Babe Ruth and Baseball Diplomacy

This article was written by Rob Fitts

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

The American ambassador to Japan stretched out his long legs and put the final touches on the speech to welcome the All American baseball team to the Land of the Rising Sun. Although the ambassador, Joseph Grew, was probably pleased with it, it read like most of his speeches – banal and pompous. “I am a ‘fan’ myself, decidedly so, and you may be sure that it is to me a great privilege, and it gives me one of those good old-time thrills that I used to get in exuberant youth, to find myself on the same platform with some of the doughty warriors whose names and valiant achievements have been just as familiar as those of the old Greek heroes of whom I learned at school but who could never quite compete in my youthful estimation with our own heroes of the diamond.” At least it was short and ended with an appropriate message of goodwill. “I am confident that the result of your visit here will be a further contribution to the ideal of mutual understanding, mutual respect, and mutual friendship between our two countries…”1

In November 1934 Japanese-American mutual understanding, respect, and friendship needed a boost. The two nations were slipping toward war as they vied for control over China and naval supremacy in the Pacific. Politically, Japan was in turmoil. The Japanese had enjoyed a form of democracy and rapid modernization under the rule of the Meiji and Taisho emperors. Yet, as Japan’s power grew, so did its nationalism. A growing minority felt that Japan should take its place among the world powers by expanding its military and colonizing its neighbors. Ultranationalist societies began assassinating liberal politicians and members of the free press. By the early 1930s, the civilian government could no longer control elements of the military. In 1931 nationalistic officers engineered the invasion of Manchuria and twice plotted to overthrow the government. Japan had recently withdrawn from the League of Nations and was now threatening to withdraw from the Washington Naval Treaty, which limited the size of the major powers’ navies. War between the United States and Japan seemed inevitable.

On November 2 thousands of flag-waving, screaming fans lined the piers of Yokohama to welcome the All Americans to Japan. The team was one of the greatest squads ever assembled –Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Connie Mack, Jimmie Foxx, Earl Averill, Charlie Gehringer, Lefty Gomez, Lefty O’Doul, and a gaggle of lesser-known stars, including a journeyman catcher named Moe Berg, who would eventually become an operative for the OSS, the forerunner of the CIA. After ceremonies and interviews, a train whisked the players to Tokyo for what a reporter called “the wildest motor parade in history.”2

Hundreds of thousands packed the sidewalks, spilling into the streets, blocking traffic and trolleys. “Banzai! Banzai Babe Ruth!” they screamed. Reveling in the attention, the Bambino grabbed American and Japanese flags from the crowd and waved one in each hand as he stood in the rear of the limousine. Confetti and streamers showered the procession. Finally, the crowd surged forward, breaking police lines. They ran to Ruth, surrounding the limousine, climbing the bumpers, eager to touch. Ruth grinned, gave another hefty banzai and shook the outstretched hands – thousands of them.

“Tokyo Gives Ruth Royal Welcome,” blared the New York Times on November 3. The Associated Press article, picked up by newspapers across the globe, continued, “The Babe’s big bulk today blotted out such unimportant things as international squabbles over oil and navies.” Many observers considered the all-stars’ joyous reception proof that the two countries’ differences could be reconciled.3

The 1934 tour, however, began not as a diplomatic mission but as a publicity stunt to attract readers to the Yomiuri Shimbun. Owner Matsutaro Shoriki believed he could increase sales by sponsoring a team of major-league all-stars and covering the event in his newspaper. Realizing the tour’s potential to improve relations, both the governments of the United States and Japan quickly backed the idea.

The American players understood the importance of the trip. The night before the All Americans departed for Japan, Connie Mack called a meeting in his Vancouver hotel room. In a quiet, serious voice, the Philadelphia Athletics owner-manager explained that during this trip they would be more than baseball players, they would be ambassadors. Their behavior, both on and off the field, would reflect not only on themselves, but on major-league baseball and their country. Every player must promise to always try his best; to be friendly and sincere toward the tour hosts; to teach the Japanese players; and to be nice to the fans and always be respectful. “If you cannot keep this promise,” Mack continued, “please leave this room and you can go wherever you want.” Nobody stirred. Ruth, sitting in the front row, raised his right hand and swore that he would follow the rules. The others followed.4

The tour began with two games at Tokyo’s Meiji Jingu Stadium, where thousands camped overnight to secure the best general-admission seats. It soon became apparent that the fans had not come to root on their countrymen but to see the major leaguers, and especially the Babe, hit home runs. The crowd followed the Babe’s every move. A reporter stated, “[T]he fans went crazy each time Ruth did anything – smiled, sneezed, or dropped a ball.” One old man brought a pair of high-powered binoculars, amusing himself and neighboring fans by focusing on the Bambino’s famous broad nose, making his nostrils fill the lens.5

Another fan had a novel plan. He worked in a textile factory designing kimono and undergarment patterns. He would sit as close as possible to the field and study the Bambino’s face. He would memorize every feature, every wrinkle. Then, he would return to the factory and create a pattern of the Babe’s face for a new line of Babe Ruth underwear. He would become rich, he was certain.6

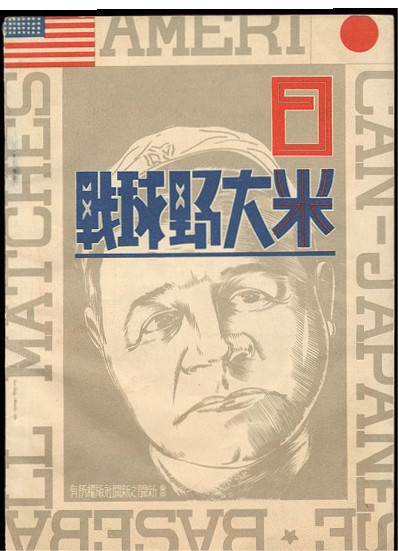

The 32-page program from the 1934 tour of Japan. (Courtesy of Robert Edward Auctions.)

Over the next four weeks, the All Americans played 18 exhibition games against a Japanese all-star team called All Nippon. They visited the northern cities of Sendai and Hakodate in Hokkaido; the industrial cities of Yokohama, Nagoya, and Osaka; the ancient capital of Kyoto; Kokura on the southern island of Kyushu; and, of course, Tokyo.

More than 450,000 people attended the games and hundreds of thousands more waited outside ballparks and hotels just to glimpse the major leaguers. The young All Nippon team was usually no match for the All Americans. The Americans swept the Japanese by a combined score of 181 to 36. But in two games, they came close to toppling the mighty major leaguers. On November 20 in the small town of Shizuoka at the base of Mount Fuji, 17-year-old Eiji Sawamura recorded 11 straight outs, including consecutive strikeouts of Gehringer, Ruth, Gehrig, and Foxx, before the Bambino broke up his no-hitter. The shutout continued until Gehrig homered in the seventh to give the Americans a 1-0 victory. The game would make Sawamura a national hero, and today the annual award for the best pitcher is named in his honor. In the following contest, the Japanese once again nearly upset the Americans, entering the bottom of the eighth with a 5-3 lead before several poor decisions by the Japanese manager cost them the game.

Everywhere, Ruth was the center of attention. His face dominated the tour’s advertising poster, the cover of magazines, newspapers, and baseball cards produced especially for the series.

The Babe’s major-league career was nearly over. His knees were shot, he had put on weight, and had hit .288 with 22 home runs during the ’34 season – his lowest batting average since 1916 and his fewest home runs since 1918. Before leaving the United States, he had agreed to part ways with the Yankees. But the Japanese fans’ enthusiasm made him feel like a young man. His bat responded as he led the tournament in batting average, home runs, RBIs, and runs scored.

The Japanese besieged the Bambino for autographs. A reporter noted that he “autographed everything held before him, hundreds of baseballs, handkerchiefs, menus, plain sheets of paper, hats, caps, neckties, shirts, every conceivable article thrust at him in feverish excitement.”7 Ruth told Ambassador Grew that he signed between four dozen and five dozen balls each day while in Japan. In the beginning, he responded to all salutations with the only Japanese word he knew, “Banzai!”8

During the games, the Babe clowned around. When playing first base, he would stand on the bag and then pantomime the height difference between the smaller Japanese runners and himself. The fans loved it. When he missed a pitch during batting practice, he would twist around in a circle and sometimes fall over to get a laugh. In the second game, after his fly ball was caught against the wall, he looked up at the disappointed crowd, “pointed his finger up into the air [to show] that the ball was too high, wrung his hands to show his disappointment that it wasn’t a homer” as the fans “roared” with laughter.9

Perhaps the highlight of the Bambino’s showboating came on a rainy day in the southern city of Kokura. The rain had turned the field to mud, prompting Ruth and others to play in rubber boots. At one point, the Babe borrowed an umbrella from a fan and huddled under it while playing first base. Few, however, know of the other interesting event that occurred during the game. In the fifth inning, with the bases loaded, a 3-and-0 count, and 5-foot-1, 116–pound Shinji Hamazaki on the mound, the Babe stepped out of the batter’s box and pointed to the outfield bleachers. Unlike his famed 1932 Called Shot, there was no doubt about Ruth’s intentions this time. Sure enough, the Sultan of Swat crushed the next pitch over the right-field wall and onto the roof of an adjacent building, shattering its clay roofing tiles.10

Between the games, the All Americans attended banquets, visited cultural sites, and made public appearances. Nearly all the events emphasized the countries’ mutual bond of baseball. Ruth became the team’s spokesman, spreading messages of international tolerance and goodwill. Grew noted in his diary, “[A]ll Japan has gone wild over him. He is a great deal more effective Ambassador than I could ever be.”11

On December 2 thousands of flag-waving fans crowded on to the train platform at Tokyo’s Ueno Station to say adieu. “Goodbye, Goodbye!” they shouted as Ruth sniffled and yelled “Sayonara, Sayonara! Banzai Japan!” As the train readied for departure, the crowd quieted to hear the Babe’s final speech, “I don’t know how to show my appreciation, but if I have a chance I will come back,” he concluded.12 The train took the players to Kobe, where they boarded the Empress of Canada for the homeward journey.

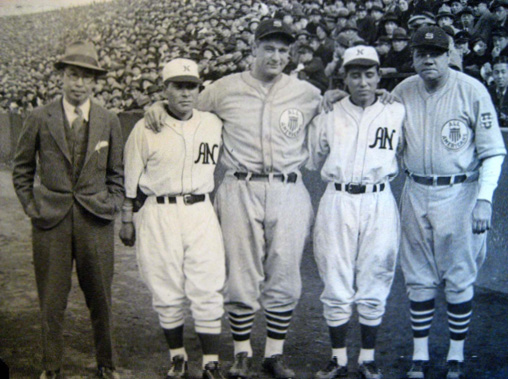

Sotaro Suzuki, an unidentified All Nippon player, Lou Gehrig, Hisanori Karuta, and Babe Ruth. (Courtesy of Yoko Suzuki.)

Many on both sides of the Pacific declared the tour a diplomatic coup. Connie Mack summed up the consensus that the trip did “more for the better understanding between Japanese and Americans than all the diplomatic exchanges ever accomplished.”13 Similar claims of baseball’s social importance had been around the game even longer than Mack. Nineteenth-century proponents endowed baseball with the almost supernatural abilities to indoctrinate the values of democracy, “civilize savages,” and even initiate world peace.14 By the 1930s, however, a more modest goal for international baseball emerged – mutual respect and friendship.

Initially, the 1934 trip seemed to accomplish these objectives. The intense Stateside media coverage allowed millions of fans in the United States to view the Japanese through the All American players’ eyes. Newspapers, magazines, newsreels, and radio reports depicted thousands of Japanese waving the American flag and cheering wildly for Babe Ruth and other American heroes. Americans heard the ballplayers’ glowing descriptions of Japan and its friendly inhabitants. The Chicago Tribune summarized, “Reports from Japan … reveal the Japanese people in an animated state of great good will toward the United States.”15 These reports were the most favorable press the Japanese had received for some time.

Many news stories focused on the Babe’s extraordinary success as a diplomat. “Babe, the Ambassador – Ruth Makes Japan Go American,” proclaimed The Sporting News. It continued, “The stars and stripes have not been much in evidence in Japan within recent years, because of various diplomatic and political aspects, but Babe Ruth, by one visit to Nippon has changed all of that, for the Ginza – Tokyo’s Broadway – broke out with a rash of Red, White, and Blue when the Bambino and his American League Stars came to town. … We believe that the recent trip to the Orient of baseball’s finest has served to delay, if not prevent, any possible conflict. We like to believe that countries having such a common interest in a great sport would rather fight it out on the diamond than on the battle field.”16

Ambassador Grew wrote, “their visit to Japan has been an unqualified success. … I told Babe Ruth that while he was here, there were two American Ambassadors to Japan, he and I. Certainly he and Connie Mack and the rest of the team did an immense amount of good towards the development of Japanese-American friendship … at least among certain sections of the people.”17

Unfortunately, it was the other portion of the Japanese population that would be the problem.

On the morning of February 22, 1935, when Yomiuri owner Matsutaro Shoriki arrived at work, Katsusuke Nagasaki was waiting. Nicknamed “The Newspaper Thug,” Nagasaki served as enforcer for the ultra-rightwing War Gods Society. As Shoriki began to climb the stairs into the building, Nagasaki strode forward, pulled a short samurai sword from beneath his coat, and swung for the neck. Fortunately, his aim was off and rather than decapitating the newspaperman, Shoriki fell forward with a large gash in the back of his head. He would survive. Later that day, Nagasaki walked into a local police station and gave a detailed confession. The primary reason for the assassination: Shoriki had defiled the memory of the Meiji Emperor by allowing Babe Ruth and his team of American all-stars to play in the stadium named in the ruler’s honor.18

In July 1937 Japan invaded China. Whatever hope there had been for reconciling the United States and Japan vanished. Ultimately, the two countries’ love for baseball could not overcome Japan’s desire for regional dominance.

The Babe was lounging in his Manhattan apartment when he learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor. For him, Pearl Harbor was a personal betrayal. Cursing the double-crossing SOBs, he heaved open the living room window that looked out over Riverside Drive to the Hudson River. His wife, Claire, had decorated the room with souvenirs from the Asian tour – porcelain vases and plates, exquisite dolls, and various sundries. The Babe stormed to the mantle, grabbed a vase and tossed it out the window. It crashed on the street below. Other souvenirs followed as Ruth kept up a tirade about the Japanese. Claire rushed around the room, gathering up the most valuable items before they joined the pile on Riverside Drive.19

The Sultan of Swat knew how to take revenge. Using the same charisma that made him an idol in Japan, he threw himself into the war effort, raising money to defeat the Japanese and their allies. One of Ruth’s many biographers noted, “Ruth in his late forties had become a patriotic symbol, ranking not far below the flag and the bald eagle.”20 But Ruth’s role as a symbol was not limited to the United States. In Japan, the jovial, overweight, self-indulgent demigod of baseball, so welcomed in 1934, had become a symbol of American decadence. On March 3, 1944, the New York Times published a description of Japanese infantry screaming, “To hell with Babe Ruth!” as they charged to their deaths in the South Pacific. The Babe’s response was classic Ruth, “I hope every Jap that mentions my name gets shot – and to hell with all Japs anyway!” The day after the Times article, Ruth took to the streets to raise money for the Red Cross, telling reporters that he was spurred on by the Japanese war cry.21

By the time of his death in 1948, Ruth and the Japanese had reconciled. Faced with the daunting task of reuniting the nations after World War II, the American occupying forces emphasized the countries’ shared love of baseball. On April 27, 1947, the Japan Pro Baseball League joined major-league baseball in celebrating Babe Ruth Day. Over the following decades, Ruth was immortalized with statues and plaques, as well as baseball cards, biographies, and magazines. Each year, hundreds of Japanese make the pilgrimage to the Babe Ruth Museum in Baltimore. Even today, more than eight decades after his visit to the Land of the Rising Sun, the Babe remains a symbol of the game that binds our two nations together.

A former archaeologist with a Ph.D. from Brown University, ROBERT K. FITTS left academics behind to follow his passion: Japanese Baseball. His articles have appeared in numerous magazines and websites, including Nine, the Baseball Research Journal, the National Pastime, Sports Collectors Digest, and on MLB. com. He is the author of five books on Japanese baseball: Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer (University of Nebraska Press, 2015); Banzai Babe Ruth (University of Nebraska Press, 2012); Wally Yonamine: The Man Who Changed Japanese Baseball (University of Nebraska Press, 2008); and Remembering Japanese Baseball: An Oral History of the Game (Southern Illinois University Press, 2005). Fitts is the founder of SABR’s Asian Baseball Committee and recipient of the society’s 2013 Seymour Medal, 2019 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award, 2012 Doug Pappas Award, and the 2006 Sporting News-SABR Research Award. He has also been a finalist for the Casey Award and a silver medalist at the Independent Publish Book Awards. His next book, Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese American Ballplayers will be published by the University of Nebraska in 2020.

Notes

1 Joseph Grew, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Joseph Grew Diaries and Scrapbook, 948-49.

2 Cleveland Press, November 23, 1934: 44.

3 New York Times, November 3, 1934: 2.

4 Sotaro Suzuki, Unofficial History of Japanese Professional Baseball (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 1976), 180-81.

5 Yakyukai 25 (no 3), 1935, 184.

6 Yomiuri Shimbun, November 6, 1934: 6.

7 Cleveland Press, November 23, 1934: 44.

8 Joseph Grew, Diaries and Scrapbook, November 16, 1934, 2122.

9 Japan Times, November 6, 1934, 6.

10 Osamu Mihara, My Baseball Life (Tokyo: Toshuppan, 1947).

11 Joseph Grew, Diaries and Scrapbook, November 6, 1934.

12 Yomiuri Shimbun, December 2, 1934.

13 The Sporting News, January 17, 1935: 4.

14 Robert Elias, The Empire Strikes Out (New York: New Press, 2000), 21-22.

15 Chicago Tribune, November 12, 1934: 14.

16 The Sporting News, January 3, 1935: 4.

17 Joseph Grew to Kenesaw Mountain Landis, Grew Diaries and Scrapbook.

18 Robert Fitts, Banzai Babe Ruth (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 235-39.

19 Julia Ruth Stevens, telephone interview with author, November 7, 2007.

20 Marshall Smelser, The Life That Ruth Built (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1975), 526.

21 New York Times, March 3, 1944: 2; March 5, 1944: 37.