Bacteria Beat the Phillies: The Deaths of Charlie Ferguson and Jimmy Fogarty

This article was written by Jerrold Casway

This article was published in Spring 2016 Baseball Research Journal

Between the years 1888 and 1891, the National League Philadelphia Phillies lost two prominent ballplayers on what promised to be contending teams. In an age when the life expectancy for American men was 46 to 53, it was surprising to see athletically-fit young men in their mid-twenties die before their expectant lifespan.1

This fate, however, was not unanticipated. The late nineteenth century was still lacking medicines for infectious diseases and questions persisted about how these illnesses were contracted and spread. Baseball players, in spite of their athletic conditioning, were just as susceptible as the general population to the ravages of disease. The perceived invulnerability of the healthy athlete was just a delusionary product of a ballplayer’s notoriety.

Typhoid fever, diphtheria, and Consumption (tuberculosis) were the troubling diseases for men who travelled widely, worked in confined and crowded spaces, and practiced lifestyles that ran down their immune systems. Once a body lost its resistance to disease, the factors from exposure took their toll.

Both typhoid fever and tuberculosis were bacteriaborne. The typhoid bacteria grew in the intestines and blood stream and were induced by contaminated water, unpasteurized dairy products, raw eggs, and the unwashed skins of raw vegetables and fruit. In general, the disease was a product of improper sanitation. It led to high fevers, abdominal pains, headaches, and constipation. A person carrying the disease might not be affected by it, but could pass it on to more susceptible victims. In 1891, typhoid death ratios in Chicago were 174 per 100,000 people.2 Tuberculosis was more threatening and widespread.

Tuberculosis was often called Consumption because the disease wasted a body through its pulmonary affliction: a person was, in essence, “consumed” by the bacteria. The Greeks called it the “wasting disease.” Tuberculosis was also quite contagious: coughing, sneezing, spitting would expel infectious droplets, sometimes in a blood form. It was said that in the late nineteenth century, an afflicted person could infect 10 to 15 people a year.3 Weight loss, fatigue, chest pains, and bloodied sputum were the most apparent symptoms. By the turn of the century, tuberculosis was the leading cause (25%) of death in the United States. Vulnerability to the bacteria often was brought on by a weakened immune system that could be accelerated by excessive drinking and smoking. But the congregating of people was the decisive factor for the disease’s transmission.4

The incidence of tuberculosis among ballplayers never reached epidemic proportions. We only know of eight recorded deaths among late nineteenth-century ballplayers. Jimmy Fogarty, the Phillies’ fleet-footed outfielder, was the most prominent victim. The same could be said for typhoid fever. Only the deaths of four ballplayers were attributed to this illness. Again, the Phillies had the most significant victim, their star pitcher and batsman Charlie Ferguson.5 For the unfortunate Phillies, both players were considered critical pieces for a pennant-contending ball club.

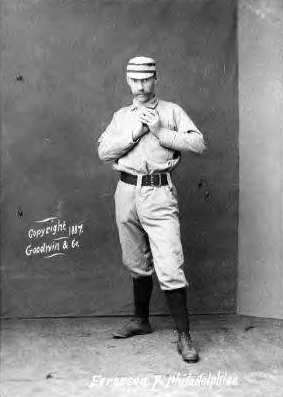

Ferguson was born in rural Charlottesville, Virginia, during the Civil War on April 17, 1863. His father was a baker and an entrepreneurial businessman in a largely Irish community known as Random Row. How Charlie picked up an interest in baseball is not known, but the war had greatly popularized the game in the South, especially a border state like Virginia. Although there was speculation that he attended the University of Virginia, no record of his enrollment exists. It is probable that he played ball with a team that had some affiliation with the university in his hometown in 1882. His play attracted the attention of a Richmond merchant who owned a ball club in the Virginia capital. In 1883, Ferguson signed and pitched for that Richmond club. His performance at Richmond caught the attention of scouts for the new Philadelphia baseball franchise. Under the management of Al Reach, the club signed Charlie Ferguson in 1884 for $1,500.

In his first season, the 21-year-old Ferguson had a 21–25 record in 417 innings. His ERA was 3.54 for a team that finished 39–73. Before the start of the following year, Ferguson married the 18-year-old Mary Smith. The coming season also gave notice of his baseball potential. He was 26–20 with an ERA at 2.22. He even pitched the franchise’s first no-hitter against the Providence Grays. But Ferguson also showed great promise with the bat and played 15 games in the outfield. He actually led the team in batting average, .306 in 235 at-bats. Nothing he did in 1885 prepared the league for his next season’s performance. Ferguson was 30–9 with a 1.98 ERA. His WHIP was .976, the second best in the National League. He finished the season with 11 straight wins.

However, at the end of August 1886, Ferguson and some of his teammates became sick during an extended heat wave on a western road trip because of “bad water in the west.” Initially, Ferguson and George Wood were sent home to recover, but when Charlie returned to the team his illness re-emerged. Again he asked Harry Wright for permission to leave the ball club. These incidents may have foretold that something was wrong with the Phillies’ ace pitcher.

Although Ferguson was enjoying his best season, he had pitched 396 innings after a 405-inning campaign the previous year. He might have been 23 years old, but those were a lot innings for a pitcher who also played the outfield. Actually there were two main issues affecting the young Ferguson. First, Charlie complained of a weak arm and general fatigue when the team left Philadelphia on that last road trip. But Wright refused to give him permission to return to his Charlottesville home. Ferguson was torn by this decision because he did not want to take a “French leave” of the team.6

Ferguson asserted that he was too weak to perform up to his own standards. He said he had been overworked in the previous Detroit series and got very little offensive support from the team. Charlie confessed that he did not welcome bearing the brunt of the pitching load in Chicago the way he was feeling.7 He said, “I have worked hard and faithfully and have given my manager very little trouble by always trying to please him.” Ferguson told reporters that Wright did not appreciate the gravity of his condition. Unable to get Wright’s support, Ferguson took a train out of Chicago and went home to Virginia. He claimed he was bedridden for ten days and had a doctor’s certificate to validate his condition.8

A few of his teammates doubted his illness and said it was a case of “home sickness” or “chicken heartedness.”9 This commentary made little sense. It was probably an expression of some players’ frustration with Charlie’s state of mind. He was worn out and was distressed about his salary and with a troubling situation at home. Another factor was that Ferguson was a hypochondriac, “a confirmed crank on the subject of health.” Apparently, he was frequently afflicted with imaginary aliments. He even carried a medicine chest on road trips. It was said that Ferguson “swallowed enough medicine to kill an ordinary healthy man.” His teammates joked that he would pitch a good game whenever he was ailing.10 But manager Wright believed Ferguson was imagining one of his illnesses and was upset by the departure of his star player and suspended him for the remainder of the season. He also fined him $200 and threatened to blacklist him for his actions.11 When Ferguson returned to Philadelphia at the end of the year, he told John Rogers, the team’s litigious treasurer, that “I will lick someone before I leave this city … [without my full] salary.”12

Not spoken about during this controversy was the fact that Ferguson was worn down, possibly setting the stage for his eventual date with typhoid fever. Although newly married, the young Ferguson was still a fashionable man-about-town, who kept a highprofile lifestyle. Between the on-field demands on his physicality and his after-hours activities, Ferguson’s resistance was put in jeopardy.

As Ferguson was wearing down, he again returned to the topic of compensation. Few in the league pitched or played more innings than Charlie, but he was dealing with a franchise that had the lowest salary scale in the league. It was judged that no Phillies player approached the league’s $2,000 maximum. Not to be overlooked was Charlie’s grievance about last season’s $200 fine. Having been paid $1,800 for each of the last two years, Ferguson believed his performance had earned him a raise. He reacted by joining three teammates in early November 1886 in demanding enhanced contracts for the upcoming season.13 To make extra money Ferguson and many of his teammates planned to play an extended exhibition tour in Cuba that winter. Ferguson, however, had second thoughts and for unspecified reasons stayed home in Virginia with his wife and their ailing baby.14

The Phillies, like other clubs, were feeling the pressure for higher salaries from the newly-formed players’ Brotherhood. Ferguson and a number of his teammates were early and active members of this unionized organization. They responded by refusing to go south for spring training unless the team acceded to their salary demands. Ferguson held out for $3,000. Eventually, he relented and said he would sign for $2,800. Harry Wright, however, was only authorized to offer him $2,500. Charlie refused this offer and remained in Philadelphia. The Sporting News reported that any ball club would gladly pay this “crack” pitcher $3,000. But manager Wright believed that Ferguson would eventually come around before the team returned from the south. In the meantime, he coached baseball at Princeton College. He said he would return to Richmond after his coaching commitment was over.15 Caught in a financial bind, Ferguson relented and signed for $2,500, a $700 raise over his last contract.

He did not disappoint management. He was 22–10 with a 3.00 ERA, third best in the league even though he was put off by the new pitching rules affecting the pitching box and the placement of his pivot foot.16

Ferguson also became the team’s second baseman when he was not pitching. He batted .337 and led the team with 85 RBIs. More remarkably, unlike 1886, he finished the year in a flurry. The Phillies won 16 out of their last 18 games. Charlie either pitched or played the field in each of these contests. He was 7–0 as a pitcher with a 1.75 ERA and batted .361. Thanks to his efforts, the Phillies moved into second place behind the power-laden Detroit Wolverines. Ferguson’s performance was so impressive that a number of teams offered to buy his contract. It was reported that one club proposed $10,000 for Charlie’s services. President Al Reach rejected all offers for his star player.17

Unfortunately, Ferguson’s season was marred by the tragic death in June of his infant daughter. As indicated above, Charlie threw himself into his ball playing. He appeared in 72 of 128 games (59%), had 264 at bats, and pitched 297 innings. Nevertheless, he went out to the West Coast after the season and played ball until his arm gave out. At this point a weary Ferguson returned east.18 It was obvious that the rigors of the 1887 season had sapped his strength and brought on another bout of the exhaustion that had afflicted him at the end of 1886.

Ferguson was depleted and very much run-down. He had lost some of his 170 pounds. In this weakened condition he was exposed to contaminated liquids or was infected by a bacteria carrier. Initially, Ferguson appeared normal and again coached baseball at Princeton. After he belatedly signed his 1888 contract, he played second base in early April preseason exhibitions against the American Association Athletics.

Although Ferguson’s offense was lacking, he did play well in the field and was considered the team’s regular second baseman.19 By mid-April 1888 he began to exhibit signs of the illness. It began with a high fever that was first diagnosed as malaria. But when red spots appeared on his chest, the diagnosis changed to typhoid. He was now confined to bed in his Broad Street residence in north Philadelphia for about three weeks. It was hoped that this convalescence would quell the disease. President Reach responded by bringing in Dr. William Pepper, a renowned physician at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital. He joined two other doctors who were attending Ferguson. Using hypodermic injections, they stabilized Ferguson’s blood pressure, but his high fever remained unbroken.

On Saturday, April 28, his illness took a turn for the worse. By noon he sank into unconsciousness and all hope began to fade.20

Early that evening teammates began to arrive. He awoke when they spoke to him. Ferguson asked about that afternoon’s game against New York. They told him they had lost and he softly commented, “We are certainly having bad luck this year.” Ferguson then asked Sid Farrar to come closer and said, “Sid, I am afraid I am going to die.” Before Farrar could respond, Charlie again lost consciousness. The players went to get Ferguson’s young wife, Mary, who was reluctant to enter the room. Soon after her coming to his side, the doctor pronounced him dead. She became hysterical and passed out. By the time he died, most of his teammates, with the exception of Al Reach, John Rogers, and Harry Wright, were at the house.21

The Sporting News joined other publications in mourning and lauding this extraordinary athlete. He had turned 25 only 12 days before his death. The paper said, “He was a gentleman of the highest degree and a great ballplayer. He had more friends than any player on the club.”22 Ferguson was what we call today a five-tool player. He did everything well. His teammates and friends organized a benefit game for Ferguson’s widow. The exhibition raised $406. The Phillies also paid his medical and funeral expenses. He was buried in Maplewood cemetery in Charlottesville, Virginia.23 Ferguson, like his father, was investment-conscious and his wife was left a number of Charlottesville properties.

The Phillies abruptly lost their star player to a bacterial infection. Many teams commemorated Charlie by wearing black armbands. But his ball club knew they could not replace a man whom the Boston press called “Ferguson Furioso.”24 No pitcher could fill that void in their rotation. They did find someone to take his place at second base, a youngster from Cleveland named Ed Delahanty.

Between the years 1888 and 1891, the National League’s Philadelphia Phillies lost two prominent ballplayers on what promised to be contending teams. In an age when the life expectancy for American men was 46 to 53, it was surprising to see athletically fit young men in their mid-twenties die before their expectant lifespan.1 This fate, however, was not unanticipated. The late nineteenth century was still lacking medicines for infectious diseases and questions persisted about how these illnesses were contracted and spread. Baseball players, in spite of their athletic conditioning, were just as susceptible as the general population to the ravages of disease. The perceived invulnerability of the healthy athlete was just a delusionary product of a ballplayer’s notoriety.

Between the years 1888 and 1891, the National League’s Philadelphia Phillies lost two prominent ballplayers on what promised to be contending teams. In an age when the life expectancy for American men was 46 to 53, it was surprising to see athletically fit young men in their mid-twenties die before their expectant lifespan.1 This fate, however, was not unanticipated. The late nineteenth century was still lacking medicines for infectious diseases and questions persisted about how these illnesses were contracted and spread. Baseball players, in spite of their athletic conditioning, were just as susceptible as the general population to the ravages of disease. The perceived invulnerability of the healthy athlete was just a delusionary product of a ballplayer’s notoriety.

Four years later the team suffered another loss, the death of their starting center fielder, Ferguson’s teammate, Jimmy Fogarty. His death, too, resulted from a deadly bacterial infection that sapped the vitality of the franchise.

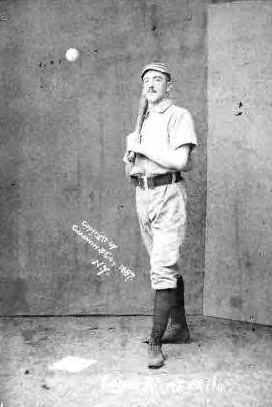

Fogarty was born on February 12, 1864, in San Francisco. His father was a railroad foreman who moved his family to Colorado before settling in California. Jimmy was the fourth of six children. Affable and companionable, Fogarty did what he pleased and enjoyed opportunities that came his way. Besides his spirited Irish personality, he was blessed with great speed and athletic coordination.

Jimmy initially played baseball for two years in the California League with the local Haverly ballclub. He soon realized that money, notoriety, and competition for baseball were better on the east coast. This recognition drew him to the new franchise in Philadelphia. In 1883, Fogarty at the age of 19 was good enough to earn a place on an experimental reserve team. Playing third base, he convinced Al Reach to retain him at lower pay as a substitute player when the reserve system was scrapped. Fogarty was confident that he could win a starting position if an opportunity arose.

In 1884, under the new Phillies manager, Harry Wright, he got his chance when outfielder John Manning was beaned by a pitched ball. Fogarty took advantage of this situation and became the Phillies’ regular center fielder.25 Within a few seasons he was acclaimed as a superior outfielder and a champion base stealer. Playing alongside Ed Andrews and George Wood, the outfield was a stable unit until Sam Thompson switched clubs and young Ed Delahanty was tried in left field. On occasion, Fogarty also played the infield and was used as a “change” pitcher when the staff was overworked.

In his first season, Fogarty played in 97 games and his batting average was only .212. The next year he raised his batting average to .232 in 111 games. In 1886 the 22-year-old Fogarty began to come into his own. He batted .293, playing in only 77 games because of an injured knee. But his physical condition did not keep Jimmy from non-ballfield distractions. He chafed over his annual salary of $1,400. At the end of the year he joined Ferguson and others demanding a raise. Fogarty warned that the $1,600 offered by the club, “won’t get him for another season.”26 The youngster even threatened Harry Wright that he might not come east in 1887.27 Despite this rhetoric, Fogarty was thinking entrepreneurial. He and the Phillies’ groundskeeper opened a “cosy little saloon” near the Phillies new ball park at Broad and Lehigh.28 His most controversial endeavor was an exhibition tour in Cuba. This commitment disappointed his friends in California, but Fogarty had money and adventure on his mind.29

The tour was organized by an enterprising insurance man, James P. Scott, and officials from the local Athletic Association club. The exhibition did not live up to its expectations. Expenses for two travelling teams were excessive. There was also competition from a famous touring Spanish bullfighter. Profits were made, but they were not satisfactory for ballplayers like young Fogarty. He claimed Scott had guaranteed him $200 above the sharing of gate receipts. Fogarty refused to play until he was paid or got a return boat ticket back to the States.

Scott and his partners condemned Fogarty’s contentious behavior. They complained that he had not paid his tailor debts and bar bills. They also castigated him for disruptions at their hotel. Fogarty was accused of bringing disreputable people into the residence where they conducted themselves with scandalous behavior.30 Other players joined Fogarty in disputing the profit-sharing plan. The discontent that followed disrupted the exhibition tour. In spite of these problems, Fogarty returned to the States and reconciled with the Phillies after they gave him a $500 raise to $1,900.

In 1887, the Phillies finished second and Fogarty had a .261 batting average in 126 games. He scored 113 runs, and led the league with 82 walks. He also stole 102 bases (as then defined) and had 39 outfield assists. During the season Fogarty stole 38 bases in 27 consecutive games. In one game he swiped six bases.31 Nevertheless, he still managed to get himself in trouble.

On the train ride south for spring training he harassed an elderly black passenger who threatened to defend himself with a concealed screwdriver.32 A more serious problem was the drinking binges that Fogarty conducted when the Pittsburgh club came to the Quaker City. Detectives followed Fogarty and his companions. They reported that on consecutive nights the ballplayers were drunk and disruptive. Fogarty was fined twenty-five dollars over and above an earlier forfeiture of fifty dollars.33

Accustomed to leading a demanding night life, Fogarty finished out the year without any further problems. However, he did overextend himself by organizing his teammates after the season on a western exhibition tour. They played games in Cincinnati, Chicago, Santa Fe, and Las Vegas, New Mexico, before arriving for a series of games in Los Angeles.34 After the tour Fogarty remained in the west until March 1888.

Wherever Jimmy Fogarty appeared, he sported a profligate lifestyle. In California, Philadelphia, or any city on the National League circuit, the flamboyant Fogarty was surrounded by his many friends and supporters. He even belonged to the Union Republican Club in Philadelphia and was the confidant of many well-placed people. His nicknames of “Master Jeems” and “The Foge” testified to his temperament and public persona as a popular man about town. Jimmy earned his reputation by keeping early morning hours at all-night social clubs. This fraternizing did nothing to quell his serious drinking, heavy smoking, and avid gambling habits. Such vices certainly contributed to his often erratic actions. Affable and charming, Fogarty could also be mean-spirited and bigoted, especially when he was drinking. Many of these traits came to a debilitating head during the next year’s baseball season.

The 1888 season was a difficult one for Fogarty. His batting average slipped to .236 and though he played in 121 games, he stole only 58 bases. Most contemporaries associated this decline with three problems. Baseball analysts said the advantage of 1887’s four-strike rule allowed him to lead the league in walks. In 1888, his tactic of taking too many pitches caused him to be less effective at the plate. Then there was the developing relationship with veteran outfielder George Wood. These “gayest young men” were inseparable late-night “sunrise socialites.” Both were constantly chided for their partying and their influence on teammates and visiting players.35 Their on-field performances suffered as a result.

Perhaps the most distractive influence was the growing union movement in professional baseball. The players’ Brotherhood, formed in 1885, attracted support from players who were upset with the prevailing reserve clause and static salaries. The Brotherhood was a ready-made cause for the restive Fogarty. Only 24 years of age, Fogarty was weaned on clubhouse union talk of many of the Phillies’ older and more militant players.

Nine of the club’s 13 players supported the union’s positions. When Art Irwin’s politics forced him to step down as team captain, Fogarty moved to ingratiate himself to manager Harry Wright. However, Wright should have known better then to consider the volatile Fogarty. He reminded Jimmy that he needed to be smart and use his brains. Fogarty, the wiseacre, responded, “You can’t throw your brains to first base and put a man out.”36

Within a few weeks, he resigned his captaincy.37 In spite of these distractions, Fogarty recovered his focus in 1889. He played in 128 games, had a .259 batting average and led the league in stolen bases (99), putouts (302), and assists (42). He also fielded at an impressive .961 clip, committing only 14 errors. But Fogarty’s real test came at the end of the 1889 season when he accompanied Albert Spalding’s overseas baseball tour.

On the tour Fogarty was exposed to the Brotherhood’s leaders, such as John M. Ward, Fred Pfeffer, Ned Hanlon, Jimmy Ryan, and of course George Wood. On the long sea voyages Fogarty was further indoctrinated to the union’s policies. When the touring players learned that the club owners had reneged on the salary cap promises and the reserve clause concessions, the commitment for a strike-driven players’ league was cast.

Soon after Fogarty arrived stateside, he declared, “We’ve got to get more money out of the game …. We attract the fans, but the owners pocket the money.”38 One owner replied, “would to heaven we could be such slaves and draw salaries from $3,000 to $5,000 for seven months work—no, play.”39 Fogarty and his mates said they were subjected to a kind of “gilded bondage.”40 Club magnates labeled the players as “hotheaded anarchists” and “seditious malcontents.”41

The players responded with a league of their own. The union league was made up of jointly-run franchises, operated by capitalist backers and ball playing employees. Each player signed a one-year contract with a two-year option to renew. Reserve and salary classification contracts were prohibited, gate receipts were shared, and home clubs got concession profits. Under these guidelines Fogarty signed with the Philadelphia union club in which he invested $2,000 of his own money.

Sometime after the 1889 season, Fogarty returned to the west coast where he and Mike Kelly worked to unionize minor league ballplayers. On February 6, 1890, Fogarty returned to the Quaker City to an enthusiastic welcome. He was named captain of the players’ team and worked incessantly to get a site for the new local Brotherhood ballfield.

All this traveling and stress began to take its toll on Fogarty. As the 1890 season approached, he fell ill. At first doctors thought he might have typhoid, but in reality he had contracted tuberculosis. Initially, George Wood was installed as Fogarty’s “head nurse.” The “Foge” recovered from the first attack, but he had not fully shaken off the bacterial infection. Once the season started, however, the weakened Fogarty was determined to lead his club to a profitable year.

By mid-May, the club was playing less than .500 ball, Fogarty’s batting average was around .230, and the club’s attendance reflected the team’s disappointing play. At this point the ball club’s major stockholders began to question Fogarty’s leadership. Reminiscent of the Cuban fiasco of 1886, Fogarty fell out with the team’s directors, primarily the club’s president, Henry Love. An ongoing feud festered between the two men. George Wood tried to placate Fogarty, but the matter had gotten out of hand. Fogarty eventually resigned the captaincy and refused to play as long as Love stayed in office. Jimmy complained about a sore foot, an injured knee, and a bad cold.

The crisis was resolved when new investors replaced Love and his supporters. But Fogarty for the remainder of the season was an inconsistent player. His stamina was drained and he was disillusioned with the whole union experiment.

Hereafter I am out for the “stuff” and will play ball for money in every sense of the word. I am done with honor and all such nonsense in connection with baseball. I stuck with the Brotherhood but the Brotherhood had not stood by me.42

The Philadelphia Quakers of the Brotherhood finished the season in fifth place. Fogarty was 7–9 as a manager/captain. He played in only 91 games, his batting average a lowly .239, and stole 36 bases. At the season’s end the union league and its ball clubs were no more. Investors made do with their losses and players looked to mend their relationships with their former teams.

But the once graceful darling of center field had pushed his body beyond its capacity. His knees were not in good condition, his hands had been burnt by a curtain fire in his bedroom, and his respiratory system was again exhibiting symptoms of tuberculosis.43 This condition was not surprising given his lifestyle and the strains of the past year. Fogarty’s consumptive bacteria were dormant and were waiting for the athlete’s body to weaken.

Jimmy Fogarty believed rest and the recuperative climate of California would allow him to recover his health and strength. Meanwhile, the Phillies debated Jimmy’s status. President Reach and manager Wright were willing to forgive the likeable and repentant ballplayer. Colonel Rogers, the sour-tempered club treasurer, with reluctance agreed to take Fogarty back.44

Jimmy accepted his reprieve and arrived in Philadelphia in early February 1891. He appeared to be in good health and spirits. Feeling like his old self, Fogarty celebrated. He hung out with his old cronies and made the rounds of his favorite night stops. But the cold weather and his long hours produced a bad cold that triggered his pulmonary problems. His condition accelerated and within a few days he was admitted to St. Joseph’s Hospital under the care of the Sisters of Charity. After his discharge it was only a matter of time before he had a serious relapse. For the next few months the ailing Fogarty went from home to home of different friends. No one was more attentive than his close companion, George Wood.

But Fogarty was a stricken man. Both his father and brother had suffered the same affliction. By the end, “The Foge” was emaciated and weighed about ninety pounds. He was now regularly attended to by a local priest. Fogarty’s constant companion was a bible that he kept on his lap.45

On May 20, Jimmy Fogarty took his last labored breath. He was only 27. His body was embalmed and conveyed in a wreath-covered coffin by train to San Francisco where he was buried. Philly players wore black arm bands and the Union Club flew their flag at half-mast. Meanwhile, Billy Hamilton, who was purchased during the strike season, took over center field and the base paths for the player known to all as “Master Jeems.”

Within a four-year span the Phillies lost two of their most popular and promising stars to dreaded bacteria-driven illnesses. Their deaths were a shock to other ballplayers, who lived their lives as if they were immune to such infections. Unfortunately, the habits of their celebratory lifestyles and their public exposures made them susceptible to whatever was circulating in their environment. Standing buckets of drinking water, congested dressing quarters, eating on the run, and hours spent on soot-ridden trains created a petri-dish setting for disease.

In this era ballplayers were responsible for their medical care. As a result, they often put off treatment believing they would recuperate in time. The problem was that pulled muscles responded to rest but that was not the case with infectious bacterial diseases. Stricken victims had little hope of recovery. Neither the victim’s youth nor an athlete’s conditioning could ward off the onslaught of a ravaging illness. Death by way of a bacterial infection was as assured as a pitched ball crossing home plate.

For the Phillies the passing of these two young charismatic players shadowed the ball club into the new century. With these deaths, the ball club also lost something of its character and vigor from which it slowly recovered.

The teams that followed never lacked dominant players—Delahanty, Thompson, Lajoie, Flick, and Hamilton each made the Hall of Fame—but these players lacked the appeal and charisma of Ferguson and Fogarty. And though both players had their issues with management, their sudden deaths from unseen bacteria took something from the life of the ball club and perhaps the city they represented.

JERROLD CASWAY is the Dean and Professor Emeritus at Howard Community College in Columbia, Maryland. He has written many articles on nineteenth-century baseball and was a featured keynote speaker at the Baseball Hall of Fame. He has written a biography on “Ed Delahanty in the Emerald Age of Baseball” (2004) and McFarland will publish his book, “The Culture and Ethnicity of Nineteenth-Century Baseball,” in 2016.

Notes

1 The 46 age figure takes infant mortality into consideration. Fifty-three years was a more agreeable number for the late nineteenth century. “Were there old people in 1900?” This life expectancy topic came from an Internet source dated February 24, 2014: Thadeusktsim.wordpress.com

2 “1900 Flow of Chicago River Reversed,” Chicago Timeline, March 7, 2007, Chicago Public Library.

3 T.B. Fact Sheet (Google) from World Health Organization, November 2010 and July 2011.

4 C. Davis, “Tuberculosis Facts,” December 8, 2014, Google.

5 Christy Mathewson died from tuberculosis after his lungs were weakened during a gas training accident in France.

6 A “French leave” is a leave without permission or saying goodbye.

7 The Sporting News, September 27, 1886; September 20, 1886.

8 Ibid., September 9, 1886; September 13, 1886.

9 Sporting Life, July 14, 1886; September 22, 1886. It may have been that his pregnant young bride was yearning for his return.

10 Ibid., May 9, 1888.

11 The Sporting News, October 25, 1886; September 13, 1886.

12 Ibid., October 25, 1886.

13 Sporting Life, November 17, 1886.

14 Ibid., November 3, 1886.

15 The Sporting News, March 26, 1887.

16 Sporting Life, June 15, 1887.

17 Paul Hofmann, “Charlie Ferguson,” SABR BioProject.

18 The Sporting News, December 17, 1887; Sporting Life, November 2, 1887; November 9, 1887; November 23, 1887.

19 Ibid., March 28, 1888; April 4, 1888; April 18, 1888.

20 Philadelphia Inquirer, April 30, 1888.

21 Public Ledger, April 30, 1888; The Sporting News, May 9, 1888.

22 Ibid., May 5, 1888.

23 Sporting Life, May 16, 1888; March 28, 1896.

24 Ibid., September 29, 1888.

25 J. Casway, “Jimmy Fogarty and the Brotherhood Movement,” Nineteenth-Century Notes, Spring 2014, 1–2; Public Ledger, May 21, 1891; Sporting Life, May 23, 1891; “Jimmy Fogarty File,” Baseball Hall of Fame, undated clipping.

26 Sporting Life, November 17, 1886.

27 Ibid., December 14, 1886.

28 Ibid., October 6, 1886.

29 Ibid., November 10, 1886.

30 Ibid., November 3, 1886; November 12, 1886; November 24, 1886; December 1, 1886; December 8, 1886; December 29, 1886; The Sporting News, January 22, 1887.

31 Sporting Life, August 31, 1887.

32 Ibid., March 23, 1887.

33 Ibid., July 13, 1887.

34 Ibid., November 23, 1887.

35 The Sporting News, July 28, 1888; Sporting Life, August 1, 1888.

36 The Sporting News, May 22, 1889.

37 Sporting Life, July 10, 1889.

38 F. Lieb & S. Baumgartner, The Philadelphia Phillies, New York: Putnam, 1953, 32.

39 Sporting Life, April 3, 1889.

40 Philadelphia Inquirer, March 8, 1889.

41 Ibid., November 16, 1889; Spalding Guide, 1890, 11–26.

42 Philadelphia Inquirer, June 16, 1890. For details of Fogarty’s Brotherhood experience see J. Casway, “Jimmy Fogarty and the Brotherhood Movement,” Nineteenth-Century Notes, Spring 2014, 3–4.

43 Philadelphia Inquirer, August 24, 1890; September 7, 1890.

44 Ibid., December 26, 1890.

45 Public Ledger, May 21, 1891.