Aquino Abreu: Baseball’s Other Double No-Hit Pitcher

This article was written by Peter C. Bjarkman

This article was published in Spring 2014 Baseball Research Journal

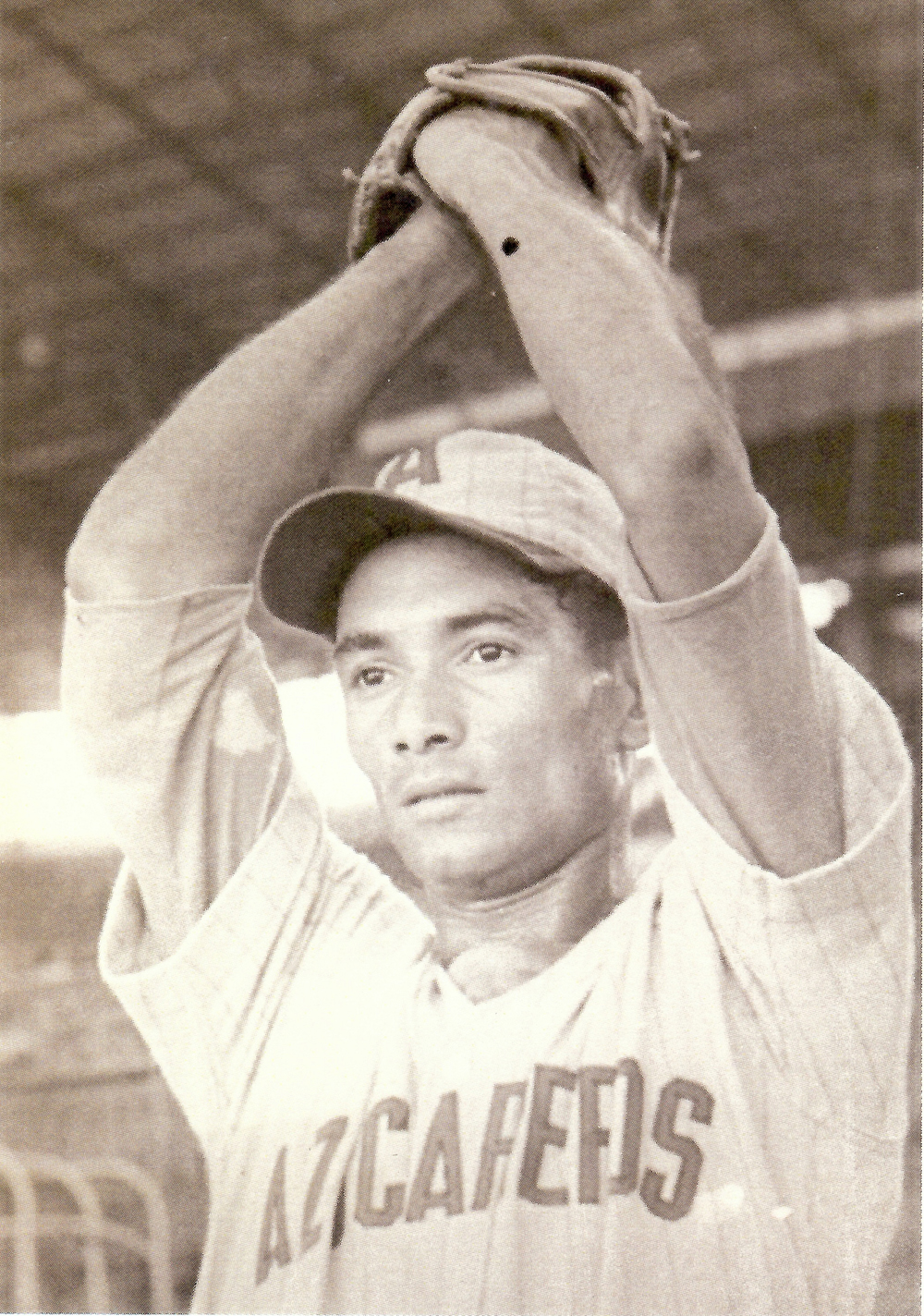

Aquino Abreu in the uniform of the 1968–69 National Series champion Azucareros ball club, three seasons after his miraculous three-game pitching string. (Author’s Collection)

Aquino Abreu—a diminutive right-handed fastball specialist who labored for a decade and a half during the formative years of the modern-era post-revolution Cuban League—remains entirely unknown to North American and Asian baseball fanatics. This is a rather large irony considering that Abreu once registered a string of the most remarkable performances witnessed anywhere in the history of the bat-and-ball sport. The more noteworthy event perhaps was a pair of consecutive no-hit and no-run games in 1966 that equaled a feat achieved precisely once in the big leagues and perhaps only five in the entire recorded saga of North American Organized Baseball. Hardly less rare, however, was this same obscure hurler’s 20-inning losing stint that same season in which he rang up 19.1 scoreless innings before yielding the sole enemy tally in the final frame. And all three miraculous performances were achieved in less than the span of a single month. It is hardly an exaggeration to propose that no other single pitcher in the game’s long annals ever matched Abreu by authoring a similar trio of brilliant outings during any single brief four-week span.

No ballpark history buff worth his salt is unaware of Cincinnati southpaw Johnny Vander Meer’s pair of back-to-back gems against Boston and Brooklyn in June of 1938; it is a feat that only two other major league pitchers—American Leaguer Howard Ehmke of Boston in 1923 and National Leaguer Ewell Blackwell of (quite ironically) Cincinnati in 1947—have ever come legitimately close to matching. More obscure were the consecutive hitless games achieved in May 1952 by Bill Bell of Bristol (Tennessee) in the Class D Appalachian League.1 With his own pair of unique uninterrupted gems in January 1966, Abreu thus became the first to display this same form of unparalleled pitching mastery anywhere outside of North American soil.

Baseball history is full of short-term wonders that flash for a week or a month or even a season but soon fade away to mediocrity, and Abreu was one of the prototype examples. At the end of a 14-year career, the native of Cienfuegos Province owned an overall losing lifetime record. He did boast a few moments of overseas glory earned with the Cuban National Team long before that outfit had established itself as an invincible dynasty in international tournament play. But he never stood out among the Cuban League pitchers of his own era, let alone the legendary mound aces that would follow in succeeding decades. Yet in one brief ten-day stretch of January 1966, Abreu accomplished a pitching oddity that remains indelible in the annals of island baseball lore. He joined the equally overachieving Vander Meer as the third member of baseball’s most exclusive pitching club—the only three hurlers in major professional league competition to author consecutive no-hit and no-run games. (Clarence Wright achieved the feat in 1901, in the Western Association.) But one huge downside was that the Cuban also paralleled Vander Meer’s own uneven career in so many less illustrious features.

Abreu was one of the earliest notable figures of Cuba’s post-1960 baseball, although his brief fame rested more on a few spectacular moments than on any sustained performances. In his fourteen seasons he only posted four campaigns in which his victory totals exceeded his numbers in the loss column.2 Only once did he reach double figures in wins (10–1 during his most stellar season of 1968–69)—a feat balanced out by another later season in which he also lost just as frequently (owning a 5–10 mark for the 1973–74 winter campaign). Perhaps Aquino’s proudest boasting point in retrospect was that his ERA totals fell under 2.00 in exactly half of his career National Series outings; but it must at the same time be noted that those campaigns came in an era famed for pitching dominance and filled with rather miniscule ERA numbers. Abreu himself never paced the circuit in the ERA department, and no circuit leader in the Cuban League ever soared above the 2.00 level until 1988 (the league’s twenty-seventh year of existence).3

Given the relatively mediocre set of career numbers and the obvious absence of any semblance of lasting star status, Abreu’s slot in Cuban baseball lore is indisputably built upon his singular streak of hitless magic during the second month in Cuba’s fifth season of baseball action in the Fidel Castro era. But those two surprising no-hitters were not by any stretch the sum total of Abreu’s achievement, nor the only mark of his stature in the early going of Cuba’s new brand of amateur-style national pastime. Less than a month before his two masterpieces, the Centrales right-hander also hurled twenty masterful innings in a single contest. He also enjoyed several stellar outings on national teams that were at the time laying a foundation for Cuba’s eventual dominance in international play. And he was arguably one of the most solid hurlers in the league’s early years even if he rarely stood among the island’s year-end statistical leaders.

Little is known publicly about Abreu’s early life away from the baseball diamond, other than the fact that his origins were those of the largely impoverished farming class that populated central Cuba during the decade immediately preceding World War II. Tomás Aquino Abreu Aguila was born in the rural agricultural distinct of southern Cienfuegos Province—in the village of San Fernando de Camarones—on March 7, 1936. The island population during that era was still recovering from a bloody U.S.-backed 1933 revolution that had successfully unseated the ruthless dictatorship of President Gerardo Machado but also first brought to prominence future strongman Fulgencio Batista. Abreu’s father Lupgardo Abreu Gómez and his mother Petrona Aguila Arbolaez both hailed from a poverty-stricken peasant stock that then constituted the bulk of the island’s rural population. Aquino would eventually marry twice (the second time in 1958) and would sire three sons (all with his first spouse, Maria Cuéllas). His offspring were named Francisco Abreu Cuéllas (the eldest), Reinaldo Abreu Cuéllas, and Pedro Abreu Cuéllas (youngest). The remainder of Abreu’s private life remains altogether obscure since his rare public comments have always been narrowly focused solely on his substantial 1960s and 1970s athletic career.4

Prompted by interviewers Leonardo Padura and Raúl Arce in 1989 to comment about his three sons and their own baseball ambitions, the ex-pitcher’s answers were somewhat evasive. Only the middle son, Reinaldo, apparently harbored early baseball ambitions. “He was also a pitcher and accounted himself well as a youth, but he had to give it up,” Abreu observed. “He is now a physical education professor, but the others followed different paths: the elder is an engineer and the younger is a minor official with FAR [an acronym for the Cuban Armed Forces]. Even if they didn’t become ballplayers the most important thing is that they are happy and that I am proud of them all.” But why Reinaldo had to relinquish his own pitching dreams (because of injury, perhaps, or because of lack of talent?) is never revealed by the self-described proud father.

In that same 1989 interview (based on my own translations from the Spanish), Abreu would also provide only sketchy details concerning his own start on the amateur diamonds of rural Cuba in the middle decade of the twentieth century. “I always dreamed of being a ballplayer, of appearing on television, of wearing those fancy uniforms, and of being popular, and cheered for. But despite those dreams I never thought I could play in the organized leagues, or even less that I could represent Cuba overseas. But it all came true and therefore today I am hugely satisfied.”

Abreu would also inform his 1989 interviewers that his earliest memories were of weekend games in local pastures where he and his buddies played barefoot and without any formal equipment outside of a rubber-taped ball and crudely carved bat. A pitcher from the outset, young Abreu was invited in 1950 at age 14 to play on a neighboring village club from Cumanayagua during the regional juvenile championships. He had apparently drawn some local attention as a hard thrower although he admittedly knew very little at the time about the art or science of pitching. Early success in these local youth tournaments eventually led to a spot in the Liga Azucarera (Sugar Mill League) where he would debut in 1958 for a club sponsored by the Central Manuelita (Manuelita Sugar Mill). By 1960 he was working for the Cienfuegos Province Hanabanilla hydroelectric plant and also pitching weekend games for the local Cumanayagua ball club in the island’s popular Amateur Athletic Union League.

The opening decade of a new post-revolution brand of national baseball in Cuba was one full of pomp and circumstance—with a strong measure on patriotism and politics thrown in for good measure—even if the quality of play did not always quite measure up to earlier professional Cuban winter league standards. Most of the best native professional prospects playing with the island’s AAA International League franchise quickly abandoned their homeland once the Havana Sugar Kings ball club was overnight transferred to Jersey City in July 1960. Among the native Cubans on the 1960 Sugar Kings roster, Leo Cárdenas, Miguel Cuéllar, Orlando Peña and others were all destined to be future big leaguers. A number of additional stellar players with professional prospects (Pedro Ramos, Camilo Pascual, Tony Oliva, Zoilo Versalles, Luis Tiant, Jr., Bert Campaneris, Cookie Rojas, José Tartabull, Tony Taylor, José Valdivielso, and Tany Pérez, among others) had all departed for the States immediately before or shortly after Castro’s forces seized government control in January 1959.

A final professional winter league season was played in Havana with only native Cuban professional players in 1960-1961, in the immediate aftermath of the Sugar Kings uprooting. Most of those Cubans (including already established big leaguers like 1961 Cuban League MVP Pete Ramos and his Washington teammates Camilo Pascual and Julio Becquer) rejoined their North American clubs in the spring of 1961 and almost none returned after tensions escalated between the governments in Havana and Washington.5 A seven-decade-long tradition of professional winter play in Cuba was suddenly over, but a new type of baseball would soon emerge on the horizon. And it would be rebuilt on the backs of a considerable army of “lesser” talents (mostly denizens of the popular country-wide amateur and Sugar Mill leagues) who had remained at home on their native island.

Part of Castro’s plan for overhauling Cuban society and launching a “fairer and more just” societal order (one founded upon Soviet-style Communist principles) involved the total revamping of the island-wide organized sports system. Sports and recreation—like education and health care—would now become a genuine “right of the people” and not an enterprise for profit-oriented commercial business. A revamped government agency labeled with the acronym of INDER (Institute for Sports, Education and Recreation) was founded in February 1961 and under its direction all professional sports were outlawed across the country (with the famous National Decree 936) by the middle of the same year. There would now be no admission charges for attending such public events as ball games and concerts; attending matches and ballgames would become a popular celebration aimed at entertaining and building community spirit. Baseball would now involve only native Cubans (no more imported foreign talent) in a new kind of national league with a prime focus on developing strong home grown and patriotic national squads.

The new National Series league opened play in January 1962, with only four clubs that recruited their talent from the popular amateur leagues of the previous decade. Amateur leagues (especially the Amateur Athletic Union league and the various Sugar Mill circuits) had always been highly popular and now they would no longer take a back seat to a pro league featuring mainly visiting North American professionals. The first few seasons would be played with only a handful of teams but by the end of the first decade there were a dozen squads spread across the island and no longer restricted (as the former pro circuit was) mainly to Havana.6 For the first time Cuba could enjoy not only a purely indigenous brand of baseball but also a genuinely “national” sport that was staged in all of the island’s (at the time) six provinces.

One motive for the new league was to supply and train players for a national team that could carry the Cuban banner into the international arena and thus display the imagined strengths of the socialist (non-commercial) brand of baseball. If Castro had been deeply stung by the loss of the AAA-level Sugar Kings he was now bent on launching a novel system designed to beat the Americans at their own “national game” in the venues of international tournaments. At the very time the April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion was unfolding, a handful of the top amateur Cuban players (soon to be showcased in the new league) were already winning a first proud victory in nearby Costa Rica. The surprisingly robust Cuban amateur squad went undefeated en route to capturing a cherished gold medal during that spring’s fifteenth edition of what was then called the Amateur Baseball World Series.7

Early National Series baseball was also highlighted to a notable extent by staged political displays of yet another flavor. Castro himself would regularly make celebrated appearances at the first several opening-day league festivities. It was arranged for “El Comandante” himself to slug out the first official base hit of the inaugural league game on January 14, 1962 (he tapped a fat delivery from Azucareros starter Jorge Santín through a cooperative infield) and this staged ritual was subsequently carried on for the next several seasons.

It was into this brand of new revolutionary baseball that Aquino Abreu emerged during the first National Series of winter and spring 1962. Performing for the Azucareros (Sugar Harvesters) under manager Antonio Castaño, Abreu would collect 4 of the 13 overall wins for his second-place ball club. If that total seems small, the schedule was short (27 games) and even the most successful league pitchers posted only a half-dozen games in the win column. Abreu would register six starts that first season and leave the field as the pitcher of record in all six (two defeats and three complete games). The diminutive but hard-throwing righty logged his first league victory on February 8, 1962 in Havana’s Latin American Stadium, a complete-game six-hit 5–0 shutout of rival Habana, the eventual league cellar-dweller.

Aquino’s decade-plus career displayed few true highlights, although those few were spectacular enough to carve out a lasting legend. His physical stature on the mound was also something less than imposing and his successes would eventually result more from a carefully honed craftsmanship than from any element of raw power or exceptional arm talent. Years later he would comment to Padura and Arce that although at the outset of his career in the early sixties he had already mastered an adequate fastball and tricky curve, it was lessons learned from the tutoring of 1940s-era amateur league great Pedro “Natilla” Jiménez (ironically then the manager of the rival Orientales National Series club) that opened the door on his eventual successes. It was Jiménez who painstakingly instructed Abreu on how to mix up the speeds of his deliveries and also impressed upon him the necessity of concentrating on the specific weaknesses of each and every rival batter.

Despite early promise and his developing mastery of the pitcher’s art, Abreu would became a celebrity hurler only in the immediate aftermath of his rare feat achieved during the early going of his fifth league season (which he entered with only a lackluster 10–16 record to date). Suddenly he was seen as more than just a run-of-the-mill league pitcher, despite the fact that those two inexplicably odd no-hit games would account for two of his three victories during the campaign. With a 3–2 won-lost mark but only nine earned runs permitted, he would rank second that year in the individual ERA department, the closest he ever came to leading the league (his 1.50 mark trailing the 1.09 registered by 1961 World Cup hero Alfredo Street). Abreu’s mark on the 1966 season—especially his runner-up ERA numbers—perhaps seem all the more impressive in light of the fact that his Centrales club finished dead last in the six-team circuit with a 23–40 record.

The first no-hitter came on a Sunday afternoon: January 16, 1966. Centrales hosted the Occidentales club in Santa Clara’s venerable Augusto César Sandino ballpark (now the home stadium of the current league powerhouse Villa Clara Orangemen). The visiting club (with most of its players hailing from Pinar del Río Province) featured outfielder Fidel Linares, a solid early league performer in his own right but also the father of future league star Omar Linares (now dubbed by many followers of the international game as the best third baseman never to play in the Major Leagues).

That inaugural no-hitter (the opening match of a scheduled twin bill) was an unsettlingly one-sided affair from the start and a regrettably sloppy game by almost any standards. The home contingent jumped far out in front with four markers in the first and a half-dozen more in the third and coasted easily from there to a 10-0 whitewashing. The outclassed losers not only failed to connect for a single safety but also committed an embarrassing six errors before the afternoon was out. Under little pressure after the third frame, Abreu struck out four and issued three free passes along the way. Another base runner reached on an error (second baseman Mariano Alvarez’s boot of an infield roller by the game’s third batter, the aforementioned Linares). Yet if the game was not very artistic it was nonetheless hugely historic. It was the first no-hitter witnessed in the six short years of league history.

Abreu spoke wistfully a quarter-century later (to Padura and Arce) about a sore limb that failed to deter him during his first effort. He apparently was not aware that he had been pitching flawlessly until the fact was pointed out to him in the eighth by catcher Jesus Oviedo. But this violation of baseball superstition was not nearly as troubling in the final frames as was an increasingly painful right arm. By game’s end Aquino was unable to lift the sore limb above his shoulder and it continued to throb and ache until his next scheduled start. Here apparently could be found the origins of serious and lasting arm troubles that would plague the ill-starred hurler for the remaining decade of his professional career.

The second no-hitter would follow nine full days later (teams then played only four or five times a week). The January 25 evening date with destiny would be set in Havana’s cavernous Latin American Stadium and the opposition would be eventual league champion Industriales, already the island’s most beloved team. This contest was far cleaner, with the losers only booting the ball twice, but it was also equally one-sided on the scoreboard. Again Abreu benefitted from the comfort of an early lead (a pair of runs in the first and a 7–0 cushion after five) and coasted home despite struggling a bit with his control. He struck out seven but also issued half-a-dozen walks, the control lapses likely being the result of the painful pitching limb that still plagued him severely.

According to the pitcher’s own later report he felt sound during pre-game warm-ups, and he seemed pain-free (after nine days of suffering) until the fifth inning. But from the fifth on, he had to abandon his more effective fastball and rely on a prayer and his soft breaking balls to get by in the clutch. He would also report that the second no-hitter was largely a product of considerable luck. Not only was he laboring with a wounded appendage but he was also rescued by a pair of remarkable late-inning fielding plays—by Alvarez and shortstop Ramón Fernández—that both saved likely base hits.

With the final out (a tame roller to second by outfielder Eulogio Osorio) Abreu had accomplished the unthinkable by duplicating the feat first achieved by Vander Meer 28 seasons earlier. And as was the case for Vander Meer (who had walked the bases full before finally escaping his own final history-making inning at Ebbets Field), a truly historic repeat performance for the Cuban Leaguer had been anything but a clean or easy affair.

The two games would remain a lofty mountain peak in an otherwise rocky career. Laboring for the renamed Las Villas club one season later, “Mr. No-Hit” would be saddled with a 3–6 record. The same would occur (6–8) when he returned to the Azucareros club a year after that. But by the 1968–69 campaign Abreu would enjoy a sudden upswing and a surprising return to prominence. His 10-1 mark was one of the league’s best and his ERA again dipped below 2.00 (as it would four more times before his career finally wrapped up). For steady year-long achievement, 1968–69 (NS #8) was definitely a “career” season. Abreu would also enjoy moderate successes across two following campaigns, going 6–3 and 6–1 while still wearing the Azucareros jersey. But in 1974 (back with Las Villas) he lost a career high ten matches (versus five wins), and his final two seasons saw his innings on the mound dip drastically (to 38.0 and then to 22.1) as his career quickly faded.

The overall career that surrounded the two no-hitters was in the end anything but remarkable. A victory total of 62 would average out to less than five wins per season; a career 2.26 ERA is only impressive if it is removed from the context of the era in which he labored. A half-dozen Cuban League mound stars boast sub-2.00 lifetime marks and a full dozen (some from later more hitter-friendly decades) are under 2.20 for a full ten-year-plus career. There were far greater pitchers during the same pioneering era, even if none of the others enjoyed three quite-such-brilliant single outings. In the end the best that can be said is that Abreu’s overall mound record is somewhat blunted since it came during an era of remarkable pitching that marked the Cuban League’s own “dead-ball” period.

But the no-hitters were enough to clinch a legend since they put Abreu in the rarest of company alongside Vander Meer—even if few would know anything about his feat in the larger outside baseball universe that existed beyond a Cuban island now largely closed to outside scrutiny by Castro’s revolution. There are some quite interesting parallels between the two pairs of no-hitters. The duo by Abreu comprised the first two no-hitters of any type in Cuban League history. Vander Meer’s second was spiced by the added fact that it came in the first ever Ebbets Field night game (also the first night contest in the baseball capital of New York City), itself a first-rate historic occasion. Abreu’s second (also a night game) was the first ever in the venerable Havana ballpark that has over the years now hosted the largest number of such games on the island (13 of the 51 Cuban no-hitters have occurred in Latin American Stadium; the next most are six in Santa Clara’s Augusto César Sandino Stadium, also the site of Abreu’s first gem).

Abreu’s overall career would also parallel that of Vander Meer in rather ironic fashion. Both men were career sub-.500 pitchers. Vander Meer won and lost more or less equally in the majors (119–121) and the minors (76–73). Abreu also dropped more league games than he won in domestic competition (62–65 overall, 55–59 in 14 National Series, 1–2 in one Selective Series, 6–4 in one Special Series). Yet Vander Meer did enjoy the big stage when he pitched in both the All-Star Game (1938 as the game winner, also 1942 and 1943) and the World Series (1940). Abreu was on three different occasions one of the aces of the Cuban national team in international tournament play, essentially the Cuban version of pitching in the Series.

And it can also be noted that both pitchers struggled with control during their second no-hit efforts and across their full careers. Plagued by wildness throughout much of his career, Vander Meer was exceptionally sharp when he walked only three (against four Ks) in his initial masterpiece versus Boston on June 11, 1938. But in the more memorable Ebbets Field outing the Cincinnati southpaw almost didn’t survive the ninth when he walked the bases full before dodging a bullet with Leo Durocher’s final fly ball to short center. In that historic second game, Vander Meer not only walked eight Dodgers but also benefitted from superb defense by Lew Riggs on two potential base hit grounders and a spectacular outfield grab by Wally Berger. Abreu had an identical line of three free passes and 4 Ks in his first but permitted six hitters to reach the base paths due to his own wildness in the second. And again he also benefitted by a pair of late-inning fielding gems.

Many writers have labeled Vander Meer’s feat as the most unbreakable record in baseball, since a hurler would need to complete an unimaginable three straight hitless nine-inning outings to best it. Before Abreu worked his magic far off the North American radar screen in the invisible Cuban League, only two other big leaguers came tantalizingly close to equaling what Vander Meer alone had done.8 In one respect, however, Abreu actually outdid his big-league forerunner since his gems occurred directly on the heels of a marathon 20-inning effort that serves to make them all the more remarkable.

From a purely artistic perspective, it might be suggested that Abreu’s greatest outing was actually the one that preceded his pair of no-hit games. The durable Centrales ace pitched all 20 frames of a marathon game that at the time was the longest in Cuban League history. In that December 28, 1965 affair at the Sports City Park in Santiago, Abreu took the hill against the Orientales and threw 19 scoreless innings, facing 66 batters before the match was finally decided. But on that ill-starred day the four opposition pitchers were just as effective and the scoreless contest stretched on for more than four nail-biting hours. Abreu struck out 13, while allowing a dozen enemy hits and also walking seven. But he would lose it all by relinquishing the game’s lone run with one out in the bottom of the twentieth. The inning’s second hitter, Elpidio Mancebo, electrified the partisan crowd with a loud double. Then after an intentional walk to set up a possible double play, Gerardo Olivares finally ended the extended day by slapping a single into right field.

Within the space of less than a month, then, Abreu would not only toss his back-to-back no-hit games, but he would also throw a 19 1/3-inning stretch of shutout baseball, a far more difficult feat. And the earlier stunt may well have come at a steep price, since the arm problems that plagued Abreu in his next two historic outings and throughout his career might well be traced to his marathon effort in December.9 There have been many big league no-hitters (nearly 300) but how many big-league hurlers have blanked the opposition for 19 straight frames in a single outing? One recalls only a National League duel between Brooklyn’s Leon Cadore and Boston’s Joe Oeschger who battled for 26 frames in the 1920s and allowed but a single run each along the way, or Joe Harris, who pitched 20 straight scoreless innings in September 1906.10

Abreu’s success was not exclusively limited to his three days of exceptional mastery. He also made his brief mark on the world tournament scene when Cuba was first establishing its international dominance. His first such outing—on the heels of his National Series debut season—came at the August 1962 Central American Games staged in Kingston, Jamaica. Overall it was a less than successful return to that event by the Cubans after a dozen-year absence; the young and inexperienced club managed by short-tenured big leaguer Gilberto Torres lost three heart-breakers to the Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, and Mexicans sandwiched around victories over Colombia and Venezuela. Abreu appeared in relief on two occasions, worked six total innings, gave up a single earned run, struck out one batter while walking four, and earned no game decisions. When asked in 1989 about his fondest baseball memory he suggested without hesitation that it was the first time he heard the national anthem while wearing a national team jersey in Jamaica (and not either of his later no-hitters).

During the April 1963 Pan American Games in Brazil, both the Cuban team and Abreu himself performed far more brilliantly. Seven victories against a lone defeat brought home a gold medal and Abreu was a game winner on two occasions—twice beating host Brazil with complete game victories, 11–2 and 17–3. An even more impressive triumph came on the heels of his double no-hit season when in June 1966 he again labored on the staff of Cuba’s championship squad at the Tenth Central American Games staged in Puerto Rico. The latter tournament was held against a backdrop of severe political tension and the Cuban delegation was purposely detained long enough upon arrival by ship at San Juan Harbor to miss the event’s official opening ceremonies. During the games, anti-Castro exiles heaved stones at Cuban players on the diamond interrupting action on several occasions. Abreu earned a complete-game 5–2 victory over the hosts in the opener (he made one other brief appearance in relief) and Cuba walked off with another gold medallion on the strength of a second decisive victory over Puerto Rico in the finals.

In his 1989 interview with Padura and Arce, Abreu recalls receiving several lucrative professional offers during the 1966 stay in San Juan to leave his homeland and join North American professional ball clubs. As Abreu remembered it, “There was a great effort to buy a number of our players and I got several offers, including 30,000 pesos to sign with Pittsburgh. They even put in the paper that I had signed for 50,000 pesos, but it wasn’t true and in the end none of us on the team stayed in Puerto Rico.”

In the final analysis, perhaps the biggest irony attached to Abreu’s Jekyll-and-Hyde career was the fact that his consecutive gems were also the very first pair of such games in Cuban League history. The young Cuban League had survived its first four-plus seasons without a single hitless ballgame before witnessing a flood of eleven such masterpieces over the next four campaigns—with five in 1967–68 (two on the same day) and three more the following year. And it should also be noted here that no-hit games transpire far more infrequently in

Cuba than they do in the majors.11 This fact has held up both throughout early league history when pitchers were most dominant and also later decades (especially the aluminum bat era) when hitters tended to rule the day.

After retiring from pitching, Aquino continued working as a baseball instructor and pitching teacher at the lower levels of Cuba’s highly organized and community-based athletic training system. In 1974 (during his final National Series season with Las Villas) he opened the Manicaragua’s Baseball Academy based at the local “Escambray” ballpark in his hometown, a rural outpost in central Las Villas Province about twenty-five miles east of his birthplace in neighboring Cienfuegos Province. Abreu also served briefly as a coach for the Azucareros (a team for which he had played in seven different campaigns); he also managed the Arroceros for a single season in 1976–77, guiding his 20–19 charges to a ninth-place finish in the 14-team circuit. That single managerial season was also notably the first year in which the Cuban League employed aluminum rather than wooden bats (a tradition that would last until 1999).

Settled in Manicaragua, the quiet and unassuming ex-ballplayer remained entirely out of the limelight for the next three and a half decades. The considerable hoopla surrounding a Golden Anniversary (fiftieth) National Series season in 2010–11 brought little media attention to Abreu’s pioneering achievements, yet he did reemerge in public for a lengthy Havana national television interview in April 2012 during a pre-game broadcast before the second contest of an Industriales-Ciego de Avila championship play-off series. In that most recent interview, the still-hearty 76-year old veteran spoke eloquently about his skills in dominating early-era league hitters, his own particular philosophy of pitching, and the vast differences between the athletes of his own time and the modern-day era.12

In the end one has to be careful about equating Abreu’s achievement with that of Vander Meer. Although the Cuban League has emerged in recent decades as a world-class venue ranking only below the majors (and perhaps also the Japanese Central and Pacific Leagues), this was certainly not the case during the era in which Abreu pitched. Cuba’s top stars of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s (the era when IBAF tournament play featured aluminum bats) earned stellar reputations in international circles largely by drubbing amateur squads composed mainly of university all-stars or pro-league rejects. Had they chosen to leave their homeland, few Cuban Leaguers of Abreu’s decade would have been able to crack big league rosters or even AAA lineups. Nonetheless, tossing 18 straight innings of no-hit baseball at any level—such a feat depending as heavily as it does on the mere bounce of the ball and the undeniable role of raw luck—is indeed miraculous. That fact is strongly supported by the equal rarity of such a feat at any level of organized baseball action.

When Cuban League fans and enthusiasts today speak of the great hurlers of the past half century they are quick to recall such indelible figures as Rogelio García, Braudilio Vinent, José Ariel Contreras, Pedro Luis Lazo, José Antonio Huelga, and numerous others of the past half-century. Even the most well-informed of Cuban native diehards today have little memory of Abreu; his international reputation pales alongside more prestigious feats performed on the international stage by such legends as Huelga (decorated by President Castro after an heroic 1970 IBAF World Cup victory in Colombia over the Americans and future big leaguer Burt Hooton), Contreras (owner of an unblemished 13–0 mark in top-level international tournaments before abandoning Cuba for a solid big league career), or the more recent Lazo (who’s 2006 stellar bullpen effort against celebrated Dominican big leaguers vaulted Cuba into the finals of the first World Baseball Classic). But if what Abreu once accomplished has seemingly been relegated to the dustbin of Cuban League history, it can never be entirely erased. So far his rare performance has not been matched and it will most likely never be topped. And as the very first to achieve a remarkable no-hit rarity Abreu can also therefore never be entirely replaced in the pages of Cuban baseball history.

PETER C. BJARKMAN is a widely recognized authority on Cuban baseball past and present, an avid collector of Cuban game-worn uniforms, and a frequent visitor to the island nation. His work as a “Cuban baseball insider” has been featured on Anthony Bourdain’s Travel Channel episode of “No Reservations Cuba” (2011) and also with a 2010 front page profile story in the “Wall Street Journal.” He is the Senior Baseball Writer for www.BaseballdeCuba.com, the leading Cuban League website.

Sources

Alfonso López, Felix Julio. Con las bases llenas: Béisbol, historia y revolución. Havana, Cuba: Editorial Cientifico-Técnica, 2008.

Barros, Sigfredo. “La hazaña de Aquino Abreu,” Granma 51 Serie Nacional Webpage (http://granma.cubaweb.cu/eventos/51serie/noticias/html)

Bjarkman, Peter C. A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864–2006. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2007. [especially Chapter 8: Cuba’s Revolutionary Baseball (1962–2005)]

Bjarkman, Peter C. “Vladimir Baños Provides First No-Hitter of Cuba’s Golden Anniversary Season,” internet column for www.BaseballdeCuba.com (December 28, 2010) (www.baseballdecuba.com/newsContainer.asp?id=2345)

Bjarkman, Peter C. “Cuban League Witnesses Historical “Schiller Rule” Tandem No- Hitter,” internet column for www.BaseballdeCuba.com (March 14, 2012) (www.baseballdecuba.com/newsite/NewsContainer.asp?id=2763)

Garay, Osvaldo Rojas. “La inedita hombrada de Aquino Abreu,” Blog de Las Avispas de Santiago de Cuba (http://lasavispas-sc.blogspot.com/ 2011/01/la-inedita-hombrada-de-aquino-abreu.html)

Green, Ernest J. “Johnny Vander Meer’s Third No-Hitter,” Baseball Research Journal, Volume 41:1 (Spring 2012), 37–41.

Guia Oficial de Béisbol Cubano 1966 (National Series VI). Havana: Editorial Deportes (INDER), 1966.

Guia Oficial de Béisbol Cubano 2010–2011 (National Series L). Havana: Editorial Deportes (INDER), 2012.

Johnson, Lloyd and Miles Wolff (editors). The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. Second Edition. Durham, NC: Baseball America, 1997.

Padura, Leonardo and Raúl Arce. Estrellas del Béisbol. Havana: Editorial Abril, 1989. (Chapter 5: “Aquino Abreu ” sin hits ” ni carreras,” p. 74–83.)

Stang, Mark. “Matching Johnny Vander Meer “.. a pair of near misses,” Mark Stang Baseball Books, July 27, 2009 (http://markstangbaseballbooks.com/node/62)

Toledo Menéndez, Dagoberto Miguel. Béisbol Revolucionario Cubano, La Más Grande Hazaña—Aquino Abreu. Havana: Editorial Deportes, 2006.

Notes

1. In his Spring 2012 SABR BRJ article on Johnny Vander Meer, Ernest Greene acknowledges Bell’s Appalachian League accomplishment and observers that it was “thought to be the first such feat in the minors since 1908.” (Bell’s games were tossed on May 22 against Kingsport and May 26 versus Bluefield.) But the evidence is not at all clear on this matter. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Second Edition, Johnson and Wolff) records that Walter Justus—pitching for Lancaster in the Class D Ohio State—racked up four no-hit games in 1908 (likely itself some kind of record). These fell on July 19, August 2, September 8 and September 13 (the final two only five days apart). But Johnson and Wolff do not indicate consecutive starts in their 1908 no-hit listings as they do for Bell’s games in 1952. And at any rate, the Class D Ohio State League of 1908 was probably in no way parallel to the leagues in which Vander Meer, Bell, and Abreu labored. It is also to be noted that Vancouver’s Tom Drees threw consecutive hitless games (May 1989) in the Pacific Coast League in the late-eighties, but since the first of those two games was a 7-inning affair (first game of a doubleheader) it does not qualify as an “official” legitimate no-hitter by the standards now recognized throughout baseball.

2. During the half-century of modern-era Cuban League play, numerous calendar years (especially during the decades of the 1970s and 1980s) have contained more than one “season” of league play. The winter National Series has frequently been followed by such additional late spring or summer campaigns as the Selective Series (1975–95), the Revolutionary Cup (1996–97), the Super League (2001–05), the All-Star Series (1968–65, 1979), the Special Series (1974–75), and the Series of Ten Million (1970). These extra campaigns on occasion have been longer in duration than the National Series itself, but the latter has traditionally been considered the true Cuban League “season” since it has been staged every year without interruption since 1962. A full explanation of the Cuban League structure and the variations in length of seasons is found in my SABR BioProject entry on “The Cuban League” (http://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/cuban-league).

3. During Abreu’s decade and a half career, the league ERA leaders posted totals of under 1.00 on seven different occasions. During the stretch of 11 campaigns between 1970 and 1980, only on one single occasion did the league leader post a mark of 1.00 or above, and the highest league-leading figure of the circuit’s first 26 campaigns was the 1.67 posted by Camagüey’s Andres Luis in 1985 (135 innings pitched). The first league leader to soar above the 2.00 mark was Rogelio García in 1988. Admittedly Cuban League pitchers enjoy shorter seasons which may work to their advantage. But clearly the period spanning Abreu’s career fell within Cuba’s own “dead ball” era in which the pitchers consistently dominated league hitters (and this remained the case for more than a decade after aluminum bats were first introduced for league play in 1976).

4. Dagoberto Miguel Toledo Menéndez’s single sketchy biography published in Cuba in 2006 contains virtually nothing of Abreu’s personal life story. The only lengthy published Abreu interview (found in a 1989 collection of player portraits published by novelist Leonardo Padura and sports journalist Raúl Arce) is one in which the ex-pitcher speaks mainly of his baseball pedigree and of amateur league feats in his early youth. Only one segment of that interview refers to Abreu’s three sons and there is no mention at all of his parents or any siblings. (It might also be noted here that the village of Abreu’s birth lies less that 20 kilometers due south of the equally quaint crossroads town of Cruces, site of an obscure family tomb containing the remains of Cooperstown Hall-of-Famer Martin Dihigo.)

5. Among the small handful of active professionals who opted to remain in Cuba after termination of the MLB-affiliated winter professional circuit, the most notable were Fermin (Mike) Guerra (nine-year veteran big league catcher whose career with the Washington Senators ended in 1951) and Tony Castaño (14-year winter league veteran outfielder/ infielder who had been the manager of the 1960 Sugar Kings up to the time of their removal from the island on July 13, 1960). Both Guerra (Occidentales) and Castaño (Azucareros) would serve as managers in the 1962 inaugural National Series season.

6. The four-team National Series was expanded for the first time to six teams in 1965 (fifth season), then to a true island-wide dozen in 1967 (seventh season). The number of league teams would soar to as many as 18 in the mid-eighties, but a current 16-team arrangement (with the single exception of 2011–12 with 17 clubs) has been the rule for all of the past quarter-century.

7. Cuba dominated Amateur Baseball World Series events in the 1940s and early 1950s (with seven titles, one silver medal, one third-place finish, and four non-appearances). But during (and largely due to) the political island upheaval caused by the Castro revolution, the IBAF-sponsored tournament went on hiatus until the 1961 renewal in San José. Mass tryouts in Havana produced an exceptionally strong team (led by star amateur league pitcher Alfred Street) for the first international competition after the installation of the Castro government. In a quirk of fortuitous timing the Cuban entry ran roughshod over their nine opponents at precisely the same moment when Castro’s army was repelling a United States-backed home-front military invasion at the Bay of Pigs.

8. Writing on his personal blog site, Mark Stang details the near double no-hitters (one earlier and one later) that left both Boston’s Howard Ehmke and Cincinnati’s Ewell Blackwell an eyelash short of preceding and following Vander Meer. Ehmke earned no-hit fame on September 7, 1923 in Shibe Park by allowing only two Philadelphia runners to reach base (an error and a walk). The no-hitter seemed something of a fluke since Athletics pitcher Slim Harris seemingly doubled in the sixth but was ruled out for failing to touch first base. Also an eighth-inning error by outfielder Mike Menosky was first ruled a hit but quickly changed to an error by the official scorer. If Ehmke had plenty of help in that game he was not so fortunate in the follow-up outing at New York when the first Yankee batter of the opening inning reached on a muffed grounder to third that was generously ruled a hit. Ehmke would then shut down the opposition without another safety for the 3–0 victory. In June of 1947 Blackwell (just like Vander Meer a decade earlier) would no-hit the Boston Braves in Crosley Field. Facing the Dodgers (another irony) five days later Blackwell was only two outs short of the his own double no-no when Eddie Stanky ruined the magic with a liner that bounced through the pitcher’s own legs into center field. Stang’s accounts of these games are highly relevant here as solid illustrations of just how much luck and rare circumstance is involved in achieving what so far only Vander Meer and Abreu have managed.

9. Abreu told Padura and Arce that his arm woes actually could be traced back to the 1963 season (his second National Series) and stayed with him throughout the rest of his career. He claims he could hardly throw in 1964, but a year later the nagging injury seemed to improve. He mentions that this surprise improvement allowed him to last for 19-plus innings in one contest (the one under discussion). He also remarks that he felt “borracho” (drunk) by the end of that marathon contest and it is most likely that the recurring pain during the no-hitter came from a re-aggravation during that very 20-inning stint.

10. Three Cuban League hurlers have since tossed 20 complete innings in one outing: Mario Vélez (March 21, 1983 for Las Villas versus Orientales), Féliz Nuñez (for Orientales in the same game), and Roberto Domingéz (November 23, 1986 for Henequeneros versus Industriales). The latter effort by Domingéz actually came in a relief effort. It might be noted here that while Oeschger hurled 21 straight scoreless frames and Cadore 20 in the more famous big league game (May 1, 1920), both did so only after earlier yielding a single run in the first six innings of that contest.

11. Cuba has celebrated 53 no-hit games in an identical number of National Series seasons (including three multiple-pitcher efforts but only a single perfect game by Maels Rodríguez in 1999); in the dozen-plus seasons of the new millennium there have been 12 such games in Cuba. The big leagues by contrast have provided 31 no-hitters (and seven perfect games) over the same limited span, seven in 2012 alone (three perfect games) and six in 2010 (two perfect games). The 279 official nine-inning gems in the majors since 1903 equates to better than 2.5 per MLB season, compared to a 1.1 no-hitters per season ratio for the Cuban League. Granted that Cuban League seasons over the years have been on average only about half as long as MLB campaigns and include more teams, the ratio still tilts slightly in favor of the majors when it comes to the ease of no-hitter achievement. I discuss this comparison of no-hit games in the two leagues at length in my articles (both cited above) of December 28, 2010 and March 14, 2012 published on-line at www.BaseballdeCuba.com.

12. In Abreu’s words from 1989 (translated here from the Spanish): “Our own era was very poor technically speaking. We didn’t have the resources available today and we also didn’t have players equal to the level of those active today. We also didn’t train scientifically. At the same time our baseball (in the 1960s) was more heated and action-packed. And I also think the matter of interest is crucial and it is here that something has been lost. I believe that many of today’s players just don’t give one hundred per cent on the field. We started off playing with used uniforms handed down from the Marianao and Almendares clubs of the former pro league and two of our teams—Azucareros and Habana—had totally improvised uniforms at first. We didn’t have any equipment bags or any other luxuries, but when we lost a game we didn’t even care to eat afterwards and many of the players would shed tears after losing. Things have changed from our era in many different senses.”