Baseball from Mars: The 1986 Super Major Series

This article was written by James Forr

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1960-2019

Telephone card souvenir from the 1986 Super Major Series (Robert Fitts Collection)

Opposing thoughts can complement one another and fill our lives with elegant contradictions. In ancient Chinese philosophy, this theory was known as yinyang. In Japan, the word is inyo.

Although frequently associated with Eastern thought, inyo is a universal part of the human experience. Any virtue can be a vice. There is no light without shadow. Love is the first cousin of hate.

By 1986, America’s visceral wartime animosity toward Japan had long receded. In its place bubbled a complex brew of fascination and fear. Inyo.

In September 1980, NBC aired a nine-hour miniseries called Shogun, an adaptation of a novel about an Englishman in feudal Japan. Shogun’s scenes of sexuality and violence were shocking for its day, and the show featured extended stretches of Japanese dialogue with no English subtitles. It was a weird choice for a prime-time network slot, and some executives feared it would be a disaster.

Instead, it was all anyone could talk about. Nearly one-third of all Americans watched Shogun, a cultural phenomenon that “spurred a faddish mania for all things Japanese.”1 Before long, sushi became mainstream in the United States, loyal communities of anime fans popped up out of nowhere, and the hoity-toity set grew enchanted with Kabuki theater and Japanese fashion.

Meanwhile, the term “Made in Japan” was taking on new meaning. For years, Americans had derided Japanese products as cheap crap doomed to fall apart five minutes after you left the store. However, by the mid-1980s, even if you weren’t scarfing down eel rolls or watching Star Blazers, you might have been driving a Honda, listening to music on a Sony Walkman, or replaying your favorite shows on a Panasonic VCR.

In contrast, US manufacturing was in decline, which wounded Americans’ national pride and inflamed insecurities about the nation’s economic future. While Japan was becoming cool, it was, at the same time, emerging as a bogeyman for those fears.

Democratic nominee Walter Mondale gave voice to this apprehension during his presidential campaign, asking a group of steelworkers in 1984, “What do we want our kids to do? Sweep up around the Japanese computers?”2 Conservative lawmakers called for boycotts.3 Frustrated autoworkers and other self-styled patriots got into the spirit by pulverizing Japanese cars with sledgehammers.4

Oddly, in certain ways, Americans held Japan in higher regard than Japan held itself. Inyo.

The searing humiliation of World War II still lingered in the folds of Japan’s collective memory, and a nagging sense of inferiority was never far from the surface. The country and its people felt a constant pressure to measure themselves, particularly against the West.

“I always felt Japan collectively was looking in the mirror saying, ‘Look at us!,’ and then looking around and asking, ‘How do we stack up?’” observed Michael Shapiro, who worked as a correspondent for the New York Times in Tokyo from 1984 to 1988.5

These conflicted feelings extended to baseball, where American and Japanese cultures had overlapped clumsily around the edges for decades. The Japanese considered American players to be, well, a little too American. In this highly collectivist culture, the gaijin from the West who joined Japanese teams often called attention to themselves in most unfortunate ways – berating umpires, criticizing managers, abusing equipment, and starting fights.

“There were stories about how gross American ballplayers were,” said Shapiro, who traveled with the Baltimore Orioles during their 1984 tour.6 He recalled the team bus rolling through crowded streets as one player exposed himself through the window, a pair of sunglasses perched on his penis and a cigarette tucked under his scrotum.

Americans might have been obnoxious, but in baseball they were the yardstick. So, with the revulsion came a certain hypnotic allure. Inyo.

Although television coverage of American baseball was sporadic, astute Japanese fans knew all about the stars of the US game and built them up into superheroes. American teams made goodwill visits of Japan every few years, but no team of big-name all-stars had made a tour to compete solely against the Japanese since 1953. Here was an opportunity.

On August 25, 1986, after 19 months of discussions, Baseball Commissioner Peter Ueberroth and Nippon Professional Baseball Commissioner Juhei Takeuchi announced that all-stars from both leagues would meet in a seven-game series in Japan November 1-9. It was dubbed in Japan the Super Major Series.

“Major-league baseball was trying to spread its wings,” remembered Boston’s Rich Gedman, one of the players selected. “For Japan, it was probably a measurement of where their game was at. For us, it was to give American baseball exposure to the world.”7

Really, though, it was less a measurement of the Japanese game as it was a measurement of the Japanese. Some of the best players in Nippon Professional Baseball were Americans, but when one of those expats, Leron Lee, asked to represent Japan, he was rebuffed. “No. Japanese only. Sorry.”8

Greg “Boomer” Wells received the same line. After being “sold like a slave” by the Minnesota Twins to the Hankyu Braves in 1983, Wells immediately established himself as one of Japan’s most fearsome sluggers.9 Yet, there was no room for him with the Japanese all-stars. “I would have loved to have played because I had something to prove, too,” Wells said.10

Wells believed his omission also was a lost symbolic opportunity, a missed chance to show the world a different face of the Japanese game. These newer American stars like Wells, Leron and Leon Lee, and Randy Bass weren’t cynical retreads trying to score one last baseball paycheck. They were young and skilled and they treated the game and the nation with respect.

“We were a part of Japanese baseball,” Wells insisted. “We were changing Japanese baseball and changing the way they thought of Americans. So we wanted to play. But they didn’t want that. They wanted to play them on their own. They wanted to prove something.”11

The US team consisted almost entirely of players who had been chosen for the 1986 All-Star Game in Houston. It wasn’t a tough sell. To travel to a new country and share a clubhouse with supremely talented peers was enticing. The money probably didn’t hurt, either. Each American received $30,000, plus all expenses paid for themselves and a companion.12

While coverage was limited in the States, the series was all over the front pages of Japan’s sports dailies. “Everything was about how great the majors were, but it was almost like they were from Mars,” joked Jim Allen, who was teaching English in Hamamatsu and who later became a journalist and statistical analyst specializing in Japanese baseball. “It was like the major leagues were a league meant for aliens. ‘We play baseball, they play baseball. But their baseball is different.’”13

“There was so much respect and reverence toward the major leaguers from the Japanese media, the fans, and even the players,” remembered Rob Smaal, who covered the series for the Japan Times. “It was like, ‘We’re going to get pounded by these guys, and it’s going to be an honor to get pounded by these guys.’ I was taken by the fact that it wasn’t, ‘Let’s go win this thing.’ It was more like, ‘Let’s watch these guys perform.’”14

But even when optimism is in short supply, there is always hope. After all, Japan had won a number of games against the two most recent major-league clubs to visit, the 1984 Orioles and the 1981 Kansas City Royals. Those weren’t all-star teams, of course, and the Americans spent half the time drunk or hungover, but still, wins are wins.

“The Japanese were practicing furiously,” according to Smaal. “It was important to them to perform well. They didn’t want to be embarrassed.”15

The Japanese team was mindful of the historic context of the event. “In the past we studied the Americans in baseball. Now we want to lead,” proclaimed Hiroshima Carp legend Koji Yamamoto, who at age 40 was making his final appearance as a player.16

Recently retired Yokohama Taiyo Whales manager Sadao Kondo, chosen to pilot the Japanese squad because he had been the eldest manager in NPB, offered a warning for the Americans. “If they think they are here for a sightseeing tour, they may be in for a shock.”17

US manager Davey Johnson made sure there was none of that. He, too, had something to prove. Johnson had just piloted the New York Mets to a World Series title. Now, only weeks after his greatest success, he was returning to the site of his greatest failure.

Johnson’s entire Japanese experience had been streaked with inyo. A three-time Gold Glove winner and four-time All-Star, Johnson left the Atlanta Braves to join the revered Yomiuri Giants as their starting third baseman in 1975. He wasn’t the first big-name major leaguer to sign with a Japanese team; however, for a prominent American to come over near the peak of his career, as Johnson did, was unheard of.

His arrival was both eagerly anticipated and deeply controversial. The Giants had won 10 pennants from 1963 to 1974, their “pure-blooded period” when they employed no foreign players at all. Many fans and even some players preferred it that way.

Johnson flopped – spectacularly. He struggled with the language and the culture and hit just .197. The Japanese press was brutal, dubbing him, “Dame Johnson,” which loosely translates to “No-good Johnson.” To boot, the Giants tumbled to last place.

Johnson rebounded in 1976 and helped the Giants rocket to a pennant, but he clashed with his manager, the legendary Shigeo Nagashima, and chose to return to the United States – not exactly in disgrace, but hardly awash in glory.

Ironically, unlike many gaijin, Johnson actually enjoyed Japan, which made his experience all the more painful. Ten years later, as he prepared for the Super Major Series, the wound still festered. As he told historian Robert Whiting, “I especially wanted to do well because of what had happened before.”18

Johnson was no authoritarian, but he implored his team to take the tour seriously. Indeed, players reportedly were chosen not only for their talent, but also for their professionalism. Fun would be had, but these particular guys weren’t going to drink themselves blind every night or spark any international incidents.

Johnson led his squad through two days of workouts at Dodger Stadium before chartering a 747 to Tokyo. According to Cal Ripken, “At the first team meeting, Davey said, ‘Let’s go over the signs. … Aw, the hell with it. Let’s not have any signs.

“‘And no take signals, either.

“‘On 3-0, you’re all swinging.

“‘Anytime you want to steal, then steal.’”19

The clubhouse roared at every line, but Johnson was serious. The way he saw it, the best strategy was no strategy. According to Washington Post columnist Thomas Boswell, Johnson’s experience in the country taught him he could rattle the Japanese by throwing the book out the window. Japan would play its way – traditional, disciplined, cautious. The Americans would swagger in and do whatever they darn well pleased.

“[Baseball officials] figured we weren’t taking it seriously enough,” said Ripken. “They were wrong. We played together great. Davey had jacked our confidence sky-high.”20

The US contingent arrived in Tokyo on October 30. Their hosts welcomed them with an imperial feast, complete with ornate ice sculptures; taiko drums; servers dressed as Geisha offering up sushi, Kobe beef, and other delicacies; and a bottomless well of desserts and alcohol.

“They really rolled out the red carpet,” marveled Smaal. “Reporters are generally slobs, walking around in T-shirts and jeans. They said, ‘Guys, please, jacket and tie required for this thing.’ What a festival they put on.”21

The next day both teams appeared for workouts at Tokyo’s venerable Korakuen Stadium, Johnson’s home ballpark when he was with the Giants and the site of the series’ opening two games. Michael Shapiro wrote in the New York Times that Johnson looked like “a man who, when his life is rosiest, happens to run into the high school flame who broke his heart.”22

He enjoyed a pleasant reunion with his erstwhile teammate, the great Sadaharu Oh, Yomiuri’s manager, who served as a coach for the Japanese all-stars. As the old friends exchanged pleasantries, Johnson turned to reporters and said, “He was the guy. I used to cry on his shoulder.” Oh replied wistfully, “Good things and bad things.”23

Texas Rangers reliever Greg Harris says the atmosphere was loose, but he and his teammates knew they had a job to do. They prepared almost the way they would have for regular-season games in the States. “It was a mindset of, ‘We’re representing the United States. We better be serious here.’ We didn’t want to lose.”24

The highlight of that first workout was batting practice. Japanese players stood slack-jawed as the Americans launched one ball after another deep into, and sometimes over, the bleachers. After Ripken ripped a drive to the base of the scoreboard, some 450 feet away, three-time NPB Triple Crown winner Hiromitsu Ochiai of the Lotte Orions could only shake his head. “Look at that,” he gasped. “Nobody in Japan could do that, not even me.”25

That spectacle replayed itself throughout the series. “The fans really enjoyed watching power hitters,” according to José Canseco, who reportedly cracked a seat with one of his interstellar pregame shots. “They really got into [batting practice] more than the game.”26

“The ballparks were really, really small and everything was going over the fence,” said Harris. “You’re shagging fly balls, but everything in the air was gone. You might as well have just sat in the stands.”27

Game 1 likely would not have been played in the United States. After ceremonies that featured the Japanese, American, and Canadian national anthems, a persistent drizzle transformed into a steady rain. Even though the grounds crew emerged multiple times to manicure the mound, US pitchers Teddy Higuera and Willie Hernandez each slipped repeatedly in the expanding quagmire. Johnson, alarmed, tried to get the game stopped, but the umpires were determined to squeeze in an official game, risk of injury be damned.

The rain limited attendance to a disappointing 34,600 but failed to dampen the crowd’s enthusiasm. Fans waved American flags, rattled plastic noisemakers, and bellowed fight songs and chants. That atmosphere was something new for the Americans, including California Angels pitcher Mike Witt.

“They had cheering sections and drums. It was almost like going to a football game. Constant noise and chatter.” Witt said.28

One recurring song, set to the Mickey Mouse Club theme, drove Cincinnati reliever John Franco to distraction. “I’ll probably fall asleep tonight with that same M-I-C-K-E-Y M-O-U-S-E tune ringing in my ears,” he quipped.29

Amid the din, the Americans took a quick first-inning lead when Ryne Sandberg drove a hanging slider from Yomiuri’s 16-game winner, Suguru Egawa, over the fence for the first run of the series. Moments later, Dale Murphy’s two-run blast made it 3-0.

In the bottom of the first, the Japanese readied themselves to face Mike Scott, who was an intriguing figure for fans like Shinichi Ota. “Until his visit,” Ota wrote, “the split-fingered fastball was not known in Japan.”30 Scott had just captured the National League Cy Young Award after winning 18 games and leading the Houston Astros to the NL West title.

Yoshihiko Takahashi opened the bottom of the first with a single, but Scott immediately picked him off. Japanese baserunning pratfalls became a leitmotif of the series. In those days of Astroturf infields across the major leagues, only the most audacious baserunners would put one foot outside the dirt cutout when taking a lead. Japanese runners, though, routinely took leads with both feet on the turf.

“It was like, ‘Is this for real?’” said Harris. “Their own pitchers had slow moves, so they were able to get back, but we knew what to do. We’d just pick them off left and right.”31

Then there was Tony Peña behind the plate. His arm was impressive even to Americans; for the Japanese, it was like science fiction. “He picked a runner off second base without standing,” marveled one fan, Hitoshi Morita. “The runner had been walking back to the base and suddenly the second baseman caught the ball and tagged him. It was amazing.”32

Japan cut the lead to 3-2 later in the first on run-scoring hits from Ochiai and Koji Akiyama. Scott’s mysterious split-fingered fastball proved not too perplexing, after all. “I guessed he might not have been carrying his Vaseline in Japan,” joked one fan, Takeyuki Inohiza, referring to Scott’s reputation for doctoring baseballs.33 Scott blamed the weather. “It was a little wet throwing off that mound. We’re not used to playing when it’s that slick.”34

In the fifth, third baseman Hiromichi Ishige flubbed Murphy’s two-out groundball, which allowed Peña and Tony Gwynn to score and made it 5-2. Meanwhile, Higuera took over for Scott in the middle three innings and allowed just two baserunners while striking out six.35

In the seventh, with the score 6-3, the umpires finally halted play and awarded the game to the Americans. In the press box, Japanese sportswriter Kenichi Haruda turned to a colleague and predicted, “I think this is going to be a bad series for us.”36

By the start of the second game, the skies had cleared and 47,000 packed into Korakuen. Yomiuri’s Hiromi Makihara pitched brilliantly in front of his home fans, striking out five and allowing one hit as Japan led, 2-0, heading into the sixth.

However, reliever Yutaka Ono immediately stumbled, with walks to Ozzie Smith and Jesse Barfield. Smith scored on a throwing error by the shortstop, Takahashi. Later, after a walk to Ripken, Glenn Davis launched a three-run homer to put the Americans up 4-2. “The pitcher that gave up the big home run to Davis had control problems,” said Johnson. “It looked like he was trying to throw too hard.”37

In the ninth, Barfield’s homer was the centerpiece of a five-run outburst, as the Americans prevailed, 9-2. US pitchers –Witt, Harris, Franco, and Jeff Reardon – combined to strike out 15.

“The first inning, I got my breaking ball hit consistently,” remembered Witt. “Then I figured out they were really late on the fastball and couldn’t get the gist of the speed and movement of it, so I went with that the rest of the time I was there.”38

“Their style of pitching over there is to spot it, mix it up, and throw off-speed stuff,” Witt said. “The way the hitters get out on their front foot with their hands back is more conducive to hitting breaking balls and off-speed stuff than fastballs.”39

To make it even tougher, series organizers were using a special baseball, one that was a bit lighter than the ball used in the United States but heavier than the one used in Japan. “Trying to hit those fastballs from the American pitchers feels like hitting a steel pipe,” moaned Ochiai. “When I hit the ball, I can feel the vibrations from the impact flow all the way back into my arms. There’s just no way we can beat that kind of pitching.”40

The venue shifted to Seibu Stadium, on the outskirts of Tokyo, for Game 3. Jack Morris, Rick Rhoden, and Hernandez combined on a three-hitter and Peña homered as the visiting stars won their third straight, 3-0, in a brisk 1 hour, 56 minutes.

The Americans lost one of their catchers during the game. Rich Gedman was warming up Rhoden in the bullpen without a mask when a forkball glanced off the tip of his mitt and shattered his cheekbone.

“It was kind of messy,” Gedman deadpanned. At the time, his wife was away on a shopping excursion arranged by the series organizers. “The wives had a great time, but mine didn’t, in particular, because she found out that I was traveling on a bullet train to get to her and fly home.”41

Sadao Kondo admitted that reality had landed hard. The Americans looked almost like the bulletproof giants that fans thought they were. “[W]e would like to win at least one game,” the skipper told reporters.42

Next, the teams trekked west to the port city of Fukuoka, on the southernmost island of Kyushu. The venue was Heiwadei Stadium, a historic park built in the shadow of the remnants of a seventeenth-century castle and known for its udon noodle soup. Before 27,000, the Americans hammered Japan, 13-3, on the strength of a 17-hit barrage that featured two home runs apiece from Barfield, Von Hayes, and José Canseco.

Johnson noted afterward that his hitters were “beginning to come around” after their post-regular-season layoff.43 Witt figured it was just a matter of time. Japanese pitching was simply overmatched. “They didn’t have anyone throwing 95 over there. Our guys knew they could always [be ready to] react to a breaking ball, knowing they could hit any fastball thrown at them.”44

For Game 5, the series zigzagged about 400 miles back east to Koshien Stadium, near Osaka. With two aboard and the game tied, 2-2, in the seventh inning, Frank White’s groundball devoured Yoshihiko Takahashi at third. Davis and Murphy scored, and the Americans led 4-2. As White told it, Takahashi “came running over to second base, shaking his hand, and shouted, ‘Too strong, too strong.’”45

But moments later, the Japanese pieced together three infield hits, two errors, a wild pitch, and a pair of bloop singles against Reardon, Montreal’s fireballing closer. With the score tied, 4-4, Fujio Tamura of the Nippon Ham Fighters flicked a two-run, bases-loaded single over White’s outstretched glove and into shallow right field for the go-ahead runs.

The US team got runners to the corners with no one out in the bottom of the eighth, but Hankyu’s Yoshinori Sato struck out Canseco, Davis, and White to snuff out the rally and preserve Japan’s 6-4 victory, its lone win of the series.

As they traversed the country, the Americans received what was, for most, their first exposure to Japanese culture. The most fascinating things were the minutiae of daily life, things most Japanese probably took for granted.

“I had never seen cabs that had automatic-open doors,” said Canseco. “They had this car there that looked like a go-cart with a box on it. It must have been maybe six feet long, at the most.”46

The shopping grabbed Greg Harris, specifically a trip to the towering Mizuno flagship store in Tokyo, where he was fitted for his first set of golf clubs. “Each floor was a sport. I had never seen anything like that. We could pick out what we wanted and they would pack it up and send it back.”47

What stood out in Witt’s memory was the traditional chabudai tables in restaurants. “The table we sat at was no more than 18 inches off the ground,” he chuckled. “I’m 6’7”. Mike Scott is about 6’3”. You got Rick Rhoden, Buddy Bell, José Canseco – all these big dudes trying to sit cross-legged, putting our legs under this table. It was not happening.”48

After the ornate welcome banquet, Rob Smaal, the reporter from the Japan Times, took Rhoden and Hayes to Tokyo’s fashionable Roppongi district, where the nightlife is always hopping. “[Hayes] was a super-nice guy. He was interested in seeing everything. I showed him my apartment, which was tiny. He’s like, ‘Wow, that’s impressive that you can live here.’ He wanted to take it all in.”49

Rhoden, not so much. “He was more like the typical American – ‘I can’t believe you’d live in this kind of squalor!’” Smaal said with a laugh.50

Yokohama Stadium, just south of Tokyo, hosted the sixth game, which was a snoozer. Hayes and Cal Ripken each homered twice as the US cruised, 15-3. A notable moment was the final home run for Koji Yamamoto, a stalwart in Hiroshima since 1969 and one of Japan’s premier power hitters, with 536 career home runs.

“I’ve enjoyed this series, seeing some of my old friends from the States,” Yamamoto reflected. “So, I’m swinging relaxed and the ball just made it into the stands.”51

One of those old friends was Ripken, who had toured Japan with the Orioles two years earlier. Ripken credited his offensive outburst to some pregame advice from Yamamoto. “[He] pointed out that my swing has changed since 1984.” Ripken was a well-known tinkerer, so that wasn’t surprising. However, Yamamoto had an idea. “He suggested I get out in front of the ball more. I tried it and it worked.”52

US Navy Lieutenant Commander Tom Gorsuch of Baltimore hollered, “Way to Go, Cal!” as Ripken rounded the bases after one of his home runs. Gorsuch was among hundreds of American service members in attendance at Game 6, many of whom were stationed at nearby naval installations at Atsugi and Yokosuka. “I’ve been suffering from withdrawal symptoms,” Gorsuch said. “I haven’t seen a big-league game in two years, and before that I’d seen at least one Orioles game every year for 25 years.”53

Petty Officer Mike Honeysett of Detroit secured autographs from the two hometown Tigers on the tour. “Morris and Hernandez all the way. They’re my boys.”54 Honeysett and his fellow petty officer, Bill Pearson, tried to get the wave going during the game and bellowed “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” at high volume. “I just love sports,” said Pearson. “We go to the Mirage Bowl, the Japan Bowl, anything that’s sports from the States, we go.”55

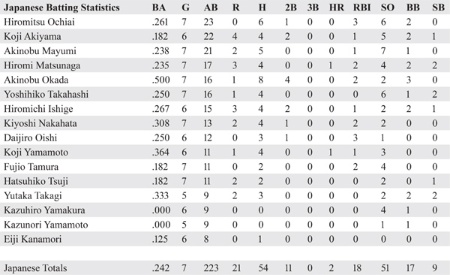

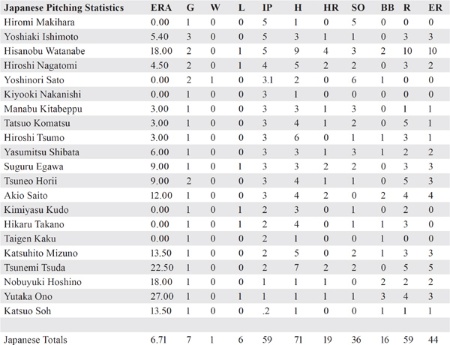

The series concluded back at Korakuen Stadium, where things ended as they had begun. Barfield, Peña, and Davis each homered to lead a 13-hit onslaught and Rhoden spun three-hit ball over five innings as the Americans swamped Japan, 9-4. The US team won six of the seven games, outhomering Japan 19-2 and outscoring them 59-21.

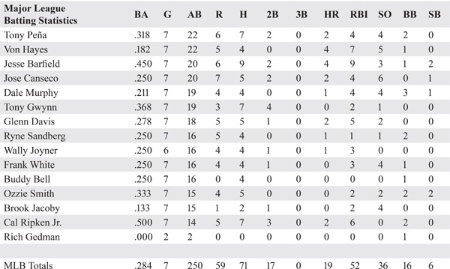

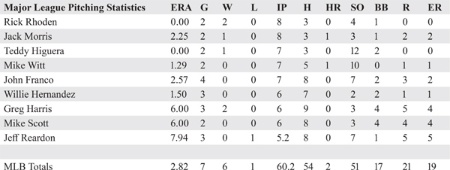

Peña batted .318, caught every inning after Gedman’s injury, and was named the American MVP. Several other players had magnificent tours, too. Ripken hit .500, while Barfield batted .450 with 4 home runs and 9 RBIs. Hayes hit only .182, but all four of his hits were home runs. Rhoden and Higuera combined for three victories and 15 scoreless innings. The Hanshin Tigers’ Akinobu Okada, who batted .500 (8-for-16), was named Japan’s MVP.56

Davey Johnson thought the quality of play in Japan had deteriorated over the preceding decade. “Guys like Sadaharu Oh, Shigeo Nagashima, and Koji Yamamoto stood head and shoulders above these guys.”57 Johnson speculated that if the Japanese all-star team played in a major-league division, they would finish .500 – at best.

Witt may have been even less impressed. He compared the quality of competition to what one would see in winter ball. “There were [the equivalent of] fringe major leaguers and really good Triple-A players. They were really skilled but did not have the physical prowess that we had.”58

Bob Brown of the Baltimore Orioles, who handled media relations for the series, was confounded. “As long as they’ve been playing the game so seriously, you’d think they’d be able to play us tougher now,” he said.59

The humbling results raised two questions for the Japanese – “What happened?” but also “Who cares?” Inyo.

Without question, the thorough wipeout was embarrassing. “It’s a mistake to think we can ever challenge the Americans,” said the Triple Crown winner Ochiai. “We’re like a team of Little Leaguers playing adults.”60

Nonetheless, although they looked at the series as an opportunity to measure themselves, and although the series suggested they didn’t measure up very well, the lords of the Japanese game almost seemed to pretend it hadn’t happened. Japan’s approach to baseball emphasized relentless drills and practice, risk-averse in-game strategies, and a rejection of weight-training methods common in the United States. Those philosophies did not shift easily.

“It gave them something to think about, but it really didn’t change anything,” according to Boomer Wells, who played in Japan until 1992. “It was sort of like if your team hasn’t won a game and you’re playing against the best team – you have nothing to lose, no pressure. That’s kind of how they took it.”61

Maybe it was also because the Japanese saw themselves as playing a fundamentally different game, one that was purer at its core. Kondo conceded the “big difference in speed and power” between his team and the Americans, but journalist Jim Allen argued that there was an unspoken ‘but’ at the end of that phrase.62

“That is a stock quote. In one way it is praise; in another way it is an insult,” Allen explained. “What the Japanese are telling you is, ‘They’re big and strong, but we play the game the right way. We work harder at the fine points of the game. We are craftsmen. They are just big, fast guys who play baseball.’”63 In other words, sizing up Japan against the Americans was a little like comparing Snoop Dogg and Stravinsky – fun and interesting, sure, but ultimately futile and kind of pointless. That’s how they rationalized it, at least.

Perhaps the series lacked any immediate overarching impact, but Sadaharu Oh later told Allen that it began to inspire some younger players who would make their names in the future. “Japanese baseball has narrowed the gap quite a bit for a number of reasons,” according to Allen, “but Oh credits a lot of that to the major-league tours of Japan.”64

In the coming years, those other reasons included the trailblazing efforts of Hideo Nomo and Ichiro, Japan’s victories in the World Baseball Classic, and increased television coverage of major-league baseball. But, true to the philosophy of inyo, the twenty-first-century triumphs of Japanese baseball may have taken root in the mire of one of its starkest defeats.

Acknowlegements

In addition to those individuals cited in the endnotes, the author wishes to thank the following people for their assistance: Kevin Glew, Paul Hensler, Brent Johnston, Yoshihiro Koda, Marty Kuehnert, Dave Ornauer, Alain Usereau, and Robert Whiting.

JAMES FORR dragged his non-baseball-fan wife to a Hiroshima Carp game on their honeymoon. Despite this, they remain married. His book Pie Traynor: A Baseball Biography, coauthored with David Proctor, was a nominee for the 2010 CASEY Award. James is also a winner of the McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award and has presented at the Frederick Ivor-Campbell 19th Century Base Ball Conference and the Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference.

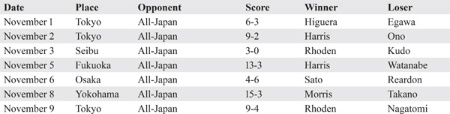

1986 All-Star Series Games (6 Wins, 1 Loss)

(Click images to enlarge)

Notes

1 David Kamp, The United States of Arugula: How We Became a Gourmet Nation (New York: Broadway Books, 2006), 316.

2 James Reston, “Washington; Mondale’s Tough Line,” New York Times, October 13, 1982: Sec. A, 31.

3 T.R. Reid, “Boycott Toshiba Computers, but Don’t Let Congress Force You,” Washington Post, July 13, 1987: WB11.

4 “Why Reward Failure in Detroit?” New York Times, March 5, 1981: A22; “Anti-Japan Sentiment Finds Ready Audience,” Chicago Tribune, February 26, 1992: D4.

5 Author interview with Michael Shapiro, November 9, 2021.

6 Shapiro interview.

7 Author interview with Rich Gedman, September 22, 2021.

8 Robert Whiting, You Gotta Have Wa (New York: Vintage Departures, 2009), 315.

9 Robert K. Fitts, Remembering Japanese Baseball: An Oral History of the Game (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), 152.

10 Author interview with Greg Wells, November 23, 2021.

11 Wells interview.

12 Davey Johnson received a reported $50,000 to manage the American team. “Mets,” Sporting News, October 13, 1986: 25.

13 Author interview with Jim Allen, October 19, 2021.

14 Author interview with Rob Smaal, October 26, 2021.

15 Smaal interview.

16 Daniel Sneider, “For Japanese, Playing Ball Against US Is More Than Just a Game. It’s a Chance to Beat US at One More Thing (Though They Didn’t),” Christian Science Monitor, December 9, 1986, https://www.csmonitor.com/1986/1209/obase.html.

17 Sneider.

18 Whiting, 316.

19 Thomas Boswell, “Davey Johnson Is a Semi-Changed Man. He’s Still Tough, Smart, and Relentless. But the Orioles’ Manager Has Learned to Manage the Politics of Baseball, Too,” Washington Post, March 31, 1996: 11.

20 Boswell.

21 Smaal interview.

22 Michael Shapiro, “Johnson Gets Warm Welcome in Japan,” New York Times, November 3, 1986: Sec. C, 2.

23 Shapiro.

24 Author interview with Greg Harris, August 26, 2021.

25 Ronald E. Yates, “Awed Japanese Bow to U.S. Stars,” Chicago Tribune, November 16, 1986: C12.

26 “Radio Baseball Cards: Jose Canseco on the 1986 MLB Tour of Japan,” https://www.spreaker.com/user/smarterpodcasts/rbc1919-josecanseco.

27 Harris interview.

28 Author interview with Mike Witt, September 27, 2021.

29 Jim Armstrong, “The Weather Puts a Damper on Opener,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 3, 1986: 26.

30 Author email interview with Shinichi Ota, translated by Yoshihiro Koda, October 21, 2021.

31 Harris interview.

32 Author email interview with Hitoshi Morita, translated by Yoshihiro Koda, October 21, 2021.

33 Author email interview with Takeyuki Inohiza, translated by Yoshihiro Koda, October 21, 2021.

34 Fujiyoshi Tamura, “U.S. All Stars Win Series Opener,” Japan Times, November 2, 1986: 13.

35 Japanese fans knew a little about Higuera. As a rookie, he was the breakout spring-training star of the Milwaukee Brewers in 1985. That happened to be the year 30 Japanese reporters descended on the Brewers camp to document the travails of hard-drinking, chain-smoking pachinko addict Yutaka Enatsu, who made an unsuccessful bid to win a spot in the Milwaukee bullpen. (Author email interview with Takashi Shinoura, translated by Yoshihiro Koda, October 21, 2021.)

36 Yates.

37 Fujiyoshi Tamura, “All-Stars Overpower Japan,” Japan Times, November 3, 1986: 13.

38 Witt interview.

39 Witt interview.

40 Yates.

41 Gedman interview.

42 Associated Press, “U.S. Major League All-Stars Top Japan,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, November 4, 1986: 10B.

43 “Barfield, U.S. Stars Pound Japan 13-3; Eye Clean Sweep,” Japan Times, November 6, 1986: 13.

44 Witt interview.

45 Sid Bordman, “California Girls Bolster Tennis Field,” Kansas City Star, November 25, 1986: 2B.

46 “Radio Baseball Cards: Jose Canseco on the 1986 MLB Tour of Japan.”

47 Harris interview.

48 Witt interview.

49 Smaal interview.

50 Smaal interview.

51 Sneider.

52 “Major Leaguers Rout Japanese,” Japan Times, November 9, 1986: 14.

53 Dave Ornauer, “All-Stars Treat Baseball-Starved Fans,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 13, 1986: 24.

54 Ornauer.

55 Ornauer.

56 Wayne Graczyk, 1987 Japan Pro Baseball Fan Handbook (Tokyo: Fan Te-cho Co., Ltd., 1987), 48-50.

57 Yates.

58 Witt interview.

59 Bob Maisel, “Stars Show U.S. Still Leads Japan in One Product,” Baltimore Sun, November 22, 1986: 1B, 12B.

60 Whiting, 315.

61 Wells interview.

62 Associated Press, “U.S. Clinches Major Series Finale,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 11, 1986: 26.

63 Allen interview.

64 Allen interview.

65 These tables include all participants in the series. Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs, U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 105; Nippon Professional Baseball Records, https://www.2689web.com/nb.html; Graczyk.