Baseball’s Forgotten Era: The ’80s

This article was written by Dan D’Addona

This article was published in Fall 2011 Baseball Research Journal

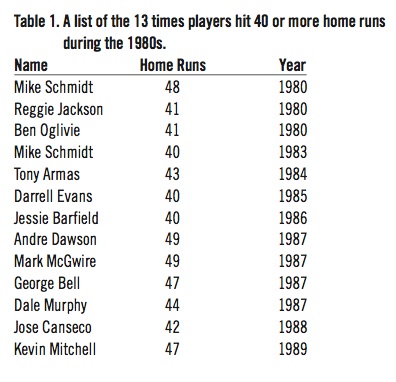

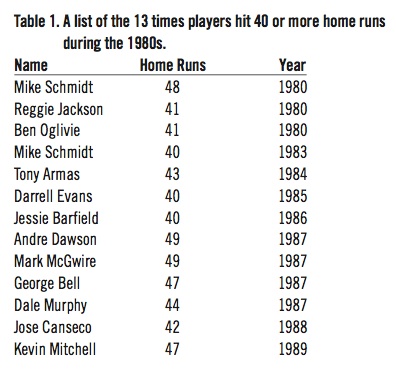

The 1980s was a decade of transition for baseball. Power numbers were noticeably down, making the eye-opening numbers of the steroid-enhanced decades following look even gaudier. The lack of power is just one of the many reasons the 1980s remains an overlooked era.The 1980s was a decade of transition for baseball. Power numbers were noticeably down, making the eye-opening numbers of the steroid-enhanced decades following look even gaudier. In the 1980s, players hit 40 home runs just 13 times—the lowest of any decade since Babe Ruth revolutionized the game.

The lack of power is just one of the many reasons the 1980s remains an overlooked era. Few things are celebrated from the 1980s, and much of what is remembered is negative: the 1981 strike, a cocaine scandal, umpire Don Denkinger’s blown call in the 1985 World Series, the banishment of all-time hits leader Pete Rose for gambling, an earthquake postponing the 1989 World Series, the spread of Astroturf.

But there were many great players and moments during the decade, they just weren’t reliant on the home run or recognized by the press. The superstars stayed out of the limelight as the game began to revolve around speed and relief pitching.

“The game is cyclical by its nature,” Major League Baseball Official Historian John Thorn said. “That is the biggest reason for minor swings in the ’80s.”

Baseball had plenty of cycles prior to the 1980s. Pitching became the dominant force in the 1960s, leading to significantly lower earned run averages and batting averages. But home run hitters continued to power the ball out of the ballpark in the 1960s and 1970s with plenty of 40 home run seasons from players like Hank Aaron, Mickey Mantle, Harmon Killebrew, Willie Mays, and Willie McCovey.

That cycle continued until the 1980s, when the home run totals of the game’s best sluggers returned to the 30s, only reaching the 40s 13 times. Philadelphia Phillies third baseman Mike Schmidt was the only one to do it twice, hitting 48 home runs in 1980 and 40 home runs in 1983. Reggie Jackson and Ben Oglivie each hit 41 home runs in 1980, Tony Armas slammed 43 in 1984, while Darrell Evans and Jessie Barfield reached 40 home runs in 1985 and 1986, respectively. 1987 may have been a harbinger of the decade to come, with four players topping 40: Andre Dawson and Mark McGwire each clubbed 49 homers, leading Dawson to the National League MVP and McGwire to the American League Rookie of the Year. Dale Murphy (44) and George Bell (47) also reached the feat in 1987 and Bell won the American League MVP. Oakland’s Jose Canseco hit 42 in 1988 and San Francisco’s Kevin Mitchell hit 47 in 1989 earning both players MVP trophies.

Compared to the previous and following decades, the ’80s appears to be a trough in individual power numbers. Players hit 40 or more home runs 20 times in the 1970s with Willie Stargell, Johnny Bench, and George Foster reaching the total twice. Sluggers reached 40 home runs a stunning 77 times in the 1990s and 91 times in the 2000s as steroids and smaller ballparks came to dominate the game. Elsewhere in this journal Jim Albert’s graphical representations of “the SABR Era” demonstrate drops in home run hitting in both leagues in the 1980s, in the latter half of the decade especially. When OPS is graphed from 1920 to the present, the only other decade showing a trough in power production similar to the 1980s is the 1940s, when war drained talent from the major leagues.

In 1990, Cecil Fielder hit 51 home runs—the first of three consecutive 40 home run seasons for the Detroit Tigers’ first baseman. That broke the longest streak of seasons without a 50 home run hitter at 13 years. Cubs second baseman Ryne Sandberg led the National League with 40. Canseco tied Fielder for the league lead with 44 in 1991. This started a decade in which at least two players hit 40 home runs every season. The first big surge happened in 1996 where 16 players hit 40 or more home runs.

Oglivie, the former All-Star left fielder for the Milwaukee Brewers, said it wasn’t the way sluggers in past decades approached hitting. “The long ball has become the thing to be enamored with, even with guys who can’t do it. The home run is pretty much a mistake thing. Pitchers don’t want to give up the home run. It is a glorified hit. It isn’t the goal to shoot for in this game. It happens when the guys are fundamentally doing the right things. It is almost like winning the lottery. The hitter wins the lottery when a pitcher makes a mistake. Nobody can go up and hit home runs every at bat.”

Oglivie, the former All-Star left fielder for the Milwaukee Brewers, said it wasn’t the way sluggers in past decades approached hitting. “The long ball has become the thing to be enamored with, even with guys who can’t do it. The home run is pretty much a mistake thing. Pitchers don’t want to give up the home run. It is a glorified hit. It isn’t the goal to shoot for in this game. It happens when the guys are fundamentally doing the right things. It is almost like winning the lottery. The hitter wins the lottery when a pitcher makes a mistake. Nobody can go up and hit home runs every at bat.”

And many players tried to swing for power less in the 1980s, especially with Astroturf taking up half of the ballparks. Teams like the St. Louis Cardinals began to change their lineups to focus on speed. The Cardinals ran with Ozzie Smith, Willie McGee, Lonnie Smith, and Vince Coleman, piling up stolen bases and winning three pennants behind manager Whitey Herzog. The style of play was dubbed “Whitey Ball.” But other teams were on the same track. Tim Raines and Andre Dawson both stole hundreds of bases for the Montreal Expos, while Tony Gwynn and Alan Wiggins ran free in San Diego. Across baseball, players stole more than 3,000 bases every year in the 1980s except strike-shortened 1981, something that had only been done nine other seasons in the modern era.

“Scoring runs is the name of the game [no matter how you get them],” Oglivie said. “So if you are drafting guys who can run, it makes a lot of sense. It was geared toward speed.” And once a handful of teams found that success, it wasn’t long before other teams began focusing on speed.

“There is an element of follow the leader that happened in the 1980s,” Thorn said. “The Yankees remade their roster in the 1980s to utilize speed and defense. And it didn’t work with that short porch.” Other teams out-slugged the Yankees in their home ball park, which was part of the reason the Yankees didn’t win a pennant after 1981 when their late-1970s dynasty began to break up.

Another major factor in low scoring was the rise of relief pitching and the role of the closer. The role emerged in the 1970s with guys like Rollie Fingers and Goose Gossage, but spread during the 1980s where most teams had a dominant closer. Fingers won the American League Cy Young in 1981. Bruce Sutter dominated for the Cubs and Cardinals. Gossage was still a force, and Willie Hernandez, Mark Davis, and Steve Bedrosian all won Cy Young awards as closers during the 1980s. Lee Smith, Dennis Eckersley, and Dan Quisenberry began to befuddle hitters. It was the first decade in which closers across baseball basically took an inning away from opposing offenses. Coming into the decade, there were only seven seasons in which 20 percent of the games had saves recorded and 71 seasons with less than 10 percent of the games having a save. But every season in the 1980s had more than 20 percent and that trend has continued to the present.

“Relief pitching patterns changed,” Thorn said. “Sutter and Gossage continued to dominate, but Tony La Russa started using Eckersley in the ninth inning. I think anyone could have had a good closer any time they wished.”

The onslaught of relief pitching had a direct effect on the hitters in the 1980s, Oglivie said, especially the power numbers. “Now, they don’t face the starters as long. When I played, we might see a starter the whole game. Baseball is evolving. It was tougher for the hitters in that way.” He went on to explain, “Now, starters pitch five, six, or seven innings. It gave the hitters time to make the adjustments. If you had faced a pitcher one or two times around, usually by the third time, you have a bead on that pitcher. Now, someone comes in in the sixth inning and he can pitch in the high 90s. Good pitchers, you might see them a fourth time, but three times is a lot today. After the third time, you have a new pitcher and it is like you start over again. And you see a closer one time.”

Another thing teams saw only one time in the 1980s was a World Series title. Nine different teams won World Series championships during the decade, a vast difference from having just one team win only a single series in the 1970s. Oakland, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and the New York Yankees all won multiple championships while Baltimore just won in 1970, (though they did have pennants in 1971 and 1979). National television audiences got to know many of the players who were in multiple World Series. And the Yankees finally picked it up again in the 1990s, winning four titles in a five-year period letting the nation become acquainted with players like Derek Jeter and Mariano Rivera.

“The lack of a dynasty may be a testament to free agency,” Thorn said. “That continued in the 1990s. For all the talk in the late 1970s of how free agency was going to kill competitive balance, the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s had a greater balance than ever before.”

The spread success also came from the team-first attitude of the superstars of the game. While outspoken Reggie Jackson was winding down his career, quiet superstars like Cal Ripken Jr., Robin Yount, Tony Gwynn, Ryne Sandberg, Dale Murphy, Eddie Murray, Ozzie Smith, and Andre Dawson emerged. All were great, but perhaps Ripken is the only household name of the group. Mike Schmidt and George Brett were perhaps the best players of the decade but their names do not resonate in the mainstream like the names of the previous era of Aaron, Mays, Mantle, and Clemente.

“The 1970s were kind of flamboyant,” Thorn said. “You had the afro hairdos, the disco demolition. It is not a surprise that it leveled off [in the 1980s].”

That was the way the stars of most teams acted, Oglivie said. “Robin Yount was not the type of guy to talk,” he said. “There is something about quiet leadership. He didn’t have to be loud to get his point across. Your point can be made with how you perform on the field. Reggie Jackson said what he had to say, and that was his game, and that’s fine. Our team didn’t have that. Yount led by example, Molitor the same thing, but he was a little more outspoken than Robin was. Language is expressed a lot more by what they do than what they say.”

The next era, home runs became the expression and that led to more household names like Ken Griffey Jr., Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire, and Sammy Sosa. Power hitters returned to the limelight for their feats on the field and, eventually, the controversies off the field.

The cyclical nature of the game continued, Thorn explained. “When power numbers are down (for a while), there is only one place for them to go.”

The change was inevitable, but Oglivie doesn’t like the effect the big numbers have had on younger hitters. “I have a different perception when it comes to the long ball,” said Oglivie, who is the hitting coach for the West Michigan Whitecaps, a Class-A affiliate of the Detroit Tigers. “When you look at baseball today, the guy from the first to the last in the lineup wants to hit a home run. They want to go for the long ball. During the era of Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays, the fourth and fifth hitter was looked upon as the ones to hit home runs. The first and second guys set the table. Now, everyone works to hit home runs at the expense of their average even if it is something they can’t do effectively throughout the season. You see a lot of fly ball outs.

“You can have second hitters hitting 20 or 30 home runs. In the past, it wasn’t that way. It is not something players should try for if that’s not what their cup of tea is.

“They lose the sense of what they are supposed to accomplish for the team.”

But the good players of each era would thrive in any era, Oglivie said. “Mike Schmidt and Reggie Jackson would still get their home runs today,” he said. “The game hasn’t changed. The lines and dimensions haven’t changed. The eras are different.”

And, sandwiched between baseball’s Golden Era and the Steroid Era, the 1980s will continue to be overlooked.

DAN D’ADDONA has been a SABR member since 2005. He worked at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and is an award-winning writer for “The Holland Sentinel”. He has covered championships for the West Michigan Whitecaps and Detroit Tigers. He is currently working on a book titled “In Cobb’s Shadow: The Forgotten Careers of Crawford, Heilmann, and Manush”.

Sources

- Stats from Baseball-Reference.com and Baseball-Almanac.com.

- John Thorn, telephone interview, 16 May, 2011.

- Ben Oglivie, interview, 5 June, 2011.