Babe Ruth Dethroned? Whither the Sultan of Swat?

This article was written by Gabriel Costa

This article was published in 2002 Baseball Research Journal

During the first two decades of the 20th century, “inside baseball” dominated the way the national pastime was played. Superstars like Detroit’s Ty Cobb and Pittsburgh’s Honus Wagner, along with manager John McGraw of the New York Giants, were proponents of this style of baseball.

After Wagner and Cobb retired, many baseball experts believed that one or the other ranked as the greatest baseball player ever. This “consensus” lasted through the 1930s and beyond, even though the towering figure of Babe Ruth had played the game in an unparalleled way.

George Herman Ruth … known as the Babe … the Bam … the King of Swing … the Sultan of Swat.

But was he really the Sultan of Swat? Was he the best or merely one of the best?

Babe Ruth died in 1948. Opinions vary as to where he ranked with respect to the great players of all time.

But there was no real methodology to measure these until the field of sabermetrics was introduced. Bill James (See Tables 1 and 2) using such concepts as Runs Created and Win Shares, and John Thorn and Pete Palmer (See Table 3) with their Linear Weights method, concluded that Babe Ruth was the greatest player ever.

These arguments, and many others, were overwhelmingly in favor of Ruth. So much so that it was noted if a study ever found that Babe Ruth did not rank as the greatest player ever, there was something wrong with the analysis.

The Babe eclipsed Cobb and Wagner; McGraw’s “inside baseball” was forever eradicated. Since 1918 Babe Ruth was doing the unthinkable: he was posting seasonal home run totals that were greater than totals amassed by other teams. Year after year, Ruth slugged so many home runs that in his career he “outhomered” rival clubs 90 times.

And that was not all. Besides the homers, there were other unbelievable records: marks involving walks, runs scored, total bases, slugging percentage, and home run percentage. No one was close. There were many kings, if you will, but only one Sultan.

In addition to Ruth’s slugging, he was a great pitcher for the Boston Red Sox. In 1916 he led the American League with an earned run average of 1.75, had the lowest batting average allowed to opposing batters with .201, and established the league record for shutouts by a left hander with nine (since tied). He won 20-plus games twice, and never suffered a losing season, boasting winning percentages that never dipped below .640. His lifetime ERA was 2.28. Including a 5-0 record with the Yankees, Ruth ended up with career totals of 94 wins and 46 losses.

The Bambino pitched 29 1/2 consecutive scoreless innings in World Series play, a record that would stand for over four decades. Ruth was prouder of his pitching achievement than any of his slugging marks. His lifetime won-loss record was 3-0 in Series play with an earned run average of 0.87.

His World Series batting performances speak for themselves.

In 1919 when he set the major league record for home runs with 29, he led all American League outfielders with a fielding percentage of .996. He also spent enough time on the mound to hurl his team to nine victories.

Ruth stole more than 100 bases in his career, including 10 swipes of home.

No one was close to him, as a hitter or as an all around performer. It seemed that he should play in a higher league.

Babe Ruth’s career lasted for 22 years. When he retired in 1935, he owned scores of records and was responsible for many “mosts” and “firsts.” Some of these were:

- Most home runs in a season (60)

- Most lifetime home runs (714)

- Most lifetime runs batted in (2,211)

- Most lifetime walks (2,062)

- Most walks in a season (170)

- Highest slugging percentage in a season (.847)

- Highest lifetime home run percentage (8.5%)

- Most 50-plus home run seasons (4)

- First player to hit 30, 40, 50 home runs in a season (1920)

- First player to hit 60 home runs in a season (1927)

- First player to hit a home run in Yankee Stadium (1923)

- First player to hit an All-Star Game home run (1933)

He left behind quite a legacy of seemingly unbreakable records.

Then 1961 came along. Thirteen years after the Babe’s death, Yankee right fielder Roger Maris hit 61 home runs in an unbelievable whirlwind season. Ruth’s magic 60 had been toppled! His most famous seasonal record was now erased. The baseball world was stunned.

In the same year, Yankee ace Whitey Ford broke Ruth’s most cherished record. The southpaw pitched the last parts of 32 consecutive scoreless innings in World Series play. Ford added one more inning to his streak in 1962.

But the mammoth record of 714 lifetime home runs remained. It was doubtful that this monumental mark would ever be approached.

Ever so slowly, however, the figure of 714 was being approached. Outfielder Henry Aaron of the Braves, a model of consistency, was nearing the ultimate record. In 1974 Bad Henry smashed number 715, and added another forty homers before he retired. Another assault on the Sultan of Swat.

Then came the 1990s when home run totals seemed to grow at an exponential rate. Detroit outfielder Cecil Fielder hit 51 home runs at the beginning of the decade. He became the first player to break the 50-plus barrier since 1977 when Cincinnati Reds outfielder George Foster blasted 52 homers.

Five years later in 1995, slugger Albert Belle hit 50 home runs. This signaled the beginning of an onslaught of 50-plus home run seasons that has not stopped: from 1996 through 2002, no fewer than 17 times has the half-century mark been surpassed. The 60-plus barrier has been reached six times, three times by Chicago Cub outfielder Sammy Sosa.

In 1998 Mark McGwire of the Cardinals hit 70 home runs, marking the first time that total had been reached. Big Mac, recently retired, now holds the lifetime record for home run percentage.

In 2001, Giants outfielder Barry Bonds posted one of the greatest seasons ever, setting major league seasonal records for home runs (73), walks (177), slugging percentage (.863), and home run percentage (15.3%). A year later, Bonds posted the highest on base-plus-slugging mark ever (1.381).

Also in 2001, much traveled outfielder Rickey Henderson broke Babe Ruth’s career record for walks. One by one, Ruth’s records were falling. Was he still the Sultan of Swat?

The recent home run explosion has provided an impetus to reevaluate the once (still?) exalted position of the Bambino.

As mentioned above, Ruth outhomered teams 90 times, 14 in 1920 and 12 in 1927. It is unthinkable to envision any recent slugger rivaling this kind of dominance. McGwire, Sosa, or Bonds would have to hit in the neighborhood of 200 homers to surpass another team’s home run total.

Regarding the 50-plus home run barrier, it used to be just that: a barrier, something rarely scaled before the 1990s. But by the end of the 2002 season, the mark was equaled or surpassed 34 times, by more than 20 different players.

The increased frequency of such seasons, coupled with the preponderance of home runs, however, seems to suggest that a certain degree of difficulty with regard to hitting home runs has varied over the 82 years in question.

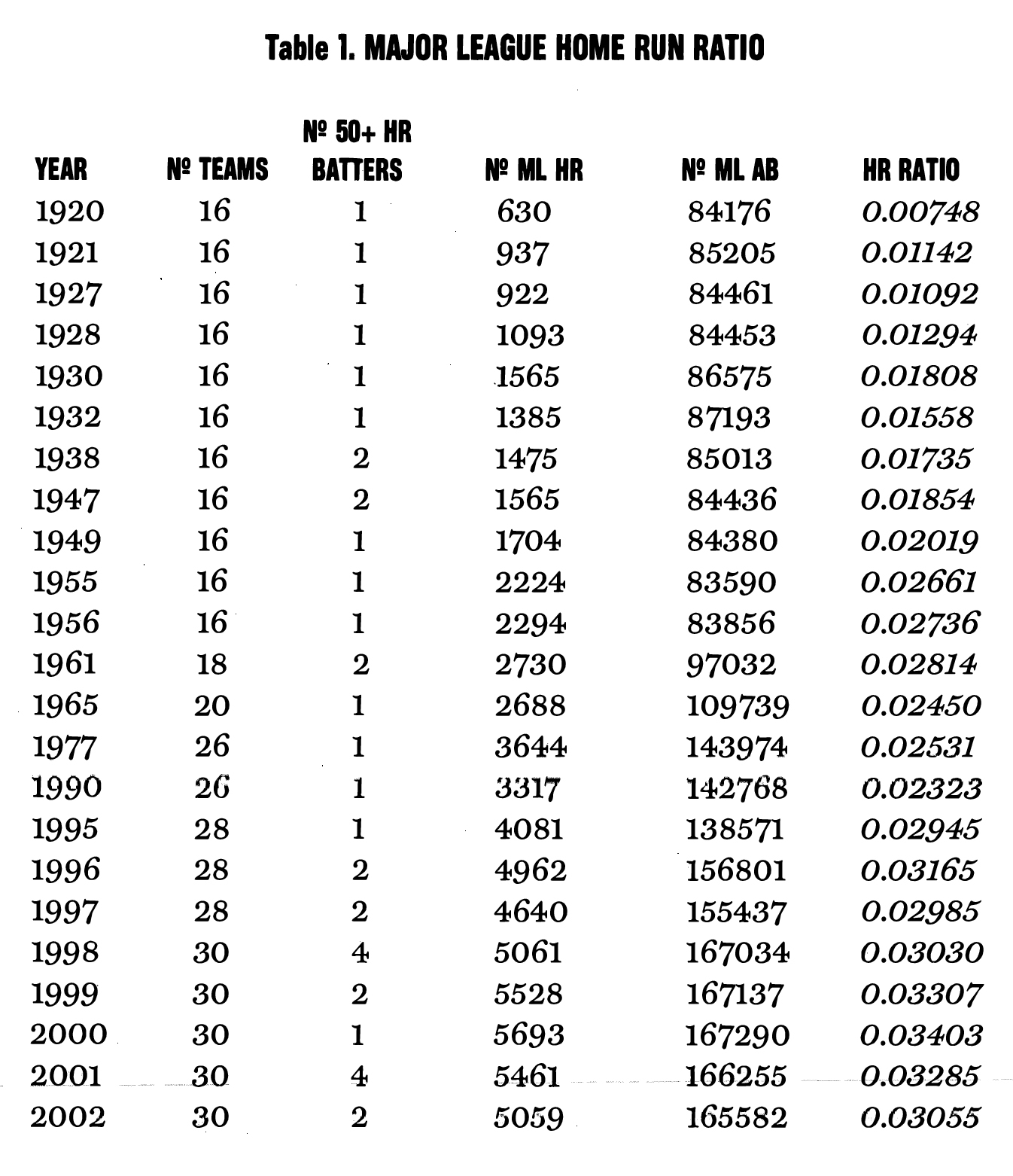

For example, in 1920 there were 630 home runs hit in 84,176 at-bats (there were 16 major league teams in that year). This gives an average home run ratio of 0.0074 home runs per at-bat. In 2001, by way of comparison, the 30 major league teams hit 5,461 home runs in 166,255 at-bats, giving a home run ratio of 0.03285. What does this mean?

Roughly speaking, this last statistic can be interpreted as meaning that the “average 2001 player” hit about 3.285 home runs per 100 at-bats, which is about 4.39 times greater than the 1920 figure. (See Table 1, which gives the major league home run ratio for each 50-plus home run season).

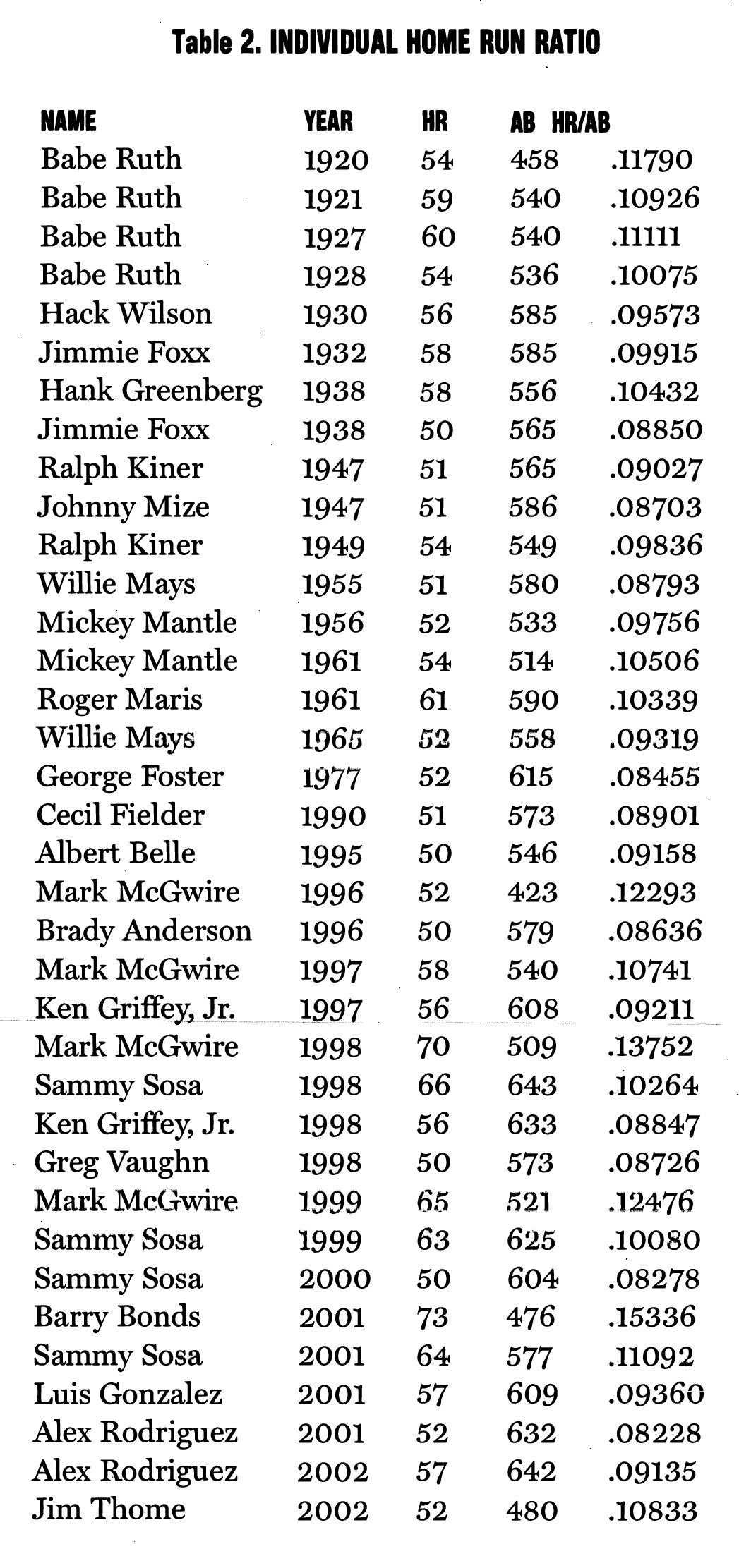

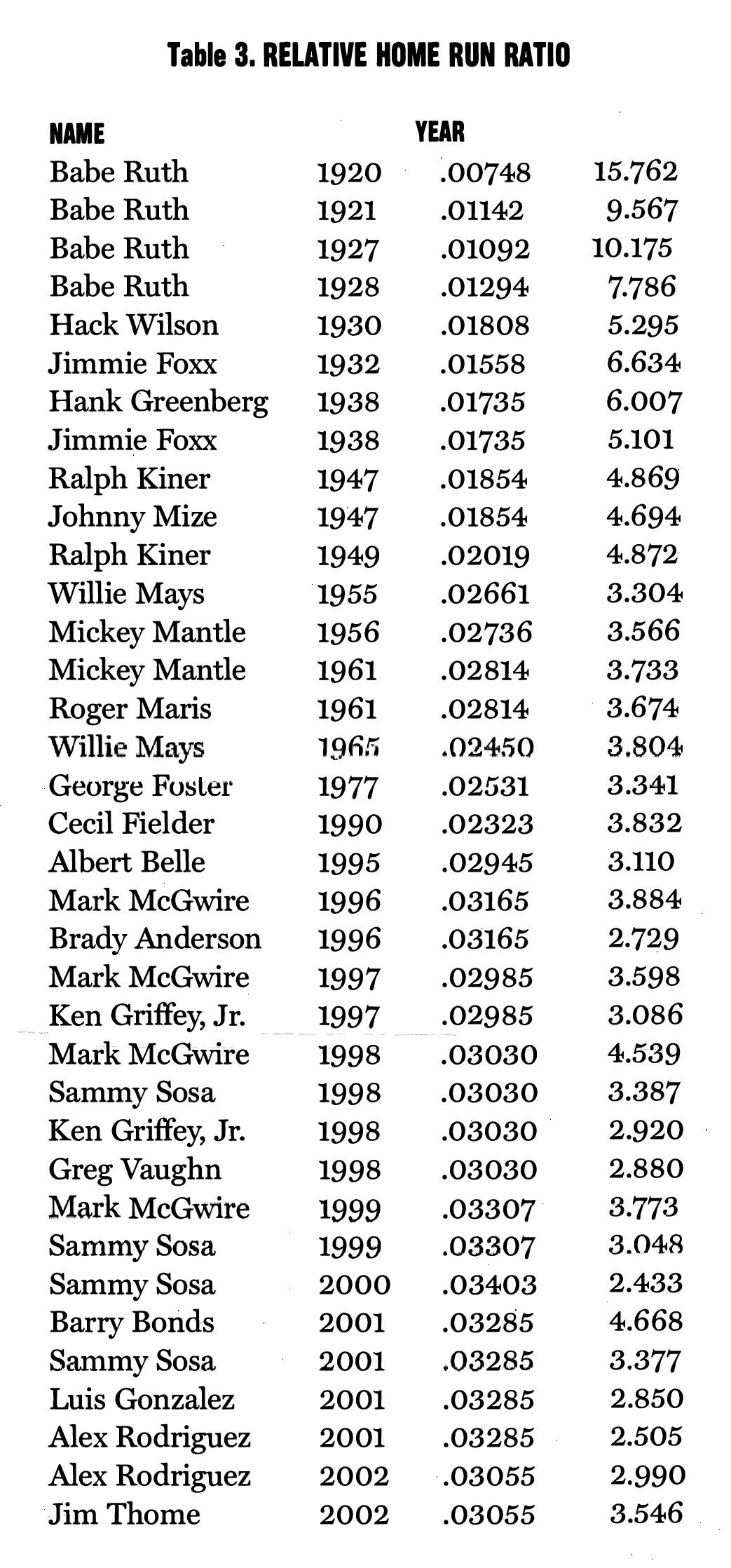

When we consider the individual home run ratio for each 50-plus homer hitter (Table 2) and compare these to the appropriate year, we get a relative home run ratio (Table 3). We see that Babe Ruth has the four highest amounts, and that his ratios in 1920, 1921, and 1927 dwarf the entire field. It is plausible to assert that not only were home runs “harder to hit” in Ruth’s time, but that no other slugger in history was close to Ruth in this relative sense.

One of the more recent measures is isolated power, which is defined as slugging percentage minus batting average. Babe Ruth is the career leader with .348. In comparison, Mark McGwire has an ISO of .325 while Barry Bonds’ ISO is .300.

Another statistic is called the total power quotient. It is defined as the sum of home runs plus runs batted in plus total bases, all divided by at-bats. That is, TPQ =

HR + RBI + TB

AB

Ruth is number one in career TPQ with 1.0382, placing him well ahead of both McGwire’s 0.9109 and Bonds’ 0.8670.

The most commonly used “new” statistic is, perhaps, that of on-base plus slugging (sometimes called production). This is defined as the sum of on-base average and slugging percentage:

OPS = PRO = OBA+ SLG

Babe Ruth, at 1.167, ranks first in lifetime OPS, well ahead of Barry Bonds’ 1.023 and Mark McGwire’s 0.982. Ruth’s 1920 standard of 1.379 was edged by Bonds’ 2002 mark of 1.381, but Ruth has six of the ten best seasons ever with respect to OPS, compared to two held by Bonds. Boston Red Sox great Ted Williams considered this the superior measure.

Williams called it “…the bottom line in hitting …”4 When dominance is considered, Ruth is so far ahead of his contemporaries that comparisons are virtually impossible to make.For example, with regard to slugging percentage, he won 13 titles in 14 years, an unparalleled feat, and he is the only player ever with two .800+ seasons.

Ruth more than holds his own when compared to the new breed of super sluggers. For example, Babe’s seasonal records for runs scored (177), total bases (457) and extra-base hits (119) are astounding, especially when realizing that these marks were accomplished during 154-game seasons.

Despite the home run barrage of the past several years, consider the following:

- Babe Ruth has more American League home run crowns than any player in history with 12 (including two ties).

- Babe Ruth has more major league home run crowns than any player in history with 11 (including three ties).

- No one has more 50-plus homer seasons than the four that Ruth accomplished.

- No other player in any decade hit as many home runs, 467, as Ruth hit in the 1920s.

- No other player has as many multiple home run games as the 72 posted by the Babe.

- No other player has as many slugging percentage (SLG) titles as the 13 posted by Babe Ruth.

- No other player has as many on-base plus slugging (OPS) titles as the 13 recorded by the Bambino.

- No other player has as many runs scored titles as the eight that Ruth accomplished.

- No other player has as many runs batted in crowns as the eight posted by the Babe.

- Ruth led the league in bases on balls 11 times, more than any player in history.

- No player in history has more extra base hits titles than the seven recorded by Ruth.

- Ruth is the only player in the Hall of Fame to have pitched in at least ten different years with more wins than losses in each season.

Though some of his records have fallen, when considered as a conglomerate, his overall rating must remain number one.

In the final analysis, some may feel that his throne is a bit tarnished.Others may wonder if some of the glitter has faded from his crown. But no one — neither Ted Williams nor Lou Gehrig from the past — not Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, or Barry Bonds from the present — can usurp Ruth’s merited title. Like fine wine, the Sultan of Swat improves with age.

FR. GABRIEL B. COSTA is an associate professor teaching in the department of mathematical sciences at the United States Military Academy at West Point. He has previously been published in The Baseball Research Journal and Elysian Fields Quarterly.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Lyle Spatz of SABR and John T. Saccoman of Seton Hall University for their invaluable suggestions and assistance.

James, Bill. The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, rev. ed. New York: Villard Books, 1988.

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, New York: Free Press, 2001.

Thorn, John, and Pete Palmer, eds.The Hidden Game of Baseball, rev. ed.Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1985.

Williams, Ted, and Jim Prime. Ted Williams’ Hit List, Indianapolis, IN: Masters Press, 1996.