American Indian Baseball in Old North County: San Diego Heritage at Riverside’s Sherman Institute

This article was written by Tom Willman

This article was published in The National Pastime: Pacific Ghosts (San Diego, 2019)

Sherman Institute, the new federal Indian boarding school at Riverside, California, as it appeared in the popular national Leslie’s Weekly in 1902. (COURTESY OF TOM WILLMAN)

On May 3, 1905, much of California discovered that Native Americans really could play baseball.

On that day the team from Sherman Institute, the three-year-old federal Indian boarding school in Riverside, played its first game against college competition. The result was startling: In 10 innings, playing in Los Angeles, Sherman beat USC, 7–4.

“Back East somewhere,” the Los Angeles Times noted, “some scribe once said the Indians were a success as fielders, but could not bat. He was half right.” As for the condescension that Indians couldn’t really be expected to understand the inside game, the Times writer observed: “‘Poor Lo’ has been the subject of much misplaced sympathy.”1

The game seems to have gone unremarked in San Diego, which was too bad. In a real sense, it was a San Diego County story. Among those on the field for Sherman that spring day in 1905 were baseball coach (and star athlete) Joe Scholder, a Kumeyaay-Diegueño Indian from Mesa Grande, east of Escondido; left fielder Camillo Ardillo, from the relocated Cupeño home at Pala, east of Fallbrook; second baseman Sylvas Lubo, who drove in the first run against USC; Freddy Casero, who put on an acrobatic show at short, was, like Lubo, from the Cahuilla reservation, northeast of Pala; catcher Alex Tortes, who had three hits that day; and right-fielder Ignacio Guanche, who hit one out of the park in the fifth and drove in another run in the 10th to break USC’s heart. Tortes and Guanche were both from the Santa Rosa reservation of Mountain Cahuilla.2

These reservations are strung like a necklace around the 6,000-foot landmark of Palomar Mountain in North County San Diego. They are one cluster among several dozen reservations and tribal lands sprinkled through the rugged chaparral backcountry of San Diego and Riverside counties. These are the tribes that formed Sherman Institute’s original core population. When Sherman, new and untested, beat USC in 1905, it was a heady win. The victory helped mark Sherman as a showcase for Indian athletics.

The first three decades of the 20th century are generally viewed as the great age of the Native American athlete.3 Much of that reputation rests on the well-publicized achievements of federal Indian boarding school athletes against top competition in the East and Midwest. Chief Bender and Jim Thorpe, both products of Carlisle Institute in Pennsylvania, are leading baseball examples. Sherman Institute, 25th and last in the chain of these Indian schools, provided similar exposure for top American Indian athletes of the West. It also provided a window on how ardently baseball was embraced across this “Mission Indian” country.

Until 1893, when Riverside County was created, all of this region was in San Diego County. The foundations of tradition were anchored here: the tribal homelands, the missions at San Diego and San Luis Rey (Oceanside), the asistencia (sub-mission) at Pala, and the fiefdoms of the land-grant ranchos.4 But Sherman Institute, though farther north in Riverside, had a special claim to this North County heritage. The wife of Sherman’s chief clerk, known simply as Mrs. Mitchell, lived quietly on campus, sometimes serving as matron in the girls’ dormitory or cook in the dining hall.5 It was a humble life of service for the former Estella Erolinda Estudillo. The landmark Estudillo Adobe in Old Town San Diego State Historic Park and the sprawling 35,500-acre Rancho San Jacinto Viejo were some of her family’s lands.6 Her brother, a frequent guest at Sherman, was Miguel Estudillo, Riverside‘s influential former state senator and longtime city attorney.7 This notable San Diego association would serve Sherman Institute well for 38 years.8

That shared heritage was soon enhanced as Sherman and mighty Carlisle forged an unofficial bicoastal athletic circuit. There was a regular two-way flow of North County Indian students between the schools. Joe Scholder left his North County home to play football at Carlisle, then returned to coach at Sherman. Soon he was joined by the great Bemus Pierce (Seneca), who had been his Carlisle football captain. Both men would train generations of Sherman athletes before retiring in the 1940s. Meanwhile, over the years at least 75 Mission Indian students like Scholder would appear on the rolls at Carlisle.9 More than a few were athletes.

Soon Sherman would earn its own national reputation in football and distance running. But it was baseball that would be Sherman’s sport of greatest and most lasting importance. Baseball had been played in San Diego since the spring of 1871.10 By the 1890s, the game was being played on North County reservations.11 Some of these players would be with Sherman on May 20, 1905, when they met a touring team from Japan’s Waseda University. The matchup drew a large crowd to Fiesta Park in Los Angeles.12 Waseda won 12–5, but several of its runs were unearned, and Sherman had the bases loaded when the game ended.13 It had not been a mismatch. And it would pay a remarkable dividend. In September 1921, a team of former Sherman players sailed to Japan by special invitation to play a series of exhibition games with Japanese universities. Sherman baseball had been elevated to an instrument for diplomacy.14

As Sherman expanded its student population, a winning tradition was created. By the spring of 1907, Sherman was educating students from 48 distinct tribes.15 The player pool deepened. There also were intramural squads representing the vocational shops, faculty-student games, and an alumni-student game at commencement festivities. At Sherman, baseball became a key part of the pan-Indian educational experience.

Baseball appealed to Native Americans on another level as well. The tribes and bands of San Diego and Riverside counties had their own history of abuse by the dominant culture. Broken treaties, usurped lands, lost water rights: All the familiar elements are part of this region’s history. Reformer Helen Hunt Jackson’s writings and popular 1884 novel Ramona, framing the Indians’ plight, were researched and set in this landscape.16 As recently as 1903, the Cupeño Indians of San Diego County had been forced from their traditional home at Warner’s Hot Springs and compelled to relocate to Pala.17 Yet life, and baseball, went on. Barely a year later, in the spring of 1904, the Pala Indian baseball team traveled to the coast to play Oceanside. Oceanside won, 14–13. “Both teams put up a good article of ball and the game was closely contested throughout,” the San Diego Evening Tribune reported, adding of Pala rooters: “There was a large crowd present from San Luis Rey and the surrounding country.”18 Native Americans played baseball for fun; they turned out for excitement, for holiday diversion, even through complicated times. Certainly at Sherman, they also played for the fierce joy of showing people what they could do when the field was level. In the clash of cultures, baseball could be everyone’s national pastime.19

Sherman’s influence as a sustaining supporter and promoter of Native American baseball is clear. It’s harder to imagine the spread of baseball as a popular recreation through a rural countryside, especially among insular reservations. But we get a glimpse of the dynamic through the testimony of the best-known Cahuilla player, Chief Meyers.

Sherman’s influence as a sustaining supporter and promoter of Native American baseball is clear. It’s harder to imagine the spread of baseball as a popular recreation through a rural countryside, especially among insular reservations. But we get a glimpse of the dynamic through the testimony of the best-known Cahuilla player, Chief Meyers.

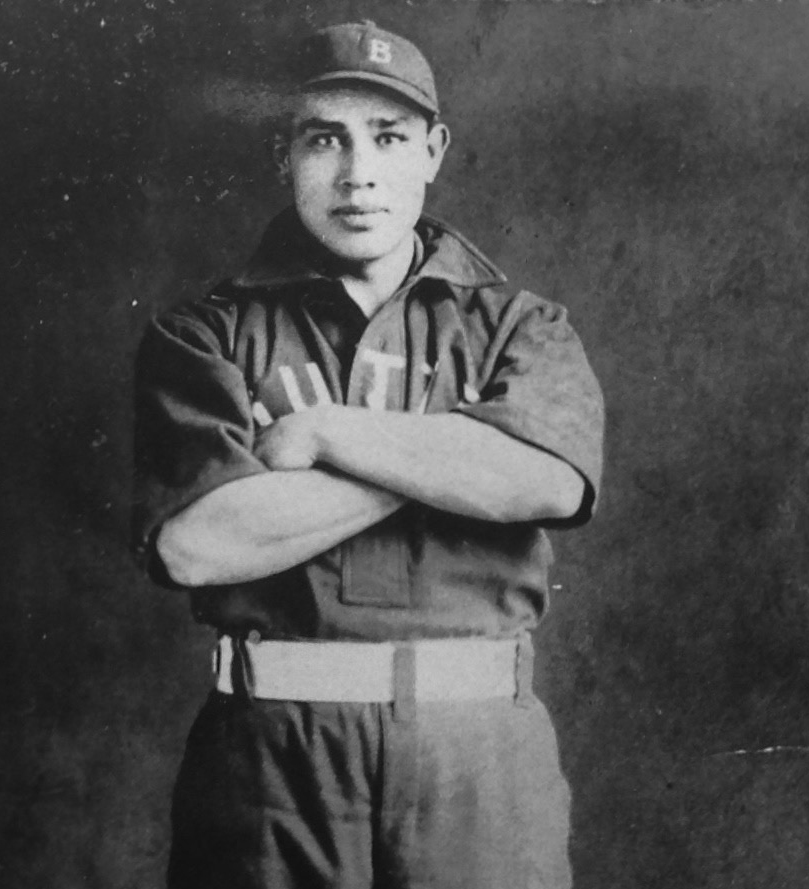

John Tortes Meyers was born in Riverside in 1880. His father was a Civil War veteran who died when Meyers was small. Meyers’s mother was Cahuilla, and much of his youth was passed among her people. He spent some time in a small village called Spring Rancheria, near Mount Rubidoux and the fast-growing Riverside downtown. He also knew the traditional home of the Mountain Cahuilla, the Santa Rosa tribal lands on the flank of Mount San Jacinto, 60 miles to the east.

He was raised in a home where education was important — his mother was multilingual, his sister became a nurse — but this was before child labor laws. Meyers did not finish public school. Instead, he went to work in Riverside’s groves and arbors, contributing to the family welfare. He would set out for the dusty mining leagues of Arizona and points east to seek his baseball fortune. Along the way he would spend a year at Dartmouth University, an association he prized all his life. But he would be going on 29 before he played in the majors, and it was those years spent living for the love of the game that would make him one of the National League’s best hitters.

After the World Series of 1911, Meyers came home to Riverside. A local reporter caught him in a nostalgic moment, and Meyers recalled being a kid and admiring the team of G.D. Allen, who ran a sporting goods store in town. “He is the old original 33d degree fan,” Meyers said, “and when I was a mere kid years ago, I used to watch his team play and long for the time to come when I would be big enough to play on it. The team was disbanded before I reached that age, but Mr. Allen has still retained his interest in baseball.”20

In 1913, the Chicago White Sox came to Riverside for a spring training game against Sherman. The giddy crowd, estimated at 3,000, packed Evans Park to see Ed Walsh, Ray Schalk, Buck Weaver, Harry Lord, and Shano Collins. To the crowd’s delight, the Sox turned it into a fun exhibition.21 Final score: Chicago 14, Sherman 3.22 But Sherman had its moments. Alum Saturnino Calac (Luiseño, Rincon band) was chosen Sherman’s player of the game. He was busy and errorless at shortstop and blasted an exciting triple. Calac would go on to play Class D ball in California’s State League and would return to coach at Sherman, where a regular parade of Calac clan athletes would enroll.

Members of the 1914 Sherman Institute baseball team pose on the school lawn. The tall player at center holding the tip of the Sherman pennant is Emil Benson, Sherman’s star pitcher that year. Benson threw a no-hitter against the University of Redlands. (CUMBERLAND COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

On March 14, 1914, Sherman defeated the University of Redlands, 3–1. Sherman’s Emil Benson had 13 strikeouts and a no-hitter with no earned runs, according to Riverside coverage.23 It was a symbolic triumph for Benson. On Sherman’s rolls, his tribe was listed as “Digger.”24 This common demeaning term was an echo from the Gold Rush; it suggested lives of low subsistence, and it had justified generations of abuse, particularly against Central Californian Native Americans.25 Benson (Mono) was from that country. But at Sherman, he also had the signature interests of a gifted student. That year he was involved in Sherman’s Chautauqua-like literary societies, he was the editor of the Sherman Bulletin, and he would be the only boy in Sherman’s small academic graduating class of 1914.26 He was pitching for Riverside Poly High School in the spring of 1917 when America went to war. He dropped out to enlist in the Army.27 He would pitch for the best teams at Camp Kearny, the sprawling “temporary camp” that popped up on the flats north of San Diego, before going overseas. Emil Benson would return as a sergeant and take up a long career as an Indian educator.

In those years, many former Sherman players found ways to go on living baseball lives. Lou Lockart (Pomo, Sherwood Valley Rancheria) had enrolled at Sherman in 1906. He had a hot fastball and a roundhouse curve and he quickly became Sherman’s main pitcher. After two good years at Sherman, he bobbed up in many places. In 1910 he pitched for the Nebraska Indians. In 1911, he was at spring training in Murrieta with the Pacific Coast League Los Angeles Angels. He pitched decently in two games but was let go. Two months later he was reportedly pitching for an “all Japanese” touring team.28 The winter of 1912 found him pitching for the Los Angeles Trainmen in the Beach League.29 In 1918, rediscovered, he went to spring training with the Oakland Oaks of the PCL. In the third inning of an intersquad game he snapped a ligament in his pitching arm, ending his career.30

That same spring of 1918, a young pitcher named Chief Jamison was in camp with the Angels.31 Bert Jamison (Seneca) had been a multisport athlete at Haskell, the Kansas Indian school, and there had met his wife, Sherman graduate Mary Golsh (Mission, Valley Center). In the Angels’ camp, Jamison was wild, but his speed encouraged patience. Jamison was still with the Angels when the team discovered that Detroit Tigers great Sam Crawford was done with the majors and available. The Angels scooped Crawford up and Jamison was the last man cut when the squad broke camp.32 Jamison would become a respected Sherman coach through the 1920s.33

Of course, in 1918 everything changed. The civilian populace was drawn into the daily sacrifice of the war effort. Baseball seasons were cut short. Casualty counts mounted horrifically. On May 29, 1919, the Sherman Bulletin published a memorial page for nine former students who had died in France. One was Albert Ray, an Olympic-class runner. Three others had been ballplayers: Thomas Tucker, Alfonso Calac, and Phillip Calac. Among the many who served, another name is memorable in this context. Chief Meyers joined the U.S. Marine Corps in the war’s waning days. He did not see fighting. Meyers died in 1971. His grave marker bears no mention of baseball, only of his USMC service. He lies buried just upriver from the site of Spring Rancheria.34

Soon enough, Sherman would be overtaken by another game changer. As new high schools and colleges began to field teams, join leagues, and regulate competition, Sherman was odd-man-out when schedules were built. Under governance of the nascent California Interscholastic Federation Southern Section, Sherman would be stuck in freelance competition until 1939.35

And yet: Today, after a century of evolution, Sherman — now fully accredited Sherman Indian High School — still exists as a Native American boarding school. It still occupies the same land where its cornerstone was laid in 1901. Its athletes still compete with high success, and on grounds that date to the Deadball Era its baseball teams still play with old-school panache. Sherman Indian High School stands as a living monument to the great age of the Native American athlete, and North County San Diego has had a lot to do with that.

TOM WILLMAN is a retired newspaper writer. Previous articles have appeared in “Northern California Baseball History,” for SABR’s 1998 annual convention, and in “The National Pastime” in 2011 on baseball in Southern California.

Acknowledgments

Much of the research for this project, including a survey of bound volumes of the weekly Sherman Bulletin from 1907 to 1920, was done at the Sherman Indian Museum at Sherman Indian High School in Riverside, California. I wish to acknowledge the long-running hospitality, insightful guidance and assistance of the museum’s curator, Lorene Sisquoc. The museum invites research inquiries. For more information, see http://www.shermanindian.org/museum/

A growing archive of Sherman images and documents is now available on the web, through a partnership with the Library of the University of California, Riverside. Visit Calisphere.org and find Sherman at “View All Statewide Partners.”

I also wish to thank Ruth McCormick, local history specialist at the main Riverside Public Library, for her resourceful help and patience, and for sharing her passion for baseball history as well. For information about the Riverside Local History Resource Center, see https://www.riversideca.gov/library/history.asp

The Cumberland County (Pennsylvania) Historical Society is keeper of the rich online historical archive of Carlisle Indian School, including digital images, student publications, records and manuscripts. For more about their research opportunities, see https://carlisleindian.historicalsociety.com

Notes

1 “Indians Play Baseball Too,” Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1905.

2 Sherman Institute student registration log books, Sherman Indian Museum, Riverside, California.

3 Joseph B. Oxendine, American Indian Sports Heritage (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Books, 1988), 239.

4 Richard L. Carrico, Strangers in a Stolen Land: Indians of San Diego County From Prehistory to the New Deal (San Diego: Sunbelt Publications, 2008), 135 et seq.

5 “Staff Changes at Sherman Institute Made Known,” Riverside Daily Press, July 31, 1940.

6 “La Casa de Estudillo,” California Department of Parks and Recreation, https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=28012.

7 Elmer Wallace Holmes, History of Riverside County California; with Biographical Sketches; Hon. Miguel Estudillo (Los Angeles: Historic Record Company, 1912) 344–8.

8 Riverside Enterprise, November 8, 1919; “Staff Changes at Sherman Institute Made Known,” Riverside Daily Press, July 31, 1940.

9 “Carlisle Indian School History: Mission,” Cumberland County Historical Society, https://carlisleindian.historicalsociety.com/mission/.

10 Bill Swank, The San Diego Historical Society, Baseball in San Diego: From the Plaza to the Padres (San Francisco: Arcadia Publishing, 2005), 11.

11 Swank, 126.

12 “A New Departure: An Epoch-Marking Game of Base Ball,” Sporting Life, June 10, 1905.

13 “Wiry Japs Wallop Reds,” Los Angeles Times, May 21, 1905.

14 “Sherman Team Goes to Japan to Play Ball,” Arlington Times, September 16, 1921.

15 “General News,” Sherman Bulletin, March 6, 1907.

16 Clifford E. Trafzer, Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, and Lorene Sisquoc, eds. The Indian School on Magnolia Avenue: Voices and Images From Sherman Institute (Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 2012) 45–7.

17 Carrico, Strangers in a Stolen Land, 155.

18 San Diego Evening Tribune, May 23, 1904.

19 John Bloom, To Show What an Indian Can Do: Sports at Native American Boarding Schools, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000) XVI–XX; Trafzer, Gilbert, and Sisquoc, eds., The Indian School on Magnolia Avenue 6, 27–8.

20 “Meyers is Home After Big Games,” Riverside Daily Press, November 6, 1911.

21 “White Sox Defeat Redskins, 14 to 3,” Chicago Inter Ocean, March 26, 1913.

22 “Play Y.M.C.A. Benefit Ball Game: The Largest Crowd In The History Of Riverside’s Big Ball Park See The Chicago White Sox Defeat Sherman,” Sherman Bulletin, March 26, 1913.

23 “Riverside Wins in Three Games,” Riverside Daily Press, March 16, 1914.

24 Sherman Institute student registration logbooks: Emil Benson, original enrollment October 19, 1911.

25 Allan Lönnberg, “The Digger Indian Stereotype in California,” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 3, No. 2, UC Merced, 1981. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6qq09790.

26 “Graduating Class of Sherman Institute,” Riverside Daily Press, March 15, 1914.

27 Emil Benson World War I service dates, in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850–2010, (Provo, Utah). Accessed at ancestry.com.

28 “Japanese Baseball Star Proves to be an Indian,” Los Angeles Times, May 11, 1911.

29 “School Sports,” Sherman Bulletin, November 13, 1912.

30 “At the Training Camps,” Los Angeles Times, March 16, 1918.

31 “At the Training Camps.”

32 “Tigers Brace Up and Win,” Los Angeles Times, March 29, 1918.

33 “Sherman Indians Play Ring Around the Rosy with Yuma Braves: Roll Up a Score of 75 Points in Championship Grid Battle,” Riverside Daily Press, January 2, 1923.

34 Chief Meyers is buried at Green Acres Memorial Park in Bloomington, California.

35 Dr. John S. Dahlen, “Sherman Indian High School,” CIF Southern Section, https://cifss.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/CIFSS-History-31-Sherman-Indian-School.pdf.