Babe Ruth in Hot Springs: The Home Runs That Changed Everything

This article was written by Michael Dugan - Bill Jenkinson - Don Duren

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

“I saw it all happen, from beginning to end. But sometimes I still can’t believe what I saw. This 19-year-old kid, crude, poorly educated, only lightly brushed by the social veneer we call civilization, gradually transformed into the idol of American youth and the symbol of baseball the world over – a man loved by more people and with an intensity of feeling that perhaps has never been equaled before or since.” — Harry Hooper, Babe Ruth’s Red Sox teammate1

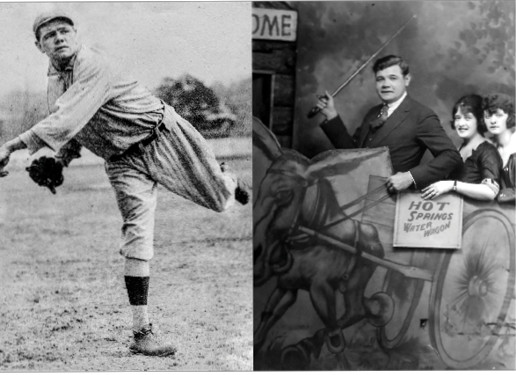

Left: Babe Ruth on the mound at Majestic Park in Hot Springs, Arkansas, during his first spring with the Red Sox. March 1915. Right: Babe and first wife, Helen, at the Happy Hollow Amusement Park in Hot Springs. Behind Helen is Edna Bancroft, wife of Hall of Fame shortstop Dave Bancroft. March 1921. (Image editing by Tim Reid III of ltr3designs)

Hercules Meets Hot Springs

Babe Ruth first arrived in Hot Springs, Arkansas, on March 6, 1915, a rookie pitcher for the Boston Red Sox. As was their custom, the Red Sox lodged at the Majestic Hotel, one of the town’s preeminent spa hotels. Babe was immediately smitten with Hot Springs, then regarded as “the Mecca of professional base ball players.”2 It was the most exotic place he had ever seen. The warm baths, mountain vistas, golf courses, horse races, and attractive women seemed like a dream. Until 1914, his world had been mostly limited to the waterfront streets of Baltimore or the inside of St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys.3

Twenty-year-old Babe Ruth was an unstoppable force of nature. The 6-foot-2-inch, rock-hard, 200-pound juggernaut hit the ball harder, pitched better, hiked with more stamina, and ate more food than anyone in town. Pitching in an intrasquad game on March 23, 1915, Ruth belted a savage line-drive home run to right-center field that left witnesses in disbelief. Despite Boston’s talent-laden pitching staff, Ruth earned a place in their starting rotation, eventually winning 18 games as a rookie.4

The Red Sox returned to Hot Springs in 1916 and 1917, and Babe Ruth kept getting better. He won 23 games and led the league with a spectacular 1.75 ERA in 1916. The next year he led the majors with 35 complete games, posting a stellar 2.01 ERA. Over the course of those two seasons, the southpaw from Baltimore amassed an imposing total of 650 innings pitched. During those first three years (1915-1917), he also belted nine home runs. Everyone knew Babe could hit, but his greatness as a pitcher virtually assured that he remained on the mound. But then, larger events intervened.5

With the Great War raging in Europe, many big-league players joined the conflict. That included Red Sox player-manager Jack Barry. Accordingly, owner Harry Frazee signed former International League President Ed Barrow to take over as manager. Barrow was an intelligent, competent man, but he was also humorless and unimaginative. Barrow believed converting Babe Ruth to a position player in 1918 would have made him “the laughingstock of baseball.”6

The Wizard of Whittington

“Every ball player in the park said it was the longest drive they had ever seen … soaring over the street and a wide duck pond, finally finding a resting place in the Ozark Hills.” — Edward Martin, Boston Globe7

“Before the echo of the crash had died away the horsehide had dropped somewhere in the vicinity of South Hot Springs. … The sphere cleared the fence by about 200 feet and dropped in the pond beside the Alligator Farm, while the spectators yelled with amazement. …” — Paul Shannon, Boston Post8

Babe left Boston by train for Arkansas on March 9, 1918. He was in peak physical condition after spending the winter with his wife in a remote cottage in rural Sudbury, Massachusetts. He chopped wood all winter, and vigorously engaged in various winter sports and activities.9

During his first week of practice in Hot Springs, Ed Barrow worked all his pitchers hard, making them hike over mountains, shag fly balls, and take infield practice. Barrow had already decided that big-league teams carried too many pitchers, and he wanted his hurlers in optimum shape to handle the increased workload. Yet, in those early stages, Ruth had looked comfortable at first base, and, as usual, had clubbed several batting-practice homers.10

So when regular first baseman Dick Hoblitzell was not ready to play in the opening exhibition game, Barrow inserted the 23-year-old Bambino into his position. The game was played at Whittington Park on March 17 against the Brooklyn Dodgers (aka Robins). It was the first time Ruth ever played against a major-league team in any position other than pitcher.11

Batting in the fourth inning, Babe lined a mammoth shot to deep left-center field that landed in a distant woodpile, enabling Ruth to easily circle the bases. Two innings later, Babe did even better. This time he unloaded a drive to right-center field that passed so far over the fence that it landed across the street in the Arkansas Alligator Farm, a well-known tourist attraction. The blow was so amazing that even the Dodgers stood up and cheered. None of them had ever seen anybody hit a baseball with such astonishing force. It was surely the longest home run ever hit, and may even have been the first to land over 500 feet on the fly.12

Six days later, on March 23, Babe wowed the crowd at the newly built Army training center, Camp Pike, in North Little Rock, launching out five home runs in a batting exhibition. The troops loved him.13

Word of these remarkable events quickly circulated around the baseball community, and everyone wondered if they would ever be reprised. The very next day, Saturday, March 24, the Red Sox again faced the Dodgers at Whittington Park. Barrow started Carl Mays on the mound but had to use Babe Ruth in right field due to the ongoing manpower shortage. Again, Ruth was in the field more due to chance than actual design, and, again, he took advantage.14

In the third inning, he smashed another tremendous home run to right-center field, a grand slam that cleared a pond just to the right of the same Alligator Farm. Stunning the crowd, Babe had launched this drive even farther than the second St. Patrick’s Day blast. Without question, it flew well over 500 feet.15

Polo Grounds Potentate

“Babe Ruth could hit a ball so hard, and so far, that it was sometimes impossible to believe your eyes. We used to absolutely marvel at his hits. Tremendous wallops. You can’t imagine the balls he hit.” — Opposing pitcher and teammate Sad Sam Jones16

Despite his inconceivable display of slugging power in Hot Springs, when the regular season opened at Fenway Park on April 15, Babe was the starting pitcher, hurling a masterful four-hitter against the Athletics. Three weeks later, though, he swatted two jaw-dropping home runs against the Yankees at the Polo Grounds, one on May 4, one on May 6. Before hitting the first, he hit a rocket-shot foul into the right-field upper deck. Additionally, Babe slammed three homer-length fouls during that same game, as well as a 440-foot double to the exit gate in deep right-center.17

Baseball writer and historian Fred Lieb described Ruth’s phenomenal power and intimidating impact in this way:

“[Despite the] soggy, lifeless ball of 1918 [Ruth] chilled [the] blood of pitchers … rocket[ing] home runs out of stadiums [and, on May 8] going 5 for 5, with three doubles and a triple.”18

Babe’s superhuman performances in New York left an indelible impression on fans, press, and, perhaps most important of all, Yankees co-owner Jacob Ruppert, who witnessed it from his owner’s box, usually, if not always, with Harry Frazee sitting by his side. Ruppert offered to buy Ruth from the Red Sox in 1918, but Frazee refused. It took a drastic change of financial circumstances for Frazee, Ruppert’s deep pockets, and the help of Yankees co-owner Cap Huston before Frazee agreed to sell Ruth, and other Red Sox stars to the Yankees, in what infamously became reviled in Boston as the “Rape of the Red Sox.”19

New York fans were in awe of Ruth. As Paul Shannon of the Boston Post reported, Ruth was “the hitting idol of the Polo Grounds.” As sensational a pitcher as Babe was for the Red Sox, it was his breathtaking shows of unimaginable slugging against the Yankees that resulted in his becoming a Yankee himself. The die was cast.20

The Great, Powerful, and Beloved Babe Ruth

“Every so often some superman appears who follows no set rule, who flouts accepted theories, who throws science itself to the winds and hews out a rough path for himself by the sheer weight of his own unequaled talents. Such a man is Babe Ruth in the batting world and his influence on the whole system of batting employed in the major leagues is clear as crystal.” — Baseball writer F.C. Lane21

“Don’t tell me about Ruth. I’ve seen what he did to people; fans driving miles in open wagons through the prairies of Oklahoma to see him in exhibition games as we headed north in the spring. Kids, men, women, worshippers all, hoping to get his name on a torn, dirty piece of paper, or hoping for a grunt of recognition when they said ‘Hi Ya, Babe.’ He never let them down, not once. He was the greatest crowd pleaser of them all.” — Babe’s Red Sox and Yankee teammate Waite Hoyt22

Those moonshots at Whittington Park in March of 1918 had initiated a series of occurrences nobody could control. Even “Simon Legree” Barrow was no match for the inevitability of Babe’s herculean power at the plate, nor for his popularity with the fans. So awesome was his slugging that Babe rarely appeared on a major-league mound again after his years with the Red Sox, pitching only five regular-season games during his 14 years with the Yankees, (1920-1934), the winning pitcher in every one.23

Babe basically gave up pitching after his years with Boston, but he did not give up Hot Springs.

He often returned for preseason conditioning and fun during the Roaring Twenties and beyond.

He took the baths, hiked the trails, bet the ponies, enjoyed the nightlife, and played a lot of golf.

What he did in regular seasons, however, is what made him the most famous and beloved sports figure in American history. He revolutionized the game of baseball with the unprecedented number and splendor of his home runs, a mind-boggling 659 of them with the Yankees.

Beginning in March of 1918 in Hot Springs, Arkansas, Babe changed baseball forever.24

“The Home Runs That Changed Everything” was researched and written collectively by the Hot Springs Historic Baseball Trail Research Team. All are members of SABR, and all were founding members of the Hot Springs Historic Baseball Trail, under the direction of Hot Springs civic leader, Steve Arrison. Additionally, all also served as historical advisors, and appeared in, Larry Foley’s 2015 Emmy Award winning film documentary, “The First Boys of Spring.” These “Trailmen” are:

MARK BLAEUER toiled in the field (and labs) of archeology for years. As a ranger for two decades at Hot Springs National Park, he is deeply familiar with park history. He is also an accomplished poet, whose work, including translations, can be found in 80-plus journals. A devoted researcher, he is the country’s leading scholar on African-American baseball history in Hot Springs. Mark is the author of Didn’t All the Indians Come Here? Separating Fact from Fiction at Hot Springs National Park (2007), Fragments of a Nocturne (2014), and Baseball in Hot Springs (2016).

MIKE DUGAN was born and raised in Hot Springs. His Irish ancestors came to town in 1870 and settled on Whittington Avenue, less than a hundred yards from the site which later became the national epicenter of major-league spring training. Mike served as Sports Information Director at Henderson State University before becoming a business and community leader in Hot Springs. Henderson has honored Mike with its “H” Award as Outstanding Alumni and inducted him into its Red- die Athletic Hall of Honor. A member of SABR since 1992 on the Dead Ball Era and College Baseball committees, Mike has been a major, long-time, and multifaceted, contributor to baseball history in Hot Springs. He even portrayed Royal Rooter leader, Michael T. McGreevy, in The First Boys of Spring! Nuf Ced!

DON DUREN is the great-great-great grandson of Arkansas pioneer Granville Whittington. He grew up playing baseball on the historic diamonds of Hot Springs, including where Babe Ruth played, at Majestic Park and Whittington Field. Following decades of groundbreaking, exhaustive research, he authored Boiling Out at the Springs: A History of Major League Baseball Spring Training at Hot Springs, Arkansas (2015); Bathers Baseball: A History of Minor League Baseball at the Arkansas Spa (2011); and Lon Warneke: The Arkansas Hummingbird (2014). Don now resides outside of Dallas, Texas, working as Christian minister.

BILL JENKINSON is a renowned baseball scholar, known inter- nationally for his groundbreaking research of major-league baseball’s most significant sluggers and long-distance home runs. He is the world’s leading authority on Babe Ruth’s batting prowess, “the Babe Ruth of Babe Ruth historians,” as he has been referred to by media, colleagues, and fans. Bill has served as a consultant to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Major League Baseball, SABR, ESPN, and the Babe Ruth Museum. He has appeared on numerous television and radio broadcasts and has been quoted in nearly every major newspaper in America, as well as by Time, Newsweek, and Sports Illustrated, and many other leading magazines. Bill’s books on baseball include The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs: Recrowning Baseball’s Greatest Slugger (2007), Baseball’s Ultimate Power: Ranking the All-Time Greatest Home Run Hitters (2010), and Babe Ruth: Against All Odds, World’s Mightiest Slugger (2014). Bill is the world’s leading authority and archivist of historic, long-distance home runs, including The Babe’s game-changing home runs of 1918 in Hot Springs. Bill was a primary designer of the Hot Springs Historic Baseball Trail.

TIM REID, together with his cousin and colleague Bob Ward, founded the St. Petersburg and National committees to commemorate Babe Ruth. Teamed with other historians, they have very extensively researched and noted Babe Ruth’s Ruthian contributions to baseball and American culture. Thanks especially to Bill Jenkinson, and to several members of the Ruth Family, the Committee to Commemorate Babe Ruth’s research and commemorations has significantly contributed to baseball history. Tim also writes baseball tribute songs on occasion, including “Babe Ruth, King of ‘Em All,” and “Take Me Out to the Ball Fields of Old Hot Springs.” Tim is currently researching early twentieth-century baseball in Baja California, including Babe Ruth’s Prohibition-Era adventures in the Mexican state.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks and dedication to Steve Arrison, Creator of the Hot Springs Historic Baseball Trail.

Notes

1 Lawrence S. Ritter, The Glory of Their Times (New York: Macmillan Company, 1966), 137.

2 Jay Jennings, “When Baseball Sprang for Hot Springs,” Sports Illustrated, March 22, 1993.

3 “Majestic Hotel,” in Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=8351, accessed December 3, 2018; Jay Jennings, “When Baseball Sprang for Hot Springs”; Brother Gilbert, C.F.X., Young Babe Ruth: His Early Life and Baseball Career, from the Memoirs of a Xaverian Brother (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1999), 1-4; Robert W. Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974), 27-33; Kal Wagenheim, Babe Ruth: His Life and Legend (Boca Raton, Florida: “Florida Atlantic University Digital Library, 1999), 10-14, 30.

4 T.H. Murnane, “Babe Ruth’s Home Run Drive Is His Undoing,” Boston Globe, March 24, 1915; Allan Wood, Babe Ruth and the 1918 Red Sox (Lincoln, Nebraska: Writers Club Press, 2000), 77.

5 Babe Ruth Central: “Babe Ruth’s Pitching Stats,” baberuthcentral.com/babe-ruth-statistics/babes-ruthsfull-baseballstatistics/babes-ruths-pitching-stats/, accessed December 3, 2018; Bill Jenkinson, “Where Pitchers Became Legends,” Hot Springs Historic Baseball Trail, hotspringsbaseballtrail.com/untold-stories/hot-springs-where-pitchers-became-legends/, accessed December 3, 2018.

6 “15 Red Sox Enlisted,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 18, 1918; Creamer, 152; Babe Ruth, The Babe Ruth Story, as told to Bob Considine (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1972, 14th reprinting), 60.

7 Edward Martin, “Babe’s Crash Good for Four Sox Runs,” Boston Globe, March 25, 1918.

8 Paul Shannon, “Ruth Smashes Up Hopes of Dodgers,” Boston Post, March 25, 1918.

9 Edward Martin, “Ruth Here to Talk Salary with Frazee,” Boston Globe, January 10, 1918; Mel Webb, “Babe Ruth, of the Red Sox, Spending Winter Among the Pines,” Boston Globe, January 20, 1918; Paul Shannon, “Red Sox Given First Workout,” Boston Post, March 13, 1918; Paul Shannon “‘Rainbow Ball’ Marks Practice,” Boston Post, March 14, 1918; Bill Jenkinson, The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2007), 24-27.

10 Wood, 15; Wagenheim, 36-37.

11 Wood, 15, 16.

12 Literature and ephemera provided by June Koffi, David Diakow, and Mark Levine, of the Brooklyn Central Library’s Collections, Biography, and Sports departments, respectively; Brooklyn, New York, December 2018; Paul Shannon, “Red Sox Hammer Dodgers,” Boston Post, March 17, 1918; “Superbas Helpless Against the Swatting of Babe Ruth,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 18, 1918.

13 Leigh Montville, The Big Bam (New York: Random House, 2006), 105, 106.

14 Edward Martin, “Babe Ruth a Star of First Magnitude,” Boston Globe, March 25, 1918; Paul Shannon, “Ruth Smashes Up Hopes of Dodgers,” Boston Post, March 25, 1918.

15 Tim Reid and L.T. Reid, III, “Baseball’s First Five-Hundred Foot Home Run/Diagrams of Babe Ruth’s Historic Hot Springs Home Runs of 1918,” firstfivehundredfoothomerun.jimdo.com/home-run-diagrams/, accessed December 3, 2018.

16 Ritter, 230, 232.

17 W.J. MacBeth, “Russell Outpitches Ruth, Humbles Red Sox Clan 5 to 4,” New York Tribune, May 7, 1918; Frederick G. Leib, “Murderers’ Row Batters Red Sox,” New York Sun, May 7, 1918; W.J. MacBeth,“Ping Bodie Brings Glory to Yankee Escutcheon,” New York Tribune, May 7, 1918; “Babe Ruth’s Fine Clouting Stunt,” Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer, May 7, 1918.

18 Marshall Smelser, The Life That Ruth Built (New York: Quadrangle/New York Times Book Co., 1975), 98.

19 Michael T. Lynch, Harry Frazee, Ban Johnson, and the Feud That Nearly Destroyed the American League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008), 84; Frederick G. Lieb, The Boston Red Sox (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003), 178.

20 Ruth, 82-83; Paul Shannon, Boston Post, May 6, 1918; “Sox Vanquish Yanks, 7 to 3,” Boston Herald, June 25, 1918; Wood, 39.

21 John E. Dreifort, Editor, Baseball History from Outside the Lines: A Reader (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 125.

22 “Waite Hoyt Remembers the Babe,” baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/short-stops/waite-hoytremembers-babe-ruth, accessed December 3, 2018.

23 Hardball Times, “Babe Ruth, the New York Pitcher,” tht.fangraphs.com/babe-ruth-the-new-york-pitcher/.

24 “Babe Ruth’s Last Visit to Hot Springs,” hotspringsbaseballtrail.com/untold-stories/babe-ruths-last-visit-hot-springs/, accessed December 3, 2018; Baseball Reference, “Babe Ruth, Summary of 714 Home Runs,” baseball-reference.com/players/event_hr.fcgi?id=ruthba01&t=b; “100 Greatest Baseball Players,” Baseball Almanac, baseball-almanac.com/legendary/lisab100.shtml, accessed December 3, 2018; “The 40 Most Important People in Baseball History,” The Sporting News, sportingnews.com/us/mlb/news/most-important-influential-people-in-mlb-baseball-history-list-players-owners-general-managers/1uga2utsurjcc19cwjmsz47apr, accessed December 3, 2018; Seth Everett, “Babe Ruth Awarded Presidential Medal of Freedom,” Forbes, November 19, 2018, forbes.com/sites/setheverett/2018/11/19/babe-ruth-awarded-presidential-medal-offreedom/#3f1ea0004913.