Baseball’s Most Unbreakable Records: Polled from SABR’s Records Committee

This article was written by Joe Dittmar

This article was published in 2002 Baseball Research Journal

More than any other sport, baseball as we know it today is infatuated with numbers. Every movement, whether from defensive positions, the pitcher’s mound, or the batter’s box, is examined, analyzed, and quantified. As a result, we are treated to “quality starts,” “holds,” and batting averages with two-strike counts or on artificial turf in night games. Statistics not even dreamed of 50 years ago may now be woven into player contracts or even influence managerial decisions. Computers allow us to analyze not only current performances by way of intricate mathematical formulas, but also to resurrect and compare those of more than a century earlier. Spawned by this fascination with records, those best-worst, longest-shortest, most-least measurements now engorge a multitude of books and test the wits of ardent fans.

The national pastime is unique in that its daily meanderings have been recorded with surprising consistency since 1871, when the first professional league was born. The 19th century brought formation and self-realization for the professionals, and as such precipitated endless tinkering with the rules. The resulting rampant rule changes make comparison with 2oth century performances a conundrum. Can we fairly compare strikeouts by pitchers throwing under-handed or from a distance of 50 feet with those of today’s hurlers? During 1880, Providence’s George Bradley issued only six free passes in 196 innings pitched. At the time, however, eight balls were required for a walk.

Performance expectation was also shockingly different in baseball’s adolescence. Substitutions were rare, pitchers were expected to complete games regardless of the number of innings, and players often competed despite injuries. Such was the case in 1877, when Louisville’s Jim Devlin pitched every inning (559) of every one of his team’s games.

In addition, equipment and playing arenas make comparison difficult. Is it reasonable to compare the spongy, blackened baseballs being hit to bare-handed fielders with the projectiles currently being served to the plate? Ballparks with distant outfield limits were once commonplace, as were fans lining playing perimeters. And what may now be bemoaned as fan interference was often accepted as simply another dimension of the early game.

These variables should be considered while making any pronouncement of the most or least of any aspect of the game. Nevertheless, it is exactly because of these significant differences that we marvel at statistics of bygone eras. And when many of those record-setting statistics are taken out of context and placed in today’s atmosphere, they do indeed appear unfathomable and unbreakable.

For all of the reasons mentioned above, most of the records considered in this treatment were of a 20th-century nature, or at least subsequent to 1893, when staffs were hurling overhand and from a distance of 60 feet, 6 inches. A few exceptions were tolerated, such as the fact

that the venerable Cy Young won 72 of his games and tossed more than a thousand innings at a distance less than the current one. But for the most part, bench marks established prior to 1893 are beyond the scope of this analysis.

Just what records, then, are unbreakable? The lists accumulated from members of the SABR Records Committee range from the familiar to the esoteric, from Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak to Connie Mack’s seven consecutive eighth-place finishes. Most remarkable was the sheer number of records considered by members to be unbreakable. Initial polling revealed several dozen marks, but as more lists rolled in, new depths in obscurity were probed, resulting in more than a hundred benchmarks that may be considered safe from the ravages of future challenges. For the sake of space, and sanity of the tabulator, an attempt was made to limit the listing to generally accepted and understood categories.

Following are lists of standards that members considered unbreakable, divided into ten very general categories. While most records result from a combination of circumstances, these were the major factors:

- Performance expectations

- Scoring/playing rules

- League structure/rules

- Ballpark configurations

- Tightened crowd control

- Equipment

- Game strategy

- Outside influences

- Outright superb performance

- Alignment of the stars

DIFFERENT PERFORMANCE EXPECTATIONS

This was the largest category of untouchable records submitted by committee members. Most were established in an era so different from today, they strain the limits of credulity. We can only shake our heads and marvel at the litany of numbers left by Cy Young—games started, games won and lost, complete games, innings pitched, and batters faced. Less well known but equally staggering are the marks of Jack Taylor, who labored 1,727 consecutive innings, including 187 complete games, without being relieved; of Joe McGinnity, who tossed five complete doubleheaders in his career; or of pitchers Leon Cadore and Joe Oeschger, who each went the distance in a fabled 26-inning marathon. Two Boston clubs, 1901 NL and 1904 AL, went the entire season while employing just five moundsmen.

Today’s hurlers, asked to throw hard for as long as they can, and who anticipate relief when their fastballs lose five miles per hour off the radar gun, simply are not expected to approach the stamina limits of their predecessors. The availability of relievers and concern for injury, as well as career length, earning potential, and long-term contracts all limit the efforts of the modern-day hurler.

While most benchmarks relative to performance expectations concern pitching accomplishments, not all of them are positive. During the first several decades of the century, even when pitchers were underperforming, they were expected to remain in the fray and “take their medicine.” Thus Dolly Gray bore the ignominy of issuing a record seven consecutive walks, and Eddie Rommel was once shelled for 29 hits in a single game.

CHANGES IN SCORING/PLAYING RULES

Rule changes made throughout the century provide safe harbor for many previously established “records.” For example, pinch-hitters can no longer be credited with two pinch hits in the same inning as they once were. There are many of these instances in the books, but a rule instituted in the 1950s precluded a player from pinch-hitting for himself if he stepped to the plate a second time in the same inning. A second at-bat by the same pinch hitter now is considered as that player batting for himself, not for another player.

Another rule change, one of defensive indifference, will likely keep safe the mark shared by the Senators of 1915 and the Phillies of 1919. Each club stole eight bases in one inning, the Nationals doing it in the first inning against sore-armed Cleveland catcher Steve O’Neill, and the Phillies notching eight in the ninth inning of a lost game. The rule was changed in 1920.

CHANGES IN LEAGUE STRUCTURE/RULES

Early in the 20th century most clubs employed very few players. The entire roster of the 1904 Boston American League club contained the names of only 18 players, five of the1n pitchers. The five moundsmen remain the minimum mark.

BALLPARK CONFIGURATIONS

When the Pittsburgh Pirates set their 20th-century team record of 129 triples in 1912, they played half their games in cavernous Forbes Field. There the distant outfield limits measured LF 365′, RF 376′, CF 435′, and were well suited for circling the bases on line drives. The biggest contributor that season was Owen “Chief” Wilson with 36. His single-season record, however, may more suitably belong in the category of “Alignment of the Stars,” since his second best campaign netted just 14 three-baggers.

Fielding records, too, were influenced by ballpark dimensions. Chuck Klein’s 44 outfield assists in 1930 were not only the result of his fine arm but also the towering wall in right field just 280′ from home plate. Even right-center was a scant 300′ from the batters, affording ample opportunities for playing caroms and nipping frisky baserunners.

Finally, the advent of lights in stadiums locked forever the mark of 1o tied games by the Detroit Tigers in 1904.

TIGHTENED CROWD CONTROL

On July 12, 1931, the Cubs invaded St. Louis, and Cardinal fans turned out in record numbers. So many attended, in fact, that they spilled from the stands onto the field, reducing the playing dimensions to schoolboy proportions. Police were woefully outmatched as fans collected souvenirs on routine fly balls hit to the outfield. This necessitated a hastily made rule of the day considering as a double any ball hit into the crowd. Although a doubleheader was played, the second game alone produced 23 doubles, another mark that likely will stand the test of time.

CHANGES IN EQUIPMENT

No doubt the size and shape of modern baseball gloves has altered fielding averages. But perhaps the most pronounced impact on records has been dealt by the constitution of the ball. The dead ball era was so called because of the softness of the ball, which in turn influenced strategy. Runs were scored one at a time, and home runs were uncommon. The dead ball put the advantage into the hands of the men who stood on the mound. Sacrifices also held great importance, ERAs collapsed, and shutouts were more common than in today’s game. During this era Grover Alexander garnered 16 shutouts in a single season, and Ray Chapman collected 67 sacrifices, both marks that still stand.

CHANGES IN GAME STRATEGY

Changes in the liveliness of the ball also fostered corresponding alterations in straegy. John McGraw’s gritty management style in the dead ball era fostered an abundance of stolen bases. The Giants of 1911 still retain the modern single-season team stolen-base record of 347, the same year the Yankees stole 15 in one game. Ten years later, with the advent of the live ball and the spectacular impact of the home run, the Giants, still under McGraw, stole only 137 bases. Strategy was more blunt that year as Ruth amassed an astonishing 457 total bases, still the all-time benchmark.

Today’s infatuation with power hitters and the home run has encouraged more players to swing for the fences. Recently we’ve seen one of the game’s most glamorous records, Roger Maris’s 61 home runs, buried beneath a barrage of long ball clouting. But this environment has also enabled quality pitchers to take advantage of the free swinging, and thus we marvel at the inconceivable 5,714 lifetime strikeouts by Nolan Ryan. This unbreakable record appeared on most lists submitted by Record Committee members.

OUTSIDE INFLUENCES

The strength of the players union will undoubtedly keep safe many records of the past. Coupled with owners’ financial considerations, it is doubtful we will ever again witness the 44 doubleheaders played by the White Sox in 1943; the nine consecutive doubleheaders played by the Boston Braves in 1928; or the tripleheader (three complete games) played in one day on three occasions.

Before radio and television imposed their demands on game times, play was generally more brisk. Astonishing in today’s context is the safe record of the nine-inning game played in only 51 minutes between the Phillies and Giants in 1919.

OUTRIGHT SUPERB PERFORMANCES

As noted, few records can be attributed to a single reason, but some are the result of a singular performance by an exceptional player. Although a little luck can’t be ruled out, and the lack of dominant relievers helped, Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak made the “unbreakable” list of most Records Committee members. In the same category would be Ruth’s lifetime slugging average. These accomplishments are so far beyond the runner-up as to render them in the unbreakable category.

Also included in superb performances would be the .440 batting average by Hugh Duffy, Hornsby’s .402 five-consecutive-year average, or the consecutive no-hitters by Johnny Vander Meer. Today’s pitchers rarely toss three consecutive complete games, let alone three consecutive no-hitters needed to shatter this mark.

Lesser-known marks such as Joe Sewell’s 115 consecutive games without striking out or his mere four strikeouts in 155 games in 1929 should also weather the test of time.

ALIGNMENT OF THE STARS

Although this is a dangerous category to consider unbreakable, it is difficult to imagine anyone topping the outrageous one-day anomalies of some lesser-known players. Could any one collect four hits in an inning needed to break the record of three established by Boston’s Gene Stephens in 1953? Or score four runs in one inning to break Sammy White’s mark set in the same game? What about Fernando Tatis’s mark of two grand slams in one inning? Johnny Burnett’s nine hits in an extra inning game? In order to better Rennie Stennett’s record, someone would need to collect eight consecutive hits in a nine-inning game. These and others of their ilk appear safe.

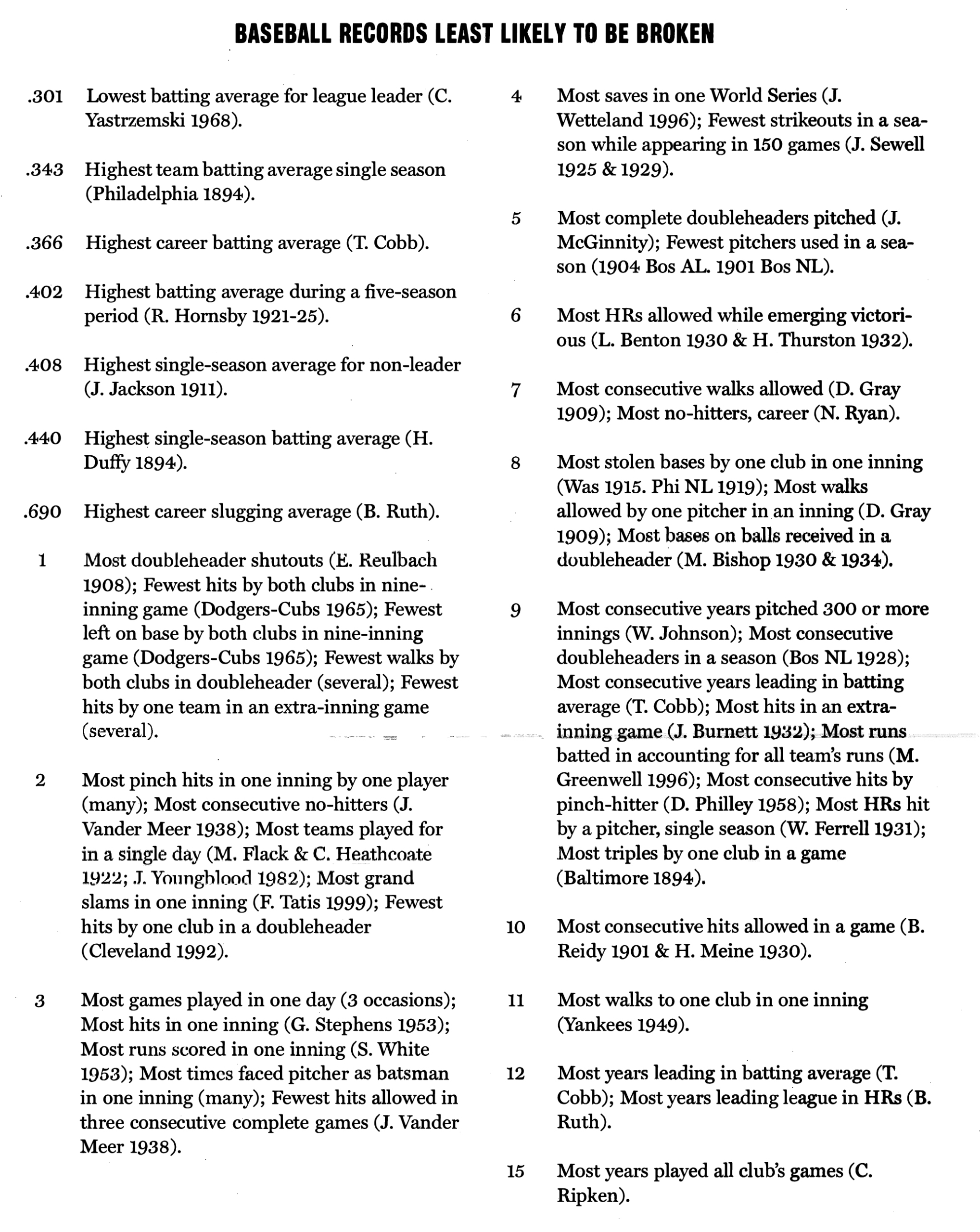

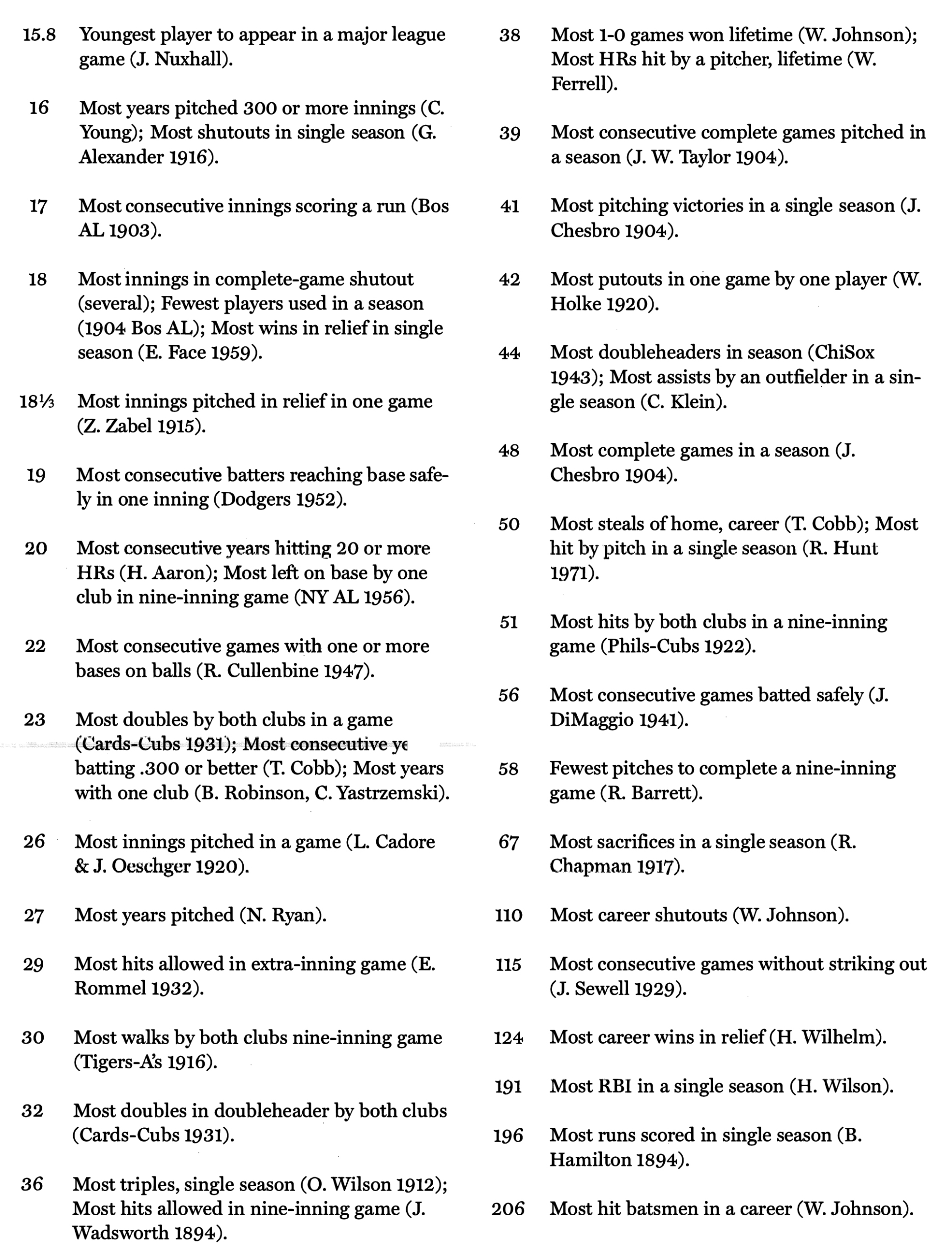

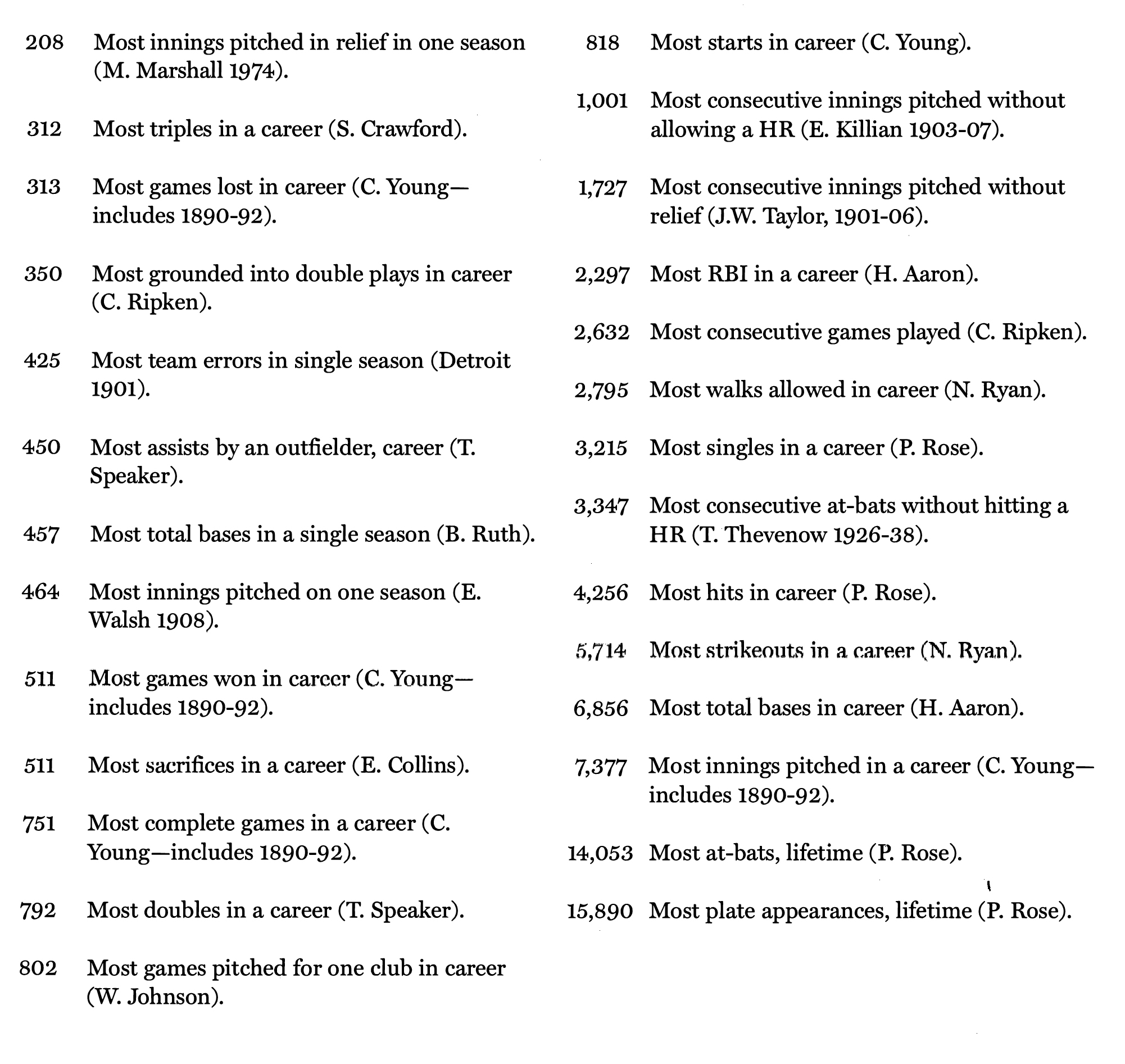

For those wishing to view a more comprehensive list of records considered “unbreakable” by members of the Records Committee, the following list is offered. It should be kept in mind, however, that a half-century ago, prognosticators confidently predicted the immutability of many marks no longer found on this list, such as Gehrig’s consecutive-games-played streak and Ruth’s single-season and lifetime home run benchmarks. Five years ago, who could have fathomed Barry Bonds’s spectacular assault on the record books? So will some of the following be displaced too?

Ironically, some may fall not because of a superior accomplishment on the field of play, but because of superior research by some of these same members of the Records Committee. Why, recently, the record for triples by a rookie was surpassed. Several committee members teamed, through excellent research, to increase the 1899 standard set by the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Jimmy Williams from 27 to 28. Which of the following will be the next to fall?