Babe Didrikson and Baseball

This article was written by Vince Guerrieri

This article was published in Spring 2022 Baseball Research Journal

For most of Babe Didrikson’s life, Major League Baseball was closed off to all but white men, but it was possible for African Americans and women to play professional baseball in other venues. Didrikson, technically the first woman to pitch for a major league team, even though she was unable to be signed, was able to partake in professional baseball at various stages in her career, less because of her athletic prowess (which was considerable, as evidenced in other sports) and more because her individual fame as one of the most significant sports figures of her era transcended barriers.

When “the little wild flower of the Lone Star State,”1 as writer Damon Runyon wrote, was in her prime, people ran out of superlatives to describe her. After watching her beat him on the golf course, legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice—himself a scratch golfer— said she was “without any question the athletic phenomenon of all time, man or woman.”2 He would be a friend and booster of hers for the rest of his life. “I once shook hands with Miss Didrikson,” recalled Ty Cobb in 1945. “A minute or so later I looked at my hand to see if it was still hanging on. It was, but I don’t think it has ever been the same.”3

Didrikson’s athletic career spanned her brief adult life, from the Olympics in 1932 to her premature death at age 45 from cancer in 1956. In that time, she was rarely out of the public eye. Even rarer, she was able to make a living as an athlete in a series of sports, including golf, basketball, pool, tennis and even baseball. She was an instant sensation when she arrived on the national scene, winning medals in all three events she competed in at the Los Angeles Olympics—impressive, considering there were only six women’s events at the games, and no woman could compete in more than three events! She would eventually be most noted— and compensated—for her golf career. She helped found the Ladies Professional Golf Association in 1949 and was initially the dominant player in wins and money. But baseball was the dominant sport of the era: it was nearly mandatory that the country’s top sportswoman try her hand on the diamond as well.

Mildred Didriksen (she changed the spelling of her name as an adult) was born on June 26, 1911, in Port Arthur, Texas, the sixth of seven children (five sons and two daughters) of Ole and Hannah Didriksen. Mildred, who never let the facts get in the way of a good story, said in her autobiography that her baseball prowess as a girl—including a game where she hit five home runs—led to her acquiring the nickname Babe, for Babe Ruth.4 But Don Van Natta’s biography Wonder Girl notes that her mother called her “Bebe” (“baby” in several European languages) as an infant, at the time when George Herman Ruth himself was acquiring the nickname as one of Jack Dunn’s babes with the minor league Baltimore Orioles.5

The Didriksens moved from Port Arthur inland to Beaumont when Mildred was a girl. Even as a child, Didrikson distinguished herself as an athlete, and demonstrated no interest in what were regarded as the feminine pursuits of the day. At Beaumont High School, she played basketball, volleyball, tennis, baseball, and golf and was on the swim team. She read stories of the 1928 Olympics and was determined to compete in the next one.6

Her athletic prowess attracted the attention of Melvorne McCombs. The Colonel, as he was known, was hired by Employers Casualty to manage the insurance company’s athletic department, overseeing a slate of teams in the days when many semi-pro teams had their basis in local businesses. Didrikson would play on the Employers’ women’s basketball team, known as the Dallas Golden Cyclones, and get $75 a month for a clerical job with the company. She also lobbied McCombs to revive the company’s track team, and then proceeded to set—and repeatedly break—records in the javelin throw, high jump, baseball throw, and hurdles. In the 1932 AAU championships, she competed in an unprecedented eight events, winning five and qualifying for the Olympics in three: high jump, javelin, and the 80-meter hurdles. She had won the meet for Employers Casualty as the sole member of the team.7

In the Olympics, Didrikson set a record in the javelin throw, set a record in and won the 80-meter hurdles by an eyelash, and got the silver medal in the high jump.8 Rice, who was covering the Olympics, invited her to play golf with him and three other sports-writers, Paul Gallico,9 Westbrook Pegler and Braven Dyer. On her first shot off a tee (Rice said he set up the tee for her; she was apparently prepared to hit off the turf, though she played golf in high school), she drove the ball an estimated 240 yards—a glimpse of her skill to come, and her oft-repeated motto on the links: “You’ve got to loosen your girdle and let it rip.”10

Didrikson returned home to Texas to a hero’s welcome, first in Dallas, the home of Employers Casualty, and then in her hometown of Beaumont. She was driving a new Dodge—evidence that she had received some recompense for her athletic prowess, the Amateur Athletic Union ruled, stripping her of her amateur status.

Undaunted, Didrikson rode the wave of popularity her Olympic medals gave her. She performed on the vaudeville circuit, playing harmonica, and played semi-pro basketball in the winter of 1933-34. Her basketball team, called Babe Didrikson’s All-Americans, included Jackie Mitchell, who’d gained a small measure of fame for striking out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in an exhibition game with the Chattanooga Lookouts.11

Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis reportedly took a dim view of the stunt, voiding Mitchell’s contract because he viewed baseball as too strenuous a sport to be undertaken by women.12

Following the basketball season, Didrikson went south for Major League Baseball spring training. (One wonders if her time with Mitchell was an influence.) She stopped first in Hot Springs, Arkansas, to sharpen her pitching skills under the tutelage of future Hall of Famer Burleigh Grimes at the Ray Doan Baseball School.13

From there, she headed south, to Florida. Doan touted her as the first woman to play for a major league team when she pitched for the Athletics in a spring training game against the Dodgers on March 20.14 The Dodgers, best known at the time for their ineptitude, hit into a triple play with Babe pitching, “which was at least a variation of their celebrated eccentricities,” wrote the next day’s Cleveland Plain Dealer. “There were no enemy fly balls thudding into Dodger skulls or members of the cast attempting to steal third with the bases populated.”15

But the next day against the Red Sox on March 22, it appeared she got found out. Pitching for the Cardinals against Boston, she gave up three runs in an inning’s work, after Max Bishop, who led off for the Red Sox, told his teammates, “Count ten before you swing. This girl does not throw as fast as she runs.” Cardinals manager Frank Frisch was content to play along at first, but then yanked her, saying after the game (which the Cardinals won), “A woman’s place is in or around the home. I was glad to give this dame a lift, but there’s such a thing as carrying a thing too far.”16

On March 25, she pitched for the Indians against their Double-A farm team, the New Orleans Pelicans, in New Orleans. “Babe Didrickson [sic], Texas’ renowned girl athlete, pitched two scoreless innings against the New Orleans Pelicans, smacked out two line drives, one fair and one foul, and looked as if she had been playing baseball in fast company all her life,” wrote Gordon Cobbledick in the next day’s Plain Dealer.

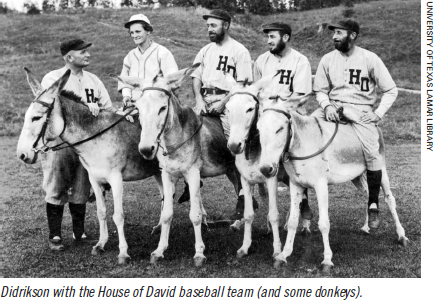

Following her time at spring training, Didrikson signed with the House of David barnstorming baseball team. The House of David was a religious order that had been formed early in the twentieth century in Benton Harbor, Michigan. It encouraged physical fitness—as well as celibacy—and many of the men who were part of the commune played baseball, leading to a traveling team, which also featured major league players in an effort to grab publicity, including at various points Chief Bender and Grover Cleveland Alexander. (Its promoter was Doan, he of the baseball school.) The order was also known for men wearing long hair and flowing beards, and in a game, a woman in the stands asked Didrikson where her whiskers were. The Babe’s riposte? “I’m sittin’ on ’em, sister, just like you are.”18

Didrikson spent a summer playing with the House of David—and was handsomely paid, making $1,500 a month. It was estimated that she’d made $25,000 in the two years following her Olympic performance.19 Employers Casualty would always take her back, but she wanted to make a living playing sports—and she couldn’t do it playing baseball. (Although at that point, many professional ballplayers had offseason jobs as well.20)

Didrikson turned to one of the few sports where women could regularly compete: golf. But at that point, amateurism was still embraced, to the point where the men’s golf’s Grand Slam was the US and British Opens and the US and British Amateurs.

Didrikson practiced incessantly, learning the game and its rules, and won the Texas Amateur. However, the United States Golf Association determined that Didrikson had played professional sports—even if not golf—and her amateur status was revoked. Of course, there were always the thoughts among the country club set that Didrikson was a woman, but she was not a lady. As a child, she had tomboy tendencies. As an adult, she seemed indifferent to marriage and motherhood, the two primary options for young women of the era.21

That changed when she met George Zaharias at a PGA Tour event. Didrikson had started touring, playing golf exhibitions with Gene Sarazen (whom she called Squire in front of adoring and amused crowds). And she and Zaharias, a professional wrestler known as the Crying Greek from Cripple Creek, hit it off. Didrikson had been feminizing her rough-hewn image to begin with, and she and Zaharias had become a couple.22 They married on December 23, 1938, at the St. Louis home of wrestling promoter Tom Packs. Several members of the Cardinals attended the ceremony, including Joe Medwick and Leo Durocher, who served as Zaharias’ best man. (Durocher’s wife at the time, the former Grace Dozier, was the matron of honor for Didrikson. A fashion designer, she also made Didrikson’s wedding outfit, a powder blue dress and blue hat.)23

Through her husband, she met Fred Corcoran, a sports impresario who helped put professional men’s and women’s golf on the map. Corcoran was hired in 1936 as the tournament manager for the PGA, at the time an organization that promoted a series of winter tournaments in warm-weather locales to keep club pros sharp in the offseason.

But he’d also served as an adviser to individual athletes—including the new Mrs. Zaharias. Then as now, baseball players liked spending their off time on the golf course, and Corcoran developed contacts there as well. He’d set up a series of exhibitions between Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb, both well into retirement from baseball,24 and was an unofficial agent for Ted Williams, having met the Splendid Splinter through his brother, who sold Williams a car.

Corcoran’s contacts in the world of baseball kept Babe Zaharias in and around ballparks and ballplayers. She’d tour ballparks regularly for exhibitions, taking a few cuts at the plate pregame and possibly pitching as well—maybe even hitting golf balls off home plate to try to clear the outfield fence.

In her autobiography, she recalled an exhibition at Yankee Stadium before a game. She showed off her golf prowess, then played third base during infield practice—and talked Joe DiMaggio into facing her at the plate.

I went over to the Yankee dugout to get him. “Come on, Joe,” I said. “I’m going to pitch to you.” He didn’t want to come, but I took him by the arm, and I grabbed a bat and handed it to him. I walked Joe out to home plate and bowed low.

All I was afraid of was that I might hit him with a pitch, or that he might hit me with a batted ball. ‘Whatever you do, please don’t line one back at me!’ I said to him just before I went to the mound. I did hit him right in the ribs with one pitch, although I don’t think it hurt him. But I guess he was being careful about his batting. He skied a few, and then finally he took a big swing and missed and sat down.25

Corcoran even got Didrikson to visit Williams in Florida, where they put on a hitting exhibition—golf balls, not baseballs. Williams outdrove her, but not by much, and once, when he hit a worm-burner off the tee, Didrikson joked, “Better run those grounders out, Ted! There may be an overthrow.”26

Ultimately, Didrikson continued to perform at exhibitions, but was able to regain her amateur golf status in 1943. (It was possible to do so with the USGA by not playing professionally for three years.) She then won 14 straight tournaments, but had her sights on bigger things.

In 1949, Didrikson, Corcoran and several other women golfers gathered to form the Ladies’ Professional Golf Association. Patty Berg was the inaugural president, and she was succeeded by Didrikson. For the tour’s first four years, Didrikson was also the leading money winner. Between golf and endorsements, Didrikson was making $100,000 a year.

She was the most famous woman athlete in the world, and in 1950 was named the Best Woman Athlete of the First Half of the 20th Century by the Associated Press, which would eventually name her female athlete of the year six times—five for golf and one after her Olympic performance in 1932.27

In May 1952, her hometown doctor, W.E. Tatum, performed surgery on Didrikson, repairing a strangulated femoral hernia. That fall, Didrikson started to tire in golf matches. She seemed sicker, her husband recalled, and was passing blood. But she deferred seeing a doctor, telling George, “Just let me get a good hot bath and a rubdown, and I’ll be ready to bust loose again in the morning.”

The following year, after winning her namesake tournament in her hometown of Beaumont, she eventually made it back to Dr. Tatum, who diagnosed her with colon cancer—and noted that her delay in visiting the doctor was a fateful one. “Well, that’s the rub of the greens,” she said laconically.28

Didrikson underwent surgery, including a colostomy. George Zaharias said she made sure her clubs were in her recovery room, saying, “I want to be able to see them every day because I’m going to use them again.”29

And she did. She was on the course competitively in 10 months, and won the 1954 Women’s US Open. Not only that, in an era where cancer was feared as a death sentence (and some patients weren’t even told they had cancer30), Didrikson became not just a visible high-profile patient, but one who was open about her diagnosis, urging others to get regular checkups. She made PSAs for cancer organizations and started her own foundation. And she visited children in cancer wards. “She gave people hope,” Patty Berg said.31

The following year, she underwent surgery for a ruptured disc, and doctors discovered the cancer had spread to her spine. There was no coming back this time, and early on September 27, 1956, Didrikson died.

Her career earnings on the LPGA Tour were $66,237, with wins in 72 tournaments.32 But that was an era when professional golfers—both male and female—used tournament wins as a selling point for endorsements, where the real money was. Beyond her pro golf career—her second act—she was hailed as one of the greatest female athletes ever, with skills in basketball, track and field and yes, baseball. At her funeral, the Rev. C. A. Woytek read “The Answer,” a poem written by Grantland Rice, who’d died two years earlier, writing up until the very end:

The loafer has no comeback and the

quitter no replyWhen the Anvil Chorus echoes, as it will,

against the sky;But there’s one quick answer ready

that will wrap them in a hood:Make good

VINCE GUERRIERI is a journalist and author in the Cleveland area. He’s the secretary/treasurer of the Jack Graney SABR Chapter. He has written about baseball history for a variety of publications, including Ohio Magazine, Cleveland Magazine, Belt Magazine, and Deadspin, and League Park is his happy place. He can be reached at vaguerrieri@gmail.com, or found on Twitter @vinceguerrieri.

Notes

1. Damon Runyon, “Two Straight World Marks Fall for Babe,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 4, 1932, 16.

2. “Personal Glimpses: The World-Beating Girl Viking of Texas,” Literary Digest, August 27, 1932, 26.

3. “Take a Quote, Please,” Yank Magazine, February 16, 1945.

4. Babe Didrikson Zaharias, as told to Harry Paxton, This Life I’ve Led (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co, 1953) 11.

5. Don Van Natta Jr., Wonder Girl (New York: Little, Brown & Co, 2011) 20. Didrikson also gave her birthdate variously as 1913 or 1914, which makes her story about being nicknamed for Babe Ruth as a girl slightly more plausible. This Life I’ve Led, 28.

6. Larry Schwartz, “Didrikson was a woman ahead of her time,” ESPN.com. https://www.espn.com/sportscentury/features/00014147.html.

7. Didrikson won the hurdles in a judgment call against Evelyne Hall in what seemed to be a photo finish. In a balancing of the cosmic scales, judges’ ruling that she had fouled on her jump gave her the silver instead of the gold. Van Natta, 105-12.

8. Didrikson won the hurdles in a judgment call against Evelyne Hall in what seemed to be a photo finish. In a balancing of the cosmic scales, judges’ ruling that she had fouled on her jump gave her the silver instead of the gold. Van Natta 105-12

9. Gallico, better known for his fiction, including the novel The Poseidon Adventure, wrote an article about Didrikson calling her a “muscle moll,” offering descriptions of her as mannish and contributing to rumors about her sexuality that dogged her all her life and persisted after her death. Van Natta, 140-45.

10. Larry Schwartz, “Didrikson was a woman ahead of her time,” ESPN.com. https://www.espn.com/sportscentury/features/00014147.html.

11. Tony Horwitz, “The Woman Who (Maybe) Struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig,” Smithsonian. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-woman-who-maybe-struck-out-babe-ruth-and-lou-gehrig-4759182.

12. Horwitz, “The Woman Who (Maybe) Struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.”

13. “Didrikson is baseball ace,” The Amarillo (Texas) Globe-Times, March 14, 1934, 11.

14. Associated Press story, quoted by J.G. Preston, “Babe Didrikson in baseball spring training 1934,” https://prestonjg.wordpress.com/2013/08/11/babe-didrikson-in-baseball-spring-training-1934.

15. “Didrikson Throws Those Funny Men Triple Play Ball,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 21, 1934, 17.

16. John Lardner, “Ungallant Red Sox Show Up Babe,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 27, 1934, 20.

17. Gordon Cobbledick, “Johnson Leads Rally as Indians Win Two Games,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 26, 1934, 17.

18. Ann Dingus, “Babe Didrikson,” Texas Monthly, June 1997. https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/babedidrikson/.

19. Van Natta, 159.

20. “When the Offseason meant Job Season,” Baseballhall.org, recovered Feb. 21, 2022. https://web.archive.org/web/20150227081913, http://baseballhall.org/discover/when-the-offseason-meant-job-season.

21. Michael Beschloss, “A Maverick’s struggles in a more conformist time,” The New York Times, August 9, 2014.

22. Beschloss, “A Maverick…”

23. This Life I’ve Led, 112-13.

24. Ruth referred to the matches as “The Left-Handed Has-Beens Golf Championship of Nowhere in Particular.” John H. Schwarz, “Fred Corcoran, Mr. Golf’s Turn at Bat,” Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2021.

25. This Life I’ve Led, 181.

26. This Life I’ve Led, 182.

27. Schwartz, “Didrikson was a woman ahead of her time.”

28. George Zaharias, as told to John M. Ross, “The Babe’s Last Battle,” American Weekly, 4.

29. “The Babe’s Last Battle.”

30. A 1953 survey of Philadelphia physicians indicated that 69 percent of respondents said they didn’t advise cancer patients of their diagnosis. Cited in “How the doctor’s nose has shortened over time; a historical overview of the truth-telling debate in the doctor-patient relationship,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, December 2006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1676322.

31. Van Natta, 315.

32. LPGA website, “Career Money,” accessed March 27, 2022: https://www.lpga.com/statistics/money/careermoney.