This outburst followed a reported melee of the previous night that left the clubhouse in disarray.”5 Through all this turbulence, Johnson was documenting his plight so that he could take his own complaints to the Major League Baseball Players Association, whose director, Marvin Miller, later observed, “Two things became quite clear. Many of Johnson’s grievances were legitimate, and he had serious emotional problems.”6

Turning the corner of the disruptive campaign, the Angels, on paper at least, possessed the means to build on their success. Yet the stat sheet failed to account for all the characteristics of what underpinned the roster and contributed to—or detracted from—the chemistry among the players and their relationship with the manager. And with the book barely closed on the 1970 season, Dick Walsh was already at work to add more power to the lineup, sending three players to the Red Sox for catcher Jerry Moses, pitcher Ray Jarvis, and outfielder Tony Conigliaro.

TRYING TO IMPROVE: STEP 2

“Tony C,” as Conigliaro was affectionately known to hometown fans, was the embodiment of a local kid made good. A native of Revere, Massachusetts, he burst onto the scene in 1964 as a 19-year-old who slugged 24 home runs and then led the American League in that category the next year with 32. With handsome looks to boot, Conigliaro also was a budding pop singer, with several recordings on the RCA label to his credit by early 1965. He had the world as his oyster even though he was playing for a team that was less than mediocre, the BoSox finishing ninth in the American League in 1966. As his power numbers continued to draw attention, he became the second-youngest player to belt 100 career homers, achieving the mark in July 1967, but as a batter who crowded the plate, he missed playing time due to HBP-related injuries that included broken bones in his left arm and wrist.

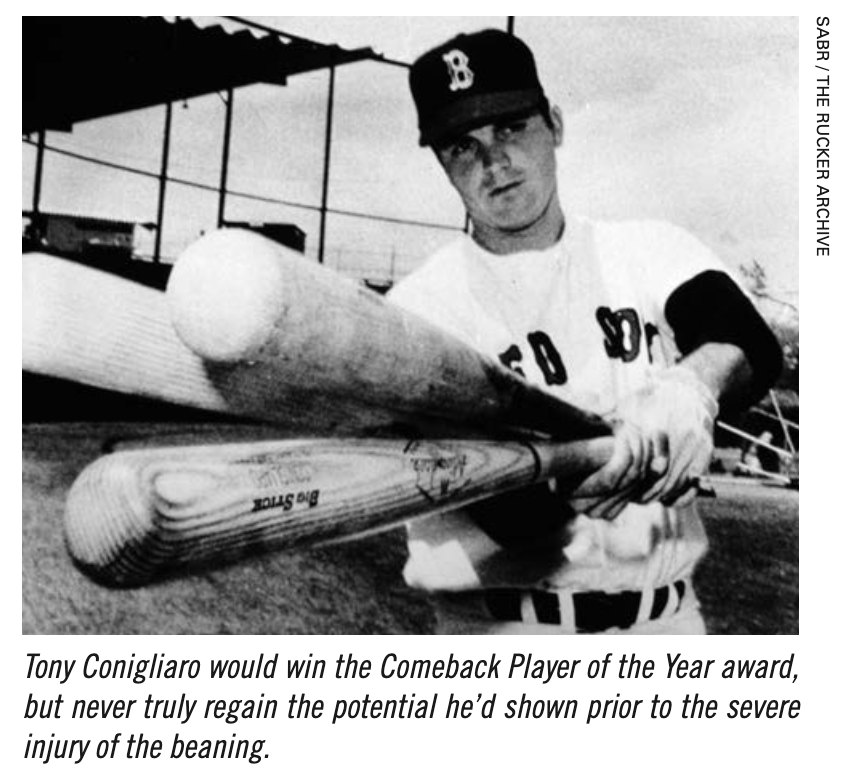

When Boston made an unexpected challenge for the AL pennant in 1967, Conigliaro was prominent in the lineup, batting cleanup for rookie manager Dick Williams’s “Impossible Dream” team and earning a berth on the AL All-Star squad. But the outfielder would not be on hand to relish the pennant that the Red Sox eventually captured: He was beaned on the evening of August 18 in a game against the Angels at Fenway Park. Hit in his left eye by a Jack Hamilton pitch and suffering a broken cheekbone, Conigliaro was relegated to the sidelines with the fear that he might lose sight in the eye, and his rehabilitation would cost him the entire 1968 season.

Diligence and persistence paid off for Conigliaro in 1969, when he earned AL Comeback Player of the Year honors. In 141 games, he tallied a modest .255 batting average but showed that his ability to hit the long ball remained in his arsenal, stroking 21 doubles and 20 home runs while driving in 82 runs, though his triple slash line of .255/.321/.427 and his OPS+ of 103 were all a big step down from his peak years in Boston. An even brighter season in 1970—“with one good eye,” according to Conigliaro’s biographer, he batted .266 in 146 games, with 36 home runs and 116 RBIs—seemed to lay to rest any doubts about his hitting ability, if not his recovery.7

But fourth- and third-place finishes in 1968-69 cost Williams his job, and the manager was rankled by strife in the clubhouse and by Conigliaro’s tendency to enjoy the nightlife. Friction between management and a few notable mainstays, among them Reggie Smith and George Scott, eventually led to the trades of several players, but Tony C’s circumstances were peculiar in their own way. Shortstop Rico Petrocelli said that Conigliaro “wanted to be treated like a superstar. It was his hometown. … He felt he should have been the guy, the man.”8

An internecine imbroglio between Smith, Red Sox newcomer Billy Conigliaro—Tony’s younger brother—and Yastrzemski, was the source of much angst. As the Sox elder statesman at the age of 30, Yaz incurred the wrath of Boston fans when the team foundered early in the 1970 season, and the former Triple Crown winner was accused of cultivating too personal a relationship with Boston owner Tom Yawkey.9

In the wake of the 1970 season, the Red Sox sought to address shortcomings with their pitching staff and pulled off several trades that allowed them to deal away some of their surplus offensive power. One of the prime subjects sent packing was Tony Conigliaro. His trade to the Angels provoked a firestorm of protest from Boston fans. “It was, however, a trade that took advantage of Conigliaro’s post-beaning value at the time it had peaked,” in the view of one baseball historian. Another opinion had it that Yastrzemski was a driving force behind getting his fellow outfielder off the Boston roster.10

Still cautiously optimistic about furthering what they had accomplished in 1970, the Angels were hoping that Conigliaro’s bat would bolster their offense— if, that is, he could overcome the shock of being let go by his now former team. There may have been some reactionary enthusiasm on the part of the Angels in response to the crosstown Dodgers’ acquisition of Dick Allen, who arrived via trade on October 5, 1970, from the St. Louis Cardinals. Six days later, the Angels countered with an exchange that gave them their own high-profile slugger.

Conigliaro’s new club exuded such confidence in him that his visage appeared on the cover of the Angels’ 1971 media guide along with the team’s three other headliners from the previous season: Clyde Wright, Jim Fregosi, and Alex Johnson. Even his mellifluous nickname, “Tony C,” graced the back of his road uniform instead of the traditional last name reserved for that spot. In its preview of the coming season, The Sporting News touted the outfield of Johnson, Conigliaro, and newly added Ken Berry as “the best in [the] club’s history.”11 So, what was not to like about the team’s prospects in the new year?

For one thing, the Angels finished spring training with an uninspiring 10–15 record, and Johnson had already been fined and pulled in the first inning of one contest for failing to run out a groundball. He was giving no indication of any change to his work ethic or improvement in his play in the outfield.

As Johnson perpetuated his annoyances, Conigliaro was settling in quite nicely in the sunny environs of Southern California. He worked to cultivate a cordial relationship with the local press, continued to appear as a singer, dreamed of a future in Hollywood movies, and picked up extra cash through commercial endorsements. That his next-door neighbor was Raquel Welch only burnished the luster of his new venue. Conigliaro’s reported $76,000 salary and the Cadillac El Dorado he drove were other perks that he enjoyed as the hero in search of something to conquer.

But for all the material trappings Conigliaro enjoyed, the real harbinger of his days as an Angel may have been the weak .186 batting average he compiled in spring camp as well as playing time missed due to back spasms and flu. More ominously, the closeness of family that underpinned his life in Boston was no longer available to him, his father Sal and brother Billy still ensconced back East. Though Tony worked hard as a professional ballplayer, “He was the new kid in the neighborhood. … He needed to win everyone over with baseball heroics.”12 This was a tall order considering that the fans at Anaheim Stadium were generally less passionate about their team than the denizens of Fenway Park.

FOR WANT OF A SPARK

As the 1971 season began, the confluence of Johnson and Conigliaro did not deliver the offensive punch the Angels had hoped for. The former hit decently, though not of batting-title quality, but the home fans persisted in vocalizing their displeasure with choruses of boos. The latter seemed destined for alienation from his teammates because of various ailments or inauspicious conditions, ranging from discomfort with his injured eye, which he attributed to the brightness of the West Coast sun, to pains in his neck, legs, and back. Pitcher Tom Murphy noted that the right fielder “always seemed to be hurt,” but Conigliaro wanted to dispel the notion that he was seldom up to the task, and, unlike Johnson, he strove to improve his defensive play so that center fielder Berry, already famed for his glove work, would have fewer worries.13

Through the first three months of the season, Conigliaro played in an average of 22 games each month but missed 15 contests. His batting average peaked at .264 in mid-May, but the power stroke that had been his signature was in short supply. California’s mediocre standing in the AL West in the early going was due in large part to the quality of its pitching, which ranked in the middle of the league, whereas the offense was second from the bottom.14

Conigliaro’s name never appeared on the disabled list, but an unwelcome amount of tarnish was accumulating on his reputation because of the time he was unavailable. Despite receiving numerous shots of cortisone for relief of back pain, Conigliaro could not convince his teammates of his woes. They took an increasingly dim view of what they were starting to believe was more hypochondria than the impact of actual injuries. Clubhouse pranksters greeted Conigliaro in early June with a display comprising “a stretcher set up in front of his locker with his uniform spread out on it and a pair of crutches wrapped in Ace bandages forming a coat of arms.”15 Offended by the exhibit, which was soft-pedaled by manager Phillips as just mischief that ballplayers perpetrate, Conigliaro retreated, fittingly enough, to the sanctity of the trainer’s room. None of his teammates had endured the near-fatal episode of being hit in the head and worked so diligently to return to the game, and it was impossible for any of them to understand his circumstances.

Try as he might to regain the form he displayed in 1970, Conigliaro only struggled more and found that his fellow Angels were labeling him a slacker. About the only persons in whom he could confide were Jerry Moses, the catcher who had accompanied Conigliaro in the trade from Boston, and, curiously, Johnson. The defending batting champion shunned the press for the most part, and he continued to exasperate his manager with aloof and indifferent play, yet Johnson now found a sympathetic companion in Conigliaro. It may well have been that the Angels were leading the league in malcontents, and this was prior to the Oakland Athletics gaining distinction as a team whose clubhouse became branded with its own infighting.

Early in the season, Johnson agreed to an interview with a new publication, Black Sports magazine, and in his conversation with journalist Bill Lane, he chided fans who reveled in booing him yet would instantly begin cheering him with the next base hit. Johnson, an African American from Detroit, confessed that some of his white teammates “get along with him very well,” but he was blunt in his assessment of the differences between the races. “I’ve been bitter ever since I learned I was Black. The white-dominated society into which I was born, in which I grew up and in which I play ball today is anti-Black. My attitude is nothing more than a reaction to their attitude. … The white society actually rejects the Black in everything. What we often take for true equality is smiling toleration.”16 Johnson had to have felt some degree of comfort in speaking freely to a reporter likely with a sympathetic ear.

As the 1971 season progressed, Angels players and team management found themselves in an increasingly untenable position. In trying to tolerate Johnson’s behavior, Phillips alternated between fining and benching the outfielder, then reinstating him, all to no avail as the half-hearted base-running and loafing after fly balls continued. Frustrated teammates—Berry and Wright in particular—wearied of trying to reason with Johnson and nearly touched off locker-side brawls. Ruiz, who “had an agreeable personality and was well-liked by … teammates and opponents alike,” as well as a lengthy and close relationship with Johnson, became the focal point of a notorious incident in which the infielder allegedly pulled a gun on Johnson in the clubhouse.17

Press photos of Johnson sitting alone on the dugout bench told the sad story of a man ostracized by those with whom he should have been relishing the opportunity and privilege of playing baseball at the highest level. Instead, the problem continued to fester as long as Johnson remained a member of the club.

An end of the tribulations was believed to be in sight when GM Walsh thought he had a deal worked out with the Milwaukee Brewers. Johnson would be traded for outfielder Tommy Harper. But when the latter’s bat showed signs of emerging from a lengthy slump as the mid-June trade deadline approached, the Brewers nixed the transaction.

Johnson played his last game for California on June 24. The Angels suspended him for 30 days without pay beginning in late June, and the expiration of that penalty dovetailed into his placement by commissioner Bowie Kuhn on the restricted list. Johnson’s case was taken up by the players’ union, which filed a grievance to be submitted to arbitration. In a Sports Illustrated profile that ran shortly after Johnson’s suspension began, the outfielder fingered Ruiz as “the cause of the dissension,” but the magazine placed blame in the most obvious place, citing “Johnson’s curious rebellion” and a “mockery of the game that cut his fellow players doubly deep. In a world of performance, to refuse to perform seemed to make fools of those who did, seemed to make nonsense out of the pure patterns of the game they played.”18

Dick Miller later reported in The Sporting News, “The number of fines and Johnson’s behavior, it was contended, should have indicated to General Manager Dick Walsh and Manager Lefty Phillips that Johnson was under extreme mental distress.” The final tally for the season came to 29 fines totaling $3,750.19 The adjudication of the grievance, however, came out in Johnson’s favor.

MLBPA director Marvin Miller, who was on the front line of Johnson’s defense, said, “I think it’s fair to say that most of the Angels didn’t grasp the depths of Johnson’s psychological problems.”20 Subsequent examinations by a pair of psychiatrists confirmed Johnson’s compromised mental state, and he won his case, as arbitrator Lewis Gill found that the player’s condition warranted a spot on the disabled list rather than a disciplinary suspension. The financial payout would be back salary minus the amount of the fines imposed by the ballclub, and Johnson was given a new home on October 5 when he and Moses were traded to the Cleveland Indians.

For Conigliaro, his ignominious finale came on July 9 in a marathon, 20-inning game at Oakland, when he went hitless in eight trips to the plate, including five strikeouts, yet these few statistics hardly tell the full story. A prelude occurred in the 11th inning when he fanned on a pitch that eluded the catcher, but with first base occupied and less than two outs, Conigliaro was automatically out. Still, he irrationally ran to first and argued with the home plate umpire about the play. Eight innings later came the ugly coda: Upon striking out after an unsuccessful bunt attempt—even trying after the bunt sign was removed with two strikes—Conigliaro “exploded” at plate ump Merle Anthony, who walked away to avoid worsening the confrontation. When the outfielder removed his batting helmet and swatted it fungo-style toward first base, he was ejected from the game, but not before“heav[ing] his bat over [first base umpire George] Maloney’s head.”21

Frustrated at losing 1–0 in the wee hours of the morning, Phillips grumbled to the press about Conigliaro’s actions, which exacerbated a deteriorating situation. The manager complained about his player’s lack of knowledge of the rules and his penchant for ignoring signals from the dugout, but then Phillips stunned the gathering by saying, “The man belongs in an institution.”22

Phillips’s blunt opinion was followed mere hours later by Conigliaro’s departure from the team. The embattled player confessed that headaches, coupled with vision that never fully recovered after his August 1967 beaning, had rendered him a shell of the player he had once been. Conigliaro’s emotional outburst was a sad denouement, and he immediately retreated to the safety of his home turf and family in Boston.

Conigliaro referred to his exit as a retirement, and with Johnson still suspended, one might have believed the air to be clearer for the California roster. But the Angels played roughly .500 ball for the remainder of the season—they went 36–37 after the late-inning meltdown on July 9—and fell to fourth place in the AL West, leading to the predictable dismissal of Phillips and his coaching staff.

As Johnson had filed a grievance over his treatment by the ballclub, so too did Conigliaro, who, after originally acknowledging that he was forfeiting about half of his salary by retiring, revived the claim that since a medical condition had forced him from the game, he was entitled to $30,000, which was eventually paid by the team.

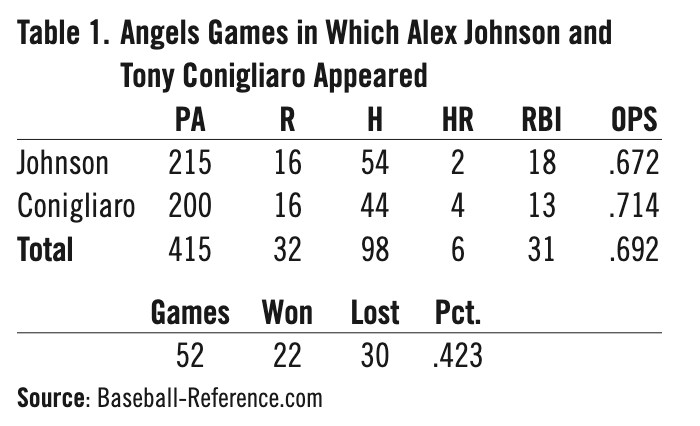

Speculation in The Sporting News about the 1971 Angels having one of their best outfields ever had been predicated on the anticipated synergy created by the defending AL batting champion followed in the batting order by a power hitter who, to all appearances, had overcome his eyesight issue. Yet their statistics and the team’s won-loss record show that no chemistry emerged from this pairing, whether in the form of enhanced individual performance or in the club’s ability to gain in the standings.

Johnson hit third in the order, where he remained for most of the games in which he played; Conigliaro started out in the cleanup slot, but as ailments took their toll, he was dropped to sixth. In some instances, the pair were in the same contest only because one of them appeared as a pinch-hitter or a late-inning replacement. In any case, a combined batting average of a tepid .263 with an accompanying RBI total that would project to merely 50 (based on a 600 at-bat season) was not what the Angels had anticipated.

There is a curious intersection of what was acknowledged as Johnson’s “emotional illness,” in Miller’s words, and the dismissive comment by Phillips about Conigliaro being ripe for institutionalization. Through the 1970s, it was not uncommon in public discourse to hear references to “mental retardation,” “funny farm,” or other unkind vernacular related to behavioral issues; an editorial in The Sporting News went so far as to diagnose Johnson as “a social schizophrenic.”23

Thankfully, modern sensibilities and better medical knowledge have come to recognize behavioral illnesses that can be treated by trained professionals who today are better equipped—and supported by the general public—than they were decades ago. For example, yesteryear’s “shell shock” is better understood today as post-traumatic stress disorder. Johnson and Conigliaro’s respective circumstances—behavioral in the case of the former, behavioral (to a lesser degree) and the difficulties of recovery from a ghastly head injury for the latter—demand our attention and understanding.

SUMMARY

Through the vicissitudes of the baseball world, two All-Star players were paired up in the corners of the 1971 California Angels outfield, and optimists among baseball observers could only dream of the possibilities. That Johnson and Conigliaro both departed by midseason only adds to the intrigue, and their exits created a void similar to when a conflict ends: Peace has been achieved, but the effects fail to dissipate quickly. Picking up the pieces of a shattered campaign, the Angels won about half of their remaining games beyond early July, but the “one step forward” taken by the club in 1970 clearly yielded to “two steps back” by the end of the following season. Even the appointment of a new GM, Harry Dalton, whose success with the “Oriole Way” in building Baltimore as the most formidable team of the late 1960s and early 1970s set the standard of the era, could not correct the course of a franchise steeped in mediocrity.

Granted that the issues faced by California were deeper than the shortcomings of two outfielders upon whom so much rested. But there were lessons to be learned by the time Alex Johnson won his grievance case: Emotional issues, unremittingly part of the human condition, should not be given short shrift; and players suffering from physical injuries, especially the type of damage from one of the worst head injuries ever sustained, may likely endure long-term complications and perhaps only experience a tentative recovery.

It is to his credit that Johnson continued to play for several more years beyond his pair of volatile seasons with the Angels and that Conigliaro also persisted beyond August 18, 1967, a date after which his baseball career would be forever marked as a comeback. For the few months of 1971 when they both wore Angels uniforms, the bats of Johnson and Conigliaro yielded unremarkable production rather than the expected one-two punch, and their departures created the challenge for Dalton of having to fill a pair of vacancies in the outfield and in the heart of the California batting order.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the peer reviewers and editor King Kaufman for their suggestions and work on this essay.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the endnotes, the following were also used:

Baseball-Reference.com

1971 California Angels News Media Guide

The Sporting News

Bill Nowlin, “Tony Conigliaro,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/tony-conigliaro/.

Jeff Pearlman, “Catching Up With … Alex Johnson, Angels Outfielder,”

Sports Illustrated, March 9, 1998.

Daniel E. Slotnik, “Alex Johnson Dies at 72; Deft Batter Won a Key Ruling,”

The New York Times, March 5, 2015.

Notes

1 Mark Armour, “Alex Johnson” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/alex-johnson/, accessed May 15, 2023. (Emphasis added.)

2 Armour, “Alex Johnson.”

3 John Wiebusch, “Don’t Try to Chat with Alex—Just Let Him Hit,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1970.

4 Ross Newhan, “Alex of Angels Is Falling from Realm of Glory,” The Sporting News, August 15, 1970.

5 Newhan, “A Lot of Wrongs Dot Wright’s Leap to 20,” The Sporting News, October 3, 1970.

6 Marvin Miller, A Whole Different Ball Game: The Sport and Business of Baseball (New York: Birch Lane Press, 1993), 135.

7 David Cataneo, Tony C: The Triumph and Tragedy of Tony Conigliaro (Nashville: Rutledge Hill Press, 1997), 190.

8 Cataneo, Tony C, 190.

9 Bill Nowlin, Tom Yawkey: Patriarch of the Boston Red Sox (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018), 289.

10 Nowlin, 288; Cataneo, Tony C, 193.

11 C.C. Johnson Spink, “Spink’s Forecast: Orioles and Dodgers to Win,” The Sporting News, April 10, 1971.

12 Cataneo, Tony C, 198.

13 Cataneo, Tony C, 198.

14 American League batting and pitching statistics, The Sporting News, July 12, 1971.

15 Cataneo, Tony C, 200. The tasteless addition of ketchup-stained sanitary napkins also was part of the scene.

16 Bill Lane, “Alex at the Bat,” Black Sports, July 1971. This publication was ahead of its time: Not until well into the 21st century was “Black” capitalized in the mainstream media.

17 Jerome Holtzman, “’71 Saw Gate Up, Short Move, Alex Angry,” in Paul MacFarlane, et al, Official Baseball Guide for 1972 (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1972), 281.

18 Ron Fimrite, “For Failure to Give His Best.,” Sports Illustrated, July 5, 1971.

19 Dick Miller, “Johnson Fined 29 Times 19 in ’71; Total: $3,000,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1971, 32; Armour, “Alex Johnson.”

20 Marvin Miller, A Whole Different Ball Game, 137.

21 Cataneo, Tony C, 201-02.

22 Cataneo, Tony C, 202.

23 “Better to Fight Than to Talk,” The Sporting News, July 31, 1971.