Boxing At The Big Ballpark In The Bronx

This article was written by John J. Burbridge Jr.

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

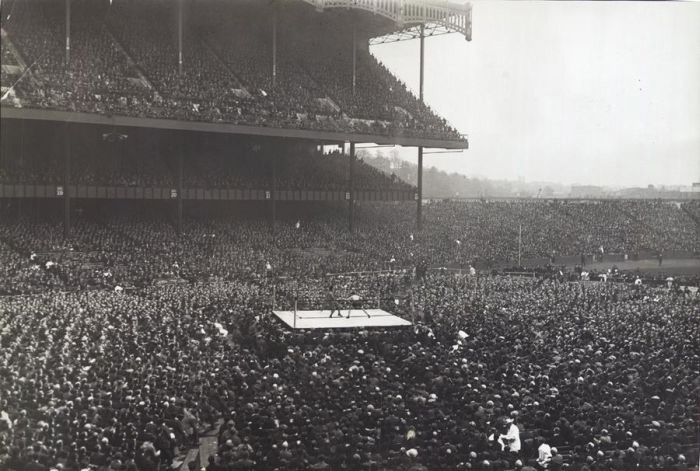

Yankee Stadium hosted its first boxing match on May 12, 1923. (Public domain)

Certain sporting events have the ability to gain the attention of an entire nation. The World Series, Super Bowl, and World Cup are such examples. Some heavyweight boxing matches can also create such interest. Two such fights in the 1930s between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling at Yankee Stadium became instant classics as they had the attention of most of the world, especially Louis’s America and Schmeling’s Germany. The following article will explore the role Yankee Stadium played in boxing history with particular emphasis on the two Louis-Schmeling fights.

In the early twentieth century, baseball was America’s sport. Its popularity was enhanced by the emergence of Babe Ruth, the Sultan of Swat. His ability to hit home runs, 59 in 1921 and 60 in 1927, changed the game and made The Babe a national hero. This 1920s also saw the advent of radio. Listening to baseball games created new fans throughout America.

Another sport that grew in popularity in the 1920s was boxing. Once again, the surge in interest was fueled by a charismatic figure, Jack Dempsey, the Manassa Mauler. Dempsey became heavyweight champion in 1919 with his vicious knockout of Jess Willard in Toledo, Ohio. With Dempsey’s arrival on the scene, boxing promoters began looking for large venues to stage fights.

To illustrate, boxing promoter Tex Rickard realized his upcoming match between Dempsey and Georges Carpentier, a handsome and popular Frenchman, would attract a huge crowd. Since it proved difficult to stage the fight in New York City, Rickard decided to build a stadium in Jersey City at Boyle’s Thirty Acres.1 This wooden stadium, built in several months, could accommodate over 90,000 fans. Before a packed house on July 2, 1921, Dempsey knocked out Carpentier in the fourth round. This was the first boxing match that generated gate receipts of over $1 million.2 It clearly demonstrated the need for large stadiums to house boxing matches.

In 1920 the New York Giants informed the ownership of the New York Yankees that they would not renew the lease allowing the Yankees to play at the Polo Grounds, home of the Giants, after the 1920 season.3 The Yankees had been playing at the Polo Grounds since 1913. With Sunday baseball now allowed in New York City, the Giants no longer wanted to share lucrative weekend dates with the upstart Yankees.4 The Giants did soften their eviction stance but raised the rent by a significant amount.5 Given such actions by the Giants, the Yankees owners decided they needed their own ballpark. They acquired property across the Harlem River in the Bronx and built Yankee Stadium. It opened for the 1923 baseball season.

On May 12 of that year, The Stadium held its first boxing matches. Headlining the fight card were separate matches featuring former heavyweight champion Jess Willard and heavyweight contender Luis Angel Firpo. Willard won on a technical knockout while Firpo won via knockout before 63,000 fans.6 This large crowd for nontitle fights clearly illustrated that Yankee Stadium could house major boxing matches.

Dempsey went on to lose his heavyweight title by decision to Gene Tunney in 1926. While Dempsey considered retiring, he returned to the ring in 1927 for his only appearance at Yankee Stadium. He knocked out Bob Sharkey in the seventh round before 80,000 fans. Dempsey went on to fight Tunney once again in 1928, losing by decision.

In 1936 and 1938, the two most memorable fights at Yankee Stadium were held. They featured Max Schmeling from Germany and Joe Louis. Schmeling had been the heavyweight champion when his foe, Jack Sharkey, was disqualified for a low blow in the seventh round in a 1930 fight. Sharkey later regained the title by beating Schmeling via a split decision. Joe Louis had won his first 24 fights, most by knockout. By fighting and defeating Schmeling, he would be in line for a title fight against James J. Braddock, the recently crowned heavyweight champion. Schmeling was also hopeful of a title fight if he defeated Louis. The first fight between the two was scheduled for June 19, 1936.

The rise of Adolf Hitler and Nazism in Germany contributed significantly to the atmosphere surrounding these two fights, especially the second. The so-called Nuremberg Laws supposedly purifying the Aryan race had been passed in 1935.7 Schmeling was considered a representative of that society and the Aryan race although not a member of the Nazi Party. Louis, being an African American, was viewed as inferior in Nazi Germany and by some people in the United States.

It was fairly obvious Louis did not consider Schmeling a serious challenger prior to the first fight. Training in Lakewood, New Jersey, he was seen often on the golf course instead of sparring. He also appeared to be very active sexually.8 Louis may have been influenced by the fact that Max Baer had knocked out Schmeling, and Louis did the same to Baer.

While Louis may have considered Schmeling lightly, Schmeling prepared very seriously for the match. In December 1935 he attended the fight between Louis and Paulino Uzcudun. After that fight, Schmeling proclaimed that he “saw something.”9 Had Schmeling unearthed a flaw in Louis’s approach? While a 10-to-1 underdog, Schmeling felt he would win the fight.

That flaw became apparent before a sellout crowd at Yankee Stadium. For the first three rounds, Louis punished Schmeling with left jabs, but Max was still confident. In the fourth round Schmeling exploited the weakness. Louis, after jabbing with his left hand, would drop that hand, exposing him to a right cross from Schmeling. Schmeling was able to knock Louis down in that round. As the round ended, Louis was obviously dazed.

While the fourth round went to Schmeling, the fifth round was the beginning of the end. At the end of the round, Schmeling once again hit Louis with a right cross. Nat Fleischer, the famous boxing writer, proclaimed, “That punch was the turning point of the fight. … [S]o powerful was that punch that it made Louis’s legs take on a rubber appearance and befuddled Joe’s brains that he never came out of the stupor.”10 Some felt that Schmeling took advantage of Louis dropping his fists thinking the round was over. From that point on, Schmeling took complete control of the fight, eventually knocking out Louis in the 12th round.

Schmeling was a national hero. On his return to Germany, he dined with Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister. Goebbels proclaimed the victory as an example of the superiority of the Aryan race. On the day after dining with Goebbels, Schmeling, along with his wife, mother, and Adolf Hitler, watched a film of the fight while eating cake.11

While Schmeling felt he was next in line to fight Braddock, that match never materialized. Between 1936 and 1938, the persecution of the Jews and others in Germany became widely known, creating significant resistance to scheduling a Schmeling title fight. Braddock’s camp also decided that by fighting Louis they would experience a greater financial reward.

Louis knocked out Braddock in the eighth round to become the heavyweight champion. After his victory, Louis stated he wouldn’t feel like a heavyweight champion until he defeated Schmeling. The stage was set for the second fight between Louis and Schmeling, which would once again be held at Yankee Stadium, on June 22, 1938.

The escalating international tension provided an electric backdrop for this second match. Austria had been annexed in March 1938. It was becoming obvious that Hitler had further territorial desires. While the resistance to Germany in America had grown, pro-German groups like the German American Bund were being heard in the United States, adding to the tense environment.

As they prepared for this second fight, both Louis and Schmeling were aware of this new dynamic. While Schmeling had received the support of many White Americans in 1936, given that Louis was African American, he was now surprised at their hostility. Reflecting on this, Louis commented that White Americans, “even while some of them were lynching black people in the South – were depending on me to K.O. Germany.”12 Two days before the fight, Schmeling received the following message from Hitler: “To the coming World’s Champion, Max Schmeling. Wishing you every success.”13 Louis summed it up best by stating, “The whole world was looking to this fight. …”14

Before the fight, Schmeling admitted being nervous in his Yankee Stadium dressing room. Louis exercised for 30 minutes instead of his normal 10 and told his handlers he was going all out for three rounds. With the preliminaries and introductions concluded, the fight was ready to begin.

Early in the first round, Louis hit Schmeling with a barrage of punches that dazed the German boxer, forcing him to grab onto the ropes. Louis then unleashed a vicious right hand that caught Schmeling in the midsection, probably his left kidney. He then proceeded to knock Schmeling down twice. On both occasions Schmeling quickly got to his feet to endure more punishment. With a third knockdown, Schmeling’s handlers jumped into the ring, forcing the referee to stop the fight. Louis’s strategy of going all out early paid big dividends.15 A column by sportswriter Grantland Rice summed it up with this succinct headline: “Louis Retains Title, Winning in First Round.”16 In a post-fight interview, Schmeling said he could not recover after the punch to the kidney.17 He was taken to a hospital, where he was kept for 10 days.

Harlem celebrated. A “Louis for President” sign was seen in an exuberant crowd on 129th Street.18 While Black America and those protesting the Nazi regime were overjoyed, Germany had seen a member of their Aryan race destroyed by the supposedly lowly Negro. On Schmeling’s return to Germany, there was no hero’s welcome.

The 1940s saw other major fights at Yankee Stadium. In 1941 Joe Louis had a title defense against Billy Conn, the light heavyweight champion, at the Polo Grounds. For 12 rounds, Conn outboxed Louis and appeared on the verge of victory. But in the 13th round, Conn got careless and Louis knocked him out. A rematch was held at Yankee Stadium after World War II. Both fighters showed their rust from the war years, but Louis prevailed, knocking out Conn in the eighth round before 45,266 fans. This was the first heavyweight title fight to be televised.

In 1947 Louis was outclassed in a title fight with Jersey Joe Walcott at Madison Square Garden in New York City. Though Louis thought he had lost the fight, he was given the victory via a split decision. Six months later, Louis fought Walcott at Yankee Stadium and knocked out Jersey Joe in the 11th round. In 1949 Louis announced his retirement but did return to fight Ezzard Charles at Yankee Stadium on September 27, 1950. Charles was recognized as the National Boxing Association heavyweight champion. Before 22,357 fans, Charles won a unanimous decision easily outpointing Louis.

While the fights that have been discussed were at the heavyweight level, bouts at other weights attracted significant interest. Middleweights Tony Zale and Rocky Graziano staged three thrilling fights in the late 1940s. The first of these was held at Yankee Stadium on September 27, 1946. Graziano seemed on the verge of victory, but Zale knocked him out in the sixth round to retain his title.

A series of four fights in the late 1940s and early 1950s between featherweights Willie Pep and Sandy Saddler excited boxing fans. The third of these was held at Yankee Stadium. Pep was unable to come out for the seventh round, and the title went to Saddler.

Another fighter who was unable to continue in a title fight was Sugar Ray Robinson. Sugar Ray, who fought mainly as a welterweight and middleweight, has been considered by many to be the greatest fighter at any weight. On June 25, 1952, he fought Joey Maxim for the light heavyweight crown at Yankee Stadium. On an extremely hot night, Robinson was unable to come out for the 14th round due to heat exhaustion, letting Maxim keep his title. Robinson also lost a fight at Yankee Stadium with Carmen Basilio.

Yankee Stadium was also the scene of three Rocky Marciano title fights during the 1950s. The first two were against former heavyweight champion Ezzard Charles. Before 47,585 fans on June 17, 1954, Marciano won a close decision. Given the closeness of the fight, Rocky gave Charles a rematch three months later, also at Yankee Stadium. This fight ended with Marciano knocking Charles out in the eighth round. Marciano then defended his title on September 21, 1955, again at Yankee Stadium, against light heavyweight champion Archie Moore. Marciano knocked out Moore in the ninth round before 61,574. Marciano retired after this fight.

As television entered more homes in the 1950s, it had a major effect on boxing attendance. In the New York City region, you could watch boxing on television on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday nights. While major heavyweight fights still drew large crowds, small fight clubs suffered. However, options to show major matches on television grew, and its impact would be felt.

After Marciano vacated his title, Floyd Patterson became the heavyweight champion. On June 26, 1959, Ingemar Johansson, a Swede, won the title at Yankee Stadium with a technical knockout in the third round after Patterson was knocked down seven times during the round. The attendance was a disappointing 18,215 fans. However, the fight was widely shown on closed-circuit TV, and brought in additional revenue of over $1 million.19 The impact of such an option meant large venues like Yankee Stadium were no longer needed to attract large gate receipts.

The 1960s saw Muhammad Ali burst on the scene, winning the title when Sonny Liston did not answer the bell for the seventh round. Ali was later stripped of his title when he was convicted of draft evasion. He claimed he was a conscientious objector, and his conviction was overturned by the United States Supreme Court. After three fights with Joe Frazier, Ali defeated heavyweight champion George Foreman via a decision in the “Rumble in the Jungle” fight in Zaire.

The recently renovated Yankee Stadium saw its last heavyweight title fight with Ali fighting Ken Norton on September 28, 1976. Before Ali won the title against Foreman, he had split two fights with Norton. In this third fight, Ali won a contested decision with many writers thinking Norton won. Bob Arum, the promoter, stated that while over 30,000 tickets were sold in advance, the real attendance was only about 19,000.20 New York City was in the midst of a police strike, which held the crowd down and limited the number of walkups to an estimated 10.21 This was the last fight to be held at the original Yankee Stadium.

On June 5, 2010, boxing was back, but at the new Yankee Stadium, opened in 2009. Bob Arum promoted a boxing card featuring Miguel Cotto fighting Yuri Foreman for the World Boxing Association super-welterweight title. Before over 20,000 fans, Cotto stopped Foreman in the ninth round to win the title. Since then, no boxing matches have been held at Yankee Stadium.

Since its opening in 1923, the original Yankee Stadium was the scene for 30 championship fights. Of those 30, it was the heavyweight contests that attracted the most fans and excitement. The two Joe Louis-Max Schmeling matches, even though the first was not for the championship, are unforgettable. The second has become known as the fight of the century. These were not just fights between two boxers, but contests between an American Negro and a member of Aryan Germany. As such, they became politically significant, given what was happening on the world stage in the 1930s. These two fights and the role Yankee Stadium played will always be remembered.

DR. JOHN J. BURBRIDGE JR. is professor emeritus at Elon University, where he was both a dean and professor. While at Elon he introduced and taught Baseball and Statistics. He has authored several SABR publications and presented at SABR conventions, NINE, and the Seymour meetings. He is a lifelong New York Giants baseball fan. The greatest Giants-Dodgers game he attended was a 1-0 Giants victory in Jersey City in 1956. Yes, the Dodgers did play in Jersey City in 1956 and 1957. John can be reached at burbridg@elon.edu.

NOTES

1 Dempsey-Carpentier Fight, https://njcu.libguides/dempsey, March 18, 2022.

2 Dempsey-Carpentier Fight.

3 Lyle Spatz and Steven Steinberg, 1921: The Yankees, The Giants, and The Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 34.

4 Spatz and Steinberg, 33.

5 Spatz and Steinberg, 34.

6 Dan Steinberg, “The Best Boxers, the Grandest Stage,” Wall Street Journal, May 27, 2010. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704226004575262652086100516.

7 Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-nuremberg-race-laws

8 Lewis A. Ehrenberg, The Greatest Fight of Our Generation: Joe Louis versus Max Schmeling (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 89.

9 Ehrenberg, 88.

10 Ehrenberg, 90.

11 David Margolick, Beyond Glory: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling and a World on the Brink (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 182.

12 Ehrenberg, 138.

13 Ehrenberg, 141.

14 Ehrenberg, 138.

15 Jesse A. Linthicum, “Louis Follows Orders to Letter to Retain Title in One Round,” Baltimore Sun, June 23, 1938: 10.

16 Grantland Rice, “Louis Retains Title, Winning in First Round,” Baltimore Sun, June 23, 1938: 1.

17 “Punch to Body Won, Says Joe,” Baltimore Sun, June 23, 1938: 10.

18 “Harlem Booms Joe Louis for U.S. President,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 2, 1938: 15.

19 Bert Randolph Sugar, “Greatest Knockouts: Patterson vs. Johansson,” ESPN.com, September 26, 2006. https://www.espn.com/sports/boxing/news/story?id=2606226.

20 Bernard Fernandez, “Muhammad Ali-Ken Norton 3: Chaos at Yankee Stadium 45 Years Later,” Ring TV, September 28, 2021, https://www.ringtv.com/627543-muhammad-ali-ken-norton-3-chaos-at-yankee-stadium-45-years-later/.

21 Michael Woods, “The Real Action Was Outside The Stadium,” ESPN, March 28, 2010. https://www.espn.in/news/story?id=5230628. Accessed October 18, 2022.