Army Sinks Navy With Late Score In First Football Meeting At Yankee Stadium

This article was written by Mike Huber

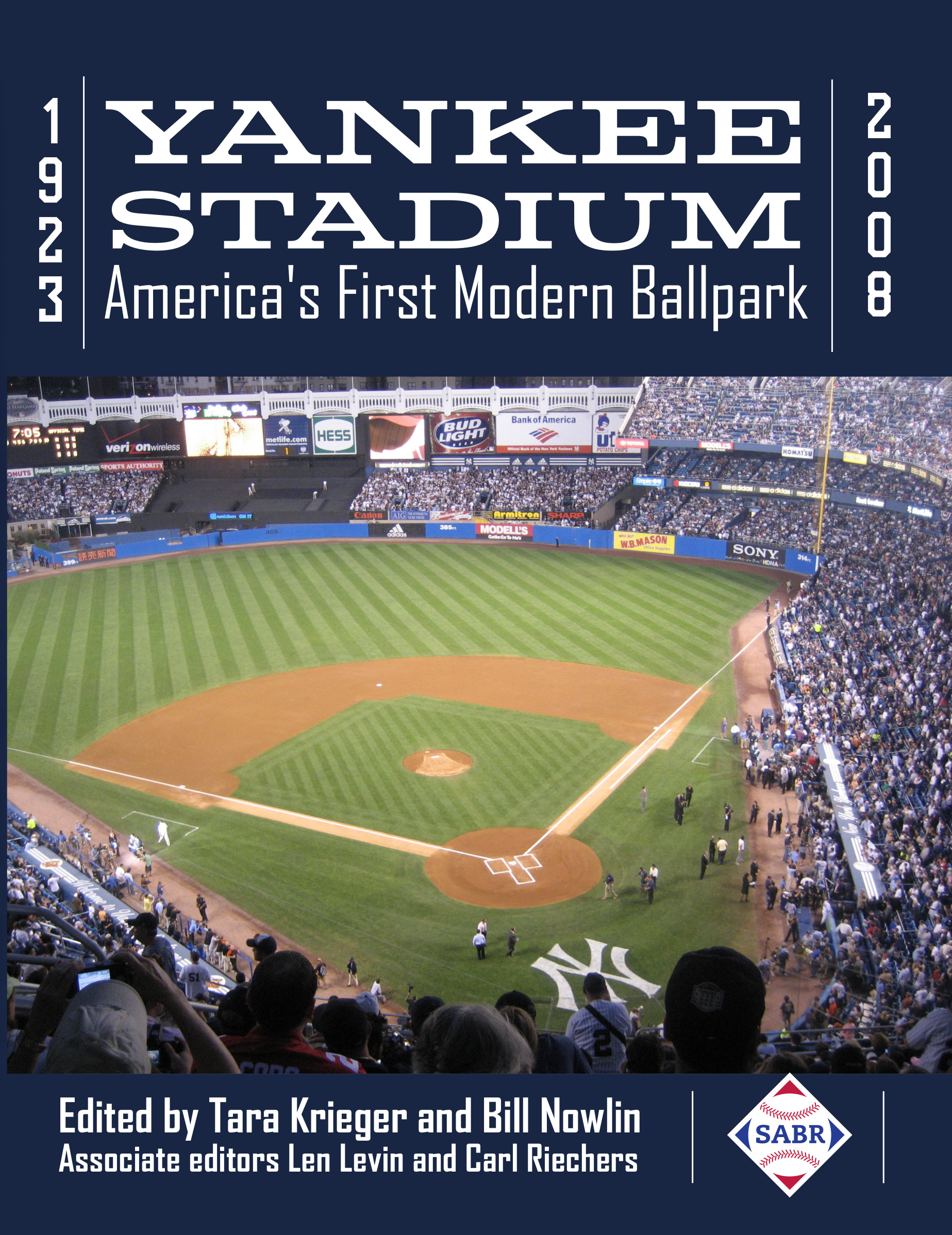

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

On a sunny day in the middle of December 1930, the House That Ruth Built was converted into a football stadium. Yankee Stadium hosted America’s Rivalry – Army vs. Navy – in a postseason football game “on the turf hallowed by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.”1

On a sunny day in the middle of December 1930, the House That Ruth Built was converted into a football stadium. Yankee Stadium hosted America’s Rivalry – Army vs. Navy – in a postseason football game “on the turf hallowed by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.”1

This was nothing new. The first football game played at Yankee Stadium took place on October 20, 1923, as Syracuse defeated Pittsburgh, 3-0, before an estimated crowd of 25,000.2 Less than a week before, in baseball, the Yankees had beaten the New York Giants to win the 1923 World Series in six games. Ruth smashed three home runs, batted .368 and posted a 1.556 OPS as the Yankees captured their very first World Series crown. In the days afterward, the diamond was transformed into a gridiron.

Army’s football team also played at Yankee Stadium. On October 17, 1925, Army battled the University of Notre Dame in the Bronx before 80,000 fans. The two teams had started an annual rivalry in 1913, played at West Point. However, West Point’s Michie Stadium (capacity 38,000) could not hold the ever-larger crowds anticipated for this game, so in 1923 Army played Notre Dame at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. The 1924 contest was held at the Polo Grounds; then, from 1925 until 1946 (except for 1930, when Notre Dame was the home team and the game was played in Chicago’s Soldier Field),3 Army battled the Fighting Irish in the Bronx at Yankee Stadium. However, it was not until 1930 that Army met its rival Navy at Yankee Stadium.

Army and Navy first met on the gridiron on November 29, 1890, playing on The Plain, the parade field at West Point.4 The tradition continued, off-and-on, through 1927. Then, on January 8, 1928, it was revealed that the superintendents of both academies (Rear Admiral Louis M. Nulton of Annapolis and Major General Edwin B. Winans of West Point) had met in Washington on January 7. The two schools were unable to reach an agreement pertaining to the three-year eligibility rule for their players and “mutually agreed that the Army-Navy game for 1928 [would] not be played.”5 The impasse was not prevented the next year, either, so the heretofore annual rivalry was canceled again in 1929.

So Army and Navy did not have each other marked on their schedules when the 1930 football season began. Economic struggles facing the country forced a change, however. America was in the Great Depression, with millions of people out of work. Thus, the two teams forgot their differences, so that “the hungry might be fed, the homeless sheltered!”6 Proceeds from an exhibition game were to benefit the Salvation Army, “for the relief of the unemployed.”7 A capacity crowd (reported at 70,000) welcomed the rivalry’s return on December 13, 1930. This was the first time the two teams had played each other at Yankee Stadium,8 and “there were no vacant patches visible anywhere in the towering steel stands or the broad reaches of the open bleachers.”9

Army sported a record of 8-1-1. Under their first-year head coach, Major Ralph Sasse, the Cadets had shut out their previous opponents six times, and in their one defeat (November 29 to Notre Dame), they had fallen 7-6.10 In those 10 games, Army had outscored its opponents by a total of 262 to 22.11

Navy had not beaten Army since 1921.12 Now, in their fifth season under head coach Bill Ingram, the Annapolis Eleven had won six of its 10 regular-season games, four by shutout. This game against Army was to be a defensive battle; scoring would be difficult and both sides knew it.

To start the pageantry, 1,200 cadets from West Point marched onto the field, “rolling steadily through the portal and spreading over the field to stand finally a motionless picture of military precision.”13 Then came the 2,000 midshipmen, who filled the entire field. The weather was “glorious.”14 The New York Times reported, “The trumpets and the flourish of military swank, the bands and the hoarse, never-ending shouting of the corps of cadets from West Point and the regiment of midshipmen from Annapolis completed the picture.”15

Approximately one hour before kickoff, “hostilities commenced”16 as the mascots, Army’s mule and Navy’s goat, were brought onto the field. Suddenly, the mule lifted a front foot and brought it down onto the goat’s head, causing the Navy mascot, although unharmed, to “beat a hasty retreat.”17

The team captains, Bob Bowstrom for Navy and Charles Humber18 for Army, met at midfield for the coin toss. Navy won19 and elected to defend the north goal. Army received the kickoff.

As anticipated, much of the game was played in a scoreless tie. West Point’s Thomas Kilday caught the opening kick at Army’s 7-yard line and raced 23 yards before being tackled. The offense drove down the field, ultimately reaching Navy’s 20-yard line before yielding the ball. Navy’s first possession started in disaster. The snap was sent skidding 19 yards behind the quarterback, where “the frantic [Lou] Kirn clutched it and fell on it one yard from his own goal.”20 For the rest of the first quarter, the two teams “see-sawed up and down the field in fitful spurts as if regulated by invisible green and red traffic lights.”21 Army gained yardage but could not push the ball over the goal line. The first quarter ended with Army in possession at midfield again, but neither team had scored.

In the second period, “the elevens waged a punting duel.”22 Navy could not move the ball. Each time Navy attempted a long pass, the ball was “slapped down by alert Army secondaries.”23 Army established one promising drive, but it ended in an interception. The ball had been in Navy’s territory for much of the first half, which ended in a scoreless tie. Navy had not yet made a first down.

The third quarter was no different. Army made a few first downs, but the third period ended still in a tie. The good news for Navy was that it was able to keep Army off the scoreboard. With eight minutes left to play in the game, however, Army quarterback Wendell Bowman took the snap and “thrust the ball into the belly of Cadet Ray Stecker,”24 who “faked giving it to another Army back,”25 then burst through the right side of Navy’s defensive line “to the distant goal where a late afternoon sun slanted through the stands of the Yankee stadium.”26 Touchdown, Army! Charles Broshous attempted a drop-kick for the extra point, but he missed. West Point led, 6-0.

Navy had a chance to win the game on its final possession. Army’s Bowman fumbled a punt on his own 37-yard line, and Navy recovered. The offense drove 12 yards, but was stopped on downs. Army took over and advanced to the Navy 7-yard line as time ran out. Army had won its 16th game in this rivalry.

The Cadets finished with 238 yards of total offense, compared with 86 for the Midshipmen.27 Army had gained 182 yards with 12 first downs on the ground, compared with Navy’s 63 yards and three first downs. The game produced 25 total punts, seven fumbles (each team lost only one fumble to the other side), and 110 penalty yards. Yet the game was a success; “No game of football has ever yet been played with teams so ready, down to the last man, to give everything.”28 That spirit has come to describe many of the contests in this storied rivalry.

Afterward Coach Sasse praised his team, saying, “For absolute unselfishness of spirit I have never seen a bunch like this one. It has been an inspiration to work with them.”29 Sasse further praised the opponent, saying that Navy “was a fine team and gave us the opposition we looked for.”30

Likewise, Coach Ingram commended his Navy players: “I’m delighted with the fight the boys showed. It was fight, fight, fight from the start and the Navy can feel proud of the game our boys put up. We were overpowered by a bigger and stronger team. But they can’t say heads down to me.”31

The game was a financial success. Ticket sales exceeded $600,000, which “would go to the Salvation Army fund for the unemployed, most of it to be used to relieve conditions in the city.”32 In addition, an autographed football was auctioned off, bought by the Salvation Army’s Commander Evangeline Booth, for $5,000.33

The famed and fierce football rivalry continued in 1931, played once again at Yankee Stadium. In an action-packed 60 minutes, Army won, 17-7. Since 1930, the two teams have competed on the fields of friendly strife annually, just not again at Yankee Stadium.

MIKE HUBER joined SABR in 1996, when he first co-taught a Sabermetrics course at West Point. In the many years that followed, he would often take his class to Yankee Stadium, to meet with the Yankees’ staff, tour the Stadium, sit in the dugout and appreciate all that the Yankees have accomplished. He enjoys writing for SABR’s Games Project and has been rooting for the same American League East team since 1968.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, much of the play-by-play was taken from the following sources:

Danzig, Allison. “Army-Navy Contest Described in Detail,” New York Times, December 14, 1930: S3.

Powers Jimmy. “Army Gets Navy Goat, 6-0,” New York Daily News, December 14, 1930: 86, 88.

Lewis, Perry. “Hazleton Lad Runs 57 Yards to Score as 70,000 Look On,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 14, 1930: 41, 42.

Amazingly, audio-video footage of the event (from MyFootage.com), including the touchdown score, can be found online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zlKeTemjOXM. Accessed July 2022. The television was invented in 1927, so this is a major achievement in the early days of TV broadcast.

NOTES

1 Perry Lewis, “Hazleton Lad Runs 57 Yards to Score as 70,000 Look On,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 14, 1930: 41, 42.

2 “Football Games at Yankee Stadium,” found online at http://www.luckyshow.org/football/ys.htm. Accessed July 2022. A total of eight football games were played at Yankee Stadium in 1923, including the Navy’s Atlantic Fleet Championship, when on December 9 the USS Wright team played to a 6-6 tie against the USS Wyoming squad. For the next several years, New York University played its home football games in the Stadium. In addition, the New York Yankees football team (also known as the Grangers) began playing at Yankee Stadium in 1926. The NFL’s New York Giants played all of their home games at the Stadium from 1956 to 1973.

3 Instead of playing Notre Dame at Yankee Stadium in 1930, Army hosted Illinois on November 8, defeating the Fighting Illini 13-0, before an estimated 74,000 fans.

4 The Midshipmen prevailed, 24-0, and one of America’s most traditional football rivalries had begun. The next three years saw the venue alternating between The Plain and Navy’s Thompson Stadium in Annapolis. See “Army-Navy Game Scores,” found online at the Naval History and Heritage Command website, https://history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/heritage/customs-and-traditions0/navy-athletics/army-navy-football-game.html. Accessed July 2022. Navy won three of those first four encounters. No games were played between 1894 and 1898, and when the rivalry resumed, the two teams agreed to play in Philadelphia, which is roughly equidistant from the two academies. In 1909 Army suddenly canceled the rest of its season after Cadet Eugene Byrne, a left tackle, died in a game against Harvard on October 30. An Associated Press story told readers, “The army is accustomed to death, but not in this deplorable form, and this tragedy of the gridiron has brought such poignant grief to officers and cadets alike that the end of football at West Point and Annapolis is predicted by many.” No games were played in 1917 or 1918, due to World War I, but the series resumed again in 1919. See Deb Kiner, “110 Years Ago, the Army-Navy Football Game Was Canceled After the Death of a Cadet,” found online at the PennLive website, www.pennlive.com/sports/2019/12/110-years-ago-the-army-navy-football-game-was-canceled-after-the-death-of-a-cadet.html. Accessed July 2022.

5 “Officials Cancel Army-Navy Game.”

6 Lewis.

7 “Notables Present at Service Game,” New York Times, December 14, 1930: S1.

8 The football teams of Army and Navy had competed at a stadium in New York City before, on several occasions. The two squads played each other at the Polo Grounds nine times, between 1913 and 1927. Army had won five of those contests; Navy had won three times, and there was one tie.

9 Robert F. Kelley, “70,000 Watch Army Beat Navy, 6 to 0: Gate Over $600,000,” New York Times, December 14, 1930: S1.

10 1930 was the final season that legendary coach Knute Rockne coached at Notre Dame, leading them to an undefeated national championship. (Rockne was killed in a plane crash on March 31, 1931.)

11 “1930 Army Black Knights Roster,” found online at www.sports-reference.com/cfb/schools/army/1930-roster.html. Accessed July 2022. The 22 points allowed ranked third-fewest out of 106 college teams across the country. The 24.4 points scored per game was 15th-best in the country.

12 In the six games played from 1922 to 1927, Army had won four times; there were two ties. Coming into this game, Army held the series advantage with 15 wins against 12 losses (there had been three tie games as well).

13 Kelley.

14 Kelley.

15 Kelley.

16 Arthur J. Daley, “Navy Wig-Wag Talk Keeps Crowd Happy,” New York Times, December 14, 1930: S3.

17 Daley.

18 Team captain Humber played as a left guard for Army. In 1930 Humber received second-team All-America honors from the International News Service. See James L. Kilgallen, “All-American Team Selected,” Chester (Pennsylvania) Times, December 1, 1930: 15.

19 According to Perry Lewis of the Philadelphia Inquirer, Navy had not lost a coin toss all season.

20 Jimmy Powers, “Army Gets Navy Goat, 6-0,” New York Daily News, December 14, 1930: 86, 88.

21 Powers.

22 Allison Danzig, “Army-Navy Contest Described in Detail,” New York Times, December 14, 1930: S3.

23 Powers.

24 Powers.

25 Kelley.

26 Powers.

27 Associated Press, “Statistics Reveal Why Cadets Won,” San Bernardino County (California) Sun, December 14, 1930: 24.

28 Kelley.

29 “Major Sasse Pays Tribute to Cadets,” New York Times, December 14, 1930: S3.

30 “Major Sasse Pays Tribute to Cadets.”

31 “Navy Coach Proud of Middies’ Battle,” New York Times, December 14, 1930: S2.

32 Kelley.

33 “Army Eleven Defeats Navy, 6-0, Before 70,000; Jobless Fund Gets $600,000 From Stadium Game,” New York Times, December 14, 1930: 1.