Canada’s First Professional Baseball League

This article was written by Martin Lacoste

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

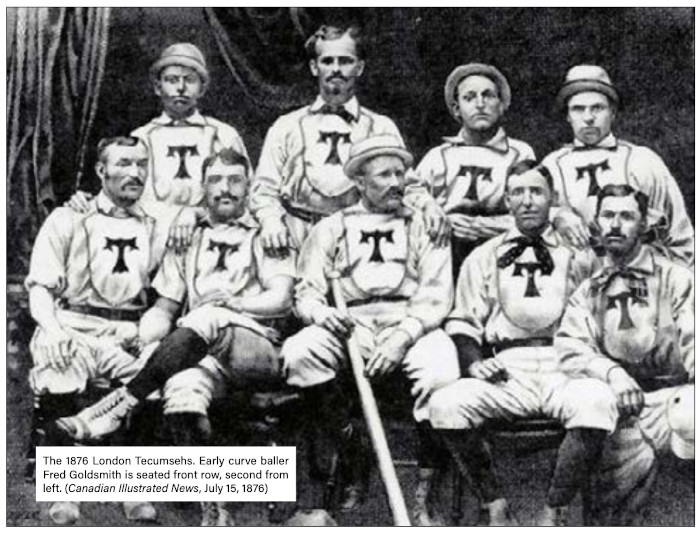

The 1876 London Tecumsehs. Early curve bailer Fred Goldsmith is seated front row, second from left. (Canadian Illustrated News, July 15, 1876)

1876: A seminal year in baseball. Club owners and organizers recognized the necessity of providing increased stability and an opportunity to elevate the game of baseball on a national level by establishing a new professional baseball league. While meetings held early in the year in Louisville and New York laid the ground for the inception of the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, similar meetings were held north of the border, in Toronto and Guelph, Ontario. These latter meetings resulted in the formation of the Canadian Association, the first professional league organized in Canada.

Organized baseball in Canada began in the 1850s, with the formation of teams in Hamilton (1854) and London (1855).1 The first game on record played under Canadian rules took place on September 15, 1856, between the London and Delaware clubs from London, Ontario. Two innings were played before the London club was declared the winner by a score of 34-33.2 Three years later, the first known game played under the New York rules3 took place on May 24, 1859, between the Hamilton Young Americans and Toronto Young Canadians. Toronto bested Hamilton by a score of 68-41.

Baseball expanded throughout southwestern Ontario in the 1860s, as nines were organized in Burlington, West Flamboro, Ingersoll, Dundas, and Guelph. These clubs remained amateur and independent, as team managers and secretaries coordinated games by telegraph and by post, and teams traveled by train for spirited contests and entertaining postgame events. As competitiveness increased and with it a desire for baseball supremacy, it was the Young Canadian Club of Woodstock, Ontario, formed in 1860, which staked a claim as the best club in Canada during these early years.4

As baseball’s popularity continued to grow, more teams emerged, and meetings were held in August 1864 in an attempt to establish an organized association of clubs from across Ontario.5 Though this did not come to fruition, it continued instead to be more customary for a Canadian champion to be crowned, earning the coveted Silver Ball trophy, after a short series of matches between the top contenders. Woodstock’s reign as champion lasted until 1869, when the Guelph Maple Leafs defeated the London Tecumsehs 43-20 in the championship match on September 24. In so doing, Guelph succeeded Woodstock as the new baseball dynasty in Ontario, as they kept possession of the Silver Ball as Canadian champions through 1875.

Baseball continued to expand in Ontario in the 1870s, resulting in larger crowds and increased coverage in the press. Teams from London, Guelph, Kingston, and Toronto scheduled more games in 1875, and team owners sensed the timing was right to proceed with another attempt at forming an organized association. On April 7, 1876, “a convention of Base Ball players was held at the Walker House, Toronto, for the purpose of forming an Association of the players of this game throughout the Dominion. There was a fair attendance, every leading club in Ontario being represented, with one noteworthy exception – the St. Lawrence, of Kingston.”6 Delegates from Guelph, London, Toronto, Dundas, and Dunnville were present, and the convention proved a success, as an “Association was formed as the Canadian Association of Base Ball players, and it was resolved that the entrance fee from each club contesting for the championship should be $10. The following officers were elected: – President, Geo. Sleeman, Guelph; Vice-President, Spaulding, Dunnville; Secretary, H. Gorman, London; Treasurer, W.F. Mountain, Toronto.”7

As clubs deliberated whether or not to join the Association, many teams continued to organize practice or exhibition games throughout the month of May. Team managers signed players and assembled their rosters, searching for key acquisitions that would ensure their club’s success. Several of these players had had prior major-league experience in the National Association, the precursor to the National League, while others attracted attention from major-league clubs during the season and in the years to follow.

The most notable player of the Canadian Association was undoubtedly the star pitcher for London, Fred Goldsmith. Before he joined the Tecumsehs, Goldsmith “played semipro and amateur ball in and around New Haven for several years, making a name for himself with his curveball. By 1875 he had drawn the attention of top-level professional teams, including the New Haven Elm Cities of the National Association.”8 The 19-year-old played one game at second base for New Haven on October 23, and achieved two hits and drove in a run in his debut. The Tecumsehs enticed Goldsmith north with an offer of $300 for 1876, and he proved himself worth every penny, as he led the team in batting and pitched every game for London, throwing at least nine shutouts in the process (in league and nonleague games). He remained with the club through 1878, then in 1879 played with Springfield of the National Association. Again, the major leagues sought him out, and he joined the National League Troy Trojans late in 1879, this time primarily as a pitcher. His brief sojourn with the Trojans drew the attention of Al Spalding and Cap Anson, secretary and manager respectively of the National League Chicago White Stockings, and they rushed to sign Goldsmith for the 1880 campaign. He starred with the White Stockings, winning 20 games each of the next four seasons. After a short stint with the Baltimore Orioles late in 1884, Goldsmith returned to London for the 1885 Canadian Association season, his last stint as a professional.

The Tecumsehs featured several other celebrated players, among them Goldsmith’s batterymate in London from 1876-78, Phil “Grandmother” Powers. Originally from New York, Powers debuted in the major leagues late in 1878 with the Chicago White Stockings. He played with four other major-league clubs from 1880 to 1885, chiefly with the Cincinnati Red Stockings. London also possessed an all-star infield, most notably shortstop Joe Hornung from Carthage, New York, who spent 12 seasons in the major leagues from 1879 to 1890 with four clubs, primarily with the Boston Beaneaters.

The major-league career of third baseman Mike Led-with, from Brooklyn, was significantly shorter, as he had played a single game with the Brooklyn Atlantics in 1874. First baseman George “Jumbo” Latham, from Utica, New York, had played in the National Association in 1875 with Boston and New Haven before he joined the Tecumsehs in 1876. Latham played with the National League’s Louisville Grays in 1877, then returned to play in the majors from 1882 to 1884 with the American Association’s Philadelphia Athletics and Louisville Eclipse. Two of London’s outfielders also played in the major leagues. William Hunter, from St. Thomas, Ontario, played with Guelph, St. Thomas, and Saginaw, primarily as a catcher, before briefly joining Jumbo Latham for two games with the Louisville Eclipse in 1884. And Jack Leary, from New Haven, Connecticut, the consummate utility player, played at every position except catcher with seven different major-league teams between 1880 and 1884.

The Guelph Maple Leafs, in a bid to rival the Tecumsehs, coaxed several prominent players to join their roster, including third baseman Michael Brannock, from Massachusetts, and shortstop George Keerl, from Baltimore, each of whom had played briefly with the Chicago White Stockings in 1875. Infielder Harrison Spence, from New York, never played in the major leagues, but managed the Indianapolis Hoosiers to a seventh-place finish in the National League in 1888. Perhaps the most notable player to join the Leafs, however briefly, was Pete Hotaling, from Mohawk, New York. After several previous efforts had been made to sign Hotaling, the outfielder finally left the Ilion club in midseason and debuted in right field for Guelph on August 9, only to return to Ilion a few days later. Hotaling saw regular playing time as a major-league outfielder for six teams in the National League and American Association between 1879 and 1888, concluding his major-league career with a respectable .267 batting average.

The only other Canadian Association player to play in the major leagues was Dundas native Charles “Chub” Collins, who played a handful of games at second base for Hamilton in 1876 as an 18-year-old, then several years later played for the National League’s Buffalo Bisons and Detroit Wolverines, and the American Association’s Indianapolis Hoosiers, in 1884 and 1885.

With the players then in place, the first “Base Ball Match for the championship, between the Maple Leafs of Guelph and the Tecumsehs of London”9 was touted as one of the most important events of “the fifty-seventh anniversary of the birth of Her Most Gracious Majesty Queen Victoria”10 on May 24, 1876. Admission to the Exhibition Grounds in London was set at 25 cents a couple for seats nearest the entrance gates, and “for the balance of the seats ten cents will be the rate.”11 Ladies and club members were admitted free, and the Great Western Railway made special arrangements for visitors from Guelph, offering round-trip tickets for $2.12

After an estimated 6,000 spectators, nearly half of whom were ladies, “had been treated to the usual opening ceremonies of the ball game – such as throwing, striking and catching – the appearance of the Maple Leaf nine at the entrance gate of the grounds was greeted with cheers and welcomes from thousands of tongues.”13 The toss was won by the Maple Leafs, and the Tecumsehs went to bat first, with Mr. William McPherson, second baseman for the Toronto club, acting as umpire.

London took an early lead with four runs in the second inning, courtesy of timely hitting by the Tecumsehs and errors by Guelph players Hewer, Maddock, and Myers. London expanded its lead in the fifth inning, scoring three more to run the score to 7-2 in its favor. But Guelph would inch back with two in the bottom of the inning, then one each in the seventh and eighth innings to close the gap to 7-6. In the bottom of the ninth, Guelph pitcher William Smith “made a clean hit for two bases and got third on Dinnen’s misplay.”14

A wild pitch by London pitcher Fred Goldsmith brought in Smith for the tying run and forced the game into the 10th inning. In the top of that inning, London shortstop Dutch Hornung “planted a safe [hit] to right centre, reached second and third on passed balls and remained there unable to touch the goal,”15 while Thomas Gillean and Thomas Brown were retired, the latter by a timely strikeout, the only one of the game by Smith. But with two outs, catcher Phil Powers drove a ball to center field that Lapham could not reach, plating Hornung for an 8-7 lead.

In the bottom of the 10th, Guelph was put out by two groundouts and a foul tip by Emery “into Powers’ unerring hands and the victory was won.”16 “Thus ended one of the best contested and most exciting games of base ball ever played in Canada.”17

In the evening “the players of both teams, with the officers of the Tecumsehs, enjoyed a pleasant social time at the Tecumseh House.”18 The organizers of the league could not have imagined a more thrilling beginning to their venture, one they hoped would kindle fervent enthusiasm for baseball among the citizens of the urban centers of southwestern Ontario.

With the Canadian Association season now officially underway, four clubs had by this point submitted the requisite entrance fee: The Maple Leaf Club of Guelph, Tecumsehs of London, Standards of Hamilton, and the St. Lawrence Club of Kingston. The final club to join, the Clippers Club of Toronto, entered into the competition for the Canadian championship in late May, despite not having a ground on which to practice, nor even a “representative nine.”19

Eventually these were both secured, and it was these five clubs that comprised the Canadian Association for 1876. Over the succeeding four months, they sought to ascertain whether Guelph could retain its Canadian championship or a new Canadian champion would be crowned.

The next league game, played on June 10, was a decidedly one-sided affair, with the London Tecumsehs defeating the Hamilton Standards in their first league game by a lopsided score of 27-1. The Toronto Clippers, often also nicknamed the Torontos, launched their season opener on June 17 against Hamilton. Though their belated entry into the league caused many to speculate that the Clippers would provide little competition, they nevertheless upset the Standards by a score of 5-3 for their first win.

Holiday celebrations in the nineteenth century often showcased a game of “base ball” as the centerpiece for the day’s events. Dominion Day festivities in Kingston on July 1 were highlighted by the debut of the St. Lawrence club, in a league match with the Hamilton Standards. The St. Lawrence club, “the majority of whom display an unusual amount of flesh and muscle,”20 were at a severe disadvantage with “the recent desertion of a couple of men occupying important posts.”21 And, “as ill luck would have it, the catcher did not arrive and the pitcher, Curtain, did not arrive in consequence of illness.”22

Hamilton, for its part, was more than a little apprehensive, admitting that “they represent amateur talent only.”23 Throughout the game their “weakness [was] apparent, especially in the batting and fielding,”24 and it was perhaps merciful that rain curtailed the game after five innings. Those in attendance who braved the elements were rewarded with an 8-3 victory by the home team. Supporters were hopeful the win would give “hope of Kingston cutting a good figure in impending matches,”25 but as the season progressed, this proved overly optimistic.

The long-awaited return match between London and Guelph took place in Guelph on July 20, with another sizable crowd of 5,000 in attendance. They were treated to another evenly-matched battle, but five runs in the fifth inning by the Tecumsehs and solid pitching by Fred Goldsmith secured another victory for London, 10-7. As it became evident that London and Guelph were the top contenders for the championship, the rivalry between them heightened, and this was both chronicled in and fueled by the press. It was, for instance, reported that the London citizens were more than enamored by the supremacy shown by their club: “It is rumored they intend having the statues of their nine cast in bronze and placed to ornament some of the principal public buildings, such as the Court House, the Lunatic Asylum, etc.”26

The third contest between the Tecumsehs and Leafs took place on the Civic Holiday, August 9, and was highlighted by another dominant performance by Goldsmith. He allowed only four singles as the Tecumsehs applied “what an on-looker called ‘an everlasting coat of whitewash’ to the Maple Leafs – something never before done,”27 to a final score of 5-0. The Leafs did not recognize the loss, as Guelph President George Sleeman “handed to the Judiciary Committee of the Canadian Base Ball Association a protest against the game … on the ground of erroneous and partial decisions by the umpire.”28

Committee chairman Edwin M. Moore of London was “chosen at the request of the Guelph men [to provide a ruling], who knew him well, and they certainly should be the last to growl at any of his decisions,”29 at least according to the London Advertiser. The Guelph Mercury unsurprisingly and unequivocally opposed this assertion, warning “all clubs against allowing him to act in such a position.”30 The committee, in what would prove to be a crucial ruling come season’s end, sided in Sleeman’s favor, and the game was eventually “struck out of the championship record for violation of rules.”31

In between league contests, Canadian Association clubs engaged in exhibition games, typically with other Ontario teams such as the London Atlantics, Guelph Silver Creeks, Woodstock Excelsiors, Cobourg Blue Stockings, and Stratford Maple Leafs. They also accepted challenges from American clubs, including several from New York (Ilion, Utica, Ogdensburg, Ithaca, etc.) as well as with nines from Detroit, Jackson, Indianapolis, and Fort Wayne, Indiana.

The most notable exhibition games of the season occurred during the Canadian tour in late August by the National League’s St. Louis Browns. The Browns, second in the League race at the time with a record of 35-17,32 were nevertheless defeated by both London and Guelph in two thrilling contests on August 28 and 29 (10-9 in 10 innings, and 9-8 respectively). The following day, the National League-leading Chicago White Stockings, with a record of 42-12,33 ventured to London as part of their tour to battle the Tecumsehs. “An immense number of persons were on the ground, probably over 3,000,”34 and though London fandom was proud of its club’s recent successes, there was not much hope held for victory: “The current opinion yesterday was that Chicago would win the game of base ball with the Tecumsehs by a score of about 12 to 3.”35

The White Stockings lineup featured legends Ross Barnes, Cap Anson, Cal McVey, Deacon White and pitcher-manager Al Spalding, and though Goldsmith held them scoreless for the first two innings, Chicago eventually collected 16 hits and almost “Chicagoed” the Tecumsehs, a single run in the bottom of the ninth making the final score 10-1.

By September, three Canadian Association clubs were decidedly out of contention for the championship. Kingston’s league matches were all played at home, in eastern Ontario, evidence that the team presumably lacked the means to support extended travel to southwestern Ontario. This placed the burden on other clubs to travel a significant distance for any engagement, and the St. Lawrence club accordingly secured only a handful of matches.

Guelph was able to head east in late September to complete its matches against Kingston, and in two days the Maple Leafs easily took four games from Kingston, outscoring them 52-12 overall. Despite its promising debut on Dominion Day, Kingston finished the season 1-6. The Hamilton Standards and Toronto Clippers both concluded their dismal seasons with humiliating whitewashings (Hamilton lost to Toronto 15-0 on September 9, and Guelph defeated Toronto 33-0 on September 16), and joined Kingston at the bottom of the standings. (Hamilton finished 2-7; Toronto finished 2-9.)

It remained for Guelph and London to contend for the Canadian championship. The Guelph Maple Leafs concluded their season with a splendid 14-4 record, but as the four losses all came at the hands of the London Tecumsehs, it was apparent to most knowledgeable observers which team had secured the Canadian championship. However, the decision regarding the game from August 9 meant that the “official count stood in favor of the Tecumsehs by 3 games won and 0 lost,”36 which was in violation of Article XIII, Section 3 of the Championship Code, which stated that “the series for the championship shall be four games, and each club shall play four games with every other contesting club.”37

As a result, “the Judiciary Committee of the Canadian Association met in Hamilton on October 22 and heard protests from the Maple Leaf Club against awarding the Championship to the Tecumsehs.”38 “Considerable discussion took place as to whether the protest should be sustained or not,”39 and the majority of the Committee held that the remaining game was “not necessary to make their record valid.”40 The Committee therefore “declared the Tecumseh Base Ball Club, of London, champions of Canada for 1876, which entitles them to fly the championship pennant during 1877.”41

Also bestowed upon the Tecumsehs was “the Silver Ball offered by Mr. Wm. Bryce,”42 awarded to “the club winning the greatest number of games in Canada during the season of 1876.”43 This offer was intended to “encourage the game of Base Ball among Canadian clubs,”44 and was even sanctioned by the Canadian government when it was “entered according to act of Parliament … in the office of the Minister of Agriculture at Ottawa.”45

Who was this “Mr. Wm. Bryce”? William Bryce was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1846, to William Bryce, gardener, and Catherine Berry Speirs. The family emigrated to Canada in 1854, first to Toronto, then to London, where William Jr. set up a bookstore on Richmond Street in the early 1870s. He expanded the business to include the sale of stationery, “music, music books, fancy books, wrapping papers, twines, small wares, and all kinds of games.”46 His interest in games and sports further intertwined with his business interests when he became a shareholder in the Tecumsehs.47

Then in April 1876, he published the Canadian Base Ball Guide for 1876, the “only book published that [contained] the Constitution, By-Laws and Rules of the Canadian Association of Base Ball Players.”48 For the price of 10 cents, readers could also consult a history of baseball in Canada, as well as statistics and club records from 1875 for Guelph and London. The guide served not only to publicize the Canadian Association, but also to promote Bryce’s business, as full-page ads were also featured for Bryce’s Ontario Game Emporium on Richmond Street, an outlet in which one could purchase fishing tackle, boxing gloves, and, predictably, baseball equipment, including balls, bats, and uniforms.

What inspired Bryce’s enthusiasm for baseball is not evident, but of interest is that in 1871 he lived next door to Margaret Morrison,49 whose 12-year-old son, Jonathan, later played for the Guelph Maple Leafs and Toronto Canucks, and also served two stints in the American Association in 1884 and 1887. Whether Bryce and Morrison had a more tangible baseball connection is not known, and though this is perhaps mere coincidence, it is at minimum a reflection of the widespread popularity of baseball in urban centers in southwestern Ontario during the 1870s.

Bryce continued to advocate for baseball in Canada with the publication of the Canadian Base Ball Guide for 1877. It followed a similar format to the previous edition, but printed instead the constitution and playing rules of the International Association for 1877. The guide also contained partial team statistics for Guelph, London, and Toronto from the year before, and A.G. Spalding granted permission to publish the National League team rosters for 1877.

Bryce’s association with baseball appears to have ceased after the publication of this second volume. He moved his business to Toronto in 1886, but “was burned out in the great Toronto fire [of 1904], and [from then on] carried on business at King and Spadina.”50 He died in 1921, eulogized as “one of the oldest wholesale booksellers and stationers in Canada,”51 having published a variety of magazines, games, maps, and books.

As mentioned, the primary focus of Bryce’s 1877 guide was on the coming inaugural season of the International Association. It made no reference to a sophomore campaign for the Canadian Association, as by the time the guide was published, it was evident that no such campaign would take place. On the heels of their success in 1876, the Tecumsehs were keen on seeking out other top opponents, and “an unexpected opportunity arose in late 1876 when [London manager] Harry Gorman learned some American clubs were considering a new organization of professional clubs to rival the National League.”52

Gorman attended the International Base Ball Convention in Pittsburgh in February 1877 on behalf of the Tecumsehs, and “presented credentials from the Maple Leafs … and was admitted to the Convention as [their] representative”53 as well. “An organization was effected under the title of the International Association of Base Ball Players,”54 with Gorman elected as vice president, and George Sleeman, Guelph manager, elected to the Judiciary Committee.55

At first, this development did not hinder plans to continue the Canadian Association for a second season. A “second annual convention of the Canadian Association of Base-ball players”56 was held in Toronto on April 5, 1877, with representatives “from the Maple Leaf (professional), the Maple Leaf (amateur), and the Silver Creek, all of Guelph; the Athletic, of London; the Iroquois, of Markham; the Athletics, of Elora; and the Torontos, of Toronto; various other clubs in the Association being represented by proxy.”57

It was not a fait accompli that London and Guelph’s admittance to the International Association would naturally preclude their participation in the Canadian Association, though “it was a noticeable fact that the Tecumseh Club, of London, did not think it worth while to send a representative.”58 This observation did cause some speculation and doubt as to the future of the Canadian Association: “Were the Tecumseh Managers of the opinion that by absenting themselves they would break up the association and thus hold the championship pennant for the season of 1877 without earning it? If such was the case, they were mistaken, as the Association is now on a sounder basis than ever.”59

This optimism was shared by the Guelph Maple Leafs and their owner, George Sleeman, as he was reelected president of the league for the coming season. However, by May 23, five clubs had entered the amateur championship of Canada, but “the only entry for the Professional championship of Canada [was] the Maple Leaf, of Guelph.”60 By then, both the Tecumsehs and the Leafs had commenced play in the International Association (headlined by an exciting 2-1 victory by London over Guelph on May 17 to launch the latter’s season), and all hopes for the return of the Canadian Association for 1877 were extinguished.

The Canadian Association and National League, fraternal twins of a sort, each encountered their own respective struggles in their early years. Six of the eight charter members of the National League had folded or been expelled in the first four years of its existence, but the League persisted through its well-documented challenges and controversies, and has cultivated a legacy rich in history and lore. The Canadian Association embraced the game with comparable zeal and commitment, and though it did not survive infancy, its presence and impact on the sport at such a formative time helped solidify Canada’s role and legacy in the evolution of baseball in the nineteenth century.

MARTIN LACOSTE has taught high-school music for over 30 years, but has always had a passion for baseball, whether fondly recalling the Expos from the 1980s or digging into the Maple Leafs from the 1880s. Having been a SABR member in the 1990s, he is excited to again be a member (in the digital era) since 2016.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted:

Newspapers, including British Whig, Guelph Herald, Guelph Mercury, Hamilton Spectator, Hamilton Times, London Advertiser, London Free Press, New York Clipper, Pittsburgh Daily Post, The Globe (Toronto), Toronto Star, and Woodstock Weekly Sentinel.

Genealogical and player data was obtained from a variety of sources, including Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference. com, census records, city directories, vital records, minorleague player files of Reed Howard, Retrosheet.org, and the author’s own player database and genealogical files.

Various ledgers and correspondence from the Sleeman Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph.

Notes

1 William Humber, “It’s Our Game, Too, Neighbor,” in Jane Finnan Dorward, ed., Dominion Ball (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2005), 7.

2 “Base Ball in Canada,” New York Clipper, September 27, 1856:183.

3 “Young Canadian vs. Young America,” New York Clipper, June 11, 1859: 59.

4 William J. Ryczek, Baseball’s First Inning: A History of the National Pastime Through the Civil War (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2014), 205.

5 “Base Ball,” Guelph Mercury, August 26, 1864: 3.

6 “The Base Ball Convention,” Guelph Mercury, April 8, 1876:1.

7 “The Base Ball Convention.”

8 David Fleitz, “Fred Goldsmith,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/fred-goldsmith/.

9 “The Queen’s Birthday,” Guelph Mercury, May 23, 1876: 1.

10 “The Queen’s Birthday.”

11 “The Ball Field,” London Advertiser, May 23, 1876: 1.

12 “The Ball Field.”

13 “The Game in London or ‘How’s That?’,” Guelph Mercury, May 25, 1876: 1.

14 “The Ball Field,” London Advertiser, May 25, 1876: 1.

15 “The Ball Field.”

16 “The Ball Field.”

17 “The Ball Field.”

18 “The Ball Field.”

19 ” Base Ball,” Guelph Mercury, May 29, 1876: 1.

20 “Dominion Day,” British Whig, July 3, 1876: 2.

21 “Dominion Day.”

22 “Dominion Day.”

23 “Dominion Day.”

24 “Dominion Day.”

25 “Dominion Day.”

26 “Base Ball Field,” Guelph Mercury, from the Hamilton Spectator, August 11, 1876: 1.

27 “The Championship Base Ball Match,” London Advertiser, August 10, 1876: 1.

28 “Base Ball Field,” Guelph Mercury, August 12, 1876: 1.

29 “The Championship Base Ball Match,” London Advertiser, August 10, 1876: 1.

30 “The Base Ball Match,” Guelph Mercury, August 10, 1876:1.

31 Bryce’s Canadian Base Ball Guide for 1877 (London: Wm. Bryce, Publisher, 1877), 65.

32 Retrosheet.org.

33 Retrosheet.org.

34 “Yesterday’s Game,” London Advertiser, August 31, 1876:1.

35 “Yesterday’s Game.”

36 Bryce’s Canadian Base Ball Guide for 1877 (London: Wm. Bryce, Publisher, 1877), 65.

37 Bryce’s Canadian Base Ball Guide for 1877 (London: Wm. Bryce, Publisher, 1877), 35.

38 Bryce’s Canadian Base Ball Guide for 1877 (London: Wm. Bryce, Publisher, 1877), 65.

39 “Tecumsehs, of London, the Champions,” Guelph Mercury, October 28, 1876: 1.

40 “Tecumsehs, of London, the Champions.”

41 “Tecumsehs, of London, the Champions.”

42 Bryce’s Canadian Base Ball Guide for 1877 (London: Wm. Bryce, Publisher, 1877), 65.

43 Bryce’s Canadian Base Ball Guide for 1876 (London: Wm. Bryce, Publisher, 1876), 2.

44 Bryce’s Canadian Base Ball Guide for 1876 (London: Wm. Bryce, Publisher, 1876), 2.

45 Bryce’s Canadian Base Ball Guide for 1876 (London: Wm. Bryce, Publisher, 1876), 2.

46 City of London Directory for 1876-77 (London: W.H. Irwin & Co., 1876-77), 115.

47 Brian Martin, The Tecumsehs of the International Association (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2015), 64.

48 Bryce’s Canadian Base Ball Guide for 1876 (London: Wm. Bryce, Publisher, 1876): 1.

49 Library and Archives Canada. Census of Canada, 1871. Ottawa, Ontario: Library and Archives Canada, n.d. RG31-C-1. Statistics Canada Fonds.

50 “William Bryce Dead/Was Long a Merchant,” Toronto Sfar, October 3, 1921: 19.

51 “William Bryce Dead/Was Long a Merchant.”

52 Martin, The Tecumsehs of the International Association, 86.

53 Correspondence from Harry Gorman to George Slee-man, February 26, 1877, Sleeman Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph.

54 Correspondence from Harry Gorman to George Slee-man, February 26, 1877.

55“The Council of Ballists,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, February 22, 1877: 4.

56 “Convention of the Canadian Association,” Guelph Mercury, April 6, 1877: 1.

57 “Convention of the Canadian Association.”

58 “Convention of the Canadian Association.”

59 “Convention of the Canadian Association.”

60 “Base Ball Notes,” Guelph Mercury, May 23, 1877: 1.