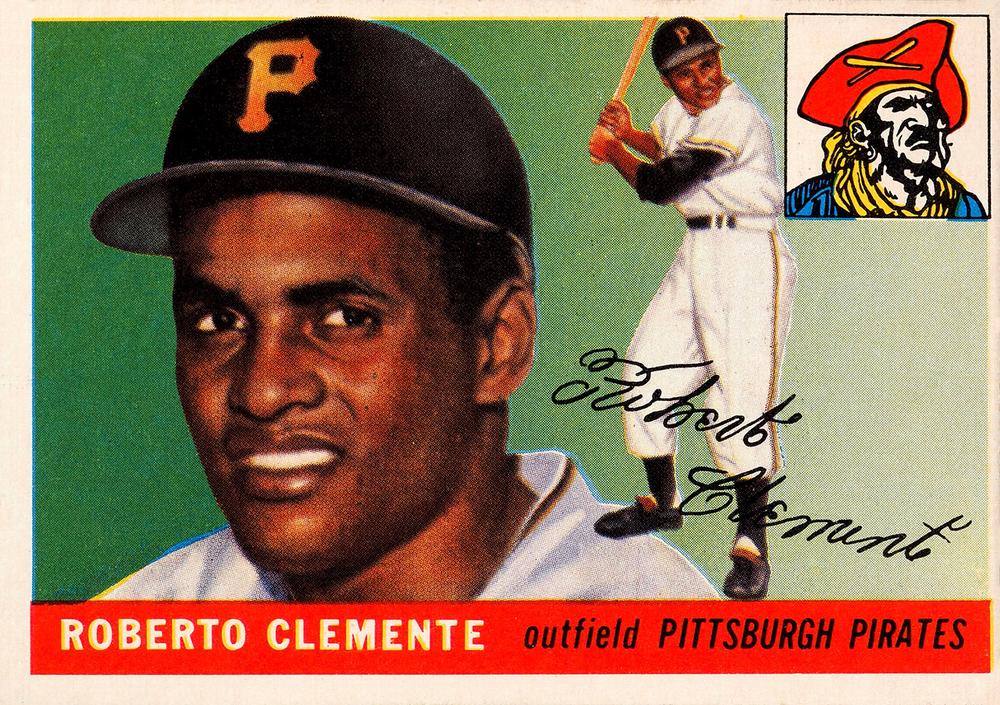

‘All He Required of a Baseball Was That It Be in the Park’: Roberto Clemente’s Offensive Skills

This article was written by Mark Davis

This article was published in ¡Arriba! The Heroic Life of Roberto Clemente (2022)

“In all due respect to Henry Aaron, Stan Musial and Willie Mays, the best hitter I ever played against was Roberto Clemente.”— Pete Rose, recipient of the 1976 Roberto Clemente Award1

The baseballs are signed by Bob Gibson, Steve Carlton, Ton Seaver, Ferguson Jenkins, Don Drysdale, and Sandy Koufax – each one a Hall of Fame pitcher against whom Clemente hit .300 or higher. (Photograph by Duane Rieder.)

Roberto Clemente’s offensive accomplishments should leave zero doubt as to the merits of his special election to the Hall of Fame in 1973: a career batting average of .317; four National League batting titles (1961, 1964, 1965, and 1967); the 1966 National League Most Valuable Player Award (he batted .317 with 29 home runs and 119 RBIs); the 1971 World Series MVP; the 11th player to have 3,000 regular-season hits; and only the second player to hit in every game of two consecutive World Series appearances (1960 and 1971).

Despite these achievements, Clemente’s offensive talent could be viewed as underappreciated by those who have cited his 240 regular-season home runs as a somewhat muted offensive record compared with other elite players of his era. He topped the 20-home-run mark just three times, for instance. Clemente for his part acknowledged this criticism throughout his career. “I can hit with anybody,” he insisted. “I believe I’m as good a hitter as Willie Mays or Henry Aaron. My only drawback is lack of home run power.”2 (Aaron hit 755 home runs and Willie Mays hit 660.)

A closer examination of Clemente’s offensive production reveals that he was arguably one of most intelligent hitters of his era. He demonstrated raw offensive power and was able to adjust his batting approach according to in-game circumstances. Simply put, Clemente could not only hit, but hit with power.

THE EARLY YEARS

Clemente’s first playing experience occurred when he joined his local slow-pitch softball team in 1942, and taught himself the basics of hitting with a guava tree limb that served as his first bat.3 He quickly fell in love with the game and spent hours on the neighborhood softball field, noting in his diary that he once hit 10 home runs during a marathon game.4 Clemente next progressed to fast-pitch softball, where in 1952 his strong fielding skills and ability to consistently pull the ball led to an invitation to a tryout co-hosted by the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Santurce Cangrejeros at Sixto Escobar Stadium in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Of the 72 players attending the tryout, Clemente was the only one to attract the interest of Dodgers scout Al Campanis. Impressed with his defensive abilities, Campanis invited Clemente to hit batting practice. Clemente did not disappoint. “The kid swings with both feet off the ground and hits line drives to right and sharp ground balls up the middle,” marveled Campanis. “He was the greatest natural athlete I have ever seen as a free agent.”5 Campanis also rated Clemente’s hitting power as “A+” in his scouting report.6 Despite this strong interest, major-league rules dictated that Clemente could not sign with the Dodgers until his 18th birthday. However, the Dodgers’ co-host, the Santurce Cangrejeros, wasted little time signing Clemente to a contract to play in the Puerto Rican Winter League.

Buster Clarkson, as the Cangrejeros’ manager and Clemente’s first skipper in professional baseball, recognized his raw offensive talent and made sure he was offered a similar amount of batting-practice pitches as his teammates.7 Clemente credited Clarkson with helping him improve his batting stride toward the pitcher, thus increasing his offensive production. Of Clemente, Clarkson noted, “[His batting stance] had a few rough spots, but he never made the same mistake twice. He was baseball savvy.”8

Clemente signed with the Dodgers a year later for a $10,000 salary and a $5,000 signing bonus. The Dodgers sent him to their International League affiliate in Montreal for the 1954 season, which meant that he became eligible to be claimed by another organization via a supplemental draft at season’s end.

Clemente saw limited playing time during the first half of his only season in Montreal. His manager, Max Macon, claimed this was due to Clemente’s free-swinging nature at the plate. “If you had been in Montreal that year, you wouldn’t have believed how ridiculous some pitchers made him look.”9 Despite limited playing time, Clemente showed flashes of offensive power. On July 25 he slammed a pinch-hit home run in the bottom of the 10th to win the first game of a doubleheader at home vs. the Havana Sugar Kings. The ball sailed over the 340-foot left-field fence and left the ballpark. “Clemente is a player with potential greatness,” wrote one reporter. “His clout over the left field wall … won the opening game Hollywood style.”10

FROM A YOUNG “BUC” TO “THE GREAT ONE”: 1955-1972

After being claimed by the Pirates in the November 1954 supplemental draft, Clemente made his major-league debut the following spring. The 1955 season also showcased Clemente’s unorthodox batting style, which was partly in response to a back injury sustained in an offseason car accident in Puerto Rico.11 This approach at the plate quickly caught the attention of teammates and reporters. “He stood at the batting cage, his head rolling as he jerked his neck in a series of exercises.… The posture was awkward. The swing was sudden and appeared unpremeditated.… Only after the bat strikes the ball is it obvious that this is a good hitter.”12

Clemente hit his first big-league home run on April 18, 1955, against the New York Giants. He hit the ball 450 feet to left-center field off the bullpen at the Polo Grounds (which was located in fair territory), and legged out an inside-the-park home run.13 A few weeks later, on June 5, while facing the Cincinnati Reds at Pittsburgh’s cavernous Forbes Field, Clemente hit a triple to dead center field that “must have traveled 450 feet in the air and would have been a homer in any National League park except Forbes Field and the Polo Grounds.”14

Clemente’s willingness to hit almost any pitch proved to be one of his strongest offensive abilities. He had only 18 walks in 501 plate appearances in 1955 and just 13 walks in 572 plate appearances in 1956. This led Clemente to develop a reputation that “he hit everything that didn’t hit him first.”15 Indeed, opposing managers told reporters they instructed their pitchers to give intentional walks to Clemente, but on many occasions he would swing at the pitches for base hits.16 Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Don Sutton once remarked of Clemente, “Anything between the on-deck circles was a strike to him. I’ve seen him double on knock-down pitches.”17

Interestingly, 2,154 (or 72 percent) of Clemente’s 3,000 hits were singles. That high a percentage could be considered a misleading indicator of a lack of home-run power, as Clemente showed he could crush hits that didn’t clear the outfield wall at Forbes Field. During a game against the Cincinnati Reds at Crosley Field on June 13, 1963, Clemente launched a pitch more than 400 feet; it was hit so hard to the wall that it quickly bounced to Reds’ center fielder, Vada Pinson, who quickly relayed the ball back to the infield, “restricting Clemente to a laser single.”18

On occasion, however, the baseball gods granted Clemente a trip around the bases for his line- drive efforts, such as on May 11, 1957, when Clemente scorched a hit over the head of Philadelphia Phillies center fielder Richie Ashburn. The ball rolled to the batting cage, which was stored in fair territory in deepest center field. When Ashburn finally got to the ball, Clemente was already at third base, and he scored easily for an inside-the-park home run.19

While Clemente is perhaps best known for hitting bullet line drives, he also hit monstrous home runs that left his fellow players speechless. In the first game of a doubleheader at Wrigley Field on May 17, 1959, Clemente hit a moon shot off Cubs pitcher Bob Anderson to deep right field, estimated at a minimum distance of 500 feet in negligible wind conditions. The Cubs hitting coach, baseball legend Roger Hornsby, remarked that it was the longest home run he had ever seen.20

Neither the daunting dimensions of Forbes Field nor the pressure of facing one of the National League’s greatest pitchers intimidated Clemente. On May 31, 1964, he led off the bottom of the third inning by launching a pitch from Sandy Koufax that hit the light tower in left-center field, an estimated 450 feet from home plate. Koufax said the ball was still rising when it hit the tower, which suggests it would have gone even farther with no resistance.21 Koufax later summarized his career facing Clemente as a sort of puzzle: “There is just no way you can develop a pitching pattern for him.”22

Clemente also harnessed his power to carry the Pirates offense when necessary, such as on May 15, 1967, vs. the Cincinnati Reds. In one of his best run-producing games, Clemente had three home runs and a double and drove in all of Pittsburgh’s runs in an 8-7 loss. “It was almost like Roberto Clemente playing the Reds all by himself and coming so close to wrecking them single-handedly,” a sportswriter observed.23 Clemente, much to his modest nature, downplayed his performance. “Yes, my biggest game, but not my best game,” he said. “My best game is when I drive in the winning run. I don’t count this one, we lost.”24

When Clemente arrived in the big leagues, Willie Mays encouraged him to never be intimidated by pitchers. “Get mean when you go to bat,” advised Mays. “And if they try to knock you down, act like it doesn’t bother you. Get back up there and hit the ball. Show them.”25 Clemente made good use of this advice during a game at Dodger Stadium on June 4, 1967. After Clemente hit a home run in the fifth inning, Don Drysdale threw a “duster” at him in his next at-bat, sending him to the ground.26 With the count 3-and-1, Clemente drove the next pitch an estimated 430 feet over the center-field wall. For his efforts, Clemente was greeted with a loud round of applause by the Dodgers faithful as he rounded the bases.27

Clemente’s power production was so consistent that offnights at the plate attracted attention. In the All-Star Game in Anaheim on July 12, 1967, he struck out four times for only the second time in his career. Clemente’s National League teammates were shocked by what they saw, prompting Atlanta Braves catcher Joe Torre to deadpan, “Did everybody take notes on how to pitch to Clemente?”28

Perhaps one of the most overlooked of Clemente’s home runs came in the second game of a doubleheader on June 27, 1971, at Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia. He belted a pinch-hit homer off Joe Hoerner to become the first of only seven players to hit a home run to Veterans Stadium’s upper decks in its 33-year history.29 Clemente’s feat was underappreciated at the time because of a newspaper strike in Pittsburgh but has since been validated by multiple witnesses, including the Phillies players.30

On September 30, 1972, Clemente became only the 11th player to reach 3,000 career hits. His landmark hit came at home off the Mets’ Jon Matlack, a leadoff double in the fourth inning. Clemente dedicated the hit to Pirates fans, the people of Puerto Rico, and Roberto Marin, the Puerto Rican businessman who originally invited Clemente to play on his softball team and became so impressed with his performance that he recommended that the Brooklyn Dodgers sign Clemente.31

CLEMENTE’S APPROACH TO HITTING

Through the years baseball fans and historians have offered several possible reasons for why Clemente, a perennial challenger for the National League batting title, rarely set home-run records. Clemente, for his part, claimed it was due to the deep dimensions of Forbes Field: 365 feet in left field, 406 feet to left-center field, 457 feet to deep center field. “I would hit more homers if I were playing anywhere but in Pittsburgh,” he said. “Forbes Field is the toughest park to hit home runs. If I played in Wrigley Field, I’d be a power hitter. I could hit 35 to 40 homers a year with my home games there.”32 Said longtime teammate Bill Mazeroski, “Don’t let anybody kid you he can’t hit for distance. When he wants to, he can power one as far as anybody in baseball. He’s smart enough to go for line drives at Forbes Field. That’s no park for home run hitters.”33

Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh offered his own rationale for Clemente’s offensive results. “I have always said that everybody expects too much of Roberto. He’s batting in the third position and in my style of play his job is to set up runners as well as drive them in. If you were to take Roberto’s runs set up, you’ll come up with a tremendous plus in his favor. Everybody always mentions the RBIs, but nobody ever mentions the runs set up. That’s equally important.”34

A potential clue to the origin of Clemente’s raw offensive power likely lies in the mechanics of his swing. According to Clemente biographer Bill Christine, “No kid on a sandlot will ever be taught to swing a bat like Roberto Clemente. The batter’s box was never deep enough for him. He had reflexes which enabled him to wait until the last fraction of a second before whipping the bat around. His hands, those strong hands and powerful wrists, he kept them close to the midsection. He felt that there was no pitch that was impossible for him to attack.”35

Generating power off his left foot, Clemente “would never swing the bat at the baseball, he would always throw the bat at the baseball.”36 His unique lunging motion meant that “Clemente made his charge at the pitchers like a mad man.”37 Interestingly, during his 1966 MVP season, Clemente’s offensive numbers rose to career highs in home runs and RBIs, which he attributed in part to improved field conditions at his home ballpark that helped him enhance his swing. “For years, I have been pleading with somebody in charge at Forbes Field to put clay instead of sand in the batter’s box,” he said. “Suddenly, this year, they put clay in the batter’s box. Now I have firm footing. Now I can get a toe-hold.”38

Regardless of how he did it, Clemente demonstrated incredible offensive ability to hit virtually any pitch for power to any part of the ballpark. As Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times noted, “They didn’t make the pitch Roberto Clemente couldn’t hit. All he required of a baseball was that it be in the park. He was the most destructive World Series player I ever saw outside of Ruth and Gehrig.”39

Born and raised in Newfoundland, MARK DAVIS developed a passion for baseball and the Toronto Blue Jays in his youth that continues to this day. A lifelong learner, he holds an undergraduate and master’s degrees in economics, as well as a PhD in public policy. Mark is a published academic author and a relatively new SABR member. He enjoys researching baseball history and has contributed three articles to the SABR book commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Toronto Blue Jays’ 1992 World Series championship. He currently resides in Ottawa with his wife, Melissa, and their young daughter, Felicity.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank David Speed and Bill Nowlin for their helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this article.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, Newspapers.com, and Clemente’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 Associated Press, “Pete Rose Given Clemente Award,” Wilmington (Ohio) News Journal, May 13, 1976: 16.

2 Associated Press, “Clemente Claims He’s Best in Game,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 21, 1964: 23.

3 Bruce Markusen, Roberto Clemente: The Great One (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, Inc., 2013), 22.

4 Markusen, 23.

5 Markusen, 26.

6 David Maraniss, Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 27.

7 Bill Christine, “Roberto! A Self-Made Hitter,” New York Daily News, April 3, 1973: 146.

8 Markusen, 29.

9 Stew Thornley, “Roberto Clemente’s Entry into Organized Baseball: Was He Hidden in Montreal?” Accessed April 7, 2022, https://milkeespress.com/clemente1954.html.

10 Lloyd McGowan, “Rookie Roberto’s homer, Lasorda Win, Revive Hopes,” Montreal Star, July 26, 1954: 28.

11 Markusen, 52.

12 Jimmy Cannon, “Clemente Still Wonders: Who’s Stranger in Field?,” Orlando Evening Star, March 21, 1972: 30.

13 Les Biederman, “Roberto’s Bat Softens Rivals for Buc Raids,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1966: 6.

14 Les Biederman, “The Scoreboard,” Pittsburgh Press, June 6, 1955: 22.

15 Jim Murray, “Roberto’s Revenge,” Los Angeles Times, July 1, 1964: 1.

16 Murray, “Roberto’s Revenge.”

17 Associated Press, “300-Win Hurlers History?” Rome (Georgia) News-Tribune, January 7, 1998: 3B.

18 Les Biederman, “Bailey in Fast Company,” Pittsburgh Press, June 14, 1963: 28.

19 Les Biederman, “Phils Blast Friend Early, Turn Back Pirates, 7 to 2,” Pittsburgh Press, May 12, 1957: 69.

20 Les Biederman, “Tape Measure Homer Belted by Clemente at Wrigley Field,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1959: 10.

21 Sandy Koufax with Ed Linn, Koufax (New York: Viking Press, 1966), 220.

22 Frank Finch, “Bucs’ Clemente Toughest NL Hitter,” Los Angeles Times, June 24, 1965: 50.

23 Les Biederman. “Clemente’s ‘Biggest’ Game Wasted,” Pittsburgh Press, May 16, 1967: 34.

24 Biederman. “Clemente’s ‘Biggest’ Game Wasted.”

25 Biederman. “Clemente’s ‘Biggest’ Game Wasted.”

26 Charley Feeney, “Veale Gets 7th Victory with Help,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 5, 1967: 34.

27 This Day in Baseball, “Roberto Clemente Hits 2 Home Runs off Don Drysdale,” Accessed April 22, 2022, https://thisdayinbaseball.com/roberto-clemente-hits-2-home-runs-off-don-drysdale-accounting-for-all-of-pittsburghs-runs-in-a-4-1-victory-over-los-angeles-clementes-first-bomb-travels-400-feet-to-tie-the-s/.

28 Les Biederman. “Reds’ Perez Lives Like a King, Plays Like One,” Pittsburgh Press, July 12, 1967: 62.

29 Gene Collier, “Of Veterans: One Spit On, the Other Knocked Down,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 26, 2003: B-2. This home run has often been misquoted as the “Liberty Bell Ringer” that hit the decorative Liberty Bell attached to the center-field upper deck at Veterans Stadium. Clemente researcher David Speed has noted that while the home run did not hit the bell, it was nonetheless an excellent example of Clemente’s raw offensive power.

30 David Speed Facebook post: June 27, 2018, Accessed April 30, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=10215342221376250.

31 Charley Feeney, “Roberto Collects 3000th Hit, Dedicates It to Pirate Fans,” The Sporting News, October 14, 1972: 15.

32 “Clemente Claims He’s Best in Game.”

33 Al Abrams, “Sidelights on Sports: Clemente Not Appreciated?,” Pittsburgh-Post Gazette, February 26, 1965, 20.

34 Associated Press, “Clemente Sparks Late Rally, Pirates Win, 6-5,” Monessen Valley Independent (Monessen, Pennsylvania), May 18, 1971: 9.

35 Bill Christine, “Roberto! A Self-Made Hitter.”

36 Markusen, 168.

37 Les Biederman, “Clemente Sinks Feet in Clay to Mold Stout Swat Figures,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1966: 8.

38 Biederman, “Clemente Sinks Feet in Clay to Mold Stout Swat Figures.”

39 Jim Murray, “Clemente: You Had to See Him to Disbelieve Him,” Los Angeles Times, January 3, 1973: 49.