Analyzing Jackie Robinson as a Second Baseman

This article was written by Mike Huber

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

Second base. It might not have the pizzazz of shortstop. It also might not have the glamour of third base, which is known as the “hot corner.” Fans don’t normally expect the same power numbers from a second baseman that they see in others who play the infield, like the stereotypical slugger who plays first base. And yet second base is called the keystone position.

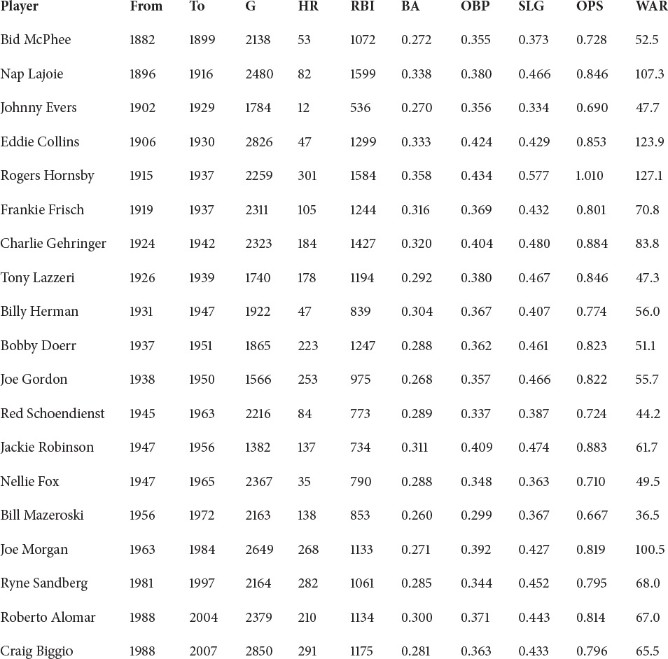

Over the past century many second sackers have put up great offensive numbers. Twenty second basemen are enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.1 In an attempt to determine the greatest-ever offensive force from a second baseman, let’s list these Hall of Famers in approximately the chronological order in which they appeared in the major leagues. They all have played second base for most, if not all, of their careers. With the exception of Jackie Robinson, who was not permitted to play in the big leagues until he was 28 years old, and Joe Gordon, who missed two seasons during World War II, all the players listed had relatively long careers.2

(Click image to enlarge)

From this chart we can see that Robinson did indeed have the fewest number of games played. While Rogers Hornsby might be acknowledged as the greatest offensive second baseman to play the game, given that his Wins Above Replacement (WAR) value is higher than the others, we should recognize that it is difficult to compare players from different eras, especially given that some did not play in all of their potentially prime years.

That leads to the question: Who was the greatest second baseman of the late 1940s to mid-1950s, when Jackie Robinson played?

Jack Roosevelt Robinson debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, and he was immediately an everyday player. An everyday player who played first base. What?!?

Robinson had played second base for the Kansas City Monarchs as part of the Negro Leagues. In 1945, he batted .414 for the Monarchs. Signed by Branch Rickey, Robinson joined the Montreal Royals, the top farm team in the Brooklyn organization, in 1946. That season he led the International League by batting .349 and stealing 40 bases, all the while playing second base. When Robinson was called up to the Dodgers, he did not disappoint, leading the National League in 1947 with 29 stolen bases while posting a solid .297 batting average. The Brooklyn first baseman earned Rookie of the Year honors, winning the award over New York Giants pitcher Larry Jansen and Yankees hurler Spec Shea.

The 1946 Dodgers had featured a solid leadoff batter in Eddie Stanky. The 31-year-old Stanky led the National League in both 1945 and 1946 in walks, with 148 and 137, respectively. Combined with his .273 batting average in 1946, he had the knack of getting aboard and scoring runs. His on-base percentage was tops in the league that year (.436), so manager Burt Shotton penciled in Stanky to lead of in 1947 as well, in order for him to get on base and be moved along by the strong-hitting Robinson and perhaps driven in by Bruce Edwards, Carl Furillo, or Dixie Walker, all of whom had at least 80 RBIs in that season.

Since Stanky was a fixture at second base, Robinson played first. However, in 1948, Stanky was dealt to the Boston Braves during spring training. This meant that Robinson slid over to second base for the 1948 campaign, and over the course of his next nine seasons, Robinson played 748 games (starting 740 of them) at second base. More on this later.

Jackie Robinson, of course, was the first Black ballplayer to play major-league baseball in the twentieth century. No one knows what numbers Robinson would have put up had he been allowed to begin playing baseball at the age of 21 or so, like so many of the others now enshrined in Cooperstown. More than likely, though, his professional baseball career would have been affected by the war.

From our table above, we see that Robinson is one of five Hall of Fame second basemen who played during the mid-1940s to mid-1950s. Let’s trim the table to focus on Robinson’s playing era.

Using the WAR statistic, which is a nonstandardized measure that attempts to indicate how many more wins a player would provide for his team in lieu of a replacement player, we can compare the best players who played second base during Robinson’s time in the majors.

While there is no clear-cut or consistent formula to compute the WAR number, there is some sense of uniformity. Some websites calculate the statistic differently. Using baseball-reference.com/leaders, second baseman Rogers Hornsby ranks 12th in the all-time list with a WAR of 127.1. To put this number in perspective, the leader in this category is Babe Ruth with a WAR of 182.5. Robinson’s career WAR value (61.7) ranks 169th all-time.

Back to our era, which took place after World War II. How do Jackie Robinson, Bobby Doerr, Joe Gordon, Red Schoendienst, and Nellie Fox stack up against one another? Can we go beyond using WAR for comparison? For the sake of comparison, Billy Herman is not included, since he ended his career the season before Robinson started at second base. Likewise, Bill Mazeroski is not included, as he was a rookie in Robinson’s final playing season.

According to baseball-reference.com/leaders/WAR_career.shtml, WAR has a scale for a single season: 8+ indicates MVP quality, 5+ indicates All-Star quality, 2+ indicates a starter, and 0-2 indicates a reserve. Any number less than 0 indicates a replacement player. Further, WAR can be calculated as a total player number (offense and defense) or separately for offense and defense.

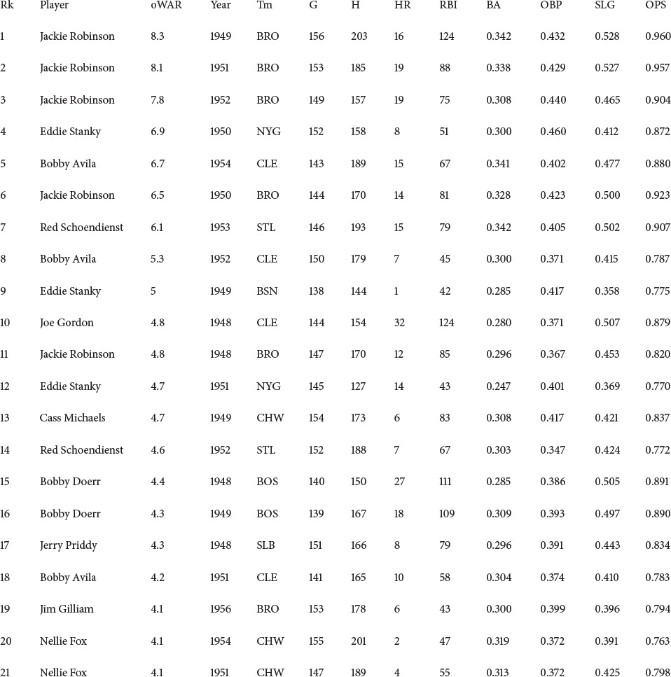

If we search for all second basemen3 who played from 1948 through 1956 who had an Offensive WAR (oWAR) of at least 4.0 (not quite All-Star quality), we obtain the following table (bold entries designate league leaders):

(Click image to enlarge)

Robinson is clearly the offensive leader. He put up six consecutive seasons in the top 10 list in oWAR during his career, from 1948 through 1953 (although he played only nine games at second base in 1953), and five of those times put him into the top 11 spots during this period. His 1952 oWAR mark of 7.8 led all major leaguers, not just second basemen, but as can be seen, it was only his third-best seasonal performance. He owns the top three spots in this table for all second basemen with his 1949, 1951, and 1952 performance, and he has four of the top five oWAR numbers. This also confirms Baseball-Reference’s ratings, as Robinson was the 1949 National League Most Valuable Player.

In his 1949 MVP season, Robinson led all National League batters with a .342 batting average. His 37 stolen bases led every player in the majors (as did the 16 times he was caught stealing).4 He had 17 sacrifice hits to pace the NL. His on-base percentage in 1952 (.440) was tops in the majors, justifying his replacement of Stanky in the lineup. By 1952, Robinson was batting in either the third or fourth position in the batting order. Robinson had six seasons in the top 10 in the National League Adjusted Batting Wins (consecutively, from 1949 to 1954). In three of those seasons, he placed in the top 10 of all major leaguers (1949, 1951, and 1952). Recall that Adjusted Batting Wins refers to a “set of formulas developed by Gary Gillette, Pete Palmer, and others that estimates a player’s total contributions to a team’s wins with his bat.”5 A value of 0 is an average performance, less than 0 is worse than average, and greater than 0 is better than average.

We see that many of the top-21 players in oWAR in the table above are indeed Hall of Famers, but none reached Robinson’s level.

DEFENSE

Robinson was a definite force with a bat, and once he got on base, he was a threat to score. What about his defense? Throughout baseball history, two qualities seem to have defined excellence at second-base defense: avoidance of errors and participation in double plays. Robinson’s plaque in Cooperstown claims that he “led second basemen in double plays four times.”6 However, some of the more recent measures seem to converge to a single point of agreement: The number of assists per game by a second baseman is of utmost importance in determining fielding skill. These numbers can be inflated in light of such matters as the first baseman’s range and the propensity of the pitching staff to induce groundballs.

In comparing offensive statistics of all second basemen in both the American League and National League from 1948 through 1956, we make some discoveries. First, Robinson did not start playing second base for the Dodgers until his second season (1948), when he played 116 games at second and 30 games back at first. (He also played six games at third base.) He then played all of his games from 1949 through 1952 at the keystone position (596 games). In 1953 the 34-year-old added the outfield to his repertoire (76 total games). In fact, after 1952, Jackie played only 36 games at second (in five seasons). As a result, in 10 seasons in the National League, Robinson played 748 games (with 740 starts) at second, which comes to 55.24 percent. Amazingly, he started in all but 10 of his 1,354 total games over that 10-season stretch.

Robinson was a six-time All-Star, and he received votes for the league’s Most Valuable Player award in all but two seasons, claiming the honor in 1949. In 1953 he was voted in as a reserve All-Star outfielder and appeared as a pinch-hitter. The next season, he was the starting left fielder in the senior circuit’s lineup.

By comparison, Joe Gordon played all but two games in his career at second. He won the AL MVP Award in 1942 and was a nine-time All-Star. Bobby Doerr played all of his games at second and was a nine-time All-Star. Nellie Fox played all but eight games in his career at second. (And those eight were in his final season.) He won the AL MVP award in 1959 and was a 15-time All-Star (including twice each season from 1959 to 1961). Red Schoendienst played 1,834 games at second (89.7 percent of his total games) and was a 10-time All-Star.

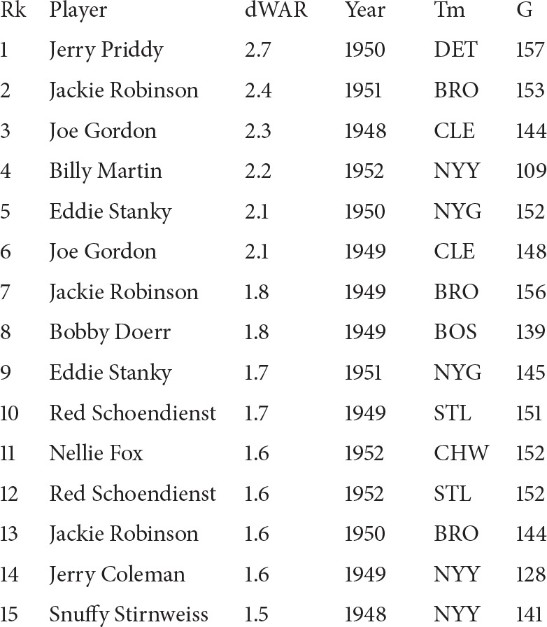

What to do? How do we normalize the data for equal comparisons? The table below provides a Defensive WAR value for second basemen between 1948 and 1952 (bold entries designate league leaders).

From 1949 to 1952, there were 15 instances in which a second baseman had a Defensive Wins Above Replacement (dWAR) value of at least 1.5. (Robinson also comes in at 16th with a 1.4 mark in 1952.) Baseball-Reference concedes that the “replacement level on defense is the league average.”7

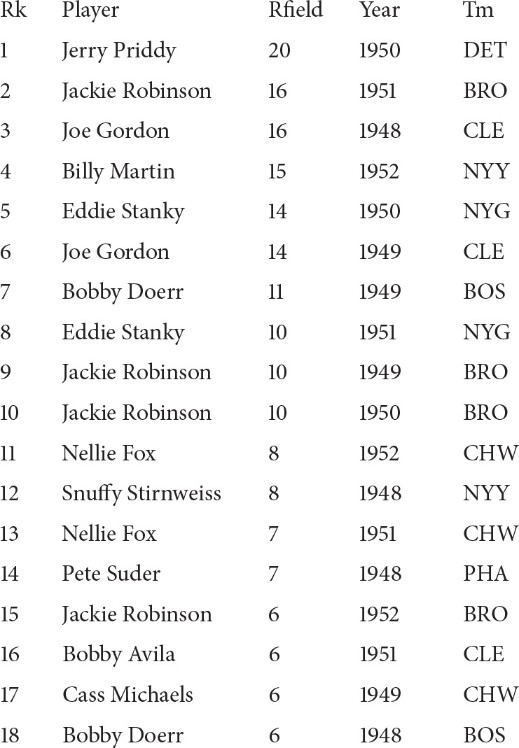

Robinson had a .983 fielding percentage in 748 games at second base, making 68 total errors but turning 607 double plays. There is a statistic known as WAR Fielding Runs (Rfield). The following table lists seasons for second basemen when an Rfield value of at least 6 was attained.

Fielding runs (Rfield) above average are relative to the positional average. Therefore, a +10 second baseman is 10 runs better than the average second baseman. The best during Robinson’s four seasons at second belongs to Detroit Tigers second baseman Jerry Priddy, with a value of +20 in 1950. But that was only one season. Only 18 times did a player score above 5, and Robinson had four of them (including the second-highest mark of 16 in 1951).

In 1951 Robinson led the National League in putouts (390) and assists (435) by a second baseman. Three times (1948, 1950, and 1951) he led all second basemen in fielding percentage.

Final note: A useful statistic in comparing the fielding of position players is the Total Zone Fielding Runs, which characterizes the number of runs above or below average the player was worth based on the number of plays made. Unfortunately, this statistic is available for second baseman only after 1953, the season when Robinson stopped his second-base duties.

It is safe to say that Robinson was the best second baseman in the majors, both offensively and defensively, during his playing days at the keystone position. His manager moved Robinson around the diamond and into the outfield, probably because he was a great athlete, but one thing is certain: Jackie Robinson deserved to be enshrined into the Hall of Fame based on his statistics.

MIKE HUBER is professor of mathematics at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Part of his research involves studying rare events in baseball, to include games in which a batter hits for the cycle. Mike joined SABR in 1996, and he enjoys writing for SABR’s Games Project. One of his first articles on hitting for the cycle for the Games Project described Jackie Robinson’s reverse natural cycle against the Cardinals, and that article is included in this book. Since then, he has chronicled more than 120 games involving the rare cycle.

Notes

1 The website at the Hall of Fame claims that 21 second basemen have been enshrined, but they show only 20 when directed to the page of second basemen.

2 Our list does not include Frank Grant, who played for the Cuban Giants, and, according to the Baseball Hall of Fame, was “perhaps the best of the African-American players who played in organized baseball in the 1880s, before the color line was drawn.” See baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/grant-frank.

3 The search restricts players who played at least 50 percent of their games in that season at second base.

4 Interestingly, Robinson stole 88 bases in his first three seasons but was caught 41 times. Over his next seven seasons, he stole 109 bases but was caught just 35 times.

5 See baseball-reference.com/leaders/abWins_top_ten.shtml.