Carl Lundgren: The Cubs’ Cold-Weather King

This article was written by Art Ahrens

This article was published in Fall 2019 Baseball Research Journal

All the poetry and folklore of “Tinker to Evers to Chance” notwithstanding, the great Chicago Cubs teams of 1906–10 won their four pennants and two World Series by way of outstanding pitching. The glories of Mordecai “Three Fingered” Brown, Ed Reulbach, Jack Pfiester, and Orval Overall have been widely recognized, and rightfully so. Sadly ignored, however, is right-hander Carl Lundgren, a major contributor to their first two league championship flags (1906–07) and their prior rebuilding period. Not to mention his later accomplishments at the college level.

All the poetry and folklore of “Tinker to Evers to Chance” notwithstanding, the great Chicago Cubs teams of 1906–10 won their four pennants and two World Series by way of outstanding pitching. The glories of Mordecai “Three Fingered” Brown, Ed Reulbach, Jack Pfiester, and Orval Overall have been widely recognized, and rightfully so. Sadly ignored, however, is right-hander Carl Lundgren, a major contributor to their first two league championship flags (1906–07) and their prior rebuilding period. Not to mention his later accomplishments at the college level.

Carl Leonard Lundgren was born February 16, 1880, in Marengo, Illinois — a quiet, picturesque hamlet roughly 55 miles west-northwest of Chicago and home to his mother, Delilah. His mother bore the Scottish surname Renwick, while his father, Pehr Hjalmer Lundgren, was a Swedish immigrant.1 Unlike the Germans and the Irish, the Scandinavians would never take center stage in pre-World War I baseball, but they did play a sizable supporting role, which would be Lundgren’s destiny as well.

After receiving his primary and secondary educations at local public schools, Lundgren entered the University of Illinois in Urbana in September 1898. By the following April he was pitching for the university baseball team, nicknamed the Illinis, under head coach George A. Huff, who would have a profound influence on Lundgren’s future.

Lundgren established himself as an Illini star almost immediately. On April 22, 1899, on the team’s first trip to Chicago, Lundgren defeated the University of Chicago Maroons 4-2 on a frigid Saturday afternoon. This earned him his first major notice, as the Chicago Tribune commented: “Lundgren’s pitching was a surprise to everyone. He did clever work, being steady at critical points, and in the last inning, in spite of the efforts of the rooters to rattle him, he steadied down and took things coolly, sending the ball over the plate as steadily as if he were throwing the first ball of the game.”2

Lundgren was already displaying two earmarks of his future career, namely an ability to remain mentally calm and alert in pressure situations, and being especially strong in cold weather. Carl gained his first campus shutout on Memorial Day over Oberlin College, limiting his opponents to five hits. He aided his 5-0 win with a single, a double, and a run scored. The Tribune simply said, “Illinois played its best home game of the year.”3 Although the Illini came on strong at the end of the season, the University of Michigan won the championship of the Western College Conference (later to be nicknamed the Big Ten), while Huff’s team finished second.4

That summer, Lundgren hurled for the amateur Marengo Athletics, who won 10 games with one tie and no defeats.5 Then it was back to college, as Carl continued to excel both athletically and academically. He became a two-way halfback on the Illini football squad.6 He played football through 1901 and was a member of the Kappa Sigma fraternity.7

Thanks in large part to Lundgren’s pitching, the University of Illinois won the Western Conference pennant in 1900. That year, his catcher was Jake Stahl, who would go on to a career as a journeyman first baseman with several American League clubs and become a World-Series winning manager. During this season, Lundgren enjoyed the easiest win of his college days, a 17-0 romp over Iowa on May 9, 1900.8

Perhaps the rarified championship air was too much for the college boys to handle, as the Illini slipped to fourth in 1901 while Michigan’s Wolverines reclaimed the conference title. In addition to his pitching assignments, Lundgren appeared twice at second base and once in left field. At the season’s close, the Chicago Tribune announced, “Pitcher Lundgren has been selected captain for next year.”9

In Chicago, the city’s befuddled National League team, called concurrently the Orphans (which replaced Colts as their nickname when longtime player-manager Pop Anson was fired in 1898) and the Remnants (due to player raids by the upstart American League), finished sixth in 1901, escaping the cellar by a mere game. Over the winter, the club hired Frank Selee. winner of five flags for the Boston Beaneaters (later the Braves) in the 1890s, as the new field manager. One of Selee’s friends happened to be Huff.10

By coincidence or otherwise, the Chicago Orphans held their 1902 spring training at the Illini campus, enabling Huff to showcase his youthful protégé as well as become an unofficial member of the team’s scouting staff. The massive influx of young players at camp led to a new nickname for the team: the Cubs, though it would take another five years for the name to be used exclusively. Since Selee preferred the old name of Colts, that would be the dominant nickname during his tenure as manager.

As the spring session was winding down, the Colts played nine exhibition games with the Illini, winning five of them. Lundgren appeared in five contests, including a 6-1 complete game triumph over Chicago on April 15, the final game of the series.11

But Lundgren had to finish college first. He made his senior year a grand finale as he led the Illini to the Western Conference pennant once more. On May 12, he pitched his greatest college game, defeating archrival Michigan 2-0 on four hits. Although not a power pitcher, he struck out 14 Wolverines in his complete-game performance.12

After the conference championship had been sewn up, the Illini headed to the east coast to challenge its prestigious teams. Starting and finishing all the games, Lundgren won against Princeton 3-1 on May 24, Yale 10-4 on June 4, and the University of Pennsylvania 11-3 on June 7.13,14,15 His only loss was to Harvard, 2-1 on May 30, in which he was simply outpitched.16

Following Lundgren’s victory over Yale, the Chicago Tribune noted, “The Illini had accomplished a feat never before accomplished by a Western baseball team. It had defeated Yale on her own grounds. Never before at any kind of varsity sport has Yale been defeated by any Western college.” The article also stated that the Illini were to report to New York’s Polo Grounds on the morning of June 5 to practice with the Colts before going to Pennsylvania, an indication that Lundgren might already have been signed.17

Lundgren graduated from the University of Illinois with honors, obtaining a degree in civil engineering, which he would never use.

The new graduate joined the Colts in Cincinnati, making his major-league debut on June 19, 1902. Although it was far from a masterpiece, Lundgren managed to go the route in outlasting Reds ace Frank Hahn, with a final score of 7-5. He also singled and stole a base, which did not figure in the scoring. The Chicago Tribune summarized: “Lundgren. judging by his work, will certainly do. He was against a team on foreign grounds and with about as bad a bunch of rooters as has been seen at League park this season. Notwithstanding all the taunts hurled at him such as ‘Back to college’ and ‘Make him tramp home’ he stuck to his work and when hits were needed to score men he gathered himself together and pulled himself out of the hole…. During the first half of the game the youngster was wild, and gave two bases on balls, made two wild pitches and hit two batsmen. After that he settled down to his work, however, and the Reds found it difficult to single during the remainder of the contest.”18 Apparently, much of it was just a case of common rookie jitters.

Lundgren’s first shutout came on July 8, as he blanked the Giants 2-0, in a game called after seven innings due to both rain and darkness at Chicago’s West Side Grounds. The Chicago Tribune remarked, “The way the visitors were playing, it would have taken them eighty-five innings to score off Lundgren.”19 At Boston on July 30, Carl went 13 innings to subdue the Beaneaters 3-1, in what would remain the longest stint of his career. He had a whitewash going until the bottom of the ninth, when Boston tied it on an error by center fielder Davy Jones. Gaining a second wind, the rookie retired heavy hitters Duff Cooley, Fred Tenney, and Gene Demontreville in order in the last of the 13th to preserve a well-earned victory.20

The 1902 season had been one of experimentation, as no fewer than 38 players tried on a Colt jersey at various times. Lundgren was 9-9 for the year, but his 1.97 ERA (compiled retroactively) was fourth lowest in the National League and best among all rookies. While the team finished in fifth place at 68-69, it was a vast improvement over the previous campaign (which finished 53-86) and Selee felt confident about the future. The manager’s optimism was borne out as the Colts vaulted into contention with a strong third place finish in 1903. They boasted three 20-game winners in Jack Taylor (21-14), Jake Weimer (20-8), and Bob Wicker (20-9). Lundgren, the fourth starter, finished with an 11-9 record.

The specter of scandal reared its head when club president and owner James Hart accused Taylor of throwing games to the White Sox during the crosstown City Series in October. Although the charges were never substantiated, the National League fined Taylor for misconduct. On December 12, 1903, Taylor and catcher Larry McLean were traded to the Cardinals for pitcher Mordecai “Three Fingered” Brown and receiver Jack O’Neill, in one of the best deals the club has ever made.

The departure of Taylor meant more pitching opportunities for Lundgren, as Brown was still an unknown quantity at this point. As Selee’s Colts inched up to second place in 1904, Lundgren began living up to expectations with a 17-10 record. His win total tied him with Bob Wicker for third on the staff behind Weimer (20) and Herb Briggs (19). Lundgren’s repertoire included a variety of curves, a sinker, and an occasional fastball. Streaks of wildness, however, would be a recurrent Achilles Heel.

In Johnny Evers’s 1910 volume Touching Second, coauthored by sportswriter Hugh Fullerton, the following appeared: “Lundgren was quite studious and the ‘Human Icicle,’ one of the most careful observers of batters ever found. He was of the type that studies three aces and a pair of tens before calling — and studies a pair of deuces just as hard. When he calls, he wins, and he pitched wonderful ball for Chicago.”21

The “Human Icicle” phrase referred to his uncanny effectiveness in wintry conditions; sometimes “Human Cucumber” would be substituted instead. He was also nicknamed “Lundy” for obvious reasons.

On September 1, 1904, Lundgren enjoyed his finest outing yet, a 3-0 four hitter over the Brooklyn Superbas (the once and future Dodgers) in Chicago. The Chicago Chronicle beamed, “Carl Lundgren had the Brooklyn baseball players in his inside pocket yesterday afternoon and fairly mopped up the diamond with them.”22 The Chicago Inter-Ocean lauded him as, “one of the best and at the same time one of the most reliable pitchers in the National League.”23

Two days later, Lundgren came through with a perfect game in his personal life when he married Maude Cohoon in his native Marengo.24 Although there would be no children, it was a lasting marriage and by all appearances a happy one. The bride was permitted to accompany her groom on the Colts’ upcoming road trip and he responded with a 4-2 win over the Cardinals on September 5, the second game of a doubleheader sweep. From August 28 to the end of the season, he won seven of his last 10 starts and finished with career highs in innings pitched (242) and strikeouts (106). It had been a satisfying year in more ways than one.

Another one of George Huff’s college discoveries, Ed Reulbach, joined the team in 1905 and quickly became a star hurler. For Lundgren, it would be a bittersweet season. Although he had a 13-4 record, he spent nearly all of June and July on the bench. While he was generally brilliant in cold weather, the converse tended to apply as the temperatures rose. Consequently, he found himself on the sidelines for lengthy periods during the peak of summer. He had already sat out the entire month of August in 1903, save for two garbage-time relief appearances.

After Lundgren was shelled by way of eight hits and five runs on June 4, 1905, in a 5-4 loss to the Pirates in Chicago, in which he only lasted three innings,25 Selee did not use him again until the second outing of an Independence Day twin bill on the home field, in which he edged the Cardinals, 3-2. He made two more appearances that month, both in relief of loser Bob Wicker.26

Major changes at the team’s upper level occurred. As July became August, first baseman Frank Chance replaced the ailing Selee as manager. (Chance had already been virtually running the team as captain throughout July.) Selee retired to Colorado, where he died of tuberculosis four years later. On November 1, James Hart would sell the franchise to Charles W. Murphy, who was financed by Charles P. Taft, half-brother of the future US president William Howard Taft.

Lundgren resumed his spot in the rotation with a bang. Following a 2-1 victory over the Beaneaters on August 4 at West Side Grounds, Carl found himself back on the diamond the next day in a new role. During the morning game of a doubleheader in which Chicago shut out Boston 6-0, umpire James Johnstone was injured by a foul tip. This left him unable to officiate the nightcap, which caused a problem since he was the only ump assigned to the series. Lundgren and Irv Young of the visitors were recruited to do the umpiring in game two as the Colts won again 5-1. The Chicago Chronicle observed that the square-off, “was played without a kick or howl, the teams accepting every decision given by Young and Lundgren without a murmur.”27 And if this were not enough, Lundgren returned to the mound 24 hours later to slam Boston 8-0 to complete a series sweep. Johnstone was still recuperating, so Sam Mertes of New York, on a day off, served as umpire. (The Giants had arrived to begin a four-game set the next day.)28

Now that Frank Chance was at the helm, the team became increasingly known as the Cubs, as that was the name he liked best. By the final month of the season, they had settled into third place as John McGraw’s Giants copped their second straight flag.

On August 17, 1905, the Cubs purchased the contract of pitcher Jack Pfiester from Omaha of the Western League. The left-hander would become prominent in the years to come. But the headline story on September 27 was Lundgren coming within one out of a no-hitter over Brooklyn at the Cubs’ home field. After walking two batters in the second inning, in which he fanned the other three, the Human Icicle set the Superbas down in order, with five more strikeouts along the way. Then, with two out in the top of the ninth, Jimmy Sheckard lifted a blooper which fell between second baseman Johnny Evers and center fielder Jimmy Slagle, rolling past them for a double. In the words of the Chicago Chronicle, “Doc Gessler followed it with a sharp clean drive to center, the only unquestionable hit of the game for Brooklyn,” which scored Sheckard. Gessler then stole second and scored on right fielder Billy Maloney’s two-base muff off the bat of Emil Batch. Batch, in turn, was forced out at second on Jack Hummel’s grounder to end a 7-2 Chicago triumph.29 All the newspaper accounts concurred that Gessler’s single was Brooklyn’s only legitimate hit of the game. If only Sheckard’s Texas Leaguer had stayed in the air a few seconds longer …

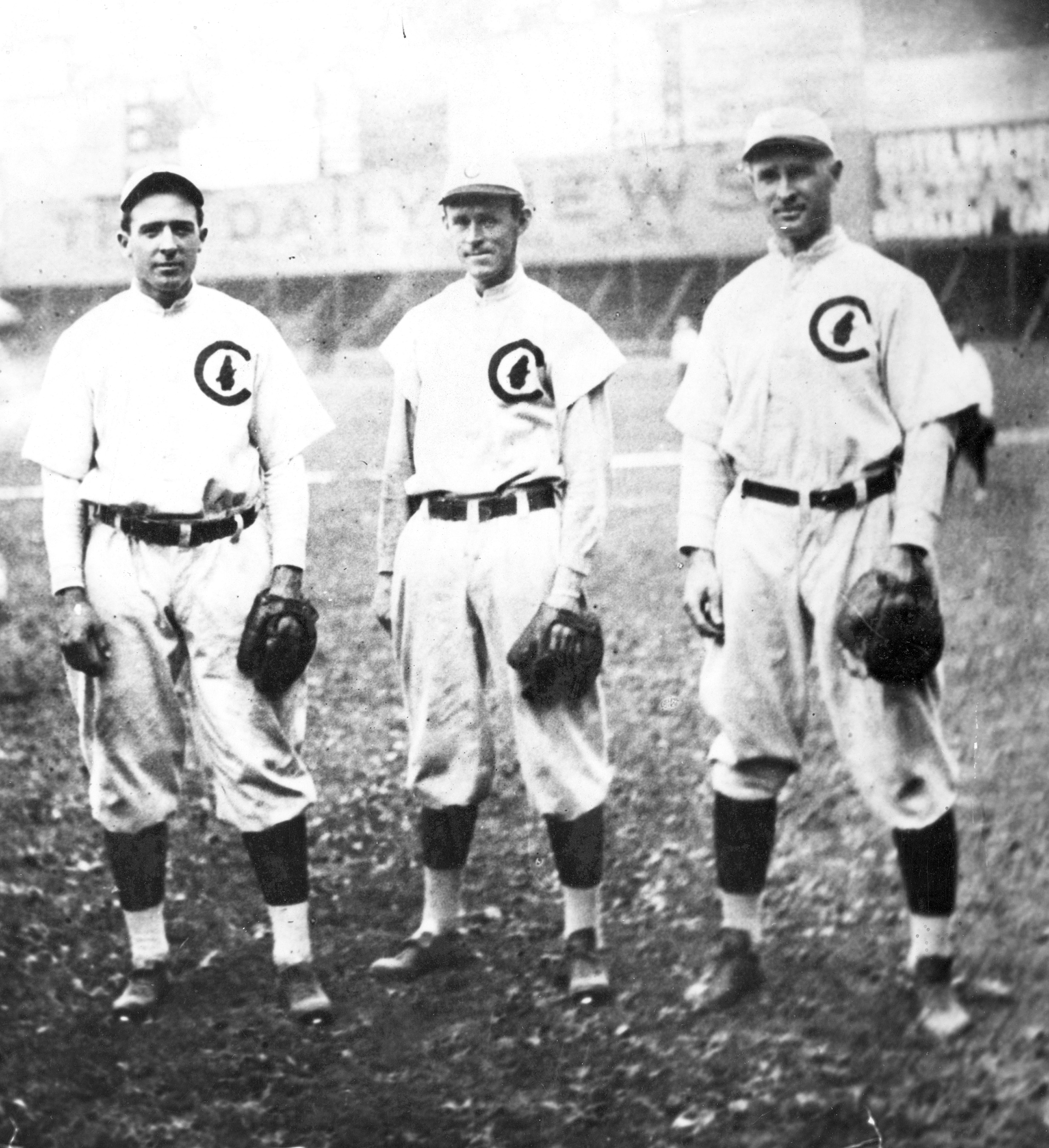

With shortstop Joe Tinker, second baseman Johnny Evers, and first baseman/manager Frank Chance leading the way, the Chicago Cubs dominated the National League from 1906-1910, winning nearly 70 percent of their games, four National League pennants, and two World Series. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

The team that most personified the Cubs of the Tinker to Evers to Chance era coalesced into its definitive form starting in the winter of 1905–06. Third baseman Harry Steinfeldt was acquired from the Reds and outfielder Jimmy Sheckard from the Superbas. Sheckard would be stationed in left field as Frank Schulte was switched to right. They also obtained Pat Moran, who became a dependable back-up catcher to Johnny Kling. The already formidable pitching staff would be enhanced even further with the addition of Orval Overall from the Reds in June 1906 and the reacquisition of Jack Taylor from the Cardinals a month later.

The result was an unstoppable juggernaut that laid all opposition to waste in a record-setting season. And in early 1906, it was Carl Lundgren setting the pace by winning eight of his first nine decisions, highlighted by a seven-game winning streak from April 21 through May 20. Included were back-to-back three-hit shutouts — 8-0 over Brooklyn on May 12 and 1-0 atop Philadelphia in 10 innings on May 16, both at West Side Grounds. After the latter contest, the Chicago Chronicle commented, “Lundgren had everything in the calendar and as control is included in the list no further explanation of his three hit game is necessary.”30

On July 4, 1906, for the first time in their history, the Cubs won both ends of a separate-admission doubleheader by scores of 1-0. The Pirates hosted Chicago as Three Fingered Brown blanked them in the morning game, the lone safety being pitcher Lefty Leifield’s infield single in the third inning. Brown’s act was a tough one to follow, but Lundgren came reasonably close, allowing the Bucs only five hits in the afternoon.

With these victories, the Cubs record stood at 49-21, with Lundgren their winningest pitcher at 13-3. Genuine stardom finally seemed within his grasp, as he was on a trajectory to win 27 or 28 games. At the very least, a 20-plus win season appeared to be a cinch. Fate, however, would decree otherwise.

As the rest of the staff got hotter along with the weather, Lundgren steadily lost his effectiveness. He continued to take his regular turn on the mound through the rest of July, but his offerings were hit hard and he displayed increasing wildness. He ended the month with a 5-2 complete game victory over the Beaneaters at Boston, despite giving up 12 hits and two walks, on July 30. On the same day, Chance announced that he would be using Taylor, Pfiester, and Brown as much as possible, itself an ominous sign.31 Furthermore, since owner Murphy had coughed up money as well as good players to obtain Taylor and Overall, it would not have been wise for the manager to let them sit idle. Consequently, the Human Icicle was the odd man out, despite his 15-5 record.

Lundgren did not make another pitching appearance until August 15 in Chicago, when he almost blew a huge lead in relief. With the score a seemingly safe 10-0 over Brooklyn, Chance rested Brown after the seventh inning and sent Lundgren in to mop up. While the eighth inning was uneventful, the Superbas erupted for seven runs off Lundgren in the ninth on five hits, three walks, and a wild pitch. He walked in one run while another two plated on Evers’s throwing error.32 Although the Cubs hung on to win 10-7, Lundgren’s outing could not have inspired confidence.

Lundgren did not get a return assignment until the second game of an August 24 doubleheader with the Phillies, probably because Chance had no one else to pitch. His 7-3 victory was due more to Cub bat work than his own finesse, as Lundgren allowed nine hits and three free passes.33 Again. no assurance builder…

In less than a week. Lundgren was back on the field for three straight games as a replacement umpire. With the Reds in town on Friday August 31, scheduled umpire Robert Emslie was down with suspected food poisoning, so Lundgren shared the duties with Emslie’s partner James Johnstone. Lundgren showed no bias in favor of his team but did not need to either, as Overall handled the Queen City by a score of 8-1. The next day, the Cardinals came to Chicago as Johnstone joined Emslie on the sick list. Now the Cub pitcher was joined in officiating by St. Louis receiver Peter Noonan in another 8-1 Chicago triumph behind the red-hot Brown. The regular referees remained ill on September 2 as Lundgren worked with Cardinal hurler Ed Karger. The Cardinals won 5-2 to halt the Cubs’ winning streak at 14 games. To quote the Chicago Chronicle, “As usual, when pay players handle the game, there was little kicking.”34

The Cubs’ pennant clincher came on September 19 with a 3-1 Reulbach win at Boston for their 106th victory of the season, tying the record set by the Giants two years earlier. Five days later, in game one of a now-meaningless doubleheader at the Polo Grounds, Brown had to exit the game on account of muscle spasms with one out in the fifth inning and Giant runners at first and second. Chance called on Lundgren to relieve him and he came through with his best pitching job in over two months. Spike Shannon’s single knocked home Bill Dahlen from second, but Lundgren slammed the door on New York thereafter, holding them scoreless and whiffing five to preserve a 6-2 win. Although Brown was credited with the victory, under today’s rules Lundgren would have received it, as starter Brown did not finish the fifth inning. The Chicago Daily News beamed, “Lundgren showed yesterday that he had returned to form again and that he will be in shape to do a lot of hard work in the world’s series. This cool weather has braced him up wonderfully.”35 On September 27 he received his first start since August 24, losing to the Superbas 4-0 at Brooklyn. It was deceptive, as Brooklyn did all of its scoring in the first inning; from that point on, Lundgren hurled nothing but goose eggs.36

As the season drew to a close, Lundgren finished on a high note. In the morning game of a doubleheader at Philadelphia on October 1, the cold weather man gave what might have been the finest performance of his career. He allowed two singles, neither of which resulted in an advancement. There was neither a walk nor a hit batsman. The best description came from Charles Dryden in the Chicago Tribune: “So completely were the Phillies vanquished that not a gent was left on base. Spud this is what the Tribune called the team in 1906 Lundgren was a human hurricane that swept them off the map. Gook Sherry Magee singled in the second and was caught stealing. Paul Sentell combed a safety in the seventh. ‘Kitty’ Bill Bransfield forced him and was thrown out stealing. The Spuds played a perfect game and Lundgren walked no one.”37

As a result, Lundgren faced the minimum 27 batters in a 4-0 victory. In game two, Ed Reulbach edged the Quakers 4-3, in a match called after six innings by mutual consent. It was Reulbach’s 12th win in a row, hoisting his final record to 19-4 for a league-leading .826 average. The twin wins were the Cubs’ 114th and 115th of the campaign.

Record victory number 116 (not matched until 2001 by the Seattle Mariners with a longer schedule) came in Pittsburgh on October 4 as Jack Pfiester got the win against the Pirates 4-0 for his 20th triumph. Lundgren contributed to this historic affair also, playing second base in place of Evers, who was filling in for the resting Harry Steinfeldt at third. In the ninth inning, Lundgren’s double to center field sent Chance across the plate for Chicago’s third run, after which Lundgren himself scored on Evers’s infield hit and Joe Nealon’s errant throw. Defensively, he made no errors, two assists, and three putouts.38

For the season. Lundgren was 17-6 with a 2.21 ERA and five shutouts. Although an enviable showing, it was a disappointment compared to his awesome start. Brown had emerged as the dominant man on the corps with a 26-6 ledger plus a league leading ERA of 1.04 and nine shutouts. Taylor and Overall each checked in at 12-3 after donning Cub flannels.

In the meantime, the “Hitless Wonder” White Sox had captured the American League flag to give Chicago a crosstown World Series, which the city has not witnessed since. As their feeble .230 batting average was lowest in their league, they were three-to-one underdogs with the oddsmakers. Now it was time for Frank Chance to select his pitchers.

The “Peerless Leader” appears to have scratched Lundgren because the White Sox had roughed him up somewhat in the 1905 City Series, which the Cubs won in five games. As for Jack Taylor, Chance feared that if Taylor pitched and lost, the game-throwing charges would resurface.39 Both would sit on the bench for the entire series, as Chance went with Brown, Reulbach, Pfiester, and Overall.

After the first four contests, the World Series was tied at two wins apiece. The Hitless Wonders suddenly became sluggers in the fifth game, belting Reulbach, Pfiester (credited with the loss), and Overall to outlast the Cubs 8-6, despite committing six errors. In game six, Brown started his third game in six days, and on just one day’s rest. Thoroughly exhausted, Brown surrendered seven runs in one-and-two-thirds innings before being sent to the showers. Overall managed to stop most of the bleeding in relief, but it was too late, as the Sox coasted to an 8-3 victory and a World Series title. The next day, the Chicago Daily News remarked, “Some criticism of Chance is heard for permitting Brown to remain in the box as long as he did yesterday, and also for not using Lundgren at any time in the series.”40 Giants manager John McGraw noted, “After Lundgren and Taylor had helped the Cubs win the pennant I believe Manager Chance should have used one or both of them in the world’s series.”41

Doubtlessly, countless Cub fans echoed the same sentiments as they drowned their sorrows in neighborhood saloons. It should also be reiterated that in his last three appearances during the regular season, Lundgren had pitched brilliantly, except for one shaky inning. Furthermore, the first three games of the World Series had been played in temperatures which were far below normal — precisely the kind of weather that Lundgren thrived in. The atmospheric conditions for the final three contests, while seasonably pleasant for October, were still nowhere near a stifling heat wave. When these elements were factored into the equation, it would have made perfect sense for Chance to have given Lundgren at least one start, regardless of his showing in the previous year’s City Series.

One thing is certain — Lundgren could hardly have fared any worse than the others had in the last two games. Chance’s intransigence might have cost the Cubs the Series.

As any native Chicagoan can verify, springtime in the Windy City is nearly always a miserable, watered-down version of winter, and 1907 was a bad one even by those standards. After the Cubs and their fans shivered through a 6-1 opening day victory over the Cardinals on April 11, the next two games were snowed out. At game time on April 14, it was 34 degrees in Chicago with a frigid west wind that made it feel at least 10 degrees cooler. Patches of snow dotted the spacious outfield at West Side Grounds. It was in these Lundgren-friendly environs that the winter air wizard embarked on his finest season with a four-hit 2-0 win versus St. Louis. In referring to the day as “football weather,” the Chicago Chronicle called Lundgren, “the government bonds as a chilly day pitcher.”42

The bad weather followed the Cubs on their first trip east as Lundgren downed the Pirates on April 20 by a score of 5-1, in a game halted after eight innings because of the cold. Back in Chicago on May 4, conditions had moderated ever so slightly with a 40-degree day and a northeast wind in Old Man Winter’s last, vengeful gasp. Although he gave up six hits and seven walks, Lundgren was able to blank the Pirates 1-0. The Cubs managed but two hits, both by Artie Hofman, whose fourth-inning single drove in the solitary run. As the Chicago Tribune put it, “Tradition says Lundgren is at his best when the frost is on the pumpkin.”43

Lundgren was even effective on days when he was not supposed to be. The temperature was 86 with a dense humidity on June 22 when he posted a 3-0 six-hitter over the Cardinals on his home turf. The Chicago Inter-Ocean kiddingly commented, “while it was not cold enough to please the arctic curver, he managed to get away with the better end of the argument.”44 He would eventually spend some time on the sidelines during the heat, but not as much as during the previous two seasons.

In another runaway race, the Cubs took the flag with a 107-45 record, good for a 17-game margin above the second-place Pirates. Despite going winless between July 15 and August 27, Lundgren closed out with 18 wins against seven defeats. Two of his losses were by 1-0 scores and another by 2-1, so with a few timely hits his record could easily have been 21-4. His minuscule 1.17 ERA was a hairsbreadth behind Jack Pfiester’s circuit-best 1.15, while his seven shutouts ranked third to Orval Overall’s and Giant Christy Mathewson’s league-best eight. Lundgren was the stingiest in the league in hits per nine innings (5.65) and opponent’s batting average (.185). The sole area where one could find fault with his account was that his walks outnumbered strikeouts, 92 to 84, though obviously the damage done was minimal.

His stellar showing notwithstanding. Lundgren was again bypassed for the 1907 World Series against Detroit. On October 6, Chance announced that Overall, Pfiester, Reulbach, and Brown would be his starters.45 Reulbach (17) and Pfiester (14) had both won fewer games than Lundgren. Even Brown looked like a question mark, having seen little action since he strained a muscle in his pitching arm in late August.46 One can only guess that, for whatever reason, Chance did not have faith in Lundgren when it came to the “money games.”

As it turned out, Lundgren’s services were not needed. After the first game had been called as a tie when the sun went down after 12 innings, the Cubs skinned the Tigers in four straight to win the World Series. The question of whether or not Chance would have used Lundgren had the series extended any further remains one of baseball’s unsolved mysteries.

The 1908 season seemed to begin well enough for Lundgren, as he won six of his first nine decisions. Ominously, however, he was having problems finding the plate even in the games he won. In his first start of the year, April 16, he went into the ninth inning at Cincinnati with a 7-1 lead, then promptly issued 11 straight balls to start the frame. Luckily, he was able to hold onto a 7-4 win.47

One of Lundgren’s most subline moments came nearly two months hence. On a cool day with intermittent rain at Brooklyn’s Washington Park on June 11, Lundgren and Irvin “Kaiser” Wilhelm of the Trolley Dodgers, as they were once again being called, held each other to a 1-1 draw after 10 innings. In the top of the 11th, Cub catcher Johnny Kling singled, then took second on Joe Tinker’s sacrifice bunt. Chance let Lundgren bat for himself and he “cracked out a beautiful biff a long single along the third base line and tallied J. Kling with the winning run.”48 He then retired all three Brooklynites on long fly balls in the bottom of the inning for a 2-1 triumph. For Lundgren, whose lifetime batting average was .157, it was the only time in the majors that he won his own game with his bat in the final round. Hopefully he savored it, for the glory would be ephemeral.

Seven days later the Cubs started Ed Reulbach in a game against the Giants at the Polo Grounds. But after Reulbach walked the first two batters in the third, Chance yanked him in favor of a half-warmed-up Lundgren, who didn’t fare much better. Lundgren gave up three runs on seven hits and two walks in seven relief innings, but Chicago hung to a 7-5 win in which “the pitching kept the club in hot water all the time.”49 It would be Lundgren’s last victory in the big time.

From that point on it was all downhill, as Lundgren lost his next six starts and had two decisionless relief appearances, all of which were ineffective in varying degrees. His control, never one of his strong areas to begin with, had now vanished completely. After an 8-3 home loss to the Phillies on August 18, in which Lundgren was knocked out of the box in the sixth inning,50 he spent the remainder of the year as a dugout spectator.

When the Cubs began their final scheduled road trip on September 10, Lundgren, Chick Fraser, Kid Durbin, and the injured Jimmy Sheckard remained in Chicago.51 Fraser and Sheckard rejoined the team in Cincinnati on September 29.52

After the most nail-biting and controversial pennant race in history, the Cubs met the Tigers again for the 1908 World Series. Once more, the Bruins tamed the Bengals in five games as Lundgren observed the proceedings from the sidelines. This time, Chance’s decision not to use him was understandable.

Still, Chance was not ready to give up on Lundgren quite yet. He made two more token appearances in April 1909. The first was a relief stint for loser Zerah “Rip” Hagerman in a 3-1 loss to the Cardinals on April 16 at Chicago, and the second a start versus the same team in St. Louis on the 23rd. In the latter, he lasted three-and-one-third innings, allowing four runs on six hits and three walks before Hagerman relieved him. St. Louis went on to a 6-3 victory as Lundgren was tagged with the loss in his final bow as a major leaguer.53 Four days later he was placed on waivers, exiting with a 91-55 record. In the generally cooler months of April, May, September, and October, he was a juicy 53-26. Eleven of his 19 shutouts occurred during these months as well.

While the release came as no surprise, his teammates were sad to see Lundgren leave, as he had always been popular. The news stories all agreed that there appeared to be nothing wrong with his arm, although some opined, “he seems to have lost confidence in himself.”54 How Lundgren lost his effectiveness so totally at such a young age will probably never be known after the passage of more than a century. And perhaps an occult-minded researcher will theorize that “the curse of Carl Lundgren” prevented the Cubs from winning a World Series for more than a century after he left the team.

On May 9, 1909, the Chicago Tribune reported: “Carl Lundgren, dean of the Cub pitching staff in point of continuous service, was disposed of to the Brooklyn club yesterday and president Ebbetts in making the purchase announced he would seek waivers on Carl immediately with a view to disposing of him to the Toronto club of the Eastern League…”55 After briefly refusing to report, Lundgren joined the 1909 Toronto club and went 1–3 for the Maple Leafs before being suspended by manager Joe Kelley.56 Several weeks later, Toronto sold Lundgren to Kansas City of the American Association, but rather than join the Blues, Lundgren apparently spent the remainder of 1909 pitching in semi-pro ball in the Chicago area although details of those exploits have yet to be uncovered.57

Lundgren rejoined Toronto in 1910, then over the next three years drifted to Hartford of the Connecticut League, then Troy of the New York State League.Mobile of the Southern Association nearly signed him but in the end did not because of his sore arm. However, in 1912 and 1913 he also served as pitching coach at Princeton University. This would be a turning point in his baseball life.

In August 1913, Branch Rickey resigned his post as head baseball coach at the University of Michigan to become field manager of the St. Louis Browns. On August 12, the school hired Lundgren as his successor, to report the following February.58

During Lundgren’s first three years at Michigan, the Wolverines played as an independent team, having left the Western College Conference several years earlier. One of Lundgren’s players in his first two seasons at the helm was future Hall of Famer George Sisler, then primarily a pitcher. On May 8, 1915, Sisler allowed five hits and fanned 20 batters in a game against Syracuse that was called as a 2-2 tie after 13 innings due to rain in Ann Arbor, Michigan.59 Upon his graduation a month later Sisler would join the St. Louis Browns and become the greatest player in the St. Louis Browns annals, such as they were.

Michigan canceled its 1917 baseball season due to the Great War, then rejoined the Big Ten the following year. It was then that Lundgren’s coaching career really took off, as his teams captured Western Conference titles in 1918, 1919, and 1920, with records of 9-1, 9-0, and 9-1. Ace pitcher Vernon “Slicker” Parks hurled a 7-0 no-hitter over Lundgren’s alma mater, the Illini, on May 31, 1919, to clinch that year’s pennant.60 Parks would later enjoy a brief stay in the majors, as would shortstop Kenneth “Nike” Knode, who hit a home run in the second inning.61

Following the 1920 championship, Lundgren spent the summer as a pitching instructor for the Cardinals.62 The Redbirds went from 54-83 in 1919 to 75-79 in 1920 to 87-66 in 1921. How much of the improvement was the result of Lundgren’s pitching tips as opposed to the bats of Rogers Hornsby and others is open to debate.

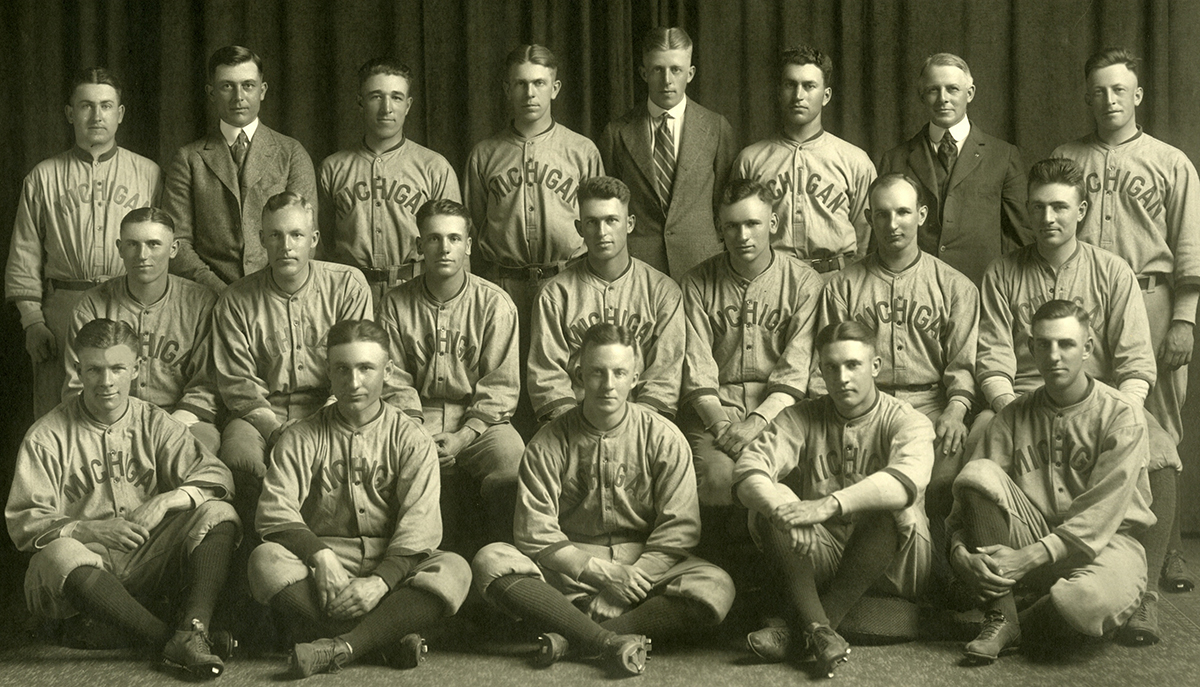

The 1920 Michigan Wolverines baseball team, with head coach Carl Lundgren (back row, second from left), won its third consecutive Big Ten Conference championship. (BENTLEY HISTORICAL LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN)

George Huff, now the athletic director at the University of Illinois, had retired from active coaching. Impressed by Lundgren’s success at Michigan, he persuaded his former pupil to return to his old school to run the baseball team. The results were immediate: Lundgren’s Illini copped conference pennants in 1921 (10-1, with the only loss being the final game of the season) and 1922 (8-2). During a 7-3 win over Michigan on May 20, 1922, Lundgren’s lineup boasted four future major leaguers: Otto Vogel, Harry McCurdy, Dick Reichle, and Wally Roettger.63 Vogel would later be a varsity coach, first at Iowa and later at Northwestern (Evanston, Illinois).64 McCurdy became a footnote in Phillies trivia by leading the National League in pinch hits with 15 in 1933. Roettger, after eight major league seasons as mainly a second-string outfielder, would succeed Lundgren as Illinois’ baseball coach.

With five straight championships under his belt, Lundgren had emerged as college baseball’s equivalent of fellow Scandinavian Knute Rockne, the legendary Notre Dame football coach. Huff called him, “the greatest of all college baseball coaches.”65 In a fawning writeup entitled, “A Maker of Men” in the May 1923 Sporting Life (no relation to the paper which ceased publication in 1917), Gene Kessler praised Lundgren as, “the kind who says little and thinks a lot,” “a self-repressing genius,” “a man of the highest integrity,” “especially noted for his ability to bring the fine qualities out in coaching the young pitchers,” and “does not look a day older than when he was pitching winning baseball for the Chicago Cubs.” Unfortunately, the piece did not delve into his strategies as a coach other than, “Lundgren is a baseball martinet but not a driver. He has strict discipline, but handles his men in a psychological manner.”66 This, of course, could have meant anything. Despite the syrupy tone of the article, at least some of the adulation had to have been deserved in light of Lundgren’s track record.

It also appears to have been an early precursor of the “Sports Illustrated jinx,” as following the publication of that piece, Illinois lost two of its last three games to finish third in the Big Ten standings while Michigan took that season’s pennant. Over the next three years. the Illini were competent but unexceptional, winding up fifth in 1924, sixth the following year, then up to fourth in 1926.

Not until 1927 did Illinois repeat as champions, and even then they had to share the title with Iowa, as the Hawkeyes won their final game on May 30 to tie the Illini at 7-3.67 (At that time, there were no playoffs in college baseball, rainouts were not rescheduled, and ties were neither resumed nor replayed.) Lundgren’s team then slipped to seventh in 1928 and fourth the year after.

Starting in 1930, Illinois became a perennial contender again as Lundgren, now the assistant athletic director as well as baseball coach, began his second-most productive period. In an exciting, heavy-hitting season, Wisconsin’s Badgers won the Western Conference flag while Illinois finished a close second in the 1930 race. The juiced-up baseball employed by the majors apparently filtered its way down to varsity ball, as the Illini scored more than 10 runs in five of their eight conference wins, topped off by a 14-0 massacre of Northwestern on April 28.68 And one of the Badgers’ nine victories was a 16-12 slugfest, also versus Northwestern, on May 7.69

Illinois pulled in at 8-2 again in the Big Ten pennant drive in 1931, and this time it was good enough for the flag as they edged out Chicago, which finished at 8-3. One of the Illini victories was a 3-2 edging of Chicago on their turf on April 18, defeating Maroon ace Roy Henshaw.70 Henshaw would have an eight-year stay in the majors, helping the Cubs win the 1935 pennant with a 13-5 record. Illini catcher Paul Chervinko went on to play as a third-stringer for the Dodgers from 1937–38.

Following the championship, Illinois finished second the next two seasons. In 1933, the Illini had the winningest record (8-2) in the Western Conference, but Minnesota came through with the best winning average (6-1, .857). Two of Illinois’ victories were back-to-back blowouts on successive days: 15-4 against Northwestern on May 16, and 20-7 over Chicago on the 17th, both away from home.71,72

Lundgren would not be denied a pennant in 1934 as the Illini assembled a 9-1 finish for his fifth championship in Urbana. Their only loss came on May 5 at Ann Arbor, as old nemesis Michigan’s Francis “Whitey” Wistert fanned 10 Illini in a 4-1 win.73 Before the year was over, Wistert would have a barely visible fling in the majors with two mound trips for the Reds. Concurrently, Fred Frink, an Illini outfielder, experienced an equally microscopic career with the Phillies, appearing in two games as a late-inning replacement.

It had been Illinois’ winningest season since 1921. In midsummer, Carl and Maude Lundgren vacationed in Canada. On August 21, 1934, they were attending a Kiwanis club picnic in their hometown of Marengo when the coach began suffering nausea and chest pains in the late afternoon. Taken to the nearby home of relatives, Lundgren died of heart failure at 9:15 pm.74

As he had apparently been in normal health, Lundgren’s passing was a shock to all who knew him. Survived by his wife and two sisters, he was buried in Marengo City Cemetery following a brief service. In Big Ten competition from 1918 through 1934, Lundgren’s teams had posted 126 wins against 46 losses (27-2 at Michigan and 99-44 at Illinois) for a .733 winning average. He never led a team to a losing record — his poorest showing in the Western Conference was 6-6 in 1928.

Still a well-known figure at the time of his death, Lundgren’s role in the last great Cubs team was gradually forgotten. Three-Finger Brown’s handicap helped enable him to win 20 games six straight years en route to 239 career victories and eventual enshrinement in Cooperstown. Ed Reulbach led the league in winning percentage for three consecutive seasons, and is the only pitcher in history to master a shutout doubleheader. Jack Pfiester, who won 20 fewer games than Lundgren in the majors, is remembered as the “Giant Killer” for winning 15 of 20 decisions against the New York team. Jack Taylor hurled an incredible 187 consecutive complete-game starts between 1901 and 1906. Orval Overall, a two-time 20-game winner, topped the National League in strikeouts in 1909. Lundgren, unfortunately, had no such eye-popping feathers in his cap. And as a quiet, scholarly individual, he was neither colorful nor controversial. Nevertheless, his achievements as a pitcher and varsity coach speak for themselves. In 35 years of baseball, Lundgren left a legacy to be proud of. As such, his memory deserves a better fate.

ART AHRENS is a longtime contributor to SABR’s publications, spanning 1973 to present. He lives in Chicago.

Notes

1 Bill Lamb, “Carl Lundgren,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/acf35363

2 Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1899.

3 Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1899.

4 Chicago Tribune, June 7, 1899.

5 Marengo Beacon-News, January 23, 1975.

6 Lamb, op. cit.

7 Unidentified newspaper clipping, ca. 1906, in Lundgren’s Hall of Fame file.

8 Chicago Tribune, May 10, 1990.

9 Chicago Tribune, June 17, 1901.

10 Gil Bogen, Johnny Kling: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson: McFarland & Co., 2006), 51.

11 Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1902.

12 Chicago Tribune, May 13, 1902.

13 Chicago Tribune, May 25, 1902.

14 Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1902.

15 Chicago Tribune, June 8, 1902.

16 Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1902.

17 Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1902.

18 Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1902.

19 Chicago Tribune, July 9, 1902.

20 Chicago Tribune, July 31, 1902.

21 John J. Evers and Hugh S. Fullerson, Touching Second (Jefferson: McFarland & Co., 2005), as quoted in Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York: St. Martin’s, 1996), 100.

22 Chicago Chronicle, September 2, 1904.

23 Chicago Inter-Ocean, September 2, 1904.

24 Marengo Beacon-News, op. cit.

25 Chicago Chronicle, June 5, 1905.

26 Chicago Chronicle, July 14, 1905 and July 21, 1905.

27 Chicago Chronicle, August 6, 1905.

28 Chicago Chronicle, August 7, 1905.

29 Chicago Chronicle, September 28, 1905.

30 Chicago Chronicle, May 17, 1906.

31 Chicago Chronicle, July 31, 1906.

32 Chicago Inter-Ocean, August 16, 1906.

33 Chicago Inter-Ocean, August 25, 1906.

34 Chicago Chronicle, September 3, 1906.

35 Chicago Daily News, September 25, 1906.

36 Chicago Daily News, September 27, 1906.

37 Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1906.

38 Chicago Tribune, October 5, 1906.

39 Lowell L. Blaisdell, “Trouble and Jack Taylor,” The National Pastime (Cleveland: SABR, 1996), 135.

40 Chicago Daily News, October 15, 1906.

41 Chicago Daily News and Chicago Journal, October 15, 1906 — both papers carried the same McGraw quote.

42 Chicago Chronicle, April 15, 1907.

43 Chicago Tribune, May 5, 1907.

44 Chicago Inter-Ocean, June 23, 1907.

45 Chicago Daily News, October 7, 1907.

46 Cindy Thomson and Scott Brown, Three Finger (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006), 49.

47 George R. Matthews, When the Cubs Won It All (Jefferson: McFarland & Co., 2009), 33.

48 Chicago Inter-Ocean, June 12, 1908.

49 Chicago Daily News, June 18, 1908.

50Chicago Daily News, August 18, 1908.

51 Matthews, 149.

52 Matthews, 171.

53 Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1909.

54 Chicago American, Chicago Journal, and Chicago Record-Herald, April 28, 1909 — all three papers had the same quote.

55 Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1909.

56 Sporting Life, June 26, 1909; Lamb, op. cit.

57 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Lundgren’s Hall of Fame file. The year appears to be 1909, as the wording is, “He is now pitching independent ball in and around Chicago.”

58 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Lundgren’s Hall of Fame file.

59 Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1915.

60 Chicago Tribune, June 1, 1919.

61 Chicago Tribune, June 1, 1919.

62 Gene Kessler, “A Maker of Men,” Sporting Life (May 1923), 47.

63 Chicago Tribune, May 21, 1922.

64 Otto Vogel obituary, Chicago Tribune, August 22, 1934.

65 Kessler, “A Maker of Men.”

66 Kessler, “A Maker of Men.”

67 Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1927.

68 Chicago Tribune, April 29, 1930

69 Chicago Tribune, May 8, 1930.

70 Chicago Tribune, April 19, 1931.

71 Chicago Tribune, May 17, 1933.

72 Chicago Tribune, May 18, 1933.

73 Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1934.

74 Lundgren’s death certificate in his Hall of Fame file.