Bibb Falk: The Only Jockey in the Majors

This article was written by Matthew Clifford

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

In the old days of professional baseball, players fist-fighting on and off the field was not uncommon. Players would scream at each other. Some would tease. Many others were just downright mean.

One player in particular earned a nickname that perfectly described his slick dugout demeanor. The handle followed him throughout his days in the major leagues and all the way to baseball cards printed after his death.

In 1978, when asked who coined his nickname, “Jockey,” Bibb Falk replied with a sharp southern drawl, “I don’t know where the hell it came from.”1 Today, many baseball historians incorrectly dub Falk as an overaggressive player who screamed at and “rode” his opponents, as a jockey would ride a horse.

His manipulative skills were strongest during batting practice before games or when opposing players walked past Falk’s dugout perch. He had mastered a personal technique to take the mental edge off his rivals by questioning them about false rumors that had been started by other players. The tactic forced his competitors to focus their attention on Falk and his position as an innocent “middle-man” that stood between them and another player who shared a rumor with Falk. It is up to the reader to decide which method of “jockeying” is cruder.

Falk explained his moniker in a 1978 interview: “I wasn’t hollering at nobody during no game. I was just “jockeying” between somebody. It was more kidding than riding. Sometimes we’d be batting at home and the visiting team would have to come by our batting cage to get to the other side of the bench and you’d hear one of the players say, when so-and-so comes by, ask him about this, see? Something happened to him, see? And then he’d come by and get tough and say, what’s this I heard about that and they say, where in the hell you get this?”2 It is worth noting that Falk was giggling during this portion of the interview.

Bibb Augustus Falk was born in Austin, Texas on January 27, 1899. His first name led to teasing that included the phrase “bib and tuck’er,” an old-time slang expression describing someone who was dressed nicely. In fact, he was often referred to during his playing career as “Bib.” (His middle name, long believed to be simply “August,” is apparently the longer appellation, according to many contemporary documents including those at the Texas State Historical Association.)

Falk learned the game of baseball living close from Riverside Park, the home field of the Austin Senators of the Texas League. Bibb visited the field frequently and eventually earned employment at the park as the Senator’s batboy while working between innings selling bags of peanuts to fans in the bleachers.

He honed his baseball talents at the Stephen F. Austin High School. William “Billy” Disch, head baseball coach from the University of Texas, reviewed Bibb’s abilities during one of his high school performances. The coach quickly approached the high school senior and invited him to attend UT.

Falk accepted Disch’s offer, but before he could enroll at UT he had to join up with Uncle Sam. In April 1917, the United States joined the war against Germany and Bibb enlisted with the U.S. Naval Reserves.

After the war ended in 1918, Bibb returned to Austin and followed the tutelage of Coach Disch, who taught young Falk his baseball.

During his sophomore, junior, and senior years at UT, the left-handed Falk played varsity and, as a pitcher, was undefeated in all three seasons. In spring 1919, the Chicago White Sox came to Austin for spring training and played against Disch’s UT Longhorns. Falk’s flair caught the attention of White Sox management during the exhibitions. Disch communicated with the White Sox via letters during summer 1919, and Falk eventually signed his first professional baseball contract with Chicago. Falk explained the details of the transaction: “Well, it was all settled by wire and mail between the White Sox and Disch and myself. They just sent a contract down here after school that summer. I signed in the summer before I reported. In those days you could do that in college, you know. So I actually signed the contract in the summer of ‘19 and reported in June of ‘20.”3

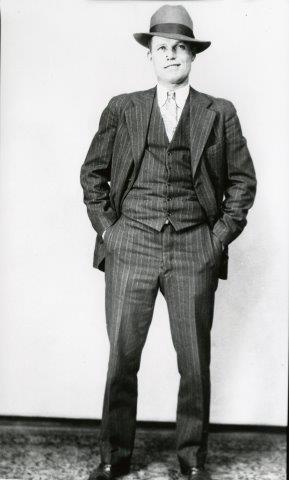

A nattily attired Bibb Falk.

The 1919 World Series “Black Sox Scandal” opened the door to Falk’s career in the major leagues. “I thought I’d be farmed out because they had a great team back then. They had been great until they threw the series away. They had a pretty good outfield and that was my break it was when they’d been kicked out. They had to rebuild, see. That was my break. If it hadn’t been for that, I’d been sent down.”4

Falk initially joined the Sox in July 1920 but did not play regularly until the last few games of the season, by which the team’s involvement in the scandal around the 1919 World Series became known. (Commissioner Landis eventually banished eight players from the White Sox roster after a Chicago court acquitted them of fraud. Landis knew that the players had “thrown” the World Series with weak performances for the benefit of gamblers.)

The Black Sox trial ended in July 1921, by which time “the southpaw from the South” had already been summoned to the south side of Chicago. Falk stepped over the minors and headed directly to the majors.

“ I joined them (the White Sox) in Philadelphia on the road and I finished the road trip with them. Stayed with them. I never did play much,”5 Bibb recalled. “I did pinch hit there once or twice after a game they’d lost. Something like that. Till the last week of the [1920] season when those [eight] fellas got kicked out [by Landis], then I played every day.”6 Bibb’s first major league appearance wearing a White Sox uniform was July 17, 1920, when he was called to pinch-hit against the New York Yankees at the Polo Grounds.

The outfield garden of Chicago’s Comiskey Park had been previously occupied for five years (1915–1920) by the legendary “Shoeless” Joe Jackson. Bibb would carry his nickname “jockey” while toting the title, “The Man That Replaced Shoeless Joe” for the rest of his life. Falk explained his feelings of Chicago’s notorious “eight men” since he shared their dugout space moments before they were dismissed.

“ I got a kick out of Buck Weaver. He used to work at the windows at the race tracks in Chicago for a while and we’d have a rainy day, we’d go out to the tracks, see. I’d see him at the window and I’d talk to him. Anything that Weaver said, Jackson would do. He (Jackson) was too dumb to be a leader, see? Jackson was a great hitter. He hit .370 in the World Series and he was trying to throw it. He was a nice quiet fellow.”7

In 1921, Falk, just 22, began to make headlines for the White Sox. He excelled in some areas, collecting 31 doubles and 82 RBIs. Falk’s progress was impressive despite ranking fourth in the American League with 69 strikeouts.

Bibb’s bat continued to produce in 1922. His bat also got him into some trouble on June 7, however, after he threw his stick while arguing with umpire Frank Wilson’s decisions of pitched balls and strikes. When the lumber went sailing, Wilson christened Bibb with his first big league ejection. Falk ended the season hitting .298 with 27 doubles, 12 homers, and 79 RBIs.

As the World Series between the Yankees and Giants was being played, Bibb Falk and a handful of other big-league players were selected to participate in an off-season barnstorming schedule in Japan. AL President Ban Johnson and Commissioner Judge Kenesaw Landis authorized the tour, which was supervised by AL umpire George Moriarty and organized by former major leaguer and Japanese baseball coach Herbert Hunter.

Falk recalled the details of his excursion: “I got to travel a lot and it never cost me any money. There was that barnstorming trip promoted by Herbie Hunter…we had Waite Hoyt, Herb Pennock, Freddie Hoffman, Joe Bush, George Kelly, Casey Stengel, Irish Meusel. All them just had been in the World Series. Amos Strunk and myself from the White Sox, a couple Cleveland guys, Luke Sewell and Riggs Stevenson, Bert Griffith from Brooklyn, Doc Lavan from the Cardinals and their wives. We had twenty-six in the party and we sailed out of Vancouver October the 19th and got back in Frisco February the 1st 1923. We did it all by boat, see? It took eleven days by boat to get there.”8

After arriving in Japan, Hunter’s “All-American” team played against Japanese college teams, industrial teams and amateur teams. Falk and his teammates stopped in Seoul, Korea to play a bit more before parking in Peking, China to spend a day sightseeing.

The next stop was Shanghai and a week-long visit to the Philippines where the All-Stars played an Asian military team. While Falk was enjoying the Orient, baseball rumors around the stovepipe mentioned the possibility of a trade to the Yankees, who wanted a replacement for floundering outfielder Lawton “Whitey” Witt. The papers kept the gossip flames hot until March 1923, but Chicago fanatics were relieved that Falk would continue working for the White Sox. In late April, a sports rag predicted a bright future for the Comiskey asset: “Falk is a dangerous batsman and has the ability to become a star if he makes the most of his possibilities.” 9

Boss Charles Comiskey and his secretary Harry Grabiner tightened their grip on Falk and opened their checkbook a bit wider for the Texan, increasing his yearly salary from $3,600 to $4,800 for 1923. Unfortunately, Falk was not fully healthy. He missed action from August 25 through the end of September due to trench mouth (i.e. gingivitis—swelling of the gums). White Sox manager Kid Gleason also sat Falk on occasion. So Bibb’s usual impressive RBI total dropped by half and his doubles by a third. His monumental moment in 1923 came on June 8 as the White Sox challenged the New York Yankees at their home field. That day, Falk hit the longest single of his career. The hit travelled 420 feet and has been mooted as the seventh longest single in major league history.10

Following the ‘23 season, the 56-year-old Gleason retired. Comiskey quickly appointed Frank Chance, a former Cubs great who heretofore had managed the Boston Red Sox, to change the color of his hose and run his Chicago club. Chance accepted Comiskey’s offer and hired longtime Chicago Cubs companion Johnny Evers as a coach. When spring training began, Frank was not there due to illness. Rumors of Chance battling sinus infections, gall stones, and bronchitis covered the newspapers in spring ‘24.

Unable to attend to his new team, Frank Chance was replaced first by Johnny Evers then by Eddie Collins. Chance resigned and died on September 15 of an undisclosed illness. Days after his passing, the papers mentioned Chance’s prediction for Bibb Falk: “Keep that young fellow in the game regularly and it will not be long before you will find him batting rings around all the rest of them.”11

Chance’s forecast had been confirmed by the end of the 1924 season. Bibb collected 185 hits, including 37 doubles, and 99 RBIs. The Texan’s .352 mark ranked third in the American League. Falk fell short only to Cleveland’s Charlie Jamieson (.359) and the Yankees’ Babe Ruth (.378). The White Sox sank into last place that season, however, regardless of Bibb’s impressive performance.

In February 1925, Bibb’s younger brother, Chester “Chet” Falk, signed on to pitch for the St. Louis Browns. Following in his big brother’s footsteps, Chet worked under the management of “Uncle Billy” Disch at the University of Texas before the Missouri scouts came calling.

Bibb’s lumber made big crashes during the 1925 season under new manager Eddie Collins. Comiskey raised Falk’s $4,800 salary to $7,500 since the outfielder’s bat brought extra spins to the White Sox turnstiles. So, with a heavy bat and heavier pockets, Falk appeared in more games than any other player on the roster. As he had in 1924, he drove in 99 runs.

One of his Chicago teammates, Ted Lyons, remembered Falk’s power in a 1977 interview: “Falk hit line drives and usually right through the middle of the diamond. One year he hit five pitchers with line drives. He hit one between the eyes, one under the heart, one in the stomach, one on the shin and one on the chin, breaking the chap’s jaw.”12

Lyons was recalling an incident that occurred at Comiskey Park on May 29, 1925, when the White Sox welcomed a visit from Ty Cobb and his ferocious Detroit Tigers. Falk stepped to the plate to face Detroit right-hander Sylvester “Syl” Johnson. Bibb slammed a pitch directly at Syl’s head, smashing several bones in the pitcher’s face and causing a broken jaw that required a lengthy stay at Chicago’s Mercy Hospital. The Falk-induced injury branded Johnson a jinx, forcing the pitcher off the Detroit bench and eventually off American League scorecards. But exactly one decade later, on May 29, 1935, Syl, now pitching for the Philadelphia Phillies, became the last pitcher to strike out the illustrious Sultan of Swat, George Herman “Babe” Ruth, in a major league game.

Bibb put in a hard season’s work in 1926 as he appeared in every White Sox game on the schedule. Eddie Collins remained at the helm and witnessed Bibb’s thunderous swings that produced 108 RBIs, 43 doubles, and a .345 batting average, seventh best in the AL. He also led the league in fielding average among outfielders at .992. Falk’s performance led the AL to place him 12th place in the League Award voting.

At the end of the season, he recapped his feats to Grabiner and requested a bonus. The secretary advised Falk to compose a letter to Comiskey with details of his request. A few days later, Falk opened a letter that held only disappointment. The irritated Texan clearly remembered the details decades later as he explained the Comiskey letter during a 1978 interview. “I got a letter back signed Comiskey but that Grabiner—he could imitate Commy’s signature and I’m pretty sure as far as this statement I’m going to give you, I figure he signed it. It said, “In all my years in baseball I never heard of a player refunding any of his money when he had a bad year so why should I give you extra money for having a good year?”13

Comiskey’s notoriously tight purse strings affected Falk and caused a rift that worsened in 1927. That year, the White Sox organization replaced Eddie Collins with the club’s reliable catcher, Ray Schalk. Falk, dissatisfied with his pay rate despite a 33% raise, turned in numbers poorer than some of his earlier performances.

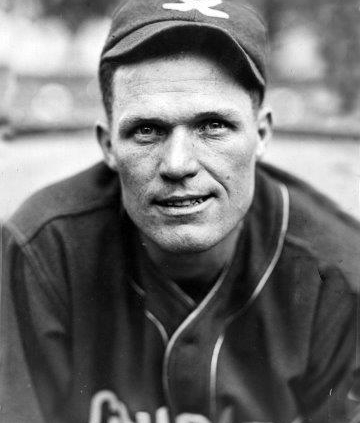

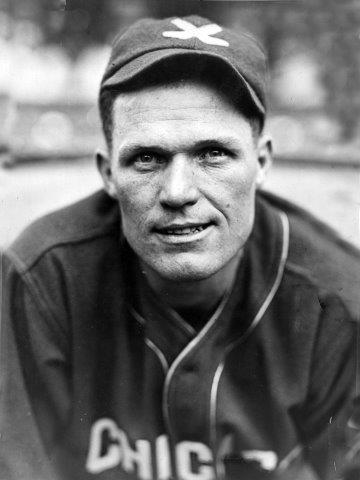

Falk shown in 1926.

In 1928, skipper Schalk was replaced by Russell (aka “Lena,” or “Slats”) Blackburne. Falk started the season with vigor until another case of gingivitis forced him out in late June. Altogether he batted .290 in 98 games with only 18 doubles and 37 RBIs.

Following the campaign, Comiskey attempted to cut $2,500 from Falk’s yearly income before dealing him to the Cleveland Indians in exchange for backstop Martin “Chick” Autry.

“They (Chicago) wired me and told me I’d been traded to Cleveland,” Falk explained. “Grabiner sent it…signed Comiskey. Cleveland sent me a contract without the cut so I saved $2,500 there.”14

When he arrived to play in Ohio, Falk was pleased to work with his old White Sox teammate and friend, Roger Peckinpaugh, the manager of the Indians. “Peck” put Falk to work at Cleveland’s League Park for the next three years. Falk collected 157 RBIs for the Indians from 1929–1931, but in the last two years was only a part-time player.

Peck, perhaps through Indians GM Billy Evans, extended an invitation for Falk to become a manager for Toledo in 1932. The Mud Hens, Cleveland’s top minor league club, needed a pilot.

Falk accepted the offer to become a playing manager for the Mud Hens, but his time with the club was bleak; the Great Depression heavily affected the Toledo turnstiles. “I played the outfield and managed there in Toledo and they gave it up because they’re in depression. See, we finished third [sic: actually fourth] and lost a lot of money over there. We wasn’t drawing. Toledo was broke. All the banks were closed.”

In 1933, Peck called Falk back to Cleveland to work as a coach. Peckinpaugh, however, was let go in June after the Indians slipped from first place to fifth. Cleveland owner Alva Bradley appointed Walter “The Big Train” Johnson to replace Peck. Bibb, as interim manager, learned that Johnson was bringing his own coach to Cleveland.

Later that summer, Bibb contacted his Chicago comrade, Eddie Collins. Eddie had been hired as Vice President of the Boston Red Sox and had a position ready for Falk. Collins had him scout for the rest of the season then assume the role of a major league coach for 1934.

After one season coaching in Boston, Falk returned to his hometown of Austin, Texas. He worked five years (1935–1940) as a scout for the Red Sox while enjoying the off-season at his home address.

Falk bid a permanent farewell to the majors in 1940 after his long-time friend and mentor, Billy Disch, became ill in 1939 and requested Bibb’s assistance. Disch had never left his post as UT’s head baseball coach. In 1940, Falk and Disch worked together at Texas. Disch worked as an assistant to Bibb, who assumed the role of head baseball coach.

After successfully piloting the Longhorns baseball team for three years, Falk stepped away from the field and rendered his services to the U.S. Air Force during World War II. Bibb earned the rank of sergeant shortly after his enlistment at the Randolph Air Force Base in Texas. In 1944, Falk worked on the base as coach for the Randolph Ramblers baseball team. The Ramblers were one of the many teams recognized in the Military Service League.

Two of Bibb’s players, pitcher Dave “Boo” Ferriss and catcher Tex Aulds, eventually became property of the Red Sox, Ferriss before his recruitment with the U.S. Air Force and Aulds later.

After serving Uncle Sam from 1943 to 1945, Falk returned to UT’s Clark Field to coach the Longhorns. Those who played for Coach Falk say unanimously that he was a big leaguer all the way. He often admonished his men, “You might not be big leaguers, but you can sure act like you are.” A world-class cusser, his most contemptuous epithet was “bush league,” and he would not tolerate anyone wearing a Texas uniform acting like a “busher.” He treated his players like professionals and he expected them to act like they were big leaguers on the field.”15

Falk’s players described him with adjectives like “a crusty wildcat with a fiery tongue” or as “an ornery, intimidating man.” One player explained that his Texan coach could curse consecutively for one hour without ever repeating himself. Bibb’s tough and gritty exterior transformed undisciplined college athletes into baseball machines as each of his pupils discovered their strongest abilities on the field. During his 27 years at the helm of the Texas Longhorns, Falk and his men won 470 games, 20 victories in the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) Southwestern Conference, and two College World Series Championships (1949 and 1950).

In 1953, Bibb and his Longhorns bid a final farewell to their coach and mentor, “Uncle” Billy Disch, who passed away, leaving a legacy of baseball memories and dedication to Austin’s UT.

In 1962, Bibb was elected to the Longhorn Men’s Hall of Honor and the Helms Athletic Foundation College Hall of Fame in 1966.

Awards continued to follow Falk after he left UT. In 1968 the ABCA (American Baseball Coaches Association) added him to their Hall of Fame. Twenty years later Bibb was inducted to the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame. In early 1975, the University of Texas completed construction of the $2.5 million Disch-Falk Field, honoring the two men who served Longhorns baseball for a combined 54 years.

Falk, who never married, spent his retirement years living in Austin with his younger sister, Elsie, until her death in 1980. Still tough as nails, Bibb remained healthy until 1988 when he began having heart difficulties. On June 8, 1989, Bibb Augustus Falk passed away at Brackenridge Hospital in Austin at age 90. He was the last surviving member of the 1920 Chicago White Sox.

Years after his death, Falk was elected to the 2007 College Baseball Hall of Fame.

In 2001, historian and author Bill James wrote an interesting synopsis of Falk: “He was an unusual man. A lifelong bachelor, he was devoted to baseball and devoted to his players. He was stubborn, yet good-natured. He would leave perfectly good bats and balls in the trash so that neighborhood kids could have good equipment to play with, but he wouldn’t be caught giving them anything. Retiring at 65 [sic: 68], he lived in Austin another 24 [sic: 22] years before he died, and during that time he hardly ever missed a Texas home baseball game.”16

Today, White Sox fans can view a slice of history on a wall near the concession stand corridors at U.S. Cellular Field in Chicago. A life-size black and white photograph of Bibb Falk and his heavy bat occupy a section of the wall, along with a listing of his achievements working for Charles Comiskey.

MATTHEW M. CLIFFORD, a freelance writer from suburban Chicago, joined SABR in 2011 to help preserve accurate facts of baseball history. Clifford’s background in law enforcement and knowledge of forensic investigative techniques aid him in historical research and data collection. He has contributed to the SABR Biography Project and the 2013 “National Pastime.”

SOURCES

Newspapers and wire services:

The Sporting News (1920–1989)

The Associated Press (1920–1989)

The United Press (1920–1989)

Additional assistance:

Jason Culver (Research assistance)

Graves-Hume Public Library, Mendota, Illinois

Somonauk Public Library, Somonauk, Illinois

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

The National Baseball Hall of Fame Museum

NOTES

1 Dr. Eugene Converse Murdock Audio Interviews. Recorded 1978 in Austin, TX. Mears-Murdock Exhibit. Cleveland Public Library, Cleveland, OH.

2 Dr. Eugene Converse Murdock Audio Interviews. Recorded 1978 in Austin, TX. Mears-Murdock Exhibit. Cleveland Public Library, Cleveland, OH.

3 Dr. Eugene Converse Murdock Audio Interviews. Recorded 1978 in Austin, TX. Mears-Murdock Exhibit. Cleveland Public Library, Cleveland, OH.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Dr. Eugene Converse Murdock Audio Interviews. Recorded 1978 in Austin, TX. Mears-Murdock Exhibit. Cleveland Public Library, Cleveland, OH.

8 Ibid.

9 “Infield Rates High,” The Syracuse NY Journal, April 6, 1930, p. 30.

10 Bill Jenkinson, Baseball’s Ultimate Power: Ranking the All-Time Greatest Distance Home Run (Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2010), p. 285.

11 “Bibb Falk Fulfills Prediction Made By Frank Chance,” The Daily Sentinel of Rome NY, September 20, 1924, p. 8.

12 Dr. Eugene Converse Murdock, Baseball Players and Their Times: Oral Histories of the Game, 1920-1940 (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Publishing, 1991), p. 235