Anheuser-Busch Buys the St. Louis Cardinals

This article was written by Russell Lake

This article was published in Sportsman’s Park essays

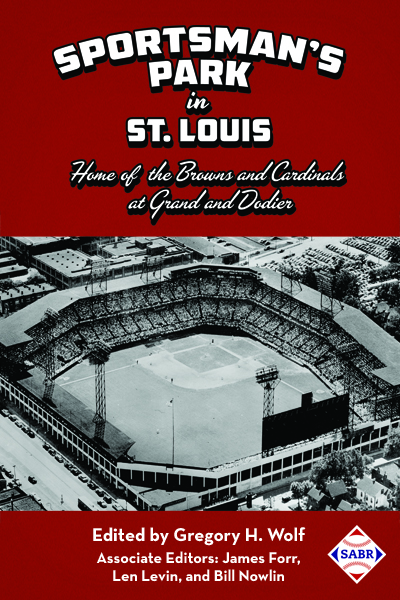

The players on the train carrying the St. Louis Cardinals back to Union Station should have been vibrant and fun-loving as it rolled through the Land of Lincoln on October 2, 1949. The Redbirds had thumped the Chicago Cubs, 13-5, at Wrigley Field in the season finale that afternoon. Thanks to a thrilling pennant race, the 1949 Cardinals set a home attendance mark of 1,430,676 at Sportsman’s Park, but they came up short again and suffered their third straight second-place finish in the National League. They lost by a single game to the Brooklyn Dodgers after dropping six of their last nine games. Most of the players sat in the private parlor car with their eyes closed thinking about lost chances over the prior 10 days.

The players on the train carrying the St. Louis Cardinals back to Union Station should have been vibrant and fun-loving as it rolled through the Land of Lincoln on October 2, 1949. The Redbirds had thumped the Chicago Cubs, 13-5, at Wrigley Field in the season finale that afternoon. Thanks to a thrilling pennant race, the 1949 Cardinals set a home attendance mark of 1,430,676 at Sportsman’s Park, but they came up short again and suffered their third straight second-place finish in the National League. They lost by a single game to the Brooklyn Dodgers after dropping six of their last nine games. Most of the players sat in the private parlor car with their eyes closed thinking about lost chances over the prior 10 days.

Manager Eddie Dyer talked softly with his wife in a closed compartment, and wondered how long it might be before his team would get this close again.1 Farther down the tracks, their landlord, the St. Louis Browns, wrapped up a dismal season of their own by losing 101 games while drawing fewer than 271,000 spectators. Although the two franchises paired to win five pennants and three world championships in the 1940s, those seasons of glory seemed far behind in the rearview mirror when the calendar turned to a new decade.

The 1950 Cardinals finished fifth and fell into the second division for the first time since 1938, while the Browns maintained their losing ways in both games and attendance. The Browns seemed to graciously shrug at the “laughing stock” slogan attached to them – “First in shoes, first in booze, and last in the American League.”2 As different managers came and went for both Mound City squads during the next couple of seasons, a war of nerves between the two team presidents also broke out and festered. In the most noteworthy squabbles, new Browns owner Bill Veeck demanded that the Cardinals’ Fred Saigh sign a new ballpark lease, and Veeck snatched up Cardinals pitcher Harry “The Cat” Brecheen for double the salary Saigh was paying him. Saigh later claimed that the Browns had tampered with Brecheen before the Cardinals released the veteran southpaw at the end of the 1952 season.3

In actuality, the maverick mannerisms of Veeck, along with his multiple Barnum & Bailey promotion tactics seeking to woo area fans to the Brownies, were the least of Saigh’s worries. Saigh had been indicted by a grand jury earlier in the year for federal income-tax evasion, and despite proclaiming his innocence of the charges in an article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, had to consider selling the Cardinals. “The Cardinals are a great ballclub and I would not want them to be hurt in any way even though I believe that I will be completely vindicated,” Saigh said. “I don’t have this coming to me. I’m completely shocked because I understood that a settlement was being made. I’d better say no more until I see my lawyer.”4

The citizens of St. Louis and its metropolitan area had embraced a pair of major-league baseball teams for 50 years, but they were now perplexed as they read about the possibility that one or both might be sold and leave town. Rumors periodically circulated either about baseball teams relocating or about a third league forming to satisfy the growing number of cities wanting professional baseball. Lou Perini, the beleaguered owner of the Boston Braves, certainly made baseball fans think about other deserving locales when he voiced his concerns and projections to The Sporting News: “The country is ripe for (a third major league). Eventually it is going to happen. Such cities as Houston, Toronto, Montreal, Milwaukee, and the areas surrounding San Francisco and Los Angeles can support one.”5 During a late-summer automobile trip to the Southwest, Saigh listened to a solid financial proposal from Houston investors for the sale and transfer of the Cardinals to Texas. Saigh declined their overture and stated, “The Cardinals have been nurtured through the years by a tremendously loyal audience in the Midwest area. So long as it’s within my power, I’ll never desert St. Louis for the money involved in any proposed transfer. No, money would not be the deciding factor. There would have to be other considerations more important, considerations I don’t care to go into.”6

As January 28, 1953, the time to defend himself in court, approached, Saigh remained committed to St. Louis. After consultation with his lawyer, Saigh, not wanting a lengthy jury trial, decided to switch his plea from not guilty to nolo contendere in hopes of a lighter sentence. His decision backfired in the worst way when the judge, in a surprise judgment, sentenced him to 15 months in federal prison and fined him $15,000. Saigh staggered toward the bench and pleaded that his aged mother would be alone, but Judge Roy Harper snapped at him and reminded him what his no contest meant.7 Harper, who had once been employed as the business manager of a lower-level Cardinals farm club,8 showed no favors and gave Saigh four months to get his personal and business affairs in order before his sentence began.9

Saigh met with Commissioner Ford Frick in New York during the winter meetings, and later announced that he would divest himself of his treasured ballclub for the good of baseball. The commissioner agreed with Saigh’s plan to appoint a three-member committee of civic-minded people from St. Louis to run the club until the sale. Frick acknowledged his admiration for the embattled Saigh. “He is doing this to spare baseball any repercussions and we salute him for it,” the commissioner said. “He certainly was entitled to bow out of baseball with all the grace possible under these unfortunate circumstances.”10

Veteran Cardinals All-Star Stan Musial said he understood that “business was business,” but added that he felt sorry for Saigh and wondered what was down the road for the team.11 The beleaguered Saigh analyzed several local bids for the Cardinals, but determined that none of them would work out. Just before spring training in 1953, a Milwaukee syndicate swiftly worked themselves in as the front-runners to buy the club. A sale approved by National League owners would result in the franchise being transferred to the “beer and cheese capital” in Wisconsin. It was early February and Saigh knew he had little time left to get a purchase arrangement that he felt was acceptable, so he told his St. Louis office employees that they would be paid for moving expenses and compensated for losses selling their homes since it appeared Milwaukee would be acquiring the team.12

As Saigh prepared to return to the Big Apple to meet with Frick and get the sale to the Milwaukee group approved, he was suddenly asked to postpone his trip because a new St. Louis entity was prepared to negotiate with him. Saigh agreed to halt his business plans after he learned that David H. Calhoun, president of St. Louis Union Trust Company, and James P. Hickok, executive vice president of First National Bank, were representing Anheuser-Busch to discuss a sale of the Cardinals to the brewery. The two well-known area businessmen, who had both been considered for the commissioner’s approved three-person civic committee, convinced Saigh that Anheuser-Busch had a serious interest in acquiring the ballclub to keep it in St. Louis. Saigh laid out his request to Calhoun and Hickok and stated that he would take less money than the Milwaukee group had offered. (It was later announced to be about $4 million.13)

A deal was readily consummated and a 6:00 A.M. press conference to announce the sale agreement was scheduled for February 20 at First National Bank downtown. The early hour was to allow the St. Louis Post-Dispatch to fully report the proceedings in its evening edition.14 The elaborate session was staged in the bank’s sixth-floor directors room. In addition to local newspaper and wire services, area radio and television stations were there. As the “changing of the guard” commenced, Saigh stood and opened with a timeline to describe how the Anheuser-Busch offer to purchase the team and keep it in St. Louis had been conveyed to him.15

Fifty-three-year-old August A. Busch Jr., president of the brewery, would assume the same role with the Cardinals on March 11 after a vote by the Anheuser-Busch stockholders. Busch began his formal statement with these words: “During its 100 years of existence, Anheuser-Busch has shared in all St. Louis civic activity. The Cardinals, like ourselves, are a St. Louis institution. We hope to make the Cardinals one of the greatest baseball teams of all times, and we propose to further develop our farm clubs.” William Walsingham Jr., the nephew of the late Cardinals owner Sam Breadon, would retain his position as vice president and operating head of the baseball organization. Several directors of Anheuser-Busch and legal counsel of the brewery were in attendance. This was the first time that the Cardinals would be owned by a corporation rather than a single owner or a small group of investors. Busch said the Cardinals would not sell stock to the public.16

National League President Warren Giles journeyed from Cincinnati to be present at the proceedings and had already approved the transaction between Saigh and the brewery. Giles said: “The sale of the Cardinals was appropriate and beneficial to St. Louis, the Cardinals and the National League. It was appropriate that an institution like Anheuser-Busch would identify itself with the Cardinals. I am glad to welcome Busch and his associates to the National League and to baseball.” Giles was quizzed about any obstacles from other team owners and responded that he saw no problem with approval of the sale. He said that had the Cardinals been sold to someone who wanted to relocate the club, it would have been necessary to receive unanimous consent from all National League clubs to move forward.17 Although Busch was known as a sportsman within the high-society circles, it was with show horses and hunting clubs, so the personal welcome to the sport of baseball from Giles was beneficial.18 Longtime comrades and acquaintances referred to Busch as “Colonel” or “Gus,” which is what he preferred over “Augie” or “Gussie.”19

Saigh appeared very subdued after his initial narrative of the transaction, but he did answer several questions pertaining to monetary details of the sale. The total financial outlay from Anheuser-Busch was headlined as $3.75 million with Saigh receiving $2.5 million, which was what he had requested. Busch confirmed that the brewery would assume $1.25 million in debt, and Saigh acknowledged that he had deposited $1 million in escrow to guard the new ownership against additional liabilities. Busch seemed well informed as he replied to myriad queries with short but ardent responses. He said the Anheuser-Busch purchase of the Cardinals was done completely from a sports angle and was not a product sales weapon, and that he would honor the rival Griesedieck Brothers beer-sponsorship contract of Cardinals radio broadcasts. Sportsman’s Park was not part of the transaction since it was owned by the Browns, with whom the Cardinals had a secure stadium lease guaranteed through 1960. Busch wished the Browns luck in the coming season and said he hoped they remained in St. Louis. Busch indicated that he would be active in the management of the Cardinals, and he endorsed incumbent manager Eddie Stanky. He said he would be heading to St. Petersburg, Florida, soon to watch the team participate in spring training.20

KSD Radio, owned by the Post-Dispatch, taped the press conference and scheduled a playback of the event for 7:00 P.M.21 KSD-TV, also owned by the newspaper, filmed an interview to be broadcast later in the morning introducing Busch. KSD special-events director and newscaster Frank Eschen was flanked on his right by Saigh, with Saigh’s attorney just behind him. Busch and Warren Giles stood on Eschen’s left as the interview commenced. Eschen first received a concise statement from Saigh that he had indeed sold the Cardinals. As Eschen shifted to move the microphone and speak to Busch, Saigh forlornly placed his hands on his hips, bowed his head, and slipped off-camera to his right, but apparently had his escape pathway blocked. Saigh looked back to see that his lawyer had turned left and was squeezing awkwardly behind the three men who were in front of a large backdrop curtain. With no option to move out of the way, an obviously distraught Saigh drooped his shoulders and followed his attorney for an unplanned “out with old, in with new” scene as the camera rolled and Eschen’s dialog continued.22

Eschen commented, “Now, congratulations are in order for you, Colonel Busch, for the fine thing that you have done in buying the St. Louis Cardinals.” Busch replied, “Well, thank you very much. We are delighted to be the owners of the Cardinals, and we are going to start to give the fans everywhere the finest baseball that is known in the United States.” Eschen concluded, “Well, I’m sure that you will fully live up to the old Cardinal tradition.”23 Busch had little time to process what Eschen might have meant by “the old Cardinal tradition” because a brewery associate had leaned in to inform him that he and his entourage were late for a tour of the administrative offices at Sportsman’s Park and to meet several employees of the ballclub.

Busch excused himself and returned to the room where the papers had been signed to retrieve a fountain pen. Unknowingly, he walked in on Fred Saigh sitting alone at the table, with his hands over his face, sobbing. Busch never told anyone about witnessing this until years later.24 As Busch entered the car for his ride to the ballpark, he thought back to how he eventually sold the idea of purchasing the St. Louis Cardinals to the brewery’s board of directors the week before. He had convinced them with an entirely different vision than what he had stated at the morning’s press conference. When Busch concluded the closed-door presentation to the brewery leaders, he emphatically predicted, “Development of the Cardinals will have untold value for our company. This is one of the finest moves in the history of Anheuser-Busch.”25

Meanwhile, team officials had contacted Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky at St. Petersburg during morning spring-training drills. Stanky, starting his second season as the Redbirds’ skipper, was asked to be in his office at Al Lang Field for a phone call in the early afternoon. With no knowledge of what had taken place in St. Louis, he assumed a player deal was in the making. When Stanky answered the telephone, it was Fred Saigh on the line explaining that he had sold the club to Anheuser-Busch. Stanky asked Saigh if he was satisfied with the deal, and Saigh replied in the affirmative. Stanky, who was under contract through 1954, responded to Saigh, “Then it’s all right with me. I’m very sorry, as you know, that you had to do this.” Stanky was grateful to Saigh for giving him his first opportunity to manage a major-league club, saying later, “Our relations were extremely pleasant. There was never one iota of interference with the operation of the club on the field. If my relations with the new owners are half as good as they were with Mr. Saigh, it will be 100 percent satisfactory.” Stanky also spoke briefly to Busch and John Wilson, an officer of the brewery, and said he was happy for them before inviting both to the club’s training camp.26 Busch had affirmed earlier that he felt Stanky was one of the best managers in the game.27

Player reaction to the sale ranged from reflective to tongue-in-cheek. Veteran second baseman Red Schoendienst recalled, “Before Busch bought the Cardinals, he had Stan and I and [traveling secretary] Leo Ward out to his hunting lodge for lunch. We were talking about the ballclub, and what was going happen to the franchise, and both Stan and I suggested that Busch buy the team. His response was that he didn’t know much about baseball, but I wonder if he already had been thinking about it and just wanted to see what our reaction would be.”28 A pair of unidentified St. Louis players were a bit loose with their retorts. “I guess if we go into a tailspin, they’ll call us the ‘Busch’ team of the league,” said one. Another jokingly said, “I always liked that Budweiser. Hey, do you think they’ll take the Redbirds off our uniforms and put beer bottles there?”29

Busch got to Sportsman’s Park for his planned visit to the team headquarters nearly an hour late. Bill Veeck had been waiting in his Browns office for a courtesy visit from Busch, but now, pressed for time, he took it upon himself to walk over to the Cardinals outer offices to meet his new intracity rival. Busch was summoned and the two owners warmly shook hands. Veeck said, “It’s nice to have you. We’re glad to see you. But I’m afraid you’re going to offer us some difficult competition.” Busch replied with a grin, “You’re right.” Glancing around the workplace surroundings with piqued interest, Veeck offered, “You know this is the first time I’ve ever been in this office.” Busch replied, “Well, it’s my first time too.” Noting that he had an apartment in the ballpark, Veeck said, “You know I live right next door, you must come and see me.” Busch responded, “You bet your sweet life I will. You’ve got to come see me and we must visit each other often.” With that, the two men shook hands again, and Veeck departed for a downtown appointment. 30

As he moved rapidly through the two floors of the Cardinals offices, Busch’s main interest in the building was whether it was fireproof. He looked closely at the names on the large blackboards and listened intently as Cardinals scout Joe Monahan and minor-league director Joe Mathes explained the rosters and the method by which players were transferred from one team to another. Busch posed for several pictures with team employees. Fred Saigh, who was present for the orientation, declined to be in any of the photographs.31

In his last act as owner of the Cardinals, Saigh went to St. Petersburg on March 8 to talk with Stanky, watch a game against the New York Yankees, and speak briefly with the players about the sale.32 Busch had ventured to Hot Springs, Arkansas, for 10 days’ rest before traveling to Florida to see his squad in action. Busch donned a Cardinals cap and uniform shirt, grabbed a bat, and took some practice swings against relief pitcher Eddie Yuhas. When he did not connect with the soft tosses delivered by Yuhas from about 30 feet away, Stanky cracked that Yuhas might find himself on another club if Busch didn’t hit the next one.33 Busch delivered a clubhouse talk to the team, attended games, and visited the Cardinals’ minor-league camps in Daytona Beach, Florida, and Albany, Georgia.34 Since a slight rift had developed in St. Petersburg regarding the Cardinals’ lease, Busch met with Mayor Sam Johnson and local baseball ambassador Al Lang to get a new agreement in the works to continue at the longtime spring training facility.35

Busch returned to St. Louis to make an early April inspection of Sportsman’s Park before the season began, and demonstrated that he had not paid much attention to his surroundings in the few times he had attended a major-league baseball game in St. Louis. After scrutinizing the grim conditions of the concession areas and the restrooms, he rasped, “I’d rather have my ballclub play in Forest Park.”36 Busch was appalled at how small and decrepit the ballpark seemed, and lectured associates about how ashamed he would be to bring his friends out to the ballpark. An angry Busch made a list of demands to his landlord to fix the place up, but Veeck said that he had no money to do anything.37 The warmth the men had shown several weeks earlier had just turned frigid, and the future of “Baseball in St. Loo’” would quickly shift to an unforeseen, but predictable pathway.

RUSS LAKE lives in Champaign, Illinois, and is a retired college professor. The 1964 St. Louis Cardinals remain his favorite team, and he was distressed to see Sportsman’s Park (aka Busch Stadium I) being demolished not long after he attended the last game there, on May 8, 1966. His wife, Carol, deserves an MVP award for watching all of a 13-inning ballgame in Cincinnati with Russ in 1971 — during their honeymoon. In 1994, he was an editor for David Halberstam’s baseball book “October 1964.”

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org/bioproj, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record. Additional websites accessed were newspapers.com and stltoday.com.

Notes

1 Stan Musial, as told to Bob Broeg, The Man Stan: Musial, Then and Now (St. Louis: Bethany Press, 1977), 139.

2 Evault Boswell, “The Bad News Browns,” Missouri Life, May 2016. missourilife.com/life/the-bad-news-browns/, accessed September 15, 2016.

3 Ray Gillespie, “Bill Veeck Is ‘Trying to Laugh Brecheen Case Out of Court,’ Says Fred Saigh, Filing Charges,” The Sporting News, November 12, 1952: 9.

4 “Saigh to Put His Baseball Future Up to Frick, Giles; Indicted on Tax Charge,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 24, 1952: 1.

5 Clif Keane, “Perini Gives Hub Two Years to Back Braves,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1952: 1, 6.

6 Bob Broeg, “Houston Bid for Major Club Five Years Too Early – Saigh,” The Sporting News, November 5, 1952: 7.

7 Bob Broeg, Memories of a Hall of Fame Sportswriter (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1995), 218.

8 Ray Gillespie, “Judge Who Sentenced Saigh Was Card Farm Executive,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1953: 12.

9 Ray Gillespie, “Owner Given 15 Months, $15,000 Fine,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1953: 11.

10 Dan Daniel, “Saigh Studies Flock of Bids for Cards,” The Sporting News, February 11, 1953: 5.

11 Musial as told to Broeg, 148.

12 Rob Rains, The St. Louis Cardinals, the 100th Anniversary History (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992), 128.

13 “Cardinals Ball Club Sold to Anheuser-Busch,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 20, 1953: 4.

14 Broeg, Memories of a Hall of Fame Sportswriter, 219.

15 “Cardinals Ball Club Sold.”

16 Ibid.

17 “Cardinals Ball Club Sold to Anheuser-Busch Inc. by Fred Saigh for $3,750,000,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 20, 1953: 1.

18 “New Cardinals President Busch Long Active in Field Sports,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 20, 1953: 4.

19 Broeg, Memories of a Hall of Fame Sportswriter, 221.

20 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 20, 1953: 1.

21 “Cardinals Ball Club Sold.”

22 Video Production, St. Louis Cardinals, A Century Of Success, 100 Years of Cardinals Glory (St. Louis Cardinals and Major League Baseball Properties, Inc., 1992).

23 Ibid.

24 Peter Hernon and Terry Ganey, Under the Influence, the Unauthorized Story of the Anheuser-Busch Dynasty (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 212.

25 Hernon and Ganey, 213.

26 J. Roy Stockton, “Cardinals Look Forward to New Owner’s Visit to Florida Training Camp,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 21, 1953: 6.

27 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 20, 1953: 1.

28 Red Schoendienst with Rob Rains, Red: A Baseball Life (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 1998), 71.

29 J. Roy Stockton, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 21, 1953: 6.

30 “August Busch Jr. Visits Cardinals’ Offices, Takes Over March 11,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 21, 1953: 1.

31 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 21, 1953: 4.

32 Dan Daniel, “Saigh, in Farewell to Game, Foresees End of Two-Club Ball in Three Cities,” The Sporting News, March 18, 1953: 9.

33 Red Byrd, “‘We’re Behind You on Every Play,’ Busch Assures Cards,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1953: 11.

34 Red Byrd, “Busch Inspects Cardinals’ Farm Camp at Albany, Ga.,” The Sporting News, March 18, 1953: 9.

35 Frederick G. Lieb, “‘Busch Heals St. Pete Rift With Redbirds,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1953: 11.

36 Broeg, Memories of a Hall of Fame Sportswriter, 221.

37 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis, A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Avon Books, Inc., 2000), 405.