Champions, Tantrums and Bad Umps: The 1885 “World Series”

This article was written by Paul E. Doutrich

This article was published in Fall 2017 Baseball Research Journal

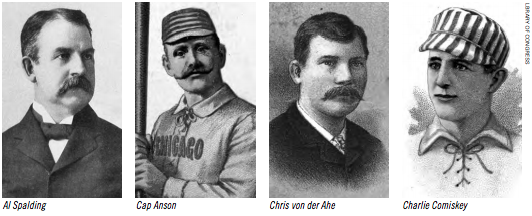

For more than a century the World Series has been an integral part of American culture. It has become a final celebration of the more than 2,700 games that connect the early spring with the late fall. The annual ritual of the best team in the American League facing the best of the National League has taken place every season since 1903 except in1904 when John McGraw refused to play his American League rivals and in 1994 due to a players’ strike. However, one of the earliest blooms of the World Series as we know it flowered eighteen years earlier, in 1885. Two strong-willed and fiercely competitive team owners—Christian von der Ahe, president of the St. Louis Browns, and his Chicago White Stockings counterpart, Albert Spalding—each ponied up $500 and agreed to a winner-take-all series of games. The seven games that followed marked a significant step toward the institutionalization of today’s annual competition to determine which team and league carries the title as the world’s best.1

In October 1885, Chris von der Ahe found himself on the verge of notable success. His American Association champion St. Louis Browns team was about to begin a series with the National League champion Chicago White Stockings that both club owners had agreed would be baseball’s world championship. Chicago was among the charter members of the National League, which was the premier professional baseball league. Most considered the American Association a distant second.

A year before, the National League champion Providence had agreed to play the American Association winner, the Metropolitans, in a hastily arranged series. Advertised as a “Championship of the United States,” the matchup was the first time that the two league winners had ever met for a championship. Though more games were initially considered, the three that were played did not turn out well for the American Association team. On three cold, late October afternoons, in front of disappointingly small crowds, the Grays demonstrated their superiority in all phases of the game and handily dispatched the Metropolitans. The games clearly established the National League’s superiority. Now it was the Browns’ chance to prove that wrong.2

No one loved winning more than Chris von der Ahe. His had been a success story from the time he first stepped onto a New York City dock in 1867. Then he was a German teenager, alone, with empty pockets and no prospects. The city fed on young, unsophisticated immigrants like him. But in just eighteen years, through luck and pluck (mostly pluck), he had climbed from grocery clerk to successful St. Louis entrepreneur and community leader. At the core of his enterprises was a very popular saloon and beer garden in the heart of his city’s ever growing German district.3

When he became the Browns’ president in 1880, von der Ahe knew little about baseball.4 What he did know was how to turn a profit, and he saw in his new endeavor an opportunity to make lots of profit. The Brown Stockings had been a professional team since 1878, but von der Ahe explored ways to make them a moneymaker. In 1881 he joined more than a dozen others in forming the Sportsman’s Park and Club Association and investing in a neighborhood sporting park (Sportsman’s Park).5 Encouraged by one of his bartenders and long-time professional ballplayer, Ned Cuthbert, Association president von der Ahe became a guiding force in rejuvenating professional baseball in St. Louis.

After reconstructing the park (including adding a beer garden in right field) in 1881 and enlisting the assistance of Alfred Spink, a local newspaper reporter and later a founder of Sporting News, von der Ahe made his next move in monetizing the Browns. Encouraged by a summer of numerous successful exhibition games, he and Spink joined five other baseball financiers in establishing the American Association the following winter.6 Composed of clubs from cities excluded by the National League, the Association sought to rival the National League if not in talent at least in entertaining patrons and in generating revenue. And eventually revenue would attract talent.7

During the league’s first three years von der Ahe’s club built a respectable record. After finishing a dismal fifth during the inaugural season, the Browns came within a game of the league championship the following season. In 1884 the team finished fourth, eight games back, in a league that had expanded to twelve clubs.8 Despite his team’s competitiveness, von der Ahe was not satisfied.

The Browns’ president was not a particularly patient man. By 1885 he expected a championship. Fortunately an unforeseen change late in the 1884 season proved to be a crucial step in that direction. Throughout the season von der Ahe’s relationship with manager Jimmy Williams had been fraying. In early September, Williams resigned. It was a scenario reminiscent of the previous season when Ted Sullivan—considered to be among the most knowledgeable men in the game—had quit as Browns manager during a roaring late-night argument with his employer. In both cases the source of the conflict was von der Ahe’s insistence on making crucial decisions both on and off the field, even though he still knew little about the game. In 1884, as he had done when Sullivan left, the Browns’ president shifted managerial responsibilities to his young first baseman, team captain Charlie Comiskey. This time, however, Comiskey retained his new duties.

When he officially became player-manager, Comiskey was only twenty-five years old—younger than most of his teammates. He had, nevertheless, earned their respect. A fierce competitor, he was ready to do whatever needed to be done to win games.9 As manager he relentlessly sought to pressure opponents into mistakes. He employed aggressive play on the base paths, pushing his players to take an extra base or steal a base whenever it was advantageous.

In the field Comiskey expected defensive excellence. He was also one of those who introduced a change that revolutionized the way his position was played. Previously first basemen had played close to the bag at all times. Comiskey instead played well off the bag and several steps toward second, enabling him to be more active defensively. Within several years Comiskey’s style of play became the standard positioning for first basemen (and, of course, still is).10

Off the field he was a true student of the game who diligently studied opposing hitters, pitchers, and fielders, constantly looking for weaknesses that could be exploited. His tactics also included needling opponents and “kicking” (assertively disputing) umpire decisions. His club developed some of the era’s most notorious bench jockeys. In terms of his personal demeanor, Comiskey was a disciplined ball player whose lifestyle was designed to prepare him for games. Postgame carousing, a standard endeavor of many ballplayers, was something he spurned—much to the satisfaction of von der Ahe, who considered off-the-field discipline essential for a winning team.

Von der Ahe got what he had hoped for with Comiskey. In 1885 the Browns dominated the American Association. During the first two cold, dreary weeks of the season, the team won as many as it lost. However, as the St. Louis weather heated up in late April, so did the Browns. The team concluded its first home stand by splitting a pair of games with the Louisvilles and defeating Pittsburgh. The loss to Louisville was the last time Comiskey’s crew would lose a home game until July 18, a streak of 27 games. By the time the Sportsman’s Park winning streak ended, the Browns, despite winning only 17 of 31 games on the road, had built a comfortable 9½ game lead over the rest of the league. That lead grew to 16 games by the end of the season.11

But the League championship was not enough for Chris von der Ahe. Eager to parlay his team’s success into something bigger, he challenged Spalding and the White Stockings. The Metropolitans and Grays’ three-game series the year before had not been sanctioned by their leagues and, therefore, was not considered a championship series by either league despite being advertised as such. The 1884 games were simply postseason exhibition games, arranged to generate a little extra revenue. Von der Ahe’s motives were more encompassing. He proposed that the series would determine the best team in the world. He saw an opportunity to promote the American Association as well as his own status as one of baseball’s preeminent executives. Spalding considered the proposal to be a brash challenge to his White Stockings and the National League, but he recognized it was a challenge that could not be dismissed. Smugly confident his team could not lose to the upstarts, he accepted von der Ahe’s proposal. Later he would claim that he considered the games to be merely potentially profitable exhibitions from the beginning.

Unlike von der Ahe, Albert Spalding was a baseball man. He grew up in a fairly affluent family eighty miles west of Chicago—in Rockford, Illinois, where he learned the game as a youngster. His climb through baseball’s hierarchy began when he was seventeen and pitched his local team to a notable victory over the Nationals of Washington, one of the better teams outside New York and the first eastern team to travel west. A few years later he was hired by the legendary Harry Wright to pitch for his Boston Red Stockings in the new National Association. Spalding became the game’s preeminent hurler. With the creation of the National League in 1876, he jumped to the Chicago White Stockings where he became the team captain, later the team secretary, team president, and ultimately the team’s principal owner. Meanwhile, he had begun to build a sporting goods empire. By the time of von der Ahe’s challenge, Spalding was among the most influential men in baseball.12

Aside from their entrepreneurial nature, the two team owners had sharply contrasting personalities. Spalding was a nativist Republican who intended for his game to help fortify core American moral principles. He advocated traditional family values, Christian ethics, and temperance while denouncing behavior he considered inappropriate. A German immigrant who wrestled with the English language, Von der Ahe was a staunch Democrat and a saloon keeper intent on entertaining his customers. The Browns’ impresario was well suited for a population entranced by P.T. Barnum. Trumpeting a flamboyant personality, von der Ahe’s trademark promotions included flashy pregame parades and postgame shows. Several weeks before challenging Spalding, von der Ahe had hired Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show to entertain patrons following two games with Cincinnati. And of course there was the beer garden in right field and tolerance for a bit of rowdyism in the stands. To Spalding such shallow diversions and untoward behavior were beneath the respectability that baseball ought to embody.

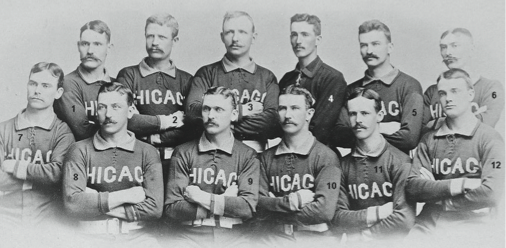

Spalding felt certain his team could easily dispatch von der Ahe’s club and once again embarrass the upstart league. In 1885 most regarded the National League as far superior to the American Association; therefore the league champion White Stockings were considered the best team in baseball. Led by Adrian “Cap” Anson, Chicago had an even better year than the Browns, winning 87 games while losing only 25. George Gore’s .313 and Anson’s .310 topped a team batting average that was almost twenty points higher than the Browns. The White Stockings also hit more than three times as many home runs as their rivals. The only Brown to lead his league in any offensive category was shortstop Bill Gleason, who was hit by more pitches than anyone else.13

In the pitcher’s box, the Browns’ two hurlers, Bob Caruthers and Dave Foutz, combined for 73 wins, ranking first and third in their league.14 But Chicago’s two regular pitchers did even better: Ace John Clarkson won an incredible 53 games and had an earned run average .22 runs lower than Caruthers. The other regular White Stockings pitcher, Jim McCormick, had a lower earned run average than did Foutz, and though he had won thirteen fewer games than Foutz, he had started twenty-two fewer. The White Stockings lineup also featured the player many considered to be the best in baseball, Mike “King” Kelly, along with several other acknowledged stars.

The one clear advantage St. Louis had was its fielding. Comiskey demanded excellence in the field and his 1885 Browns boasted what was arguably the best fielding team that had ever been assembled. Meanwhile, three Chicago infielders, first baseman Anson, second baseman Fred Pfeffer, and shortstop Tom Burns, led the National League in errors at their positions. Third baseman Ned Williamson was second at his position.15

The two owners hastily arranged a twelve-game barnstorming series that would open with a game in Chicago’s impressive new Congress Street Grounds followed by three in Sportsman’s Park.16 The final eight games were scheduled to be played in five other American Association cities.17 Adding spice to the contests, von der Ahe and Spalding each put up $500 that would go to the winning team. It was also agreed that the teams would split all gate receipts.

Little did either owner expect what was about to follow.18 Rather than contests between the best two teams in baseball, the games were characterized by controversial umpiring, sloppy play, and increasingly disgruntled fans.

The series opened in Chicago with several pregame challenges, including a ball throwing contest and a foot race around the bases.19 In the game that followed, the Browns built a 5–1 lead through seven innings, but in the eighth Chicago scored four times, the last three on a home run by second baseman Fred Pfeffer, to tie the game. Because of the delayed start, by the time Pfeffer crossed the plate twilight had descended. Between innings, umpire David Sullivan—who had been hired to officiate the series after umpiring 69 National League games that season—decided it was too dark to continue play and ended the game in a 5–5 tie.

The next afternoon a disappointingly small crowd of only 3,000 St. Louis fans (known as “cranks” in the late nineteenth century) filed into Sportsman’s Park for the second game.20 A notable figure who was not in attendance was Chicago’s leading hitter and star center fielder, George Gore. After the first game, team captain Anson was so upset with Gore’s “indifferent playing and indulging too freely in stimulants” that he told Gore to stay in Chicago.21 Meanwhile there were rumors that “[Gore] has been playing for his release.”22 Spalding denied the reports. Instead the team president contended that his center fielder was simply tired from a long season. After the series had concluded, Spalding implicitly referred to Gore, among other players, arguing that after winning the National League his club had been worn out and had not taken the Browns seriously.

Provoked by several controversial calls early in the second game, the home-town supporters raucously challenged umpire Sullivan. The complaints mounted to crisis proportions in the sixth inning. With a runner on third, White Stockings slugger “King” Kelly smacked a ball that shortstop Gleason bobbled before throwing to first. Sullivan, anticipating a close play at the plate, lost track of Kelly and called him safe at first when he was obviously out. Even the Chicago Tribune acknowledged that Kelly was out “by at least ten feet.”23 The St. Louis Post-Dispatch was more frank, labelling Sullivan’s call “…out-and-out robbery.”24 Upon hearing the call, Comiskey instantly charged Sullivan, launching a blistering rebuttal and ultimately threatening to pull his club off the field. After fifteen stormy minutes during which Sullivan reversed his call several times, play was resumed with Kelly on first. Amid continuing hoots and hollers, Kelly immediately stole second, and a pitch later scored the tying run on a single by Anson.

Two batters later, the go-ahead run scored on yet another disputed call. With Fred Pfeffer on third, Ned Williamson chopped a pitch down the first-base line. Initially the ball landed in foul territory but then spun back onto the playing field. Though he thought it had been called foul by Sullivan, Browns first baseman Comiskey picked the ball up and casually tossed it to his second baseman who was covering first. However, Williamson had hustled down the line and beaten Comiskey’s throw. Sullivan called him safe. Angrily confronted by Comiskey, Sullivan reversed his call and ruled it foul after all. With that Anson, Kelly, and several of their teammates jumped off the bench to confront the umpire. Intimidated by the charge, Sullivan again changed his decision. With that, a couple hundred Browns’ partisans, enraged by the second reversal, surged onto the field and headed for Sullivan.25

Fortunately for Sullivan, amid the swirl of protests security officers interceded and whisked the beleaguered umpire away. Later—from the safety of his hotel room—Sullivan declared the game a Browns’ forfeit because Comiskey had pulled his team from the field. Whether the Browns were pulled from the field or instead left at the same time as the White Stockings, Sullivan’s decision became the source of a heated debate throughout the remaining games of the series.26

When the two teams met again the next day, umpire Sullivan was gone. Instead Harry McCaffrey, who had played for the Browns in 1882, took over the umpiring duties. This time the game was played with little controversy. In front of another disappointingly small crowd of only 3,000, the White Stockings immediately “went to pieces in the field” flubbing away the game in the first inning when a two-out error led to five unearned St. Louis runs.27 From there on, the two pitching aces, Caruthers and Clarkson, dominated, with Caruthers and his teammates eventually prevailing, 7–4.

The last game scheduled for St. Louis included a new storm of protests. Before the first pitch Anson demanded that McCaffrey be replaced by an umpire with no ties to the Browns. After some discussion, Anson relented, but by that time the sting of his criticism had offended McCaffrey so thoroughly that he refused to officiate. After a 45-minute search, a local sportsman, William Medart—who apparently met Anson’s standards—was plucked from the stands to call the game.

It didn’t take long before the White Stockings’ manager regretted upsetting the apple cart. From the beginning every close call reflected the new umpire’s avid support for his hometown team. In the fifth, a Medart mistake cost Chicago a run. Even the St. Louis papers acknowledged Medart’s bias.28 Despite it all, the White Stockings were only down, 3–2, as they batted in the ninth. With one out and Tommy Burns on first, Chicago pitcher Jim McCormick lifted a pop fly to shallow right field that Comiskey dropped. Picking the ball up, the Browns’ first baseman dashed over and tagged McCormick who had rounded the bag but was clearly back on first. Nevertheless, Medart called the runner out. Enraged, McCormick rushed the umpire. Fortunately Anson was able to block his path. At the same time, future evangelist Billy Sunday leaped up off the Chicago bench with fists clenched and charged toward the umpire. Reacting quickly, Mike “King” Kelly, not usually known as a peacemaker, grabbed his teammate just short of Medart. Once order was finally restored, the game ended on a pop foul.

During the scheduled four-day hiatus that followed, the umpiring controversy was resolved. John O. “Honest John” Kelly was hired to officiate the remaining games. Kelly combined experience in both leagues with an impeccable reputation and, most importantly, the respect of both Spalding and von der Ahe. Unfortunately the resolution did nothing to enhance the competition. The trip to Pittsburgh generated little interest among locals. Additionally, the fifth game was played on an exceptionally cold mid-autumn afternoon. Consequently only 500 paid to watch the contest. Rather than the hard-nosed play that had characterized the first four games, onlookers watched two sloppy teams lumber through the afternoon, during which Anson’s crew methodically pecked their way to a 9–2 victory.

Circumstances did not improve during the following two days in Cincinnati. Like their Pittsburgh counterparts, local Red Stockings fans showed little interest in games between the Browns and the White Stockings. The Cincinnati Enquirer described game six as “one of the bummest games seen here this season.”29 The two teams committed a total of 17 errors, half of which “were what are known in base-ball parlance as ‘rotten.’”30 Aside from another 9–2 win, the afternoon’s saving grace for the White Stockings was Jim McCormick’s two-hit pitching.

Amidst sagging attendance and players anxious to move on to postseason endeavors, the two owners agreed that the second game in Cincinnati would be the last game in the series.32 However, whether game two should be counted as a St. Louis forfeit remained an unresolved issue. If it counted, Chicago was up, 3–2. If not, the series was tied. In either case some—like the St. Louis Post-Dispatch—lamented that without additional games “the question as to which club is superior [remains] entirely in the dark.”33 Despite the concerns, the two team captains, Comiskey and Anson, came to an agreement. Chicago’s leader, confident after two relatively easy victories, comfortable with the current umpire, and eager to boost attendance, agreed to drop the disputed game. The winner of the last game would be recognized as the winner of the series.34 Anson would regret this decision.35

The final game started well for the White Stockings, but the team fell apart quickly. Up two runs after an inning, Chicago’s defensive woes reemerged in the third. Four hits, two errors, and a passed ball that allowed two runners to score, led to four St. Louis tallies. At that point the “slaughter” was on. Errors, misplays, and poor pitching marked the rest of the afternoon for Anson’s crew. Six more Browns runs in the fifth put the game out of reach. The Cincinnati Enquirer called it “one of the worst games ever played in Cincinnati…yesterday’s exhibition, on the part of the Windy City men, was simply disgusting.”36 In the end St. Louis came away with a 13–4 rout and a claim to being the world’s best baseball team.

As expected, a very unhappy Albert Spalding wasted no time in snubbing the claim. The following day he explained to Chicago Tribune readers that “[it] is widely contended that the series just finished has been contested to decide the championship of the world. That is nonsense.”37 He stressed that the forfeited game should be considered a Chicago win and, therefore, the series ended with each team having won three games. Spalding insisted that he would never have agreed to play games in American Association cities using American Association rules and umpires had he considered it a world championship. Instead the games had simply been postseason exhibitions as in the previous year. Additionally, his players, who he acknowledged did not play well, didn’t care about the games because they recognized that as a result of the poor attendance they were not going to receive much compensation for their efforts. Instead Spalding blamed “the enterprise of the newspapers” for promoting the games as a world championship.38

Spalding’s opinions were quickly echoed by several sources. In addition to The Chicago Mirror—which was acknowledged to be Spalding’s media “organ”—Sporting Life, a weekly paper published in Philadelphia, seemed to share Spalding’s assessment. However, several of the Sporting Life reports, filed under the pseudonym “Remlap,” were submitted by Harry Palmer, who covered baseball for the Chicago Tribune and was quite sympathetic to his hometown team. At the beginning of the series, the weekly described the games as merely a postseason exhibition between two champions. The paper argued that “the greatest difficulty usually is that it is hard to awaken enough interest on the part of the [National] League players to do their best” when playing games after the championship season.39 Throughout the series, Sporting Life continued to downplay the games while at the same time acknowledging that “the Browns are without a doubt a very smooth organization and can play with the best of them. Had they been in the League instead of the American Association…[they] would quite likely have ranked other than last in the race.”40

Immediately after the series, the paper concurred with Spalding. In rhetoric clearly influenced by Spalding, Sporting Life listed the various reasons that St. Louis should not be considered world champions. The paper’s conclusion was: “The St. Louis men were bound to win by hook or by crook for the glory of beating the League champions and the local umpires were bound to help them.”41 A week later, under a column titled “The World’s Championship,” the weekly modified its view a bit, reporting that “the Chicago Club is much chagrined…[about] the loss the ‘world’s championship,’ a title which amounts to little…”42 However, in the end Sporting Life came down solidly on Spalding’s side. In a final assessment, the weekly concluded that “Spalding is right…that Chicago is entitled to the so called drawn game in St. Louis [and] the series as originally arranged was not completed.”43

Other papers were not as eager to embrace the Spalding defense. Even the Chicago Tribune introduced its account of the final game by announcing: “Chicago Badly Beaten By The St. Louis Browns—The Latter Now Champions Of The World.”44 The following day, beneath Spalding’s defense, the paper reprinted an article from the Cincinnati Commercial-Gazette which defended the Browns’ right “to lay claim to the championship of the world.”45

Not surprisingly, the St. Louis papers also described the Browns as world champions. The Missouri Republican agreed with the St. Louis Globe-Democrat announcement that “the game to-day…was the decisive one in the series between these two clubs for the championship of the world, and resulted in an easy victory for the St. Louis team.”46 Another to side with the Browns was the 1886 edition of Reach’s Official American Association Baseball Guide, which cites umpire Kelly’s pre-game announcement that the two managers had agreed that the winner of the seventh game would be considered the winner of the series.47

A fitting assessment of the series came from Henry Chadwick. The most influential baseball writer of an earlier era, Chadwick was still a voice to be considered. Writing in the New York Clipper, he commented that “as it stands the St. Louis Club team are unquestionably the champion team of the United States for 1885 and nothing can prevent them from legally claiming the honor.”48 He also proposed that a championship series between the champions of the American Association and the National League ought to be made a regular closing series.

A month after the final out, Sporting Life returned to both Spalding and von der Ahe the $500 prize money that each had promised to the series winner. Maintaining that the second game had been forfeited and therefore the series ended in a 3–3 tie, the weekly announced “The championship of the United States remains in abeyance.”49 By accepting the return, von der Ahe was, in effect, acknowledging that his team could not conclusively claim victory. Instead he began preparing for the 1886 season, which he hoped would include another clash with the National League champions and an undisputed world championship.

Whether the Browns won the series or it ended in a draw remains unresolved even today. Most sources agree with Albert Spalding that the series concluded in a three-game tie.50 Others hold to the argument that by winning the final game the Browns won the series.51 The real significance of that 1885 series, however, is not who won but rather that the series served as the second step toward instituting the tradition of a postseason world-championship series. Building upon the games played by the two league champions the previous year, the 1885 games further established guidelines toward the evolution of the World Series as it exists today.

A year later the same two teams again won their leagues and arranged another postseason series. This time, hoping to avoid some of the unresolved issues from the 1885 series, both teams agreed that the winner would be considered baseball’s world champion. Each year until after the 1891 season when the American Association folded, the two leagues continued to play an end of the season world championship series. Even after the demise of the American Association, the National League maintained the evolving tradition. Though the championship series was suspended during the early twentieth century while the National League wrestled with the new American League, the union of the two leagues in 1903 fostered the resumption of a world championship series which we continue to enjoy today as the pinnacle of baseball competition.

PAUL E. DOUTRICH is a professor of American History at York College of Pennsylvania where he teaches a popular course entitled “Baseball History.” He has written numerous scholarly articles and books about the revolutionary era in America and has curated several museum exhibits. For the past fifteen years his scholarship has focused on baseball history. He has contributed manuscripts to various SABR publications and is the author of “The Cardinals and the Yankees, 1926: A Classical Season and St. Louis in Seven.”

Notes

- There are several sources that include a discussion of the 1885 series. The most thorough account can be found in Jon David Cash, Before They Were Cardinals (University of Missouri Press: Columbia, MO., 2011); Jerry Lansche, Glory Fades Away: The Nineteenth-Century World Series Rediscovered (Taylor Publishing: Dallas TX, 1991) provides a succinct game-by-game account of the series. David Nemec, The Beer and Whiskey League (Lyons Press: Guilford, CT, 2004) also offers a concise description of the series.

- One of the questions about the series was what to call it. Variations of “the Baseball Championship of the United States” or “the World Baseball Championship Series” were used, often in the same article.

- There are several good biographical accounts of Chris von der Ahe. The most thorough is J. Thomas Hetrick, Chris Von der Ahe and the St. Louis Browns (The Scarecrow Press: Latham Maryland, 1999). A concise and very informative article was written by Richard Egenreither’s “Chris Von der Ahe: Baseball’s Pioneering Huckster” (Baseball Research Journal, Volume 18, 1989).

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January, 15, 1884: 5. By 1884 the number of stockholders had been reduced to about twenty. At the time other notable investors who formed the Sportsman’s Park Club and Association in addition to von der Ahe were newspaper writer Al Spink, fellow saloonkeeper John Peckington, brewer William F. Nolker, and Congressman John J. O’Neill.

- Hetrick, page 6; Cash, page 59. The bartender was Ned Cuthbert, who began his professional baseball career with the Athletics of Philadelphia in 1871. By 1881 he had played for several professional teams.

- Nemec provides a detailed description of the negotiations involved in organizing the American Association.

- The other five charter members of the American Association were Baltimore, Cincinnati, Eclipse, Athletics, and Alleghenys.

- Two of the twelve teams—Virginia and Washington—did not play enough games to be eligible for the league championship.

- Comiskey made it clear: “I go on the field to win a game of ball by hook or crook.” Quoted in J. Thomas Hetrick, Chris von der Ahe and the St. Louis Browns, 40.

- Hugh Weir, “The Real Comiskey,” Baseball Magazine, February, 1914: 24.

- Baseball Almanac provides a game-by-game win-loss account of the Browns season. (See http://www.baseballalmanac.com/teamstats/schedule.php?y=1885&t=SL4, accessed on June 28, 2017.)

- There are several good biographical descriptions of Albert G. Spalding, the best of which is Peter Levine’s monograph: A.G. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball: The Promise of an American Sport (Oxford University Press: New York, 1985). Bill McMahon has written Spalding’s entry in the SABR BioProject. There is also biographical information provided in Harold and Dorothy Seymour’s Baseball: The Early Years (Oxford University Press: New York, 1960)

- Baseball-Reference.com. See https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/AA/1885-batting-leaders.shtml accessed on June 28, 2017.

- Nemec, Beer and Whiskey, 107.

- Baseball-Reference.com. See https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/AA/1885-fielding-leaders.shtml accessed on June 28, 2017.

- The park, later called West Side Park, was located at the western end on a small block bounded by Congress, Loomis, Harrison, and Throop Streets. The elongated shape of the block lent a decidedly bathtub-like shape to the park, with foul lines reportedly as short as 216 feet. Capacity was roughly 10,000 spectators. A bicycle track encircled the baseball field at the height of the contemporary bicycle craze.

- Games were scheduled in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Baltimore, Philadelphia and Brooklyn.

- The Sporting Life, October 21, 1885, 3.

- The Inter Ocean, October 15, 1885, 5. Ned Williamson won the ball throw and his teammate, second baseman Fred Pfeffer, won the foot race.

- Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1885, 2; Lansche, 67.

- Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1885, 2.

- Sporting Life, October 21, 1885, 1.

- Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1885. 2.

- St. Louis Post Dispatch, October 16, 1885, 8.

- Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1885. The Tribune reported that 200 fans came onto the playing field.

- Lansche, 61–63; Cash, 111-113; Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1885. The Tribune incorrectly reported that Billy Sunday rather than Fred Pfeffer scored the go-ahead fifth White Stockings run.

- Chicago Tribune, October 17, 1885, 2.

- Missouri Republican, October 18, 1885; Sporting Life, October 28, 1885. A National League official who witnessed these games (in St. Louis) said they were simply robberies. “The St. Louis men were bound to win by hook or by crook for the glory of beating the League champions, and the local umpires were bound to help them.”

- Cincinnati Enquirer, October 24, 1885, 2.

- Ibid.

- Local correspondents in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati wired game accounts to newspapers in St. Louis and Chicago. The accounts in those papers were therefore very similar.

- Chicago Tribune, October 23, 1885, 2.

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 24, 1885, 9.

- Chicago Tribune, October 26, 1885, 2. The Tribune published a copy of an article in Cincinnati’s Commercial-Gazette in which Cap Anson is quoted as having agreed that the winner of the final game would be the world’s champion. However, above the reprint is a statement from Albert Spalding declaring the series a 3–3 tie.

- Cincinnati Enquirer, October 25, 1885, 10; Chicago Tribune, October 25, 1885, 11.

- Cincinnati Enquirer, October 25, 1885, 10.

- Chicago Tribune, October 26, 1885, 2.

- Ibid.

- Sporting Life, October 14, 1885, 5. Palmer signed his pieces “Remlap” which is Palmer spelled backwards.

- Sporting Life, October 21, 1885, 1. “Remlap” is the author.

- Sporting Life, October 28, 1885, 4. “Remlap” is the author.

- Sporting Life, November 4, 1885, 1.

- Sporting Life, November 18, 1885, 3.

- Chicago Daily Tribune, October 25, 1885, 11.

- Chicago Daily Tribune, October 26, 1885, 2.

- Missouri Republican October 25, 1885; St. Louis Globe Democrat, October 25, 1885.

- Reach’s Official American Association Baseball Guide: 1886, 11–12.

- New York Clipper, November 7, 1885, 9.

- Sporting Life, November 25, 1885, 4.

- Cash, 122.

- John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden (Simon and Schuster: New York, 2011) 202-03; Lansche, 66.