Baseball Geography and Transportation

This article was written by Alex Reisner

This article was published in 2006 Baseball Research Journal

In 1876, at the time of the National League’s inception, the only reasonable way for a baseball team to travel from New York (home of the Mutuals) to St. Louis (home of the Brown Stockings) on a regular basis was by train. Stagecoach was too slow. Buses, and roads good enough to support them, were over half a century away, and jet airplanes over three-quarters. Major league baseball teams therefore relied almost exclusively on the railroad for nearly 80 years.

The “travel day” between series, which today often amounts to a day off, was quite necessary in the era of rail transportation. At the turn of the century it took over 20 hours to go between New York and Chicago, and well over 24 between New York and St. Louis. These trips would usually be avoided by strategic scheduling, but even a short run like New York City to Buffalo took longer than seven hours.

But the change from rail to air and the proliferation of the automobile have affected far more than how the players get around. New modes of transportation have influenced the shape of the field of play itself and made possible one of the most heart-wrenching moves in baseball franchise history.

Jet Airplanes, Player Culture, and a transplanted rivalry

On June 8, 1934, Cincinnati GM Larry MacPhail flew 19 of his players to Chicago for a series with the Cubs,1 making the Reds the first team to travel by airplane. A dozen years later the Yankees became the first team to do it on a regular basis, chartering a Douglas DC-4 dubbed the “Yankee Mainliner” in the 1946 season.2

Still, airplane travel was far from a regular occurrence until the 1950s when jet engine technology made traveling longer distances faster, cheaper, and more comfortable. The 1950s also saw the birth of the Interstate Highway System (though a rudimentary system of transcontinental roads had been in place since the 1920s).

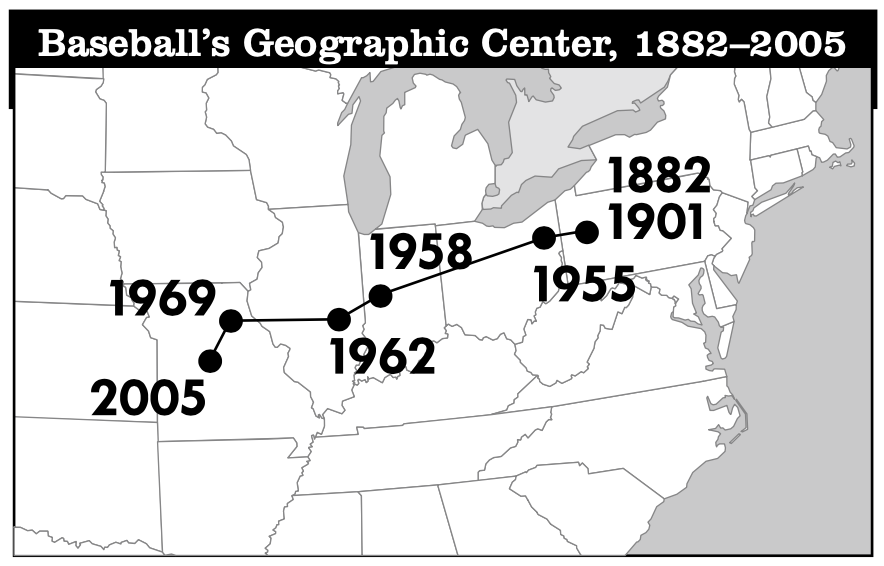

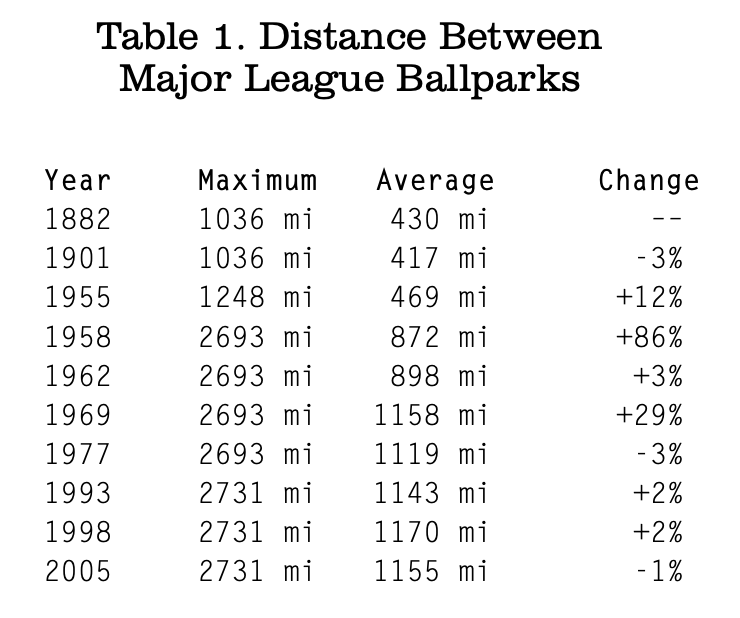

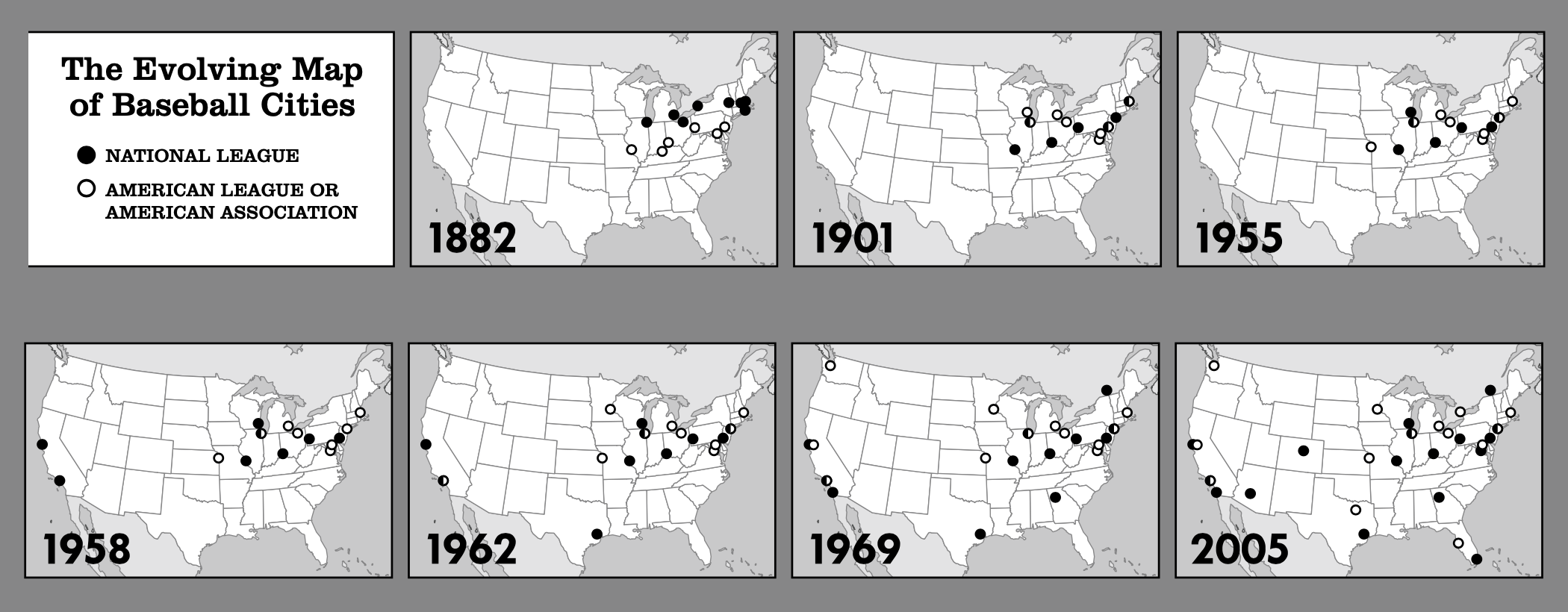

The increased mobility of the general population gave real estate businessman and Brooklyn Dodger owner Walter O’Malley the opportunity to move both his team and their crosstown rivals, the New York Giants, to California after the 1957 season. Prior to this move no team had been west of Kansas City, and baseball’s geographical center was near the Pennsylvania-Ohio border, relatively unchanged since 1876. All teams were within a day’s train ride of each other. O’Malley’s move shifted the center nearly as far west as Chicago and almost doubled the distance of the average commute between parks.

What else changed in the shift from rail to air? Don Zimmer, who played for the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1950s, relates: “On trains, we were together. You get on a plane, and you’re only talking to one person—the guy next to you. There isn’t the closeness now that there was then. We’d eat in the same dining car, we were always together. I’m not saying it was better, that was just the biggest difference.”3

Relations with the media were different, too. “The lives of the baseball players and the writers who covered them were interwoven, since travel by train, not plane, created situations in which avoidance was difficult, if not impossible.”4

Finally, relationships with fans became more distant. “Train travel had facilitated a traditional practice of whistle-stop barnstorming at the end of spring training, as teams would often make several stops along the way home from Florida or Arizona, playing additional exhibition games and/or making publicity appearances. Plane travel helped phase out this custom in the 1950s.”5

The Automobile, Suburbs, and Ballpark Symmetry

Professional baseball teams must play in places where fans can go to see them. Before the 1950s this meant that they played in cities, where the population was dense and public transportation available. In the 1950s, however, as cars became affordable and good roads the rule rather than the exception, the growing class of car owners began to move to the suburbs. It was no longer necessary to locate a ballpark in the city, and it became common practice to build on the outskirts, where land was cheaper, parking safer, zoning rules more lax, and events generally less disruptive.

The move to open sites has had profound effects on ballpark design. Most parks built in the 1960s and 1970s (Candlestick Park, Dodger Stadium, Shea Stadium, Olympic Stadium, San Diego Stadium, Astrodome, Kauffman Stadium, etc.) are round structures with symmetrical field layouts. Since they are located on the outskirts of their respective towns, the architects weren’t concerned with keeping the buildings within the bounds of city streets (for example, Lansdowne in Boston or Sullivan and McKeever in Brooklyn). Rather, without restrictions on shape or size they constructed symmetrical fields circumscribed by high, raked seating that placed fans farther from the action.

What does the future hold? While baseball used to go where the life was, some recent ballparks have been situated such that they bring life where it is needed or desired in sleepy downtown areas. Can we expect to see this trend continue? Baseball in Canada has not been a great success, but what about Mexico? Latin America? Japan? With frequent and inexpensive flights, the increasing number of MLB players coming from other countries and the advent of the World Baseball Classic, such ideas begin to sound distinctly plausible.

ALEX REISNER is a freelance computer programmer who enjoys music, photography, design, bicycling, the Marx brothers, playing, watching, and thinking about baseball.

Notes

1. “Cincinnati Reds Will Fly Here For Cub Series.” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 7, 1934: 23.

2. “Yankees’ Plane Is in St. Louis.” New York Times, May 14, 1946: 33.

3. Newman, Mark. “Finding ways to get to 100 Series.” MLB.com. September 21, 2003. Viewed January 24, 2006. http://mlb.mlb.com/NASApp/mlb/mlb/news/mlb_news.jsp?ymd=20030921&content_id=537248&vkey=news_mlb&fext=.jsp

4. Friend, Harold. “Joe DiMaggio: It’s None of Your Business.” BaseballLibrary.com. March 6, 2002. Viewed January 24, 2006. http://www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/submit/Friend_Harold7.stm

5. Treder, Steve. “Dig the 1950s.” The Hardball Times. March 23, 2004. Viewed January 24, 2006. http://www.hardballtimes.com/main/printarticle/dig_the_1950s/