Beer Tanks and Barbed Wire: Bill Barnie and Baltimore

This article was written by Marty Payne

This article was published in Spring 2013 Baseball Research Journal

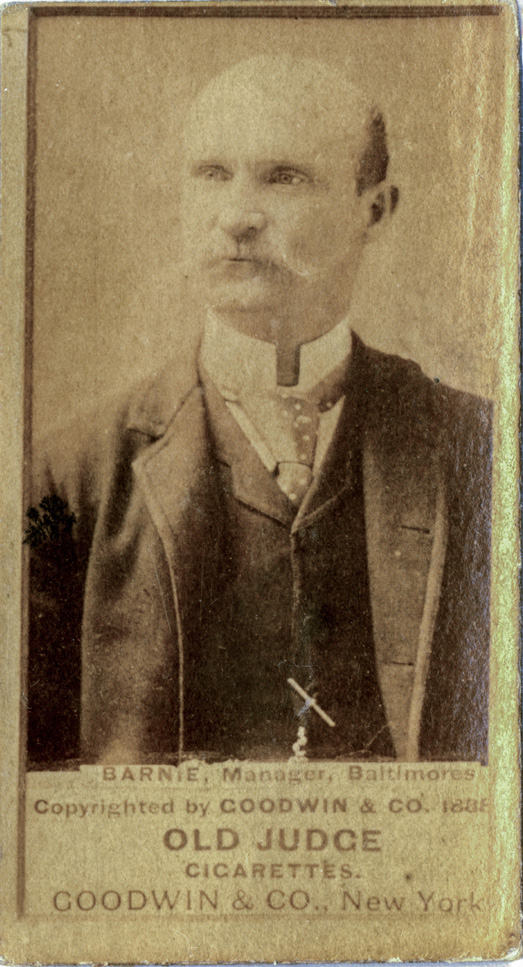

Billie Barnie had taken the reins of the Baltimore Club of the major league American Association in March of 1883. He was determined that the fans not suffer through another dismal season like the previous one. That aggregation, led by Henry Myers, had been hammered in local newspapers with headlines like “BAD GAME OF BALL—DISBAND OR GET BETTER,” “THEY CANNOT PLAY BALL,” “TRYING TO PLAY BASE BALL,” and “A COMEDY OF ERRORS.”1 To this end, Barnie went to New York City to sign Frank Larkin to play second base.

On his arrival Barnie found his projected infielder just released from custody for the attempted murder of his father. The new Baltimore manager insisted Larkin accompany him immediately back to Baltimore to avoid further trouble, but Larkin convinced Barnie to lend him $200 to settle some legal fees, and gave the promise to follow in a couple of days. Larkin couldn’t stay out of trouble that long. New York City police responded to a domestic disturbance call at an apartment. The police were at the door when a shot rang out. They then forced their entry as four slugs blew through the door, narrowly missing the officers. Once they were inside, Larkin pulled a razor from his pocket and slit his wrists. Leaning on a window sill was the wounded Mrs. Larkin, her clothes covered in blood from a wound and feigning death in fear for her life from her deranged husband.2

Barnie was out $200 and a second baseman in what would prove to be a perennial problem for the Orioles. In 1886 a scribe acidly pointed out, “What Baltimore needs is a complete system of sewage says the Herald. Most people thought what Baltimore needed was a second baseman.”3

Although probably not the worst in the American Association, Baltimore did have a reputation as a “tough town” to play in. The Sporting Life reported in 1885, “The Baltimore newspapers are largely responsible for the poor play of the local club. Constant abuse, fault finding and ridicule would demoralize any team.”4

opinionated newspaper retorted, “Baltimore getting reputation as a tough town to play in. Management alone cannot be faulted for its poor judgment. Players prefer to play elsewhere for less money than play in Baltimore. Everything is fine as long as he is perfect but one mistake and he is ridiculed and jeered, not only at the park, but on the thoroughfares.”5 Frank Bancroft, manager in Cleveland, publicly wondered why Baltimore had not won more games in 1883. “I don’t know what to say.” he responded to a reporter’s question, “Some have said it was the management: it is said they drink occasionally.” Bancroft went on to say he would gladly take Oriole pitchers Bob Emslie and Hardie Henderson, along with outfielder Jimmie Clinton.6

In their first season the new Baltimore front office of Alphonse T. Houck and Billie Barnie faced criticism for having a “cheap nine.” One reporter published the names of the players he thought needed to be released, including John Fox, Bill Gallagher, Dave Eggler, and Kick Kelly.7 Barnie was quick to defend his squad. “They say my nine is a cheap one; but is it? I am paying nearly as much money as St. Louis, and quite as much as the Athletics. I have not a cheap man with me.”8 Houck and Barnie failed to differentiate between expensive and good. Three years without improvement would elicit a bold declaration: “SOME MEN MUST GO.”9

Baseball fans were routinely greeted with headlines from the local papers including “PLAYING LIKE OLD WOMEN” and “THOSE POOR ORIOLES.” Later, “IT RAINED AND BARNIE’S BASE BALL CLUB ESCAPED DEFEAT.”10 One reporter carped, “The field management of the Baltimore Orioles is scarcely above the level of the Juvenile nines which play ball on the vacant lots of the city.” Later he noted, “Price of ham is 9 cents a pound. That would be a high price for some of the hams playing for Baltimore.” A day after the reporter had called for the release of several players in 1883, it was pointed out of the catcher, “With Kelly behind the bat the Baltimores can never win a game unless by a miracle… They might as well put a picket fence in to catch.”11

The national press blamed the local press for the city’s bad reputation as a baseball town. The local press pointed the finger at everybody but themselves, while Association opponents pointed to management and player habits. They almost forgot the umpires.

In 1884 the home crowd was rankled by the bad calls of umpire Brennan. At one point hundreds stormed the field, including a man with a “huge revolver” who threatened to shoot the arbiter if he made one more slipup. It took the police and both teams to clear the mob. After the game Brennan was slugged to the ground by a fan before being spirited to the Oriole club house, and then to Jimmie Clinton’s home, where he literally waited for the first train out of town. The individual who punched Brennan was later fined one dollar. There was no report of any charges being filed against the man with the “huge revolver.”12 When an umpire was subsequently threatened, he was said to be “Brennanized.” Barnie’s reaction to this incident was to install barbed wire around the stands along with signs prohibiting rowdy behavior and abusive language. The sign reduced neither. The barbed wire was still in place in 1887 when a large number of fans worked their way through or over the wire to mingle with the players before the game. The police escorted the unusually goodnatured crowd back to their seats without incident.13

But it was his players, not the fans, that Barnie had the most discipline problems with. In 1883 a headline ran, “PLAYERS UP ALL NIGHT—ONE IN STATION HOUSE.” There had been a masked ball at Kernan’s Theater in Baltimore which attracted a large crowd that lingered into the early morning. Pitcher Hardie Henderson got in a “wrangle” over a girl that ended in three players getting locked up. As a result Rooney Sweeney was fined $100, and Henderson $150 for drunkenness. Bob Emslie and Gid Gardner were each fined $10 for being up late. The fines had little effect.14

The Baltimore American set the contentious tone for the 1884 campaign before the season began by announcing, “It would be well to remember the position of last year’s Baltimore Club in the pennant race, which was largely due to the drunkenness of the men.”15 The Orioles wasted little time in showing nothing had changed. While the team was on a western road trip, Barnie let Gid Gardner sit in jail when arrested for beating a woman. Gardner caught up with the club in Toledo where he begged, and was granted, reinstatement. Barnie thought “the rest behind bars” had done him some good.16 When the team got to St. Louis, Gardner, Emslie, and Henderson joined up with Tip O’Neil and Fred Lewis of the Browns for a “jamboree” at a house kept by Maud Abbey. Late in the evening, O’Neil, for no stated reason, hurled a spittoon at the head of their hostess. Police were called in and Emslie and O’Neil were sober enough to make their escape through the yard. Gardner stayed behind to plead with the hostess not to press charges against his “pards,” but Henderson and Lewis were arrested, and behaved so badly on the trip to the station house that “extreme measures” had to be taken. Gardner went to Barnie for help but the manager let Henderson sit in jail. Barnie fined Emslie $100 and Henderson $150, plus $35 for bail.17 Pitchers Emslie and Henderson, the source of many of Barnie’s headaches during the 1884 season, would account for 59 of the team’s 63 wins that season.

The troubled Baltimore manager tried to improve the team’s fortunes with the signing of Matt Kilroy for the 1886 season. Despite Kilroy appearing in a leagueleading 68 games and compiling a 2934 pitching record, Barnie could not keep his team out of the cellar. Late in June it was asserted that one third of the club “consists of cast off beer tanks.”18] A few days later a 25–1 loss to Brooklyn was attributed to “fire water.” It was said the team had been “universally drunk” that day in what was described as a “bold display of contempt for management.” A.M. Henderson of the Baltimore front office defended the players saying that they were not drunk that day, nor any other day that Barnie had to come out of the stands to catch. Henderson went on to assert that the players were “gentlemanly and go to bed at 11:00 and rise at 9:00.” There weren’t many that believed him. A few days later it was observed that players seemed to “degenerate” once they got to Baltimore.19

If the players’ offfield behavior frustrated the fans, so did their execution on the field. Players certainly did seem to degenerate in Baltimore in every facet. The press often accused players of “playing for their release.” This meant that the player involved was playing under his ability in the hopes that the team would cut him, effectively making him a free agent. Often another Association, or a National League club was named to be in collusion with the perpetrator. Sometimes it was said to be done out of loyalty to a friend. When Gardner was sitting out a Barnie suspension, rumors spread that Emslie vowed not to win another game until his “pard” was reinstated.20

One of the greatest challenges Barnie faced during his nineyear tenure was a fourgame series with the St. Louis Browns in June 1887. The Browns were owned by Chris Van der Ahe and he dominated the Association from boardroom to ballfield. They were led by Charles Comiskey, Arlie Latham, and Tricky Curt Welch. Browns baseball included heavy doses of arguing, bullying, “kicking,” and fighting. On this particular road trip their antics had raised the ire in every city they visited, resulting in threats and assaults. By the time the team had reached Baltimore, the newspapers had dubbed their excursion the “Wild West Show.” Barnie made public announcements, posted bills, and implored Baltimore fans to be on their best behavior—and presumably stay behind the barbed wire. It didn’t work. In the ninth inning of an 8–8 tie, Curt Welch of the Browns intentionally bowled over Baltimore’s second baseman, Billie Greenwood. Many of the raucous crowd of nine thousand tumbled on to the field. One group from the bleachers was led by the mayor’s secretary and Colonel Wm. H. Love. Love made straight for Welch and demanded his arrest. From the mob people called out, “Kill him!” and “Hit him in the head!” Oyster Burns, captain of the Orioles, hobbled out on his crutches to confront Browns captain Charlie Comiskey, and the scuffle nearly turned into a brawl before the already burdened police intervened. But the contingent of officers could not get the fans back into the stands, so the game was called back to the eighth inning and declared a tie. Welch was ushered to the safety of the visiting clubhouse as a large crowd menacingly lingered outside. Dave Foutz— St. Louis pitcher, Maryland native, and fan favorite— went out and spoke to soothe the unruly throng. This served as enough of a diversion to get Welch out a side door and into a carriage for the nearest magistrate at Waverly Station. But the ruse was spotted and a pack of boys and young men chased the carriage on foot. Waiting at Waverly Station was another mob of inflamed fans who had anticipated the culprit’s eventual destination. The Baltimore club posted the security for Welch to appear for a hearing the next day.

Welch thought he was out of the woods when he finally arrived at his lodgings at the Eutaw House that evening. He and a couple of teammates walked into a nearby cigar stor, and on their emergence found yet another menacing crowd milling about and closing in despite there being six uniformed police officers on hand. According to the report Welch tried to act nonchalant, but failed to light his cigar in a dozen attempts. Welch and his teammates left quickly around the corner with their escort, and no further incidents were reported. At the hearing the next day, Col. Love and the mayor’s secretary were among the group vehemently pressing charges, but Greenwood testified that Welch had done nothing out of the ordinary, while team owners Van der Ahe of the Browns and Van der Horst of the Orioles wondered why the law was interfering with the events of a simple game of baseball. Welch was wisely held out of that day’s game.21

Things didn’t seem to get better for Barnie and the Orioles. In June 1888 Barnie complained that local reporters were trying to “drown them.” Mike Griffin was one of the best center fielders in either league, and Blondie Purcell was a solid player, but the performances of both were described as “rotten.” A day later it was declared by the press that the players were “bleeding the bank dry with their indifferent play.”22 Management’s frustration seemed to spill over when a seven-year-old boy grabbed a ball hit into the stands and took off with it. The apparently well conditioned Secretary Hiss of the Baltimore front office chased the young lad ten full city blocks before he caught up and wrestled the ball from the exhausted miscreant. Not content with the mere recovery of team property, Hiss immediately dragged the thief before the nearest justice of the peace. Justice Hicks, exercising some modicum of reason, released the boy. It is presumed that Hiss then walked the ten blocks back to Oriole Park with his prized ball.23

Maybe things were improving for Barnie by 1889. There were no reports of jamborees, sprees, lives being in danger, or huge revolvers. While in Columbus, Ohio on a western road trip, Matt Kilroy and his teammates found a novel way to while away the hours between games. They would dangle a rod and line with food on the end from their hotel window to the alley below. When a rat took the bait, it was “jerked heavenward.” Kilroy was not only the ace of the pitching staff, but the ratcatching rotation as well. He landed nineteen in a single afternoon. There was no mention of what they did with their catch.24

EPILOGUE

These incidents are but a few of the many that Billie Barnie had to contend with from his players, fans, press, and opponents during his nineyear tenure in Baltimore. He was 30 years old when he took the helm of the Baltimore Orioles and was mostly portrayed in the papers as the managing partner of the club. It was always Barnie that was mentioned as representing Baltimore at Association meetings, and at an early date he served on both the Scheduling and the Rules Committees. Later he would serve on the joint rules committee between the National League and the Association where he made his presence felt.25

By 1886 most teams employed “coachers” who would stray from their positions near first and third bases to home plate where they would yell, swear, and motion to catchers and umpires in order to distract them. Another tactic they employed was for the coacher on third to break down the line with the runner, and when the runner stopped, continue down the line in an attempt to decoy a wild throw, or simply rattle the pitcher. Barnie was so annoyed with these ploys that he telegraphed the Association with the suggestion that the coachers be confined to a box 15 feet by 35 feet, set up 75 feet from home plate. The Association rules committee immediately implemented the coaches box in the middle of the 1886 season.26

He also became frustrated with his team’s unstructured pregame warm up. Whether an innovation, or copied from another, Barnie insisted on organized batting practice. At first he simply stipulated that each player have his turn, but within a month he specified the number of pitches each was to hit.27

Despite never finishing higher than third place, Barnie also had a reputation as a keen eye for talent. While he was saddled with unsuccessful signings like “Whipoorwill” Goetz, “Frogeyed” Mike Muldoon, and Kick Kelly, he did bring many talented players into the Association’s fold. They included Oyster Burns, Matt Kilroy, Mike Griffin, Tommy Tucker, and Bill Shindle. Later he would leave Sadie McMahon, Wilbert Robinson, and John McGraw for Ned Hanlon’s National League Champion Orioles.

In 1890 Baltimore attempted to enter the National League and was eventually blocked out of both major leagues. They ended up in the minor Atlantic Association, but when American Association teams began to fail at the box office in competition with the Players and National Leagues, the Orioles were called back to complete the schedule. Barnie was also tasked at that time with running the struggling Athletic franchise, and preserving their star players for the Association. For his contributions, Barnie was named vice president of the Association for the 1891 season.28 Barnie terminated his association with the Orioles when he announced his resignation effective the end of the season. Baltimore would then be included in the consolidation into the National League with Ned Hanlon at the helm.

MARTY PAYNE has been a member of SABR since the early 1990s and lives in St. Michaels, Maryland.

NOTES

1. Headlines are from the Baltimore American, June 8 1882, June 11, 1882, July 22, 1882, and July 26, 1882.

2. “Larkin On A Spree; Second Baseman in Trouble,” Baltimore American, April 26, 1883.

3. Baltimore Daily News, April 13, 1886.

4. The quote from Sporting Life was reprinted in the Baltimore Daily News, July 6, 1885.

5. Baltimore Daily News, July 17, 1885.

6. Baltimore American, October 8, 1883.

7. On Houck see Baltimore American June 23, 1883; The call for release of players is from the Baltimore American, June 25, 1883.

8. Baltimore American, July 1, 1883 as cited from the Pittsburgh Dispatch.

9. Baltimore Daily News, July 19, 1886.

10. Baltimore American, June 25, 1885 and August 30, 1885. Baltimore Daily News, August 21, 1888.

11. On the comparison to Juvenile nines see Baltimore Daily News, June 4, 1886. The comparison to ham is from the Baltimore Daily News, July 6, 1886. The criticism of Kelly is from the Baltimore American, June 26, 1883.

12. Reports are from “Bad Row at Oriole Park,” Baltimore American, June 13, 1884, and Baltimore Day, June 13, 1884. For more detailed account see, Marty Payne, “The Undesirable Position,” Base Ball, A Journal of the Early Game, Fall (2007): 104 –114.

13. For the installation of barbed wire see the Baltimore Day, June 16, 1884, and for its continued use the Baltimore American, May 3, 1887.

14. Baltimore American, September 5, 1883.

15. Baltimore American, March 19, 1884.

16. Gardner’s travails are reported in the Baltimore Day, June 20, 1884, June 25, 1884, and June 28, 1884.

17. See the Baltimore American, July 4, 1884, and July 5, 1884.

18. Baltimore Daily News, June 21, 1886.

19. For accusations of team’s condition during loss see Baltimore Daily News, June 25, 1886 and June 26, 1886. Henderson’s defense is in the Baltimore Daily News, June 28, 1886.

20. Baltimore American, July 4 and July 5, 1884.

21. See “Welch in Danger,” Baltimore American, June 17, 1887 and, “Welch is Fined $1,” Baltimore American, June 18, 1887.

22. The accusation is in the Baltimore American, June 17,1888. Comments on the play are from the Baltimore American, July 28, 1888 and July 29, 1888.

23. Baltimore American, July 31, 1888.

24. Baltimore American, July 28, 1889.

25. See Baltimore American, October 1, 1882, and the Baltimore Day, March 13, 1883. Van der Horst’s does not appear in either newspaper until the mid 1880’s. Barnie was always the front man and representative in the media. See Baltimore American, November 10, 1889.

26. For a description of the yelling tactics see the Baltimore American, September 12, 1885. For the base running ploy see Baltimore Daily News, April 15, 1886. Barnie’s proposal for the coach’s box is in the Baltimore Daily News, June 10, 1886.

27. Baltimore Daily News, April 30, 1888 and May 22, 1888.

28. Baltimore American, December 7, 1890.