Arbitrator Seitz Sets the Players Free

This article was written by Roger Abrams

This article was published in Fall 2009 Baseball Research Journal

Introduction

The most important labor arbitration decision of all time involved baseball, two pitchers and one of the finest labor arbitrators of all time, a true arbitration “superstar.” His 1975 decision in baseball’s Messersmith case still reverberates throughout the multibillion-dollar sports industry. Arbitrator Seitz set the players free.

Peter Seitz was a role model for many of us who came to arbitration in the 1970s. He was a neutral designed by central casting, with flowing silver hair and a three-piece suit. His work is legendary. In 1975, as the designated permanent arbitrator under the basic agreement between Major League Baseball and the Major League Baseball Players Association, the parties asked Seitz to resolve a dispute concerning the interpretation and application of baseball’s reserve system.

Peter Seitz was a role model for many of us who came to arbitration in the 1970s. He was a neutral designed by central casting, with flowing silver hair and a three-piece suit. His work is legendary. In 1975, as the designated permanent arbitrator under the basic agreement between Major League Baseball and the Major League Baseball Players Association, the parties asked Seitz to resolve a dispute concerning the interpretation and application of baseball’s reserve system.

From the earliest days of organized professional baseball, club owners had restricted the right of players to move from club to club in order to diminish their bargaining power and restrain their salaries. A player could negotiate only with one club, the one that listed him on its “reserve list.” Other clubs could not tamper with a reserved player by offering him a more attractive salary. Unless his contract was sold, traded, or terminated, the player remained reserved forever, even after he had formally retired from the game.

This century-old personnel system would be demolished by Arbitrator Seitz. He ruled that the so-called “reserve clause” — in fact, it was a combination of provisions in the uniform players contract and the governing rules of baseball — only allowed a club to renew a player’s contract once and not perpetually.1 As a matter of policy, I agree with Seitz’s conclusion. As a matter of arbitration decision-making, I will argue that his ultimate conclusion was in error.

A few caveats are in order. First, arbitrators write opinions very quickly. Parties seek a resolution of their disputes with a statement of reasons for the results. They do not want (or need) a law review article. In this case, Peter Seitz issued his award in a matter of days — not months. He should be excused if upon reflection some feel his work was not perfect. Second, any analysis of the Messersmith award must be based on the data described in the opinion and further evidence discussed in the federal courts on appeal.2

Undoubtedly, there was more evidence before Arbitrator Seitz, although I think we can assume that he marshaled his best arguments. He knew how important this case was to the parties. He tried hard to get them to settle the fundamental issue that divided them, but without success. Finally, Dick Moss, a superb California sports lawyer who tried and won the case for the Players Association, disagrees with my analysis, as I expected he would. I value his judgment. I was not there when collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) were negotiated in 1968, 1970, and 1973, nor was I at the arbitration hearing. The written decision, however, must stand based on what it says, not on what it could have said.

The Facts and Proceedings

John Alexander Messersmith was a splendid right-handed starting pitcher. After hurling for the California Angels for five years, Messersmith was traded to the Dodgers in 1973. Over three seasons in Chavez Ravine he won 53 games and lost 41, including a 20-win, 6-loss campaign in 1974. His 12-year career statistics were an impressive 130 wins and 99 losses, with a 2.86 earned run average.

Unable to reach a new contract with its player before the 1975 season, the Dodgers organization exercised its power to renew Messersmith’s contract. At the close of the 1975 season, however, Messersmith claimed that he was a free agent because the Dodgers could no longer unilaterally extend his contract. The Players Association filed a grievance on his behalf, contending that the Dodgers no longer retained the exclusive right to employ Messersmith.3

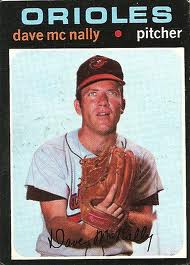

Because the Players Association was concerned that Dodgers club owner Walter O’Malley might settle the dispute with Messersmith and end the arbitration case short of a decision on the merits, it added a second grievant to its case. Dave McNally had retired during the 1975 season, completing a stellar 14-year major-league career. The southpaw had been a stalwart of the Baltimore Orioles staff, winning 181 games and losing only 113. During a four-year span from 1968 through 1971, McNally might have been the best pitcher in baseball. He won 20 or more games each year for a total of 87 wins, while losing only 31. His club was in the World Series three of those four years and won the Series four games to one in 1970 over Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine.

Because the Players Association was concerned that Dodgers club owner Walter O’Malley might settle the dispute with Messersmith and end the arbitration case short of a decision on the merits, it added a second grievant to its case. Dave McNally had retired during the 1975 season, completing a stellar 14-year major-league career. The southpaw had been a stalwart of the Baltimore Orioles staff, winning 181 games and losing only 113. During a four-year span from 1968 through 1971, McNally might have been the best pitcher in baseball. He won 20 or more games each year for a total of 87 wins, while losing only 31. His club was in the World Series three of those four years and won the Series four games to one in 1970 over Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine.

McNally finished his career with 12 appearances for Montreal in 1975, and, although he retired, the Expos retained him on its reserve list.4 He too claimed that, upon completion of his 1975 option year, he became a free agent. (McNally, of course, had no intention of returning to the game, but he agreed to participate in the arbitration, serving, in effect, as a “relief grievant.” When the case ended, he returned to his hometown of Billings, Montana, where he and his brother Jim owned and operated two Ford dealerships.)

Under the basic agreement between Major League Baseball and the Major League Baseball Players Association, a tripartite board heard all grievances. Marvin Miller represented the union, and John Gaherin the owners. Of course, the neutral cast the deciding vote. The panel heard the Messersmith case on an expedited basis. The grievance was filed on October 1, 1975, and hearings were held on November 21 and 25, and December 1. From the very start, Seitz tried to convince the parties to resolve the matter privately without his intervention. He appreciated how significant the case was in the history of the business of baseball, but his efforts to bring about a voluntary settlement failed. This case would have to go to decision, however — settlement, if any, of this fundamental dispute would have to follow an arbitration award and not precede it.

The Players Association sought an interpretation of the uniform player contract provision that allowed the club to renew the contract “on the same terms” for “one year.” In his autobiography, A Whole Different Ballgame,5 Marvin Miller, the executive director of the Players Association, explained that this contract language had always been perfectly clear to him — “one year” means “only one year.” Management, on the other hand, believed that the option clause was one of those terms in the contract that was renewed when the option was exercised. Looking only at Paragraph 10(a) of the Uniform Player’s Contract, it seems apparent to me that the Players Association had the better of the argument. The language could have been made stronger — language can always be made better in hindsight — by saying that the contract can be renewed “only once,” but, even without this modifier, a commonsense reading of the clause favored the union’s interpretation. Yet, the clause was not unambiguous. The option to renew did not exclude any of the contract provisions.

Arbitrability

Before proceeding to the merits of the dispute, Arbitrator Seitz had to answer an extremely difficult arbitrability question. The grievance and arbitration provision was of the typically broad variety. “Grievance” was defined as “a complaint which involves the interpretation of, or compliance with, the provision of any agreement between the Association and the Clubs or any of them, or any agreement between a Player and a Club . . . .”6 The clause did contain a few express exceptions to the coverage of the arbitration promise, but said nothing about disputes concerning the reserve system.7 Article XV of the basic agreement stated, however, that “[e]xcept as adjusted or modified hereby, this Agreement does not deal with the reserve system.”8 Since the agreement did not deal with the reserve system, management argued that the matter was not arbitrable, because only disputes concerning the interpretation of the provisions of the agreement were arbitrable.

Before proceeding to the merits of the dispute, Arbitrator Seitz had to answer an extremely difficult arbitrability question. The grievance and arbitration provision was of the typically broad variety. “Grievance” was defined as “a complaint which involves the interpretation of, or compliance with, the provision of any agreement between the Association and the Clubs or any of them, or any agreement between a Player and a Club . . . .”6 The clause did contain a few express exceptions to the coverage of the arbitration promise, but said nothing about disputes concerning the reserve system.7 Article XV of the basic agreement stated, however, that “[e]xcept as adjusted or modified hereby, this Agreement does not deal with the reserve system.”8 Since the agreement did not deal with the reserve system, management argued that the matter was not arbitrable, because only disputes concerning the interpretation of the provisions of the agreement were arbitrable.

All arbitrators have heard disputes where the parties say one thing in their contract but mean something else. But Article XV was a different ballgame. The basic agreement obviously dealt with the reserve system. It incorporated by reference the uniform player contract that contained the option clause and the major-league rules that set forth the system of reserve lists9 and no-tampering edicts10 that made the reserve system operate.

In his opinion, Seitz correctly found the dispute arbitrable. He explained the origin of the curious Article XV. The Players Association had proposed an earlier version of this provision when the Curt Flood antitrust suit was pending. The union sought to avoid being held liable for damages as a “co-conspirator” if Flood prevailed on his claim. Contract language to this effect was first suggested to the Association by Flood’s counsel, former Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg.11 The 1973 version of Article XV12 was placed in the agreement after the Supreme Court rejected Flood’s claim.13 This would allow both parties to argue to Congress that the agreement did not embody the reserve system.14

Arbitrator Seitz’s decision finding the matter arbitrable would later be enforced on appeal. Courts see issues of arbitrability as not requiring the deference mandated by the Supreme Court toward issues on the merits.15 The Eighth Circuit, in an opinion authored by Judge Heaney, Kansas City Royals v. Major League Baseball Players Association,16 did a careful investigation of the record before reaching its conclusion that the grievance was arbitrable:

The essence of the Club Owners’ arguments on the question of arbitrability was perhaps best articulated in the testimony of Larry [sic] McPhail, president of the American League, in which he stated: “Isn’t it fair to say that our strong feelings on the importance of the core of the reserve system would indicate that we wouldn’t permit the reserve system to be within the jurisdiction of the arbitration procedure?” The weaknesses in this argument have been previously discussed. . . . We add only that what a reasonable party might be expected to do cannot take precedence over what the parties actually provided for in their collective bargaining agreement.17

Unable to find the requisite “forceful evidence of a purpose to exclude the grievances here involved from arbitration,”18 the court enforced Seitz’s ruling.

The Merits

Arbitrator Seitz quickly disposed of the central issue on the merits. “One year,” he wrote, meant “one year.” The option clause covered a single renewal of the terms of the contract. He did not accept management’s argument that by renewing the entire contract, the club also renewed the option clause. Seitz reasoned that management’s analysis would make the option perpetual. If parties wanted to do this, they could, but it would have to be spelled out in clear and unmistakable terms in the body of the contract. In support of this proposition, Seitz relied on New York state real estate cases — not necessarily the best support for reading a CBA.

Here is where I would join issue with the esteemed arbitrator. I suggest that in reading the ambiguous contract language, he ignored the recent bargaining history between the parties and the century-old narrative of the relationship between owners (early on called “magnates”) and their players. No one at the negotiating table in 1968, 1970, or 1973 could reasonably have thought that both parties had agreed to discard their history and effect a fundamental change in the reserve system.

There is no question that Marvin Miller believed that the uniform contract allowed for only a single renewal. He certainly wanted that to be the case. If it was the case, then why had no player from 1879 — when the reserve system was first adopted by the owners — to 1973 ever “played out his option” and declared he was a free agent?19 For almost a century, players and owners acted as if the reserve system was perpetual.

Bargaining History

More to the immediate point is the compelling evidence of bargaining history explored in depth by the Eighth Circuit in reviewing the Seitz award. The court described this evidence as relevant to its inquiry on arbitrability, but it is quite telling on the merits issue as well. The first CBA between the Players Association and Major League Baseball was reached on February 19, 1968. That agreement incorporated the essential elements of the reserve system by reference. The renewal clause of the uniform player’s contract and the relevant major-league rules were made part of the agreement. Article VIII of the 1968 basic agreement provided that “[t]he parties shall review jointly . . . (b) possible alternatives to the reserve clause as now constituted.”20

In fact, the parties held three meetings to discuss the possible modification of the reserve system, but no agreement was reached. Miller later testified that no further discussions were held because the club owners refused to consider significant changes in the reserve system. Standing alone, this evidence supports the conclusion that the reserve system, as practiced previously under the renewal clause and the major-league rules, was not altered in the 1968 negotiations. No one could reasonably conclude that the union had procured a modification in that system at the bargaining table. The parties had agreed to “review” the issue jointly, shelving the matter for the duration of the agreement.

The 1970 Agreement

During negotiations over the 1970 CBA, the Players Association submitted a number of proposals to directly modify the reserve system. One proposal would have given a player the option of becoming a free agent once every three years. Management rejected the union’s proposals as unacceptable. The plan, the owners said, attacked “the heart of the game and the reserve system.”21 By February 1970, the parties had reached an impasse on any changes to the reserve system. Miller then suggested:

We are not making any progress on modifications in the Reserve System. We are running out of time, in terms of the date of the negotiations, the approach of the season, and if it is mutually desirable to make an agreement, we have got to do something about this issue that we are not making any progress on, and therefore we ought to set it aside.22

The parties also sparred over the implications of the pending Curt Flood case. That was when the Players Association proposed the following language:

Regardless of any provision herein to the contrary, the Basic Agreement does not deal with the reserve system. The parties have differing views as to the merits of such system as presently constituted. This Agreement shall in no way prejudice the parties or any player’s position or legal rights related thereto.

During the pendency of any present litigation relating to the reserve system, it is agreed that the parties will not during the term of this Agreement resort to strike or lockout on that issue. However, upon the rendering of a final court decision in such litigation, either party may upon the giving of 30 day’s written notice to the other party, reopen this Agreement and thereafter the parties may resort to any legal and appropriate action in support of their respective positions on this issue.23

Although designed to address the potential of co-conspirator liability in the Flood suit, this language plainly stated that there was a reserve system “presently constituted,” about which the parties have differing views on the merits.

The club owners counter-proposed:

Regardless of any provision herein to the contrary, this Basic Agreement does not constitute an agreement between the parties as to the merits or legality of the reserve system. This Agreement shall in no way prejudice the position or legal rights of the parties or of any player regarding the reserve system.

It is agreed that during the term of this Agreement neither of the parties will resort to any form of concerted action, or encourage or support, directly or indirectly, any claim or litigation (other than Flood v. Kuhn, et al., pending in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of N.Y.) on the issue of the reserve system, or any part thereof, and neither of the parties shall be obligated to negotiate regarding the reserve system.24

This language also assumes the existence of a reserve system, although it eliminated the reference to the parties’ “differing views” on the merits. The final language, in relevant part, embodied a sprinkle of each proposal:

The parties have differing views as to the legality and as to the merits of such system as presently constituted. This Agreement shall in no way prejudice the position or legal rights of the Parties or of any Player regarding the reserve system.25

Thus, the 1970 agreement accepted the fact that there was a reserve system “presently constituted,” and it reserved the parties’ and the players’ “legal rights” regarding this system. The parties reached agreement on May 12, 1970. Once again, that basic agreement incorporated the relevant uniform player contract provisions and the prevailing rules of the reserve system.

Management’s negotiator, Louis Hoynes, later quoted Miller as having said during those negotiations that the reserve system “is going to be outside the Agreement. It will not be subject to the Agreement, but we will acquiesce in the continuance of the enforcement of the rules as house rules and we will not grieve over those house rules.”26 Miller denied making the statement. Even if he said nothing agreeing to the continuance of the reserve system, the history of the 1970 negotiations cannot possibly be read as modifying the existing reserve system in any way. Prior to the start of the 1971 season, however, Miller told the players that, “in his view, a player could become a free agent by playing for one year under a renewed contract.”27 Based on the evidence we have, it is hard to see how he reached this judgment. It was wishful thinking, but sometimes wishes come true, as they eventually did here.

The 1973 Negotiations

Once again, in the 1973 negotiations, the Players Association brought to the table proposals to modify the reserve system. The club owners rejected all but two. One proposal was not very controversial and did not go to the heart of the reserve system.

Under the new provision, a player who had been in the major leagues at least 10 years and had played for his present club for at least the past five years could veto a trade. A second provision addressed an aspect of the new salary arbitration procedure for resolving salary disputes through final offer arbitration and raised some controversy. The owners demanded that a player and his club must execute a uniform player contract before the arbitration hearing, only leaving open the portion of paragraph 2 of the contract that sets the salary. The union objected to the application of the requirement when the player does not file for salary arbitration. Miller testified that he stated his objection as follows:

I said to the owners’ representatives, “It is clear to us what you are trying to do and it ought to be equally clear why it is not acceptable. Under the present set of restrictive rules, there is one procedure left to the player; that is, he can refuse to sign and can play under the owner’s option for one year.” I continued by saying, “What you have proposed is not only to not modify the reserve system, as we have proposed, but also to close the last vestige of rights, the right of the player to become a free agent after a one-year renewal.”28

Management negotiators had a very different recollection of Miller’s statement. They did not view Miller’s statement as relating to free agency at all. Based on previous and contemporary negotiations, if Miller had said that a player has the right to declare free agency upon expiration of a renewal year, it is likely that the club owners would have hit the roof!

The parties made no progress on any further changes in the reserve system. The bargaining impasse continued into February 1973, and the owners announced that they would lock the players out of pre-spring training, which was scheduled to begin shortly.

Miller then proposed that the parties again set aside the issue of the reserve system, much as they had done in 1970. He was concerned, however, that the agreement with that curious statement, discussed above, that “this Agreement does not deal with the reserve system”might be read to allow club owners to make unilateral changes in the system to the detriment of the players. He therefore obtained a side letter from baseball management:

The following will confirm our understandings with regard to Article XV of the Basic Agreement effective January 1, 1973:

1. Notwithstanding the above provision, it is hereby understood and agreed that the Clubs will not during the term of the Agreement, make any unilateral changes in the Reserve System which would affect player obligations or benefits.

2. It is hereby understood and agreed that during the term of the Agreement the Clubs will indemnify and save harmless the Players Association in any action based on the Reserve System brought against the Association as a party defendant.29

The first clause is of particular importance: The owners agreed not to change the reserve system. That must mean that the reserve system as operated historically continued unchanged.

As far as we know, this was the entire record of the bargaining history presented to Arbitrator Seitz in 1975. He concluded that in fact the option clause only allowed a club to reserve a player for one year. I have trouble understanding how this record justifies this conclusion. At best, the Players Association won maintenance of the status quo. That status quo could not have been a single year option renewal. That is exactly what the Players Association sought to change. It failed to do so in negotiations, but, as the saying goes, it was successful in arbitration.

Extra Innings

Obviously, there must have been something else in the record that moved Arbitrator Seitz to his conclusion. He might have thought that the old reserve system was bad policy — and I would agree. That could not have been why he acted, however. Having no choice other than to grant or deny the grievance — neither result was a better option than a private settlement — Seitz went with his experienced intuition. Perhaps he appreciated that an award for management would have calcified the reserve system forever, but that an award for the union would lead to bargaining to fine-tune any new reserve system. Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn quickly dismissed Seitz as the permanent neutral, accusing him of having had “visions of the Emancipation Proclamation dancing in his eyes.”30 It was certainly a “liberation arbitration.”

On appeal, the district court and the Eighth Circuit upheld the Seitz award on the merits using the appropriate limited standard of review under the Steelworkers Trilogy.31 Peter Seitz was interpreting the contract, and that was exactly what the parties said they wanted. The fact that the owners thought he was wrong on the merits was irrelevant on review.

Following the Eighth Circuit’s decision, the parties returned to the bargaining table. To provide an “incentive” to reach an accommodation, the owners locked the players out of the 1976 spring training. The club owners could not countenance a system where its employees could select their employers without restriction. At the bargaining table they demanded restrictions on free agency, and, perhaps to their amazement, the Players Association agreed.

Marvin Miller, that wily labor leader, understood his economics better than baseball management. There would be chaos off the playing field if every player was able to declare free agency at the close of any season after the option clause had been exercised once. Miller knew that the more willing sellers (players) in the marketplace, the lower the price (the salary). He wanted to restrict the number of players who could participate in the free agency auction to keep up the price. The deal the parties reached required a player to accumulate six years of major-league service before becoming eligible for free agency.

The rest, they say, is history. Player salaries skyrocketed, increasing sevenfold in the next decade as the free market came to baseball.32 The fears expressed by owners about baseball dynasties proved unfounded in the short run. In that first decade, ten different clubs won the World Series — the only time that has happened in the history of the century-old postseason tournament. Since that time, the parties have tinkered with their reserve/free agency system, but it has remained fundamentally unchanged.33 The old version of the reserve system under which management sets a player’s salary applies until a ballplayer is eligible for salary arbitration — in general after three years of major-league service. As long as it pays at or above the minimum salary prescribed by the agreement, the club holding the rights to the player determines the precise salary. At the final offer salary arbitration stage, arbitrators place the player within the industry wide salary scale based on his performance, selecting either the owner’s final offer or the player’s final demand. Finally, at free agency after six years of major-league service, the free market takes over, at least among those teams with the resources to participate in the high-priced auction.

Conclusion

Peter Seitz’s monumental decision in the Messersmith case changed the National Game forever. He was a wise and diligent neutral. In retrospect, perhaps the move away from the old restrictions on players was inevitable. In this light, Seitz should be applauded for being a visionary in the vanguard of change, not a customary position for a labor arbitrator, not one he asked to assume, but one that was thrust upon him by two parties unable to address their own issues. “Let the arbitrator do it,” they proclaimed, and he did.

ROGER I. ABRAMS is Richardson Professor of Law, Northeastern University. He is the author of four baseball books, including “Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law” (Temple University Press, 1998) and “The Dark Side of the Diamond: Gambling, Violence, Drugs and Alcoholism in the National Pastime” (Rounder, 2008).

Notes

1. Professional Baseball Clubs, 66 LA 101 (Seitz 1975).

2. Kansas City Royals v. Major League Baseball Players Association, 532 F.2d 615 (8th Cir. 1976).

3. The Players Association had supported the ill-fated effort of St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Curt Flood to have the federal courts overrule a half-century of precedent and declare that baseball was covered by the antitrust laws. (In its 1922 decision in Federal Baseball v. National League, 259 U.S. 200, a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that baseball was a purely “state affair” not affecting interstate commerce.) Flood had refused a 1969 trade to the Philadelphia Phillies and brought suit, claiming the reserve system violated the antitrust laws. Although he ultimately struck out in the Supreme Court, Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258 (1972), many remember Flood as a valiant champion of the players’ revolution. The Players Association next turned its attention to the grievance procedure, where victory would be theirs.

4. Under the reserve system, were McNally to return to the major leagues he could sign only with the Expos, unless his rights were transferred to another club.

5. Miller, A Whole Different Ballgame (Birch Lane Press, 1991).

6. Kansas City Royals, 532 F.2d at 618.

7. Article X(A) (1) provided:

(a) . . . disputes relating to the following agreements between the Association and the Clubs shall not be subject to the Grievance Procedure set forth herein:

(i) The Major League Baseball Players Benefit Plan.

(ii) The Agreement Re Major League Baseball Players Benefit Plan.

(iii) The Agreement regarding dues check-off.

(b) . . . “Grievance” shall not mean a complaint which involves action taken with respect to a Player or Players by the Commissioner involving the preservation of the integrity of, or the maintenance of public confidence in, the game of baseball.

(c) . . . “Grievance” shall not mean a complaint or dispute which involves the interpretation or application of, or compliance with the provisions of the first sentence of paragraph 3(c) of the Uniform Player’s Contract [Pictures and Public Appearances].

8. Ibid. at 618.

9. Rule 4-A(a) FILING. On or before November 20 in each year, each Major League Club shall transmit to the Commissioner and to its League President a list of not exceeding forty (40) active and eligible players, whom the club desires to reserve for the ensuing season; and also a list of all its players who have been promulgated as placed on the Military, Voluntarily Retired, Restricted, Disqualified, Suspended or Ineligible Lists; and players signed under Rule 4 who do not count in the club’s under control limit. On or before November 30 the League President shall transmit all of said lists to the Secretary-Treasurer of the Executive Council, who shall thereupon promulgate same, and thereafter no player on any list shall be eligible to play for or negotiate with any other club until his contract has been assigned or he has been released. Ibid. at 622.

10. Rule 3(g) TAMPERING. To preserve discipline and competition, and to prevent the enticement of players, coaches, managers and umpires, there shall be no negotiations or dealings respecting employment, either present or prospective, between any player, coach or manager and any club other than the club with which he is under contract or acceptance of terms, or by which he is reserved, or which has the player on its Negotiation List, or between any umpire and any league other than the league with which he is under contract or acceptance of terms, unless the club or league with which he is connected shall have, in writing, expressly authorized such negotiations or dealings prior to their commencement. Ibid.

11. It should be noted in passing that Goldberg was wrong in his analysis of antitrust law. If the restraint of trade was the product of collective bargaining and embodied in the CBA, it would be immune from antitrust liability. Amalgamated Meat Cutters v. Jewel Tea Co., 381 U.S. 676 (1965) (agreements reached through collective bargaining may be exempt from federal antitrust laws).

12. Except as adjusted or modified hereby, this Agreement does not deal with the reserve system. The Parties have differing views as to the legality and as to the merits of such system as presently constituted. This Agreement shall in no way prejudice the position or legal rights of the Parties or of any Player regarding the reserve system. Kansas City Royals, 532 F.2d at 618.

13. Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258 (1972), has been the subject of much critical comment. See, e.g., Abrams, Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law (Temple University Press, 1998). In short, the Supreme Court, in a 5–4 decision authored by Justice Harry Blackmun, concluded that baseball’s antitrust exemption created by the Supreme Court in 1922 (Federal Baseball Club v. National League, 259 U.S. 200 [1922]) was “illogical” and an “aberration.” Nonetheless, the Court left it to Congress to clean up the mess the Court had made. In fact, it left the dispute to Arbitrator Peter Seitz and the parties in their subsequent negotiations.

14. Louis Hoynes, counsel to the National League, testified in arbitration: “This language simply was an ambiguous, intentionally ambiguous, compromise of a point that would give both parties an opportunity to get up before a Congressional Committee and argue whether or not something had been done in the area of the Reserve System, and Mr. Miller indicated that he had a favorable reaction to that language, that he would review it and then we proceeded to other matters.” Kansas City Royals, 532 F.2d at 628.

15. We will leave to another day the issue of the appropriate judicial deference to an arbitrator’s decision on arbitrability. While the Supreme Court has stated that the question of whether there was a promise to arbitrate the dispute at hand is for a court to make (Steelworkers v. Warrior & Gulf Navigation Co., 363 U.S. 574 (1960)), I would argue that, upon review of an arbitration decision, the court should give deference to those facets of the arbitrator’s decision that involved interpretations of contract language. If arbitrators are expert “contract readers,” then that expertise encompasses both issues of arbitrability and the merits.

16. 532 F.2d 615 (8th Cir. 1976).

17. Ibid. at 630.

18. Ibid.

19. It is true that freed from the specter of antitrust liability by a foolish Supreme Court decision in 1922 (Federal Baseball v. National League, 259 U.S. 200), owners could blackball recalcitrant players. Playing out your option was not cost-free. There had been much litigation, however, whenever a rival league appeared on the scene and players served out their contracts and jumped to the other circuit. These were cases where one would have expected a player to have raised the contention that the option clause allowed for only a one-time renewal.

20. Kansas City Royals, 532 F.2d at 623.

21. Ibid. at 624.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid. (emphasis added).

24. Ibid. at 625.

25. Ibid. at 618–19.

26. Ibid. at 626.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid. at 627.

29. Ibid. at 628–29.

30. Abrams, Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law (Temple University Press 1998), at 132.

31. Steelworkers v. American Mfg. Co., 363 U.S. 564, 46 LRRM 2414 (1960); Steelworkers v. Warrior & Gulf Navigation Co., 363 U.S. 574, 46 LRRM 2416 (1960); Steelworkers v. Enterprise Wheel & Car Corp., 363 U.S. 593, 46 LRRM 2423 (1960).

32. In 1985, however, the Players Association noticed that premier free agents, like Carlton “Pudge” Fisk, were receiving no offers from other clubs until their club indicated they no longer wanted to keep the player. The union went back to arbitration before Tom Roberts and later George Nicolau and successfully proved management collusion in violation of the basic agreement.

33. Baseball management tried to reform its wage system during the 1994–95 negotiations, but without success. It proposed a salary cap, an anathema to the union. The union struck in August 1994 and then counterproposed a luxury tax that would dampen, but not eliminate, the free market of free agency. Commissioner Bud Selig cancelled the World Series (the first time it was not held since the 1904 hiatus). Frustrated at the table, the owners unilaterally implemented their salary cap scheme. The labor board found the parties had not reached an impasse in bargaining on this matter and thus determined that the union’s unfair labor practice charge had merit. Management withdrew its new cap system, then unilaterally instituted other changes that abolished salary arbitration, club-based negotiations over free agents, and the anti- collusion provision. The board again found merit in the union’s charge and obtained a Section 10(j) injunction in the Southern District of New York, before Judge (now Justice) Sotomayor. Silverman v. Player Relations Committee, 880 F. Supp. 246 (S.D.N.Y. 1995), aff’d, 67 F.3d 1054 (2d Cir. 1995). The union agreed to return to the playing field and more than two years later signed a new agreement with the owners. See generally Abrams, Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law (Temple University Press, 1998).