Can You Hear the Noise? The 1909 St. Paul Gophers

This article was written by Todd Peterson

This article was published in 2007 Baseball Research Journal

Like the 1987 world champion Minnesota Twins, the 1909 St. Paul Gophers featured a home-grown first baseman, a hard-nosed leader nicknamed “Rat,” and an outstanding center fielder from Chicago. Unlike the Twins, the Gophers were cruelly prevented from playing major league baseball because of the prevailing apartheid of the time. In the face of almost overwhelming racism, the club managed to win nearly 450 ball games during their five-year existence, while spreading the gospel of blackball throughout the upper Midwest. This is the story of that five-year period and the saga of their 1909 season, when the St. Paul Gophers became one of the greatest teams Minnesota has ever seen.

*****

The Gophers were formed in early 1907 by saloon owner Phil “Daddy” Reid, and his partner and childhood friend, John J. Hirschfield. A heavyset and confident-looking man, often pictured wearing a three-piece suit and a bowler hat, Reid was “one of the most influential and wealthy Negroes of the northwest,” renowned for being “of a cheerful disposition, always willing to do an act of kindness.”1

The pair enlisted Walter Ball, a product of the St. Paul sandlots and an outstanding blackball pitcher of the time, to organize and run the club. Ball drew most of the team’s original roster from Chicago, securing many players who had been released when Rube Foster took control of the Leland Giants. Ball himself rejoined the Giants in mid May, and the future for “both the managers and players, looked very shady” indeed. However, thanks to traveling secretary Irving Williams’ acumen in scheduling games and garnering publicity, and Reid’s “determination to succeed at all costs,” the Gophers were soon competing against the best town teams and semi-pro clubs in Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, and the Dakotas, winning a reported 92 games, with only 15 losses and 2 ties—a remarkable .853 percentage.2

Led by pitchers Clarence “Dude” Lytle, Johnny Davis, and slugging catcher Jesse Schaeffer, the Gophers won 36 straight games at one point and in mid-September defeated the St. Paul Saints of the American Association two games to one, with one tie, to capture the “colored championship of the state.” Reid imported his good friend Rube Foster from Chicago to pitch the deciding game and the burly Texan, looking “as big as a fully matured hippopotamus,” allowed only five hits and struck out 10 Saint batters as the Gophers prevailed, 5-3. The season also proved to be a success financially, and as the St. Paul Dispatch rhapsodized, “The Gophers have been a great advertisement to the city of St. Paul this season.”3

Before the beginning of the 1908 campaign, Reid jettisoned a few of the previous year’s aging veterans and added a trio of great players to the team, second baseman Felix Wallace, pitcher “Big” Bill Gatewood, and catcher George “Rat” Johnson. Although hampered by injuries that reduced the team to a two-man rotation of Lytle and Gatewood for much of the year, the Gophers won over 95 games against only 28 losses and a tie.

Rube Foster returned to the Twin Cities to help out the Gophers during the last week of August and threw a 5-0 no-hitter against the Hibbing Colts, a tough squad from Minnesota’s Iron Range, composed entirely of ex-professional players.4

In September, the team dropped a barnstorming series to the Saints, but the Gophers’ main focus that summer was a turf war with a new black ball club in the Twin Cities, the Minneapolis Keystones, run by flamboyant bar owner Edward ”Kidd” Mitchell. The Keystones were a more rambunctious lot than the Gophers, and they slugged, fought, and argued their way to a reported 88-19-2 record, led by second baseman Topeka Jack Johnson, slugging third baseman William Binga, and hometown hero Bobby Marshall at first. After much posturing and haggling, the two squads agreed to meet in a five-game showdown series for a $500 side bet, stretched over late August and September. The Keystones, behind their ace, Charles “Slick” Jackson, won two out of the three first contests, but the Gophers rebounded to take the last two games and the series, with Lytle besting Jackson 6-0 in the finale at Nicollet Park in Minneapolis.5

*****

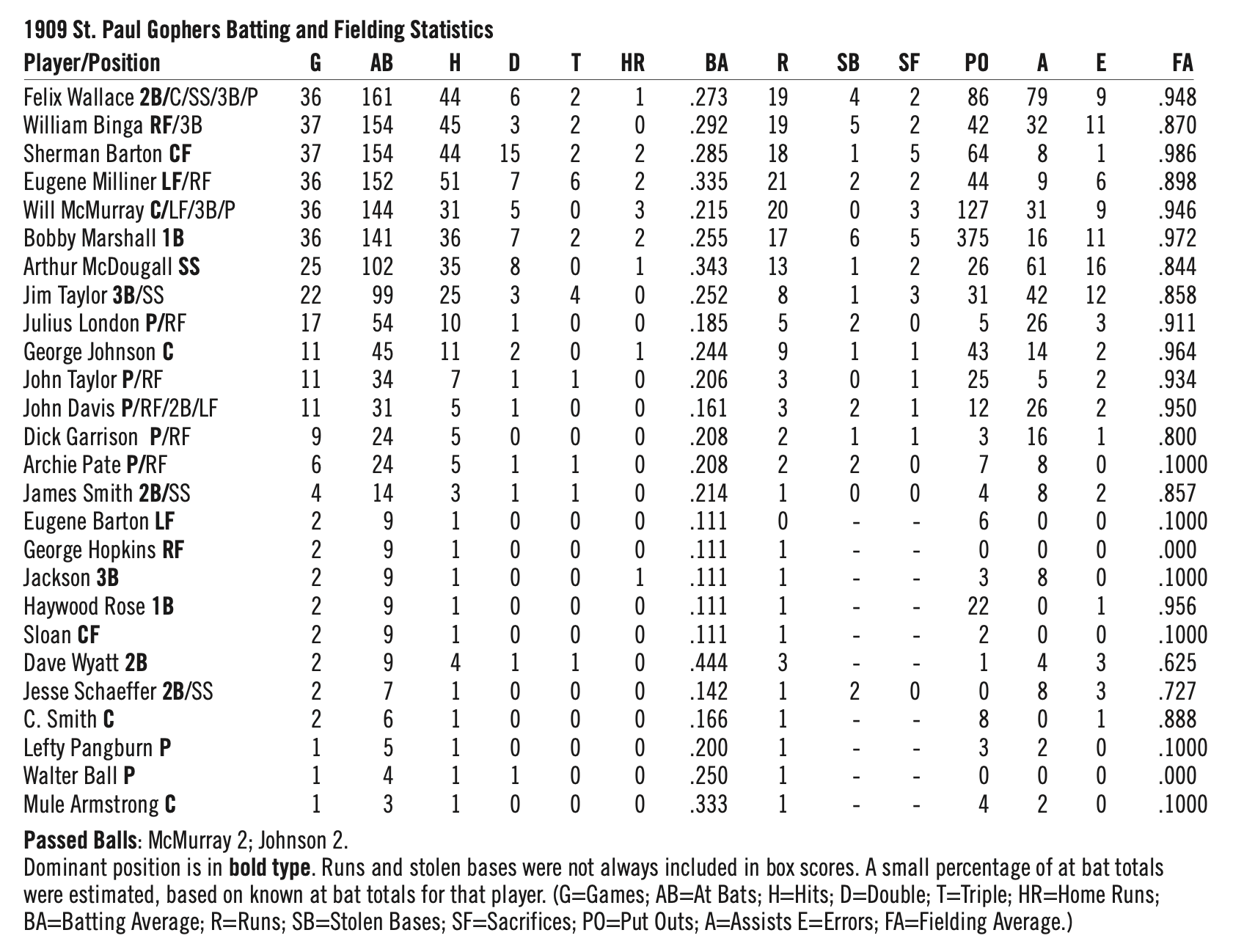

For the season of 1909, Reid and Williams were intent on fielding their best team yet, and before the season started Reid embarked with the Leland Giants on their spring training trip throughout the South, searching for players for his club. The Gophers, “composed of the fastest [“fast” meaning excellent in the parlance of the day] colored players in America,” returned four players from their 1908 roster.

The backstop was 13-year blackball vet George “Rat” (short for Rastus) Johnson, whom Hall of Fame Cubs manager Frank Chance once described as the greatest catcher in America. The 33-year-old native of Bellaire, Ohio, was a deadly clutch hitter and a heady receiver whose pegs down to second were “as regular as clockwork.” The “Rat,” or “Chappie” as he later became known, led the Renville All Stars to the Minnesota state championship in 1905 and spent several spring trainings around this time tutoring young pitchers for the St. Paul Saints and the Boston Nationals.6

Twenty-five-year-old Felix Wallace had no superior as a second baseman. The Gophers captain was a great hitter, crafty base runner, and “one of the brainiest and clever infielders ever produced in the Negro ranks.” Possessing tremendous range, Wallace would make most of his throws to first with a quick short-arm motion while standing in almost any position. Utility man William McMurray, a graduate of the St. Louis sandlots, was a versatile, hardworking player with an ability to lead. He was also a jovial sort, known for joshing with fans “and being ever ready with repartee.”7

Thirty-four-year-old Sherman Barton was a hard-hitting center fielder from Illinois with a cannon for an arm. The Indianapolis Freeman once noted, “When it comes to fielding and retiring runners, Bucky Barton of the St. Paul Gophers ranks with the big leaguers. They all fear him.”8 The new position players included diminutive yet sure-hitting shortstop Arthur McDougall, a former teammate of Wallace’s from the Paducah (Kentucky) Nationals, who possessed “an arm like a mule’s hind leg.” The incoming left fielder was Eugene “Gabbie” Milliner, perhaps the fastest man in all of baseball, renowned for his slicing line drives just inside the third base bag.9

The competition between the Gophers and Keystones had intensified during the off-season with quite a bit of player movement between the two teams. Left fielder Willis Jones, shortstop Frank Davis, and first baseman Haywood “Kissing Bug” Rose of the 1908 Gophers ventured east across the river to join the Mill City club, while the Keystone corner infielders, third baseman Bill Binga and first sacker Bobby Marshall, hooked up with Reid’s outfit.10

Binga, a seasoned vet of nearly 20 blackball campaigns, was truly a professional hitter and was racking up multiple-hit games well into his 40s. In the field he was limited in range, but he never forgot an opposing batter, or how and where he liked to hit. Although born in Milwaukee, Bobby Marshall grew up in the Twin Cities, and won seven letters for football, baseball, and track at the University of Minnesota from 1903 to 1907. His gridiron accomplishments were so spectacular that he was named to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1971. Marshall, who briefly tried out with the Gophers in 1907, before sticking with the Keystones in 1908, would spend the next 20 years playing professional baseball and football. He was a good base stealer, with some pop in his bat, and a long reach at first.

Vic Turosky, who played professional football against Marshall in Wisconsin, recalled a play where the 6-foot-1, 180-pounder, picked him up by an ankle, flung him into the air, and slammed him on his head. Turosky marveled, “That’s when I knew what real power was.”11

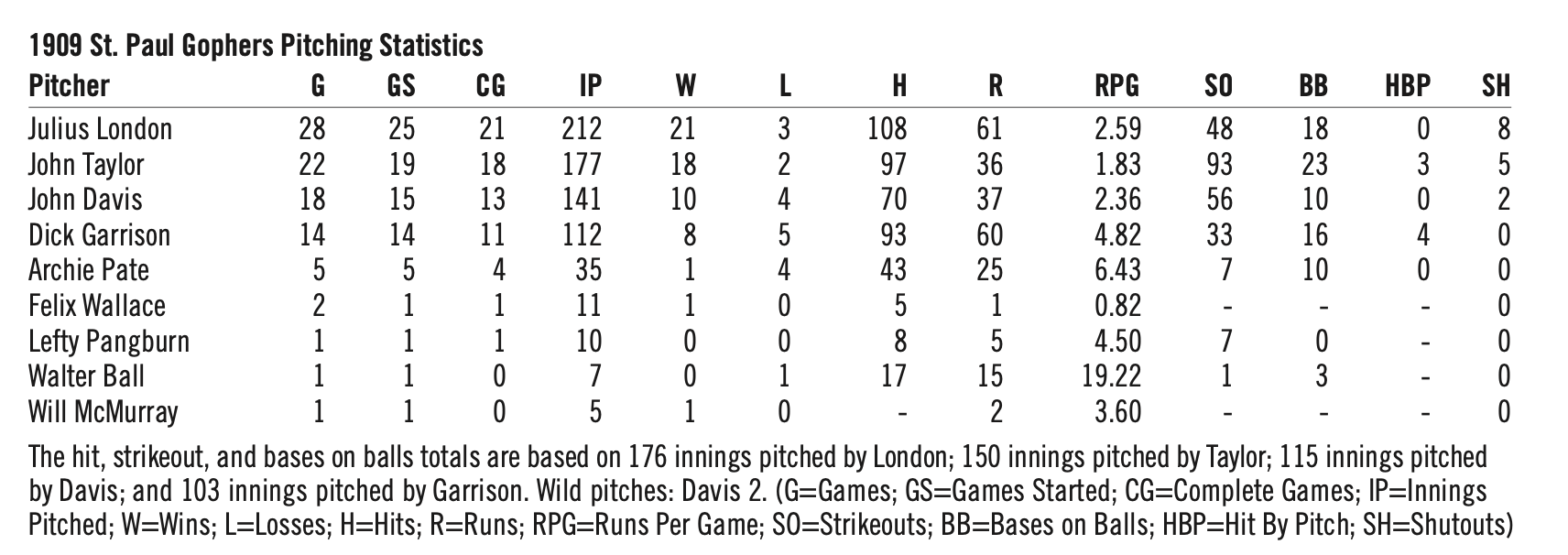

The all-new pitching staff consisted of Julius London, “the three fingered wonder,” formerly of the Texas League, Archie Pate; a young spit-baller out of Chicago; and Richard Garrison, who despite being only about five feet high, had “speed and curves to burn.” The Gophers had crisscrossed the Midwest in 1908, journeying over 5,000 miles by train, and they would repeat this trick in 1909. Due to some inconsistent pitching, the Gophers got off to a slow start, including a sweep at the hands of the Lacrosse team of the Wisconsin-Minnesota league to start the season. A Hibbing newspaper noted after the Gophers barely won an early season series from the Colts that “the Gophers are much weakened in the box this year.”12

The club suffered another setback in mid-May when Rat Johnson jumped the club to manage the Long Prairie team of central Minnesota. Things brightened considerably soon after with the arrival of a brother combination from Birmingham, Alabama, signed by Reid during his Southern excursion. Twenty-four-year-old Jim Taylor took over at third base while his older sibling Johnny inherited the struggling Pate’s turn in the rotation and won his first 14 decisions, sparking the club to a 30-7-1 mark during their five-week sojourn through the Dakotas, Wisconsin, and northern Minnesota.13

The second eldest of four legendary baseball-playing brothers, clean-living, hardworking, John Boyce Taylor was given the sobriquet “Steel Arm” in 1898 by a white reporter from the Charlotte Observer, who witnessed his blazing fastball mow down the Shaw University nine. Possessing a good assortment of curves to complement his heater, Taylor averaged between 30 and 40 starts a season during his six-year tenure with the Birmingham Giants, while losing fewer than 40 games in that span. During a 1908 game in San Antonio, with the bases loaded and nobody out in the bottom of the ninth, Steel Arm Johnny struck out the side to win a 1-0 duel against Cyclone Joe Williams.14

Jim Taylor carried a big bat, both literally and statistically, hitting no lower than .290, with a high of .340 in 1907, during five seasons with the Birmingham Giants. His fielding average at third base was “exceptionally high,” and on the base paths he was “inclined to create the impression of dogginess, but he is quicker than chain lightning in a pinch.”15

After a few rocky outings in June, Garrison was sent packing in favor of 28-year-old Kentuckian Johnny Davis, who had won over 25 games for the Gophers in 1907. The slightly built, bespectacled Davis was a “clever cross fire artist” known for possessing a “very tantalizing slow curve and fine control of a change of pace delivery.” While pitching for the Gophers in July 1907, Davis had no-hit La Crosse of the Wisconsin League, 2-0, and that fall while pitching for the Philadelphia Giants in Cuba, he won seven games while posting a 0.68 ERA.16

In late June it was announced that the Gophers and the Leland Giants would play a five-game series in St. Paul for “the world’s championship,” and that Daddy Reid “has already placed a large sized roll of coin on the outcome of the series.” During the previous three years the Lelands had crushed every team they had played, whether they be white, black, semipro, or from organized ball, including the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, who dropped four out of five games to the Giants in September 1908. The eventual champs of the Chicago City League boasted an outstanding pitching staff of former Gophers Walter Ball, Bill Gatewood, and southpaw Charles “Pat” Dougherty, who had been poached from the West Baden (IN) Sprudels when Foster broke his leg against the Cuban Stars in mid-July. Ball would post a record of 12-1 in the city league that year, and the trio would dominate blackball for most of the next decade.17

Hall of Fame center fielder Preston “Pete” Hill anchored the Leland’s powerful lineup by hitting .311, with 15 doubles and 21 runs scored in 37 city league games that summer. Lending Hill a hand was first baseman Harry “Mike” Moore, who roughed up city league pitching by hitting .341, and Charles “Joe” Green, who responded with a .316 average after regular left fielder Bobby Winston fractured his ankle.18

The Gophers were also playing shorthanded. On the day before the Leland series was to begin, Arthur McDougall, hitting well over .300 at the time, was struck by a pitch during an 8-4 victory over the Keystones, knocking him out of the lineup for the rest of the year. Jim Taylor replaced McDougall at short, Binga returned to third, McMurray moved out to right field, and “Rat” Johnson came back from Long Prairie to temporarily help the Gophers out behind the plate.19

The series, specially scheduled to coincide with the national Black Elks convention being held in St. Paul, was played at the Saintly city’s Downtown Park. The “pillbox,” as the stadium was commonly known, was a wooden structure confined to a small city block. A high fence, topped by a 20-foot wire screen, surrounded the place and the grandstand and bleachers were located less than seven yards from the field of play. The park had virtually no foul territory, and the outfield dimensions were so small, 280 feet down the left-field line, and no more than 210 feet to right, that foul pops and triples were almost unheard of. Right fielders played only a few feet behind the second baseman, with their backs against the fence. Balls hit over the right and left field fences were ground-rule doubles, and only pitches knocked over a limited area in center field were counted as home runs.20

“A thousand or more colored fans and a good sprinkling of white ones” crammed into the tiny ballpark on Monday afternoon July 26, to watch Julius London oppose Bill Gatewood in the lid lifter. The afternoon crowd was treated to a three-hour donnybrook featuring several shifts in momentum as the hometown club pounded out 22 hits while the Giants came up with 14 safeties of their own. Jim Taylor paced the Gopher attack with four singles and a double, and McMurray, Barton, and Binga chipped in with three hits apiece. For the Lelands, right fielder Andrew “Jap” Payne doubled once, singled twice, stole two bases, and scored three times, while shortstop George Wright smashed two doubles, and Joe Green added three more hits to the cause.21

The Gophers jumped out to a quick 1-0 lead in the first before the Giants exploded for four runs in the fourth and added single runs in the fifth, sixth, and seventh, driving London from the hill in favor of Johnny Taylor. The Gophers, in turn, knocked out Gatewood with a three-run fourth inning and two runs each in the sixth and seventh frames before Walter Ball came on to stop the bleeding.22

Trailing 8-7, the Lelands came up with the equalizer in the top of the ninth and pushed another run across in the 11th for a 9-8 lead. It looked like another famous Giant victory, especially when Eugene Milliner grounded out to second to start the Gopher half of the 11th. However, in lightning succession, Binga singled, Johnson doubled, and Bobby Marshall drove the first pitch Ball threw his way over the cigar sign just to the left of the center field home run pole and into the lots across the street. And the crowd, according to the St. Paul Pioneer Press, went wild:

Can you hear the noise? It was thick and heavy and was plentifully interspersed with cries of “Hel-lup! Hel-lup! Hel-lup!” not by the losers but by the winners to show how badly their vanquished foes felt about it.23

Both clubs adjusted their lineups before the start of the second game on Tuesday.

The 40-year-old Binga, not the most nimble of third basemen, switched places with McMurray in right, while the Lelands replaced catcher Pete Booker, who had gone hitless in the opener, with Sam Strothers, who collected two hits before giving way to Booker midway through the contest. In contrast to the opener, neither team scored a run during the first six innings as Johnny Davis and the Giants’ lefty Pat Dougherty dueled before a good-sized crowd of 1,500. Davis was aided by some fine glove work by Felix Wallace, who recorded six putouts and five assists without error, and by three assists by the Gopher outfield. Dougherty was more dominant, striking out nine batters during a performance that “was as fine an exhibition of twirling as is seen, even in the big leagues.”24

In the top of the seventh, Davis faltered and the Lelands scored three times, thanks in part to errors by Davis and Bobby Marshall. The Giants pushed their advantage with three more runs in the eighth and finished their 13-hit onslaught with two more runs in the ninth. Andrew Payne was once again the catalyst for the Lelands with three hits, including another double. After a relatively quiet game one, Pete Hill collected a single, double, and stole a base while scoring two runs. The Gophers broke up Dougherty’s shutout in the bottom of the ninth, when Jim Taylor scored on the back end of a double steal, but it was too little, and much too late to prevent the Giants’ 8-1 victory.25

The temperature prior to the start of the following afternoon’s game was a steamy eighty-five degrees, which didn’t prevent 800 fans from turning out to witness the matchup of Johnny Taylor and Walter Ball, the pitchers of record from game one. The home team staked Steel Arm Johnny to an early lead when Captain Wallace doubled to lead off the bottom of the first, stole third, and scored on Sherman Barton’s two out single. Ball settled down after that and allowed only three more hits while striking out five Gopher batters over the next seven innings.26

Taylor was even better through the first eight frames, protecting his 1-0 lead by scattering four hits and striking out six batters with his unorthodox delivery. According to the Pioneer Press, the 29-yearold native son of Anderson, South Carolina,

would throw arms and legs about in bewildering fashion, suddenly knot up like a porcupine, and then just as suddenly his left foot would dangle and shake in the air at the astounded batter as the ball flew past him.27

As usual, the Gophers provided great support behind him. In the fifth inning, Milliner made a running catch of a Leland fly ball up against the left-field fence and his momentum carried him into the boards “with a thud that was heard in the grandstand.” As the left fielder lay stunned, an “enthusiastic youngster” raced onto the field and relieved him with a glass of cold water. An inning later, Jim Taylor made a sensational backhanded grab of a line drive at short, picking it off “within a foot from the ground while going at full speed.”28

The intense heat got to Rat Johnson in the fifth inning, and he was carried from the field suffering from sunstroke. He was reportedly quite ill, but was able to continue. Meanwhile, the Lelands resorted to a bit of subterfuge in the top of the eighth, when Ball was pinch-hit for by Gatewood, but illegally returned to pitch the bottom of the inning anyway.29

In the ninth, Taylor’s toe and arm finally tired, and he gave up successive singles to Hill, second baseman Nate Harris, and Payne. The fatigued pitcher recovered to get Booker, but then third sacker Dangerfield Talbert singled, and Wright slammed a two-out homer. During the onslaught “Taylor just stood in the box and blinked his eyes as if he was waiting for the rain to blow over.” Five runs crossed the plate, although according to one Gopher, if Taylor had stuck to his “toe stunt” the Giants rally would never have happened. The Lelands sent Dougherty in to pitch the bottom of the ninth, and he struck out two more batters while preserving their 5-1 win.30

Down two games to one, the Gophers were forced to revamp their line up once again when Rat Johnson left to fulfill his commitment with the Long Prairie team. Ironically, Johnson would leave Long Prairie in early August to finish the season with Leland’s Giants. Once again McMurray replaced Johnson behind the plate while Wallace moved to shortstop and James Taylor shifted over to third. James Smith, a friend of Walter Ball’s and a captain of the Gophers during their inaugural season of 1907, was enlisted to play second for the remainder of the series.31

The starters for the crucial fourth game on Thursday were a repeat of the opener, with London opposing Gatewood. Umpiring the game, as he had throughout the series, was Andrew Thompson of St. Paul, who had a history with Big Bill. A year earlier Gatewood had nearly precipitated a race riot in the nearby river town of Stillwater when he hurled his glove into “Honest Andy’s” face while arguing balls and strikes. Hundreds of spectators angrily rushed the field, but Thompson, a number of civic leaders, and two policemen armed with clubs restored order, while the “big bully” Gatewood was hustled off the grounds.32

There is no evidence that Thompson held a grudge, but the Gophers got off to another good start against their former teammate, collecting their only three hits of the game in the first inning. After Wallace led off the bottom of the frame with a single to left field, Gatewood retired Jim Taylor, but then McMurray launched a double to deep center and one out later Milliner smoked a drive to the same spot for a 2-0 Gopher lead. The speedy left fielder stretched his hit into a rare Downtown Park triple, but Binga couldn’t bring him home. The home club scored two more in the third without the benefit of a base hit. Wallace and Taylor opened the inning by reaching on errors, and both later scored on a wild pitch. Trailing 4-0, Gatewood proceeded to knuckle down and he did not permit the Gophers another base runner.33

Pete Hill walked in the fourth inning and scored the Lelands’ first run of the game, propelled by a single by Nate Harris and a Gopher error. Hill drew another walk in the sixth and scored on a double by Harris that cut the Gopher lead in half, to 4-2. London pitched into the seventh, when it appeared “that the Lelands were finding him,” and Johnny Davis came on to finish the inning with no further damage done. The ever-dangerous Hill scored his third run of the game in the eighth, thanks to the third Gopher error of the afternoon, combined with another single by Harris and a fly ball by Payne.34

During the previous three games, the Giants had scored eight runs in the ninth inning, but Davis, looking to reverse the trend, got Talbert to fly out to start the final frame. Milliner couldn’t hang on to Moore’s long fly, however, and Jim Taylor mishandled Wright’s grounder, moving the tying run into scoring position and the go-ahead run at first with only one out. But Johnny Davis could pitch in the pinches. He struck out Joe Green before inducing Gatewood to ground out to Wallace at short, saving the 4-3 triumph, and pulling the Gophers even in the series.35

In the finale on Friday, the Lelands started Pat Dougherty, while for the local nine Steel Arm Johnny, true to his name, took to the mound on only one day’s rest. Although he was not as dominant as had been in the early going on Wednesday, Taylor kept the Giants at bay for most of the contest, no thanks to his support. In the third inning, the usually dependable Wallace booted Joe Green’s grounder, and Pete Hill doubled, which coupled with an error by Jim Taylor brought the first run of the game home. The Lelands added an insurance run in the eighth when Jap Payne singled, stole second, and scored on Moore’s clutch two-out single.36

The Gophers could do little with Dougherty, who while striking out seven during the first seven innings “had the local sluggers tied in all sorts of knots.” Wallace walked to lead off the fourth and James Smith coaxed a free pass in the sixth, but neither runner advanced past second. When Milliner came to bat to lead off the bottom of the eighth, the Gophers were two runs down and hadn’t hit safely in 14 innings, stretching all the way back to the first inning the day before.37 Years later Rube Foster would tell his players that they only needed to get one base hit during a ballgame, but that it had to come at the right time. Perhaps he was thinking back to what now occurred at the Downtown Park. Milliner lashed a Dougherty pitch into deep center and raced around the bases for another improbable triple. Binga was up next and the reliable one delivered a base hit that cut the Giant lead to 2-1. Marshall came up with a chance to repeat his game one heroics, and he managed to loft a fly to the outfield, but this time it stayed in the park, where it was caught for the first out of the inning.38

Johnny Davis, said to be able to “break up any game, at any time, with his big stick” pinch-hit for Smith and promptly singled, and both he and Binga moved into scoring position after some sloppy fielding by the Lelands. Walter Ball was brought in to face John Taylor, but Steel Arm Johnny, not a good stick, nevertheless “hit the ball for another bingle” and Binga and Davis both scored. Wallace and Jim Taylor both flew out to end the inning, but it didn’t matter. Incredibly, the Gophers had scored three runs off two of the best pitchers of the era, with the two crucial blows being struck by pitchers.39

The Giants in the ninth “tried every trick known to black or white players,” including switching runners, batting out of turn, and intimidating the umpire. Gatewood pinch-hit for Green, singled, and stole second, but Taylor retired Dougherty, batting illegally for Ball, Pete Hill, and Harris to wrap up the Gophers’ championship. The Gophers had hit safely in only two innings of the last two games of the series and managed to win both of them.40

Leland and Foster took the loss about as well as could be expected, claiming that the five games were only “exhibition contests.” Foster ungraciously wrote, “No man who ever saw the Gophers play would think of classing them world’s colored champions, or would think the playing ability of the other teams was very weak.” He went on to snipe that “no doubt they need the advertising.” The pair also complained that the absence of Winston and Foster greatly affected the outcome of the series. James Smith countered that the Lelands had won the city league with the same lineup that faced the Gophers, that when Smith filled in for Arthur McDougall he was out of practice and that

I fielded all right, but did not hit, which McDougall would have done; therefore the Gophers were the team that was weak, and deserve all the credit they can get for being game and having the staying qualities.41

It would also seem that the frequency with which the Giants relieved their starters and their shenanigans in the late stages of games three and five belie their claims that they considered the contests merely exhibitions. The Gophers had the last word on the subject when they shut the Lelands out, 2-0, on August 24 in the black coal mining community of Buxton, Iowa.42

Following the Leland series, a banged-up Gopher squad beat the Keystones, 8-3, to sweep the city series, as the remarkable Wallace filled in admirably at pitcher and catcher after starting the game at third. The club proceeded to drop two games to Jimmy Callahan’s Logan Squares of the Chicago League before huge crowds in Fennimore, Wisconsin, before Jesse Schaeffer, the star of the 1907 squad, returned to play second base and the squad proceeded to go 284 on a tour of Iowa and southern Minnesota. On September 26 Johnny Taylor won his 37th game of the season (28th with the Gophers) by beating a minor league all-star team, 5-2, giving the St. Paul nine a reported final tally of 88 wins out of 116 games played.43

All fall and winter the owners of other teams such as the Brooklyn Royal Giants and Kansas City Giants also made title claims in the country’s leading black newspaper, the Indianapolis Freeman, but the fact remained that the Gophers beat the Lelands before anyone else did, and that they posted a .846 winning percentage against other black squads that year. Unfortunately for Daddy Reid, the most persuasive argument for the Gophers’ preeminence came from Frank Leland himself when he signed Felix Wallace, Bobby Marshall, and the Taylor brothers away from the Gophers in November, prompting Reid to dissolve his club.44

In an odd twist, James Smith, perhaps with the knowledge that Reid was going to pack it in, led a pick-up Gopher squad, that included Walter Ball and a few Keystones, for a couple of games in Chicago that October, while Wallace and Marshall were in the Lelands lineup for their epic showdown with the Chicago Cubs. Marshall committed two errors and was pulled during the first game of the series, but Wallace collected three hits, including two off Three Fingered Brown as the Cubs took three hotly contested games from the Giants.45

*****

In the spring of 1910, leaders in the Twin City black community convinced Reid to reform the Gophers despite the defection of most of the 1909 club to other teams. Bobby Marshall and Jim Taylor rejoined the club in early June, and along with Indiana spitballer Louis “Dicta” Johnson, and a battery from Pittsburgh by way of the Buxton (IA) Wonders, “Lefty” Pangburn and catcher Mule Armstrong, the team went on to win a reported 104 games out of 131 tries.46

In late July, Frank Leland’s Chicago Giants led by Steel Arm Johnny Taylor and two other former Gophers, “Rat” Johnson and Felix Wallace, returned to St. Paul looking to avenge their 1909 defeat. The Gophers and Louis Johnson nipped Steel Arm Johnny and his mates, 4-3, in the series opener before a Lexington Park crowd of 4,000, when Jim Taylor stole second with one out in the 10th inning and scored the winning run off two subsequent Leland throwing errors. The Giants, behind the pitching of Taylor, Walter Ball, and a 24-year-old Cyclone Joe Williams, easily captured the next four games, however, and swept another three-game set from the Gophers in early September in Preston, Minnesota.47

During the Giant series in July, Phil Reid married famed actress and singer Belle Davis, and left for a honeymoon in Europe, leaving the club in the hands of road secretary Irving Williams. The squad slumped badly after Reid’s departure, and most of the club, save for Johnny Davis and Bobby Marshall, jumped the financially sinking ship in mid-September. The team rebounded in early October, aided by the return of Eugene Milliner and a few Keystones including Hurley McNair, to finish the season on a high note by beating the scrappy semi-pro North St. Paul Thoens, 3-1, thanks to a 10-inning no-hit effort by Charles Jackson.48

The following spring, Bobby Marshall, with the financial backing of tavern owner Grover Shull and Saints magnate George Lennon, reorganized the team as the Twin City Gophers. Marshall’s squad, a mixture of well-traveled vets such as Binga, Johnny Davis, and center fielder/pitcher Bert Jones and promising youngsters such as Dicta Johnson and shortstop William Selden, won about as much as they lost, mostly while barnstorming through the Dakotas.49

Dude Lytle, Pangburn, and Armstrong gave the club a little boost when they rejoined the team in late June, and the Gophers managed to beat the fading Leland Giants in Chicago, but the season was pretty much a disaster on the field and at the gate. Bobby Marshall either quit or was forced out in early August, and the team, called the St. Paul Gophers once again, left Minnesota later that month for a series in Kansas City and St. Louis before calling it a day.50

The 1911 season also proved to be the last campaign for Kidd Mitchell’s Keystones, who had spent most of their final two years of existence playing south of Minnesota, including a stint in the 1910 Texas Negro League, representing San Antonio. In the end, the decline of the Gophers’ and Keystones’ play, combined with the high cost of travel and the lack of a substantial black fan base in the Twin Cities, led to their demise. Over the next 35 years there were a few half-baked attempts to revive the Gophers or to trade on their good name, but when Daddy Reid died in St. Paul of heart failure in October 1912, big-time black baseball in Minnesota was laid to rest with him.51

In October 1987 the Minnesota Twins, behind locally born and raised slugger Kent Hrbek, third baseman Gary “The Rat” Gaetti, and Hall of Fame center fielder Kirby Puckett would also win a championship before a raucous home field crowd. Over 75 years earlier, however, the St. Paul Gophers had brought it home first.

Notes

- St. Paul Appeal, June 3, 1916; Twin City Star, October 26, 1912; St. Paul City Directory 1901, R.L. Polk, St. Paul, MN: Indianapolis Freeman, April 16, 1910.

- Minneapolis Tribune, September 26, 1907, February 2, 1908; St. Paul Appeal, August 31, 1907.

- St. Paul Dispatch, August 10, 1907; St. Paul Appeal, August 31, 1907. St. Paul Pioneer Press, September 24, 1907; St. Paul Daily News, September 24, 1907; Minneapolis Tribune, September 26, 1907.

- Minneapolis Tribune, August 30, September 13, 1908; St. Paul Pioneer Press, August 29, 1908.

- Minneapolis Tribune, April 3, 26, July 26, August 2, September 20, 21, October 4, 5,1908; St. Paul Pioneer Press, August 28, 31, September 16, 17, 20, 22, 23, 1908.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, April 5, 1909; St. Paul Dispatch, May 3, 1907; Long Prairie Leader, September 7, 1911.

- Frank Leland, Frank Leland’s Chicago Giants Base Ball Club, (Chicago: Fraternal Printing, 1910), 16; Indianapolis Freeman, April 16, 1910; St. Paul Dispatch, May 30, 1908; Bemidji Daily Pioneer, June 28, 1909; New York Age, July 13, 1911.

- 1880 United States Census, McLean County, IL; Twin City Star, July 21, 1910; Indianapolis Freeman, July 30, 1910.

- Chicago Tribune, August, 24, October 1, 1905; Twin City Star, July 21, 1910; Indianapolis Freeman, August 6, 20, 1910; Young America Eagle, October 1, 1909.

- Minneapolis Tribune, April 4, May 2, 1909; St. Paul Dispatch, May 15, 1909.

- Minneapolis Tribune, July 29, 1913; Twin City Star, July 21, 1910; Steven R. Hoffbeck, ed. “Bobby Marshall, the Legendary First Baseman,” Swinging for the Fences, Steven R. Hoffbeck, ed. (St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005), 60-61; Richard Rainbolt, Gold Glory, (Wayzata, MN: Ralph Turtinen, 1972), 35-36; Leland, 17; St. Paul Pioneer Press, May 20, 1907; Denis J. Gullickson and Carl Hanson, Before They Were Packers, Blue Earth, WI: Trails Books, 2004), 165.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, May 27, 1909; St. Paul Dispatch, May 15, 1909; Sawyer County Herald (Ashland, WI), July 15, 1909; Minneapolis Tribune, August 30, 1908; La Crosse Daily Chronicle, May 11, 1909; Hibbing Tribune Daily, May 25, 1909.

- Long Prairie Leader, May 11, 1909; St. Paul Pioneer Press, June 9, July 17, 1909; Leland, 13; Minneapolis Tribune, July 18, 1909.

- Leland, 14-15; James Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2002), 768.

- Leland, 13; Minot Daily Reporter, June 21, 1910.

- 1910 United States Census, Ramsey County, MN; St. Paul Dispatch, June 6, 7, 1907; La Crosse Daily Chronicle, July 3, 1907; Gary Ashwill, “Philadelphia Giants in Cuba, 1907,” http://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2006/07/index.html, June 10. 2006.

- St. Paul Appeal, June 19, 1909; St. Paul Daily News, July 25, 1909; Minneapolis Tribune, September 26, 1908; Chicago Tribune, July 13, 26, 1909; Riley, 48.

- Ashwill, “Mike Moore,” http://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2006/07/index.html, June 6, 2006; Chicago Defender, September 15, 1917; Leland, 9, 17-18, 20.

- Minneapolis Tribune, July 26, 1909; Indianapolis Freeman, December 11, 1909; Long Prairie Leader, July 30, 1909.

- St. Paul Appeal, June 19, 1909; Before the Dome: Baseball In Minnesota When the Grass Was Real, David Anderson, ed. (MN: Nodin Press, 1993), 23; Larry Millett, Lost Twin Cities, (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1992), 220-221; Stew Thornley, Baseball in Minnesota: The Definitive History, (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2006), 36.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 27, 1909.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 27, 1909.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 27, 1909; Minneapolis Tribune, July 27, 1909.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 27, 28, 1909.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 28, 1909.

- St. Paul Daily News, July 29, 1909; St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 29, 1909.

- Leland, 14; St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 29, 1909.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 29, 1909.

- Long Prairie Leader, July 30, 1909; St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 29, 1909.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 29, 1909.

- Long Prairie Leader, July 30, August 10, 1909; Indianapolis Freeman, December 11, 1909.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 30, 1909; Stillwater Daily Gazette, August 24, 1909.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 30, 1909.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 31, 1909.

- Ibid.

- Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (New York; Oxford Univ. Press, 1992), 111; Paul Pioneer Press, July 31, 1909.

- Twin City Star, July 21, 1910; St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 31, 1909.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 31, 1909.

- Indianapolis Freeman, September 25, November 13, December 11, 1909.

- St. Paul Appeal, September 18, 1909.

- Indianapolis Freeman, August 14, 1909; Fennimore Times, August 18, 1909; St. Paul Pioneer Press, September 15, 27, 1909; Leland, 15.

- Indianapolis Freeman, October 2, 9, 16, November, 20, 1909.

- Chicago Tribune, October 4, 11, 19, 22, 23, 1909.

- St. Paul Pioneer Press, April 10, October 3, 1910; Twin City Star, July 14, 1910; John Holway, Blackball Stars (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1992), 302.

- Twin City Star, July 21, 1910; St. Paul Pioneer Press, July 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 1910; Preston Times, September 21, 1910.

- Twin City Star, June 2, 1910, October 26, 1912; St. Paul Pioneer Press, October 3, 1910.

- Chicago Defender, April 15, 1911; Minneapolis Tribune, July 2, 1911.

- Chicago Defender, August 5, 1911; Twin City Star, August 19, 1911; Kansas City Journal, August 18, 28, 29, 30, September 1, 2, 1911; St. Louis Republic, September 4, 5, 1911.

- Indianapolis Freeman, June 18, 1910; Twin City Star, April 20, October 19, 26, 1912.