Broadcasting Red Sox Baseball: How the Arrival of Radio Impacted the Team and the Fans

This article was written by Donna L. Halper

This article was published in Fall 2017 Baseball Research Journal

In the early years of the American League, Boston fans had a lot to smile about—World Series victories in 1903, 1912, 1915, 1916, and 1918—but after that, everything changed for the worse. Not only was Babe Ruth infamously sold, but the Red Sox began a string of losing seasons. Faced with teams that seldom left the cellar, fans tried to find reasons for hope—occasionally, the team would get timely hits or win a double-header1—but with no chance of a pennant in sight, attendance at Fenway Park suffered.2

But even in good times, only a small number of fans could watch a game in person. During the team’s winning years, the games at Fenway Park were often sold out (although not in the 1918 World Series)3 and even when there were seats available, many fans couldn’t get the day off from work to attend, or couldn’t afford the tickets. Although ticket prices cost far less in 1918 than today, they were still an extravagance for many working-class people. Day-of-game box seats for the 1918 World Series were being sold for $3.30, grandstand seats for $1.65, and pavilion seats $1.10.4 To put those prices in perspective, the average annual family income in Boston around that time was $1,477, or about $28 a week.5 The City of Boston’s Official Record showed that stablemen, watchmen and janitors were making $3 a day, while plumbers and machinists received $3.50 to $4 a day.6

Whether rich or poor, fans all had the same problem: if they couldn’t be at Fenway Park—or if the team was on the road—getting up-to-the-minute information was nearly impossible. In the 1910s, there were a limited number of ways to find out what was going on. Fans had to rely on their local newspaper, which would publish multiple editions throughout the day and into the evening as they received reports by telegraph from the ballpark. During the World Series, as each game progressed, the latest score was posted on the front page, at the top, in bold type.

The most enthusiastic fans in the Boston area would make a pilgrimage to lower Washington Street’s “Newspaper Row.” One of Boston’s busiest thoroughfares, Newspaper Row was home to the Boston Globe, the Boston Evening Transcript, the Boston Post, the Boston Daily Advertiser, the Boston Evening Record, and, until it went out of business in 1917, the Boston Journal. Herbert Kenny worked for two of the papers (the Post and the Globe). In his 1987 book about Newspaper Row, he compared lower Washington Street to the ancient Greek agora, an open meeting place that served as the center of public life.7 Fans would gather to socialize and talk sports while eagerly awaiting the scores, or hoping one of the sportswriters might come by and chat. As soon as any information became available by telegraph, newsboys would write it on chalkboards, which were positioned in front of the offices of the Globe, the Post, and several others. Sometimes results would be announced by megaphone. Fans would cheer loudly each time the news was good.8

But although the Red Sox teams of the 1920s weren’t giving fans many reasons to cheer, an easier way to find out what was happening at the ballpark was emerging. An amazing technology called radio made its debut in the summer of 1920, a life-changing invention for anyone who loved sports. (Even though many textbooks have perpetuated the myth that KDKA in Pittsburgh was the first radio station, and that its November 2, 1920, broadcast of the presidential election returns was the first broadcast, neither of these claims is true.9 There were stations on the air months before KDKA, including one each in greater Boston, Detroit, Montreal, and Madison, Wisconsin.)

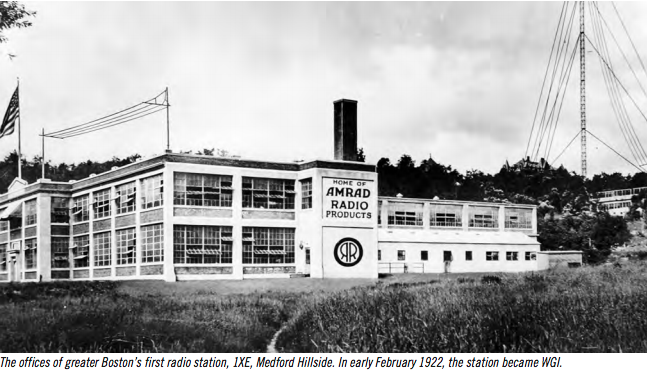

In 1920 and 1921, greater Boston only had one radio station—its name was 1XE (the X meant the station was considered experimental, which is what most people thought radio was back then). 1XE only had about fifty watts of power. Owned by a local company called AMRAD, its studios were located at Medford Hillside, near what is today Tufts University, about five miles from downtown Boston. The far bigger and better-known WBZ, owned by Westinghouse, would go on the air in mid-September 1921 in Springfield, about 85 miles from Boston. WBZ did not open a Boston studio until early 1924.

In 1921, radio wasn’t even called radio—most newspapers called it either the “wireless telephone” or the “radiophone” and there were only a handful of stations nationwide—no more than fifteen commercial stations on the air in the entire United States. But despite the fact that only about 2000 people in greater Boston owned radio sets in 1921, radio was already doing amazing things for baseball fans.10 In October, the World Series was broadcast; KDKA was one of the stations that provided listeners with the opportunity to hear this important sporting event.11 For the first time, fans who lived far from New York, where the games were taking place, could follow the play-by-play in real time, as if they were actually there, and not merely following a recreation. Radio was the first mass medium to provide real-time access to an event as it was happening. For those unable to receive the game from the few stations broadcasting it, ham radio operators stepped up, relaying the scores from the ballpark to anyone who wanted them.12

By the summer of 1922, the radio craze was sweeping the country, and several hundred new stations went on the air. Among them was WNAC, owned by Boston department store owner John Shepard III. He installed a studio for his new radio station in the Shepard Department Store in downtown Boston. His brother Robert ran the Shepard Department Store in Providence, which became the home of station WEAN. Many stations provided up-to-date sports scores on a regular basis.13 A small number of stations also experimented with remote broadcasts, occasionally putting sporting events on the air live, including boxing matches and the 1922 World Series.

The games were once again on the air from New York, but this time the Series had a much larger radio audience. By some accounts, about five million people tuned in, and fans on three continents heard the broadcasts.14 Radio was also a democratizing influence, bringing the same broadcast to listeners regardless of race. Unfortunately, not only were all the major league teams segregated, so were some of the ballparks. White fans often received far better seating than black fans, some of whom were only allowed to sit in the bleachers.15

Though only a limited number of baseball games were broadcast in 1922, a few baseball stars were beginning to do radio interviews, and even give talks. Among them was Babe Ruth, who spoke on Denver station KFAF in late October 1922.16 (Ruth also gave a radio testimonial during the 1928 presidential election—he was an enthusiastic supporter of Democratic candidate Al Smith. The Babe took part in a broadcast on behalf of the New York governor, whom he called “the greatest friend of American sports.”17 Despite the Babe’s kind words, Smith lost to Herbert Hoover.)

The public’s love affair with radio put the newspapers in an awkward position: as interest in radio expanded, many print publications worried that the new mass medium would take people away from reading the paper. Editors were unsure what to do about radio—should they ignore it or should they embrace it? Some tried to pretend radio didn’t exist, refusing to write about it or mention it. Others hired someone with ham radio experience to write columns of a mainly technical nature, and occasionally comment about what was on the air at a local station. But a few newspaper editors saw real potential in aligning their publication with a radio station; they wanted to use radio to promote their reporters, the way the Detroit News did with their pioneering station 8MK/WWJ. In greater Boston, the Boston American was the first to make such an agreement. In mid-February 1922, reporters from that newspaper began working with WGI (formerly 1XE), making it possible for listeners to hear daily news reports, sports scores, and other information.

The newspapers needn’t have worried about losing readership; sports fans wanted more, not less, information. Baseball fans still wanted to read their favorite baseball writers, to get analysis, and they still enjoyed their favorite sports cartoonists—every major newspaper had at least one. The Boston Traveler was the sister paper to the Boston Herald, and one of the first of the dailies to enthusiastically embrace radio, providing coverage of the new mass medium beginning in February 1921. The Traveler hired its own radio editor, Guy Entwistle, and he wrote a column about it three times a week. (Three years later, both the Herald and the Traveler would become even more involved with radio: they entered into an agreement with WBZ, when the Westinghouse station opened a Boston studio in early 1924.) The Traveler was known for its hard-working sports staff. Among the writers who covered baseball was Augustus J. Rooney—better known as Gus, but using the byline “A.J. Rooney” at that time. He covered college sports when baseball was not in season. And the Traveler had two sports cartoonists—Abe Savrann, who signed his work SAV, and Charles (Charlie) Donelan, who also wrote an occasional sports column. Both Gus Rooney and Charlie Donelan would soon become very important in the history of baseball on the radio in Boston, while Abe Savrann would play a part in (perhaps) solving a long-time mystery: who was the play-by-play announcer of the first baseball game to be broadcast on Boston radio?

Some of the earliest interactions between the Red Sox and radio occurred in 1923. No, the games weren’t on the air (which, given yet another losing season, was probably a good thing), but for perhaps the first time, the manager was. That courageous gentleman was the newly hired Lee Fohl. A former catcher who had only played five major league games, Fohl had managed successfully in the minors, as well as for the Cleveland Indians and St. Louis Browns, before being named Red Sox manager for the 1924 season, succeeding Frank Chance.

Fohl was optimistic about his new job in Boston—in fact, not long after he was hired, he was scheduled to give a radio talk about the upcoming season, via the Shepard station, WNAC. On November 7, 1923, not long after he arrived in Boston, he was introduced to the local baseball writers. His talk was called “The Red Sox Prospects for 1924.”18 Unfortunately for modern-day historians, no recording exists of the broadcast; in fact, there are very few recordings from broadcasting’s first decade. Audiotape had not yet been invented and even electrical transcriptions did not make their debut until 1929.19 Some newsmakers, such as an influential member of Congress or the president, might have made a phonograph record of an important speech, but it would not have been cost-effective or easy to do this for a baseball game (or most other sporting events of that time). Thus, while you may hear some (allegedly) early broadcasts online, many of them are reenactments, since few if any actual 1920s sports broadcasts were ever recorded or preserved.20 Fohl’s willingness to go on the air was somewhat out of character for him, and not just because radio was new.21 By most accounts, Fohl didn’t like the limelight.22 It was probably exciting for the fans to hear from Fohl, in his own voice—in an era when access to newsmakers was limited. Under Fohl’s leadership there was a slight improvement in how the team did: the Red Sox left the cellar and finished seventh in 1924.

There were still no local broadcasts of Red Sox games in 1923 or 1924. In early October 1924, Boston’s newest station, WEEI (owned by the Edison Electric Illuminating Company), had arranged to link up with New York station WEAF to broadcast the first game of the World Series from Washington, as the Nationals battled the Giants.23 The play-by-play announcer would be Graham McNamee, a name and voice very familiar to fans in many cities, Boston among them. Because the 1920s were a time when DXing (listening for distant stations) was a popular pastime for anyone who owned a radio, it was not uncommon for fans in one city to listen to broadcasts from other cities. WEAF’s signal was easily heard in Boston. Local baseball fans had discovered WEAF broadcasting some New York Giants games, and even though they weren’t supporters of that team, they enjoyed hearing a ballgame on the radio. And they especially enjoyed Graham McNamee’s announcing; reporters and fans alike praised him.24 McNamee was already a radio veteran by 1924, having announced the 1923 World Series along with sportswriter William McGeehan. Despite not being local, McNamee became so popular as a sports broadcaster that greater Boston charities invited him to be their guest speaker.25 The versatile radio star also came to Boston to perform as a vocalist. A talented baritone, he sang at Symphony Hall in December 1925 before a large and appreciative audience.26

For those eager to hear local baseball on the radio, things progressed in 1925. The Red Sox still weren’t winning, and the games still weren’t being broadcast, but something new came to Boston radio: baseball talk. Earlier, I mentioned a popular sports cartoonist for the Boston Traveler, Charlie Donelan. But he was more than a cartoonist and an occasional sports columnist, he was also a story-teller and a comedian. Donelan had brought his comedy act to many local vaudeville theaters and civic events, and he had even performed on several Boston radio stations. (He was known for his fictional character “Russett Appul.”) In early April 1925, Donelan received a new opportunity: he got his own sports-talk radio program on WEEI. Twice a week during much of 1925, Charlie would talk baseball and give fans inside tips, as well as discussing people he had met while covering all the teams.27

By most accounts, WBZ seems to have aired the first live baseball in Boston, but it wasn’t a Red Sox game. Rather, the station broadcast the opening game of the Boston Braves season from Braves Field on April 14, 1925. As I mentioned earlier, one of the mysteries about that game is who did the announcing. I am WBZ’s unofficial historian and I was given some of the station’s archival notes compiled by the late Gordon Swan, whose long career with the station included being an announcer and production manager at WBZ Radio, and later a program director during the early years of WBZ-TV. But while the notes list WBZ’s accomplishments year by year beginning in 1921, and state that WBZ’s Boston studio was first to broadcast a baseball game, the announcer’s name is curiously omitted. It is also omitted from the few newspaper mentions of the event—including the Herald and Traveler, the two publications aligned with WBZ back then.

Some people have suggested that the announcer might have been Charlie Donelan, but I have found no evidence to support that theory. Donelan did broadcast Braves games later that year, but over station WNAC.28 And that brings me to SAV, Boston Traveler sports cartoonist Abe Savrann. Born in Russia as Abraham Savransky in 1898, he and his family emigrated to the United States in 1902. A talented illustrator even in his teens, he graduated early from Rindge Technical High School in Cambridge, and was immediately hired by the Boston Post in March 1916.29 He then joined the Traveler circa 1918, covering news and sports, and he was still there when the baseball season opened in 1925.

Fast forward to 2016, as I pored over microfilm of the Traveler in preparation for a talk about sports cartoonists (much of the Traveler still isn’t digitized). I found a cartoon of SAV’s from April 15, 1925, showing the highlights of the Braves home opener. In that pre-television era, sports cartoonists often provided these highlights for those who couldn’t attend the game in person. The last panel of the cartoon praised Joe E. Brown for having announced the game on WBZ. Brown was a big name at that time, a popular vaudeville and film comedian who had played baseball prior to his entertainment career; he wasn’t a local to Boston nor a WBZ employee, but at a time when there was no official play-by-play announcer for either Boston team, it would not have been unusual for a celebrity, a businessman, or a local print reporter, to give broadcasting a try.

Could Brown have been that mystery announcer? Abe Savrann knew Brown personally, and the Elks Lodge to which SAV belonged was about to honor Brown; in fact, SAV was on the committee that arranged the event.30 Also, Brown was in the Boston area during the week of that Braves game—he was starring in the live stage performance of “Betty Lee,” which opened on April 11, 1925 at the Majestic Theatre. Thus, the last panel of SAV’s April 15, 1925, Traveler cartoon about the Braves game may have solved the mystery. The caption reads, “the inimitable Joe E. Brown broadcast the game for WBZ.” It’s not definitive proof, but circumstantially at least, it does look like Brown was the person who did the play-by-play.

When WNAC got permission to air other Braves games in 1925, this was considered very controversial by some of the teams, who feared that making baseball available on radio would cause attendance at the games to decrease. As with the fears of newspaper owners that radio would make fans lose interest in reading the paper—which did not happen—the fears of team presidents were equally overblown; fans who could attend did so, and everyone else appreciated being able to follow the game. (In fact, in the decades since the portable radio was invented, fans have done both, bringing a radio to the park to listen to the play-by-play during the game.) Once the details on permission to broadcast were worked out, the first announcer WNAC used was Benjamin R. Alexander (newspapers incorrectly said Benjamin H). Alexander was not an announcer per se—in fact, he had a long career working for the Chamber of Commerce, which sponsored the first game on WNAC. Subsequently, the Braves games were announced by Charlie Donelan. Like McNamee, Donelan was praised by local reporters for being knowledgeable and enthusiastic. Fans seemed to agree, and attendance at his talks and appearances continued to increase.

Red Sox fans were still waiting patiently. Those who had a good radio tuned in to stations in other American League cities, because sometimes those stations broadcast a game where their team was playing against the Sox. WRC in Washington, DC, then affiliated with the Washington Times newspaper, broadcast some of the Washington Nationals’ road games, and that included a three-game series versus the Red Sox at Fenway Park in early October 1925.31 The Nationals had already won the pennant, and didn’t play like champs.32

It is not surprising that WNAC got permission to broadcast the Red Sox games in 1926. Station owner John Shepard III loved sports, and he loved radio; he also loved being in the limelight. Once again, when seeking an announcer, Shepard turned to the Boston Traveler, where Gus Rooney still worked. Gus had tried his hand at broadcasting when he announced a boxing match, so Shepard asked if he wanted to be the announcer for the Red Sox opener on April 13, 1926. Gus agreed, but had he known what he just signed up for, he might have asked for combat pay. The weather was windy and cold, and the Red Sox were just as miserable, trailing early 11 to 1, causing many fans to head for the exits. But Gus persisted in trying to make the game interesting for the WNAC audience. He told stories of the old days, he discussed baseball strategy, and in the late innings the Sox began to mount a comeback. While they came up short in the end—losing 12–11 to the Yankees—it turned out to be an exciting game after all. Unlike today when a play-by-play announcer has assistants and sidekicks, Gus Rooney had nobody; the game dragged on for three hours, during which he was the only person talking. His colleagues at the Traveler noted that the next day, he was so hoarse he could barely speak at all.33 That didn’t stop him from doing several other ballgames in subsequent weeks; throughout much of 1926 he could be found doing play-by-play, although more often for the Braves.

Back on Newspaper Row, newspapers were still trying to figure out how to integrate the public’s interest in listening to the games with reading about sports. By the time of the 1926 World Series, radio coverage had continued to expand. That year, the games could be heard on a 21-station chain which covered much of the East and Midwest: WEEI in Boston, WTAG in Worcester, and WJAR in Providence, through the courtesy of flagship station WEAF in New York. The announcers were Graham McNamee and Phillips Carlin.34 With no Boston team in the Series, and the games being broadcast on radio, crowds were smaller on Newspaper Row, and as a Globe reporter noted, fans seemed “quiet” and “apathetic,” even though about a thousand still gathered. The Globe had its own radio studio, and it re-broadcast the game; but the newspaper also had Frank Flynn, an experienced telegrapher, ready to step in, just in case WEEI’s signal failed (signals that faded in and out were a constant problem in early broadcasting). An employee with a megaphone was also ready to shout out the scores. Megaphone and telegraph weren’t necessary—the “modern” technology worked fine, although the crowd was as fascinated by how quickly the telegrapher could send and receive information as they were with the game itself.35

Meanwhile the Red Sox continued to lose. Lee Fohl’s tenure as manager continued through 1925 and ’26, two more years in last place. Fohl was then replaced by Bill Carrigan. This was a very popular decision with the fans, who remembered Carrigan’s successful tenure managing the Sox 1913–16. Carrigan had left baseball and gone home to Lewiston, Maine, where he had an equally successful career as a banker, but Red Sox owner Bob Quinn lured him out of retirement.36

Of course, the Red Sox lack of improvement had been a constant topic in all of the Boston newspapers, and by 1927 hearing the manager or a well-known sportswriter opining on the season was becoming a radio staple. On April 13, 1927, Boston Globe sportswriter Melville E. Webb Jr., who had been covering baseball for several decades, gave a talk about the Red Sox via WNAC. He acknowledged that Carrigan had “no easy task” ahead of him; in fact, Webb noted that it was unclear what Carrigan could do to improve the Red Sox’ fortunes. He was unfortunately correct. Carrigan didn’t do much better than Fohl—in 1927, the Sox finished fifty-nine games out of first (and would continue in last place 1928–29 under Carrigan).

There is little debate among Boston media historians that the first local baseball announcer to gain a huge following was Fred Hoey. However, there is some debate about when he first began broadcasting the games—some sources say 1926, although I have found little evidence of that. Most modern scholars, including Curt Smith, believe that he was on the air doing Boston Braves home games beginning in 1927; it would be a few more years before road games would be broadcast.38 Hoey was not the only sports announcer at WNAC that year. Gerry Harrison also did play-by-play for some of the Braves games, and announced some Red Sox baseball too.39 Harrison had worked at WLEX in Lexington, Massachusetts, and was experienced at announcing hockey, boxing, football, and even professional wrestling.40 (WLEX is long since defunct, and its call letters eventually ended up in Lexington, Kentucky.) Harrison went to work for John Shepard III, who, by that time, owned other stations; Gerry Harrison later became general manager of radio station WLLH in Lowell, Massachusetts.

But by 1928, it was Fred Hoey who was usually behind the microphone whenever there was a baseball game at either Fenway Park or Braves Field. Hoey was already becoming Boston’s best-known and most trusted baseball announcer, even though as a young man, his passion had been hockey.41 He played forward for a local amateur team, and later did some managing; he also wrote about schoolboy sports for the Boston Herald, before finding a new career doing baseball play-by-play on radio. During the 1928 season, he announced both the Braves and Red Sox home games on WNAC, while Gerry Harrison focused on broadcasting college sports, especially football and hockey.

Whether the Red Sox were winning or losing (and in the 1920s, they were usually losing), Hoey made the games come alive. Fans adored him—especially female fans, who found his explanations of baseball’s finer points both understandable and interesting. Some reporters believed it was thanks to Hoey that more women were coming to the games.42 Given his popularity, Fred was asked to expand his role at WNAC, the way Charlie Donelan had done in 1925. Donelan by this time had gone back to reporting and cartooning, and he was still a popular guest speaker. His grandson noted, when I spoke with him in early January 2016, that Charlie’s eyesight was never very good; perhaps he realized he would be more effective as a cartoonist and an entertainer, rather than sitting in the press box trying to report on what was happening down on the field. As for Gus Rooney, whose eyesight was fine, he too had returned to print journalism—interestingly, he would eventually go into the public relations field. When the new Suffolk Downs racetrack opened in 1935, Gus was their publicist.43

Fred Hoey debuted his own sports-talk program on WNAC on May 10, 1928. One of his first guests was Sox manager Bill Carrigan, who discussed the outlook for the season. Carrigan was no stranger to radio. He was a big fan, and back home in Maine, he and his family enjoyed listening to their favorite program. In December 1926, he had been part of a charitable event that was broadcast by WEEI, raising money for disabled veterans.44 Hoey told the press that he planned to have weekly interviews with other members of the teams and his next one, the following week, was with Red Sox pitcher, and Massachusetts native, Danny MacFayden.45

But as mentioned earlier, while we can read the newspaper and magazine accounts of that era, it is disappointing that few of these early programs have survived. We have no idea how most of the early announcers sounded. Some audio of a few 1930s baseball broadcasts are found on YouTube. One recording features Fred Hoey announcing the 1936 All-Star game, along with the Yankee Network’s Linus Travers. Although the quality is poor by today’s standards, it provides an inkling of how the games sounded. Curt Smith has interviewed several veteran broadcasters who grew up listening to Fred Hoey. Ken Coleman recalled that his name recognition was very high—it seemed just about everyone, fan or not, knew who he was; Coleman also remembered Fred’s ability to convey a love and respect for the game, even though he used an understated style that was never flamboyant or showy.46 Hoey’s player interviews also seem to have been well-received, and soon he was interviewing members of the Boston Braves, in addition to the Red Sox.47

Newspaper Row was still a gathering place for big news events throughout the 1920s, but there were fewer times when baseball brought out the large crowds. People gathered to find out election results and in September 1926 the Globe broadcast updates from the heavyweight championship boxing match between Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney. Locally, the match was heard on both WBZ and WEEI, but many fans (some estimates said as many as ten thousand) still preferred to gather in Newspaper Row to listen to the updates as they were broadcast by the Globe’s radio service, with reporter Willard DeLue doing the local announcing, augmenting network coverage by Graham McNamee.48 Perhaps with the Red Sox doing so badly, and the Braves not doing well either, few baseball fans were motivated to make the trip to Newspaper Row. It was sufficient to listen at home to the broadcasts that could be heard from various cities, enjoy the speculation and the interviews, and wonder when, if ever, the team would turn things around.

In late 1926, the National Broadcasting Company (today known as NBC) made its debut—the first national radio network. By September 1927, there was a second when the Columbia Broadcasting System (today known as CBS) got up and running. This was wonderful news for baseball fans, since there were now two equally good options for hearing the 1927 World Series. NBC went with its well-tested and much-loved duo of Graham McNamee and Phillips Carlin, heard in Boston on both WEEI and WBZ, while CBS utilized their own veteran sports announcer J. Andrew White, heard in Boston on WNAC. Radio sports were now well accepted. By some estimates, more than twenty million people tuned in for the first game of the 1927 World Series, listening via the fifty-three network-affiliated stations that carried the games (forty-three on NBC and ten on the much newer CBS).49 It was a far cry from the 2,000 listening in greater Boston back in 1921, and further proof of how important radio had become in a relatively short time.

Being able to hear a few games on the air did not discourage fans from coming out to Fenway Park; a losing team did that. Low attendance meant the Sox lost money throughout most of the 1920s.50 One thing the Red Sox hoped would boost attendance a little was the arrival of Sunday baseball. Boston’s influential clergy had long opposed allowing baseball to be played on the Sabbath, even though many in the public would gladly have attended on their day off from work.51 Just before the start of the 1929 season, both the Red Sox and Braves received the okay to play on Sunday.52 Fred Hoey was scheduled to broadcast when the Braves played the Giants on Sunday, April 21, but the game was rained out; he later broadcast several other Sunday Braves and Red Sox games. Unfortunately, being on the air on Sundays didn’t help either team’s fortunes. The Red Sox ended up 58–96, and the Braves, 56–98. And as it turned out, despite Sunday baseball, attendance went down in 1929.

From the perspective of the devoted Red Sox fan of the 1920s, it may have been a decade to forget; but from the perspective of media historians, it was truly a transformational decade. Thanks to the arrival of radio, fans who could not get to the ballpark could still enjoy a game in real time, from the comfort of their home; they could also hear their favorite players being interviewed, and listen to analysis from baseball experts. The arrival of the National Broadcasting Company and the Columbia Broadcasting System, the first national networks, meant the great announcers from various cities could also be heard in Boston, as could the World Series, no matter where it was being played. During the 1920s, play-by-play announcing became an art form, appreciated in cities from coast to coast. Whether it was a local announcer like Fred Hoey, or nationally-known network announcers like Graham McNamee, Major J. Andrew White, or Edward “Ted” Husing (two veteran broadcasters who worked for CBS), experienced professionals could describe the scene at the ballpark so realistically that listeners felt they were there. Graham McNamee became so well-known nationally that he made the cover of Time magazine. Years later, his distinguished career, which included broadcasting the World Series for twelve consecutive years (1923–34) and being the network announcer during such major news events as Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight, earned him the 2016 Ford C. Frick Award.53

The growth in availability of baseball broadcasts throughout the 1920s meant one other thing changed—the expectations of the audience. In 1921–22, baseball broadcasts were a novelty, offered by only a handful of stations, and heard by very small numbers of listeners. No one expected a smooth and professional sound; the announcers were as new to it as the listeners. Ongoing technical difficulties were also part of the radio experience in those early years. Listeners were often frustrated by static caused by atmospheric interference, or distant signals suddenly fading out (usually at a critical time in their favorite program). Even the best engineers of the early 1920s were unsure whether this could be prevented.54 But while these problems were annoying, they were bearable, and most listeners were grateful for the entertainment and information their radio provided. By 1929, the technology had improved considerably. And the existence of two national radio networks, along with hundreds of local stations, meant listeners from coast-to-coast regularly had access to the biggest newsmakers and most famous performers. Baseball fans grew accustomed to hearing the games broadcast by talented and experienced announcers.

But what hadn’t changed was the fans still appreciated being able to read about their favorite players in the local newspapers. In fact, it was still a golden age for sports journalism, and every city had its own well-regarded reporters. In Boston, as elsewhere, baseball cartoons were popular; by the end of the 1920s Gene Mack of the Boston Globe and Bob Coyne of the Boston Post were receiving the most acclaim. Many popular baseball reporters provided thorough analysis of every game, including Jim O’Leary of the Boston Globe, Paul “Herbie” Shannon of the Boston Post, and Burt Whitman of the Boston Herald. There was little if any animosity between the sportswriters and the broadcasters. In fact, in 1931, when Fred Hoey was honored, Bob Coyne created a cartoon tribute to Fred’s career, and several sportswriters praised his outstanding work.55,56 Fans of the late 1920s still made the pilgrimage to Newspaper Row now and then, hoping to meet one of the writers and talk some baseball. But by this time, standing out on Lower Washington Street had been replaced by sitting in the comfort of the “radio room” and waiting for the game to begin.

DONNA L. HALPER, Ph.D is a media historian, author of six books and many articles (including chapters in a number of SABR books). A former broadcaster and journalist, she is an Associate Professor of Communication and Media Studies at Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Notes

- James O’Leary. “Baseball Glory That Once Was Boston’s Returns for Day at Least.” Boston Globe, July 18, 1926: B14.

- “Sunday Baseball Fails to Rescue the Boston Red Sox From the Cellar in 1929.” http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/sunday-baseball-fails-to-rescue-the-boston-red-soxfrom-the-cellar-in-1929.

- https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1918_World_Series.

- “Sox Series Ticket Plans Call for 19,000 Rush Seats Daily.” Boston Herald, August 29, 1918: 4.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 100 Years of Consumer Spending. https://www.bls.gov/opub/uscs/1918-19.pdf: 10–11.

- City Record of the City of Boston, 1917–1918. (Vol 9, #1): 440–41.

- Herbert Kenny, quoted by Charles Fountain. New England Quarterly, vol. 61, #2 (June 1988): 300.

- “Big Crowd Looked for at Games at Boston.” Evansville (IN) Courier and Press, September 8, 1918: 21.

- For more about the KDKA myth, see Zack Stiegler. “Radio Revisionism: Media Historiography and the KDKA Myth.” Journal of Radio and Audio Media (Vol. 15, #8), 2008: 90–101.

- “Curley to Speak Over Radiophone.” Boston Herald, December 3, 1921: 2.

- “Radiograms.” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 13, 1921: 9.

- “Get Scores by Wireless.” Trenton (NJ) Evening Times, October 11, 1921: 3.

- See for example the radio listings for WBZ in Springfield. According to the Springfield (MA) Daily News, May 22, 1922: 12, WBZ’s evening schedule featured musical selections, an educational talk, and a bedtime story for the children; and it also featured regular updates of American League, National League, and Eastern League scores.

- Danielle Sarver Coombs and Bob Batchelor. American History Through American Sports (Santa Barbara, California: Praeger, 2013): 23.

- Sarah L. Trembanis. The Set-Up Men: Race, Culture and Resistance in Black Baseball (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2014): 33.

- “Babe Ruth to Talk Over KFAF Radio.” Denver Post, October 9, 1922: 10.

- “Babe Praises Al in Radio Address.” (Little Rock) Arkansas Gazette, October 20, 1928: 10.

- “Radio Listings,” Boston Herald, November 7, 1923: 8.

- “Programs by New Process.” Charleston (SC) Evening Post, January 11, 1929: 13.

- Christopher H. Sterling and Cary O’Dell, editors. “Documentary Programs.” Concise Encyclopedia of American Radio (New York: Routledge, 2010): 223.

- Nell Ray Clark. “How They Behave in Presence of Mike.” Seattle Sunday Times, June 23, 1929: 60.

- “Fohl Likely to Move Over Boston Way in Spring.” Charlotte (NC) Observer, August 5, 1923: 1.

- “World’s Series Broadcast.” Boston Globe, October 3, 1924: 22.

- “McNamee Popular Announcer at WEAF.” Boston Globe, November 21, 1924: 24.

- “Graham McNamee in Brockton April 30.” Boston Globe, April 26, 1926: 15.

- “McNamee in Concert at Symphony Hall.” Boston Herald, December 3, 1925: 10.

- “Sport Talks by Charlie Donelan.” Boston Herald, April 13, 1925: 5.

- See, for example, “Radio Broadcasts.” Boston Herald, July 16, 1925: 20.

- “Small Class at Rindge Technical.” Cambridge (MA) Chronicle, June 17, 1916: 11.

- “Rousing Reception to Be Tendered to ‘Joe’ Brown.” Cambridge (MA) Chronicle, April 11, 1925: 5.

- “Radio Show Visitors to Hear Ball Game.” Washington (DC) Times, September 30, 1925: 5.

- The Senators sat out many of their starters in the first game, much to the consternation of the Boston baseball writers. Even when a few of the regulars played in game two, the Senators didn’t field well, and failed to get any timely hits. Amazingly, for the second day in a row, the Red Sox managed to defeat them. The third game was rained out, but at least the season ended on a positive note, in a year when the Red Sox lost 105 and won only 45. Melville E. Webb Jr. “Fans Don’t See Real Champions Here.” Boston Globe, October 1, 1925: 23.

- “Gus Rooney’s Larynx Gets a Workout.” Boston Traveler, April 14, 1926: 16.

- “21 Stations Will Broadcast Series.” Boston Globe, September 30, 1926: A14.

- “Interested but Far from Excited Crowd Hears Globe’s Story of the Game.” Boston Globe, October 3, 1926: B21.

- James C. O’Leary. “Carrigan to Manage Red Sox.” Boston Globe, December 1, 1926: 1, 13.

- “Melville E. Webb Jr. of Globe Gives Radio Talk on Baseball Campaigns.” Boston Globe, April 14, 1927: 28.

- Curt Smith. Mercy!: A Celebration of Fenway Park’s Centennial Told Through Red Sox Radio and TV (Washington DC: Potomac Books, 2012): 239.

- “What’s on the Air?” Boston Globe, April 21, 1927: 22.

- “On the Air: Radio Listings.” Boston Herald, November 13, 1929: 26.

- “Franklin A.A. Ice Hockey Team.” Boston Journal, January 3, 1905: 4.

- “First Baseball Game Saturday.” Boston Herald, April 7, 1929: 38.

- John Fenton. “25,000 Get Preview of Suffolk Downs.” Boston Herald, July 8, 1935: 1, 7.

- Burton Whitman. “Carrigan to Talk Over Radio.” Boston Herald, December 17, 1926: 18.

- “What’s on the Air?” Boston Globe, May 10, 1928: 29.

- Curt Smith. Mercy!: A Celebration of Fenway Park’s Centennial Told Through Red Sox Radio and TV (Washington DC: Potomac Books, 2012): 31.

- “What’s on the Air?” Boston Globe, June 14, 1928: 29.

- “10,000 Fans Stand in Front of Globe Office in Drizzle and Hear Broadcast of Fight.” Boston Globe, September 24, 1926: 1.

- “Radio Story Heard by 20,000,000.” Boston Globe, October 6, 1927: 15.

- Donald G. Kyle and Robert B. Fairbanks, eds. Baseball in America and America in Baseball (College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 2008): 101.

- More about the battle over Sunday baseball can be found in Charlie Bevis’s journal article “Rocky Point: A Lone Outpost of Sunday Baseball in Sabbatarian New England,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History & Culture (Fall 2005): 78-97.

- “Nichols Signs Baseball Bill.” Boston Herald, January 31, 1929, 3.

- “Graham McNamee.” Baseball Hall of Fame Ford C. Frick Award Winner, 2016. http://baseballhall.org/discover/awards/ford-c-frick/2016-candidates/mcnamee-graham

- Dr. Alfred Goldsmith. “Receiving Conditions Often Change in the Short Space of an Hour.” Springfield (MA) Republican, June 1, 1924: 49.

- Bob Coyne. “Hello Everybody.” Boston Post, June 20, 1931: 19.

- For example, “Fred Hoey Day at Wigwam Great Tribute to Radio Announcer.” Boston Globe, June 21, 1931: 25; and “Fans Turn Out to Pay Tribute to Fred Hoey at Wigwam Today.” Boston Herald, June 20, 1931: 5.