August 31, 1932: Day of the Ineligible Player

This article was written by Lowell Blaisdell

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 25, 2005)

Well-seasoned SABR members will easily recall the days of perusing box scores in which frequently rather than rarely the lineups came to nine to a dozen players on each side. In nearly all instances, box scorekeeping was relatively easy. When now and then a box score addict encountered a batting order alteration caused by substitutions, a quick glance at the pinch-hitting notes, clarified how, when, and why this had occurred.1 For the aficionado, the symmetry, clarity, and certainty that he found in his daily ration of box scores provided a few moments of internal quiescence that seemed constantly to escape him in the otherwise unending turmoil of everyday living.

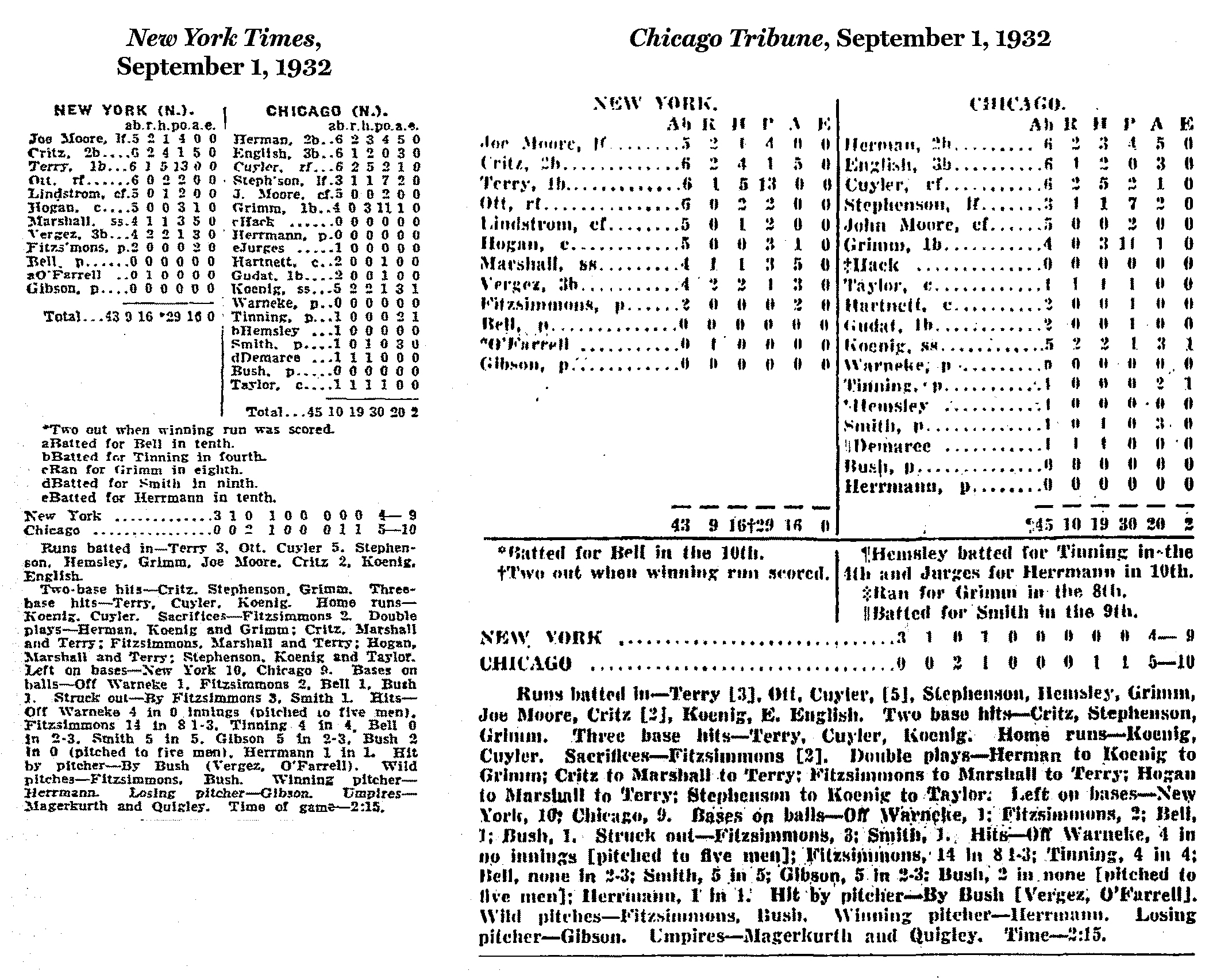

As an exception to this reassuring tableau, on August 31, 1932, the Chicago Cubs and New York Giants played a game at Wrigley Field that was extraordinary,2 ending in such a way as to cause two of the most influential newspapers, representing the cities of the rival teams—the Chicago Tribune and the New York Times—to print discrepant box scores.

In the game the Cubs gradually overcame a four run deficit, tying it in the ninth and winning it in the tenth. In the tenth inning, a unique batting order entanglement arose that created the newspapers’ box score asymmetry. The origins of this snarl began with two substitutions that Cub manager and first baseman Charlie Grimm made in the eighth inning. Having, as number six hitter, doubled, thereby narrowing the Giants lead to 5-4, he then withdrew for a pinch runner (Stan Hack). The number seven hitter, Gabby Hartnett, though a power at the plate, was slow, so Grimm had Marv Gudat, reserve outfielder and first baseman, bat for him.3 After Gudat made out, he stayed in the game as Grimm’s replacement at first base. Necessarily, he replaced Hartnett as the number seven hitter. Since there had to be another catcher, Zack Taylor replaced Hartnett, but equally unavoidably, as the number six, not number seven hitter.4

In the course of tying the game in the ninth, Frank Demaree, a reserve outfielder, pinch-hit for the relief pitcher, Bob Smith. This entailed no batting order repositioning, so the new Cub pitcher would continue to bat in the ninth spot.

During the Cubs ninth, it began to rain steadily. The umpires would have been justified in declaring the game ended in a 5-5 tie. However, since this was the Giants’ last game at Wrigley Field for the season, and it was important for the Cubs, they decided to allow it to continue. From then on, the steady rain had an important bearing on the outcome.

Grimm turned to Guy Bush, a starter, as his next relief pitcher. Unable to grip the wet ball properly, Bush gave up two hits, a walk, hit two batters, and made a wild pitch, while four Giant runs clattered in. Grimm had to replace him with his fifth pitcher, Leroy Herrmann, who had appeared in seven games that year and had a 6.39 ERA. Somehow Herrmann retired the side with no more runs scoring.

As the Cubs’ half of the tenth inning started, the rain began to beat down harder. Bill Terry, also a playing manager-first baseman, put in Sam Gibson—like Herrmann, barely a major leaguer—as his new pitcher. Up came the Cubs’ first hitter.

Several Cub players gathered around home plate umpire, George Magerkurth, to inform him that Bill Jurges, the injured regular shortstop, would pinch-hit for Leroy Herrmann. Grimm had gotten his number six and nine hitters mixed up. Since, according to the rule book, no manager on offense is permitted to replace a batter in a fixed batting position with a different player occupying another lineup spot, Jurges—whether Grimm or anybody else understood it or not—was pinch-hitting for Taylor, not Herrmann. It is not an umpire’s duty to inform a team that it is about to permit one of its players to bat out of turn, so Magerkurth listened without comment to what the Cubs had to say. The field announcer informed the fans that Jurges would bat for Herrmann.

Jurges made out. Neither before his at-bat nor especially after did the Giants file a protest, since his out had served their purpose. This effectively eliminated Taylor from the game. Gudat, the number seven hitter, easily made out also. The Giants had a four-run lead, there were two outs, and nobody on. How could they possibly lose?

Mark Koenig, the Cubs fill-in shortstop, came up. He drove a home run high into the right field bleachers. This made the score 9-6. Among the players and such rain-drenched fans as remained, this ignited a spark of hope.

Then came the most baffling development of this-or almost any other game. Who batted but Zack Taylor! By rule in the catcher’s number six spot, he turned up intending to bat ninth.

In the rule book for 1932, two provisions covered Taylor’s situation. First, rule 44, section 1—the usual batting out-of-turn provision—specified that a claim to its application had to be made before the first pitch to the next batter. Second, rule 17, section 2—which almost never was needed—held that any player replaced by another could not return to the game.5 At this moment Magerkurth should have ordered Taylor back to the bench as no longer eligible to play. That he did not suggests that in the rain and confusion, he too had gotten tangled up.

Taylor singled to right. All that Terry had to do to win the game then and there was, before the next pitch, to remind Magerkurth either that as an illegal batter, Taylor could not possibly be in the correct batting position, or, if Magerkurth’s omission had granted him a phantom batting status, then he was still batting out of order because the ninth spot belonged to Herrmann. Magerkurth then would have invoked the “out” penalty for a hitter batting out of turn, and the Giants would have won. In the moment while the great question hung in the rain, Taylor was a hitter who had not only batted out of turn, but was not even in the game, yet had delivered a vital hit.

Terry made no move. It is barely possible that, still enjoying a three-run lead with two out, he felt that it would come more easily through some routine play6 than to try, in the boggy bedlam, to get the umpire’s attention long enough to explain that the Giants had won for as sane a reason as that the rule book said so. Much more likely, however, is that between keeping up with his field position on the field and the chaos on the field, he had become hopelessly entangled in Grimm’s substitutions. After all, Grimm himself had. This episode graphically illustrated one reason why playing managers gradually became obsolete. In a sudden, in-game rules crisis a playing manager had too much to do to protect his team on rule book technicalities.

Gibson threw a pitch to the next batter, so Taylor’s hit stood. Furthermore, this legitimatized him as a batter hitting in the proper spot. As the game continued., it quickly took an ominous turn for the Giants. The next two batters singled, scoring Taylor and making it 9-7. Up came Kiki Cuyler, the Cubs fine right fielder and years later Hall of Fame electee. He was a valuable clutch hitter. In this game he already had four hits. One was a triple that hit the scoreboard then at ground level in deep center field-a deed accomplished only thrice before.7 Another was the two-out single in the ninth inning that had tied the score. Moreover, earlier in the summer, in a last of the ninth tie with Gibson pitching, he had singled to win the game.

Gibson pitched to him this time with it raining harder than ever, and almost unbelievably Cuyler slammed a home run into the bleachers just to the right of the scoreboard. It won the game for the Cubs, 10-9. Such fans as remained all but went berserk. Actually, given the conditions in which Cuyler hit this home run, it was a greater feat than Gabby Hartnett’s more famous “homer in the gloaming,” September 28, 1938.

From the team’s standpoint, this was the climactic end of a 12-game winning streak. So inspirational was the finish that it all but ensured that the Cubs would win the 1932 National League pennant. Of its kind, so a rare a feat was it that in more than 70 years since not once has the team won with a five-run rally in the last half of an extra-inning game.

To return to the Tribune’s and the Times’ disparate box synopses, suppose an ardent fan from each city had examined his newspaper’s box score and game account. What would he have found? Since the Cubs’ victory was a momentous one, the Windy City reader would have been able to pore over several columns devoted to the game, including an elaborate account of the tenth-inning fantasy. However, he would have had to end up shaking his head in disbelief at the Tribune’s version of the box score. If, as it insisted in its game account, Jurges had batted for Taylor in the sixth position—where its box listed him as playing then how could it account for the actual fact that the reserve catcher had batted ninth, without so indicating it? Furthermore, if, as the box conceded in its pinch-hitting footnotes, Jurges had batted for Herrmann, then how did this last pitcher turn up batting sixth, when the only ninth-inning change showed Demaree pinch-hitting for the pitcher, meaning that whoever was the final pitcher had to be batting ninth? There was no possible explanation of the discrepancies.

As for the Giants fan, he would at least have had before him what officially was the correct box score. However, he would have been at a loss to figure out how it possibly could be so. The Times account of the game was a lackluster one, so the fan would have obtained no enlightenment from that quarter. But the effect was to leave the fan mystified as to what occurred. This box score addict would have quickly spotted that the only Cub ninth-inning substitution was Demaree batting for the pitcher, meaning that any subsequent Cub pitcher was bound to bat ninth. Yet while Bush was listed in that spot, somehow Herrmann, his successor, appeared in the sixth spot. Furthermore, how could it be that catcher Taylor appeared as batting ninth when his predecessor, Hartnett, was shown as hitting seventh.8 Whether the box score fancier lived in Chicago or New York, he could only conclude in silent desperation that it was not even safe to assume infallibility in this one small corner of his life where he thought he had found it.

LOWELL BLAISDELL is Professor of History Emeritus at Texas Tech University. A lifelong Cub fan and SABR member for over 25 years, he has written articles on baseball’s past for The Baseball Research Journal, The National Pastime, and Baseball History.

Notes

- Soon after the end of World War II, the emergence and development of the defensive double switch put an end to easily figuring out how a change in the batting order had come to be. The author desires to express his gratitude to James Harper, a longtime friend, former academic colleague, and equally vociferous fan, for his valuable help as advisor, editor, and scribe.

- The Chicago Tribune noted the managers’ and umpires’ mistakes on September 1, 1932, in an article entitled: “Taylor Bats Out of Turn; Giants Umpires Miss It.” As if an omen, players and spectators alike were left agog by a full solar eclipse that occurred immediately prior to the

- In the third inning, a heavy shower had halted play for half an hour, making the infield soft, leading Grimm to feel that if Hartnett hit anything on the ground, he would be a sure out, while Gudat, who was quite fast, might beat out a slowly hit

- This and subsequent references to game happenings are drawn from the Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1932, from the Chicago Daily News’ “My Biggest Baseball Day” Series, 1940s by John P. Carmichael, which included Charley Grimm’s “Greatest Day;’ as recounted to Hal Totten, and, slightly, from the New York Times, September 1, 1932.

- The two rules from the 1932 rulebook are quoted in the Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1932. The author, who listened to the game on the radio as a 12-year-old, recalls that the broadcasters mentioned the batting out of order, but missed the other rule violation.

- This, at least, was what Grimm thought the Giants manager might have had in mind—”Grimm’s Biggest Baseball Day,”p. 15.

- Previously only Rogers Hornsby, while he was with the St. Louis Cardinals, and Hack Wilson had smashed drives far enough to hit the scoreboard on the fly. A month after Cuyler’s hit, Babe Ruth, with his most famous home run, cleared the scoreboard for the only time.

- Until recent decades it was the scoring custom, when a pinch-hitter stayed in the game, not to list him in the pinch-hitting notes. Ordinarily this made no difference except to leave a certain number of players’ pinch-hitting statistics in the record books as fewer than they actually were. However, in a very rare case such as this one wherein Gudat pinch-hit, followed by then staying in the game, produced a lineup alteration, the failure to identify him as a pinch-hitter meant that the Times box score left the problem of how the batting order switch had occurred entirely unexplained.