Christo Von Buffalo: Was He the First Baseball Cartoonist?

This article was written by Joseph Overfield

This article was published in 1981 Baseball Research Journal

When Albert G. Spalding wrote his American National Game in 1911, he hired the well-known cartoonist, Homer C. Davenport, to provide appropriate works of art, and in the front of the book he thanked Mr. Davenport, “to whose genius much of the interest in this volume is due.”

Theodore A. Dorgan, who used the nom de plume “Tad” as his signature, was the best-known baseball cartoonist of the early part of this century. It was he, according to Lee Allen, who first called a frankfurter on a roll a hot dog. Probably the most famous of all baseball cartoonists was the late Willard Mullin who plied his trade for the New York World-Telegramand The Sporting News. His rendition of the Brooklyn Bum, with his torn pants, battered hat and shoes, made the Brooklyn Dodgers famous and recognizable far beyond the confines of America’s sports pages. Burns Jenkins of the long-departed New York Journal American, Murray Olderman of the Newspaper Enterprise Alliance, Bill Gallo of the New York Daily News, and Gene Mack of the Boston Globe are others who gained national reputations with their baseball cartoons.

Not nationally known at all was Christopher Smith who drew topical baseball cartoons in Buffalo in 1877; but he could well have been the very first of his breed. In his adopted city (he had been born Christoff Schmidt in Germany in 1841), he was known as Christo Von Buffalo. As Theodore A. Dorgan was to do a few generations later, he used a shorter signature on all of his cartoons, signing each one, “Christo,” with the tail of the “C” forming a flourish under the rest of the signature.

The Buffalo club of 1877, the city’s first professional nine, was neither an artistic (apart from Christo) nor a financial success. Formed in mid-season, the team was by necessity made up of callow youths, castoffs and ne’er-do-wells. It played a 40-game schedule against National League and International Association clubs, winning ten games, losing 27 and tying three. At season’s end on October 26, its books showed a cash balance of just $490.19, plus 47 bats and three baseballs. It was explained that the supply of baseballs would have been greater had it not been for the practice of the time which dictated that the losing team give a ball to the winning team. Gate receipts totaled $4324.19, out of which came such expenses as $3833.59 for salaries, $85.42 for bats and $25 paid to Mark Stinson, who had been injured when the bleachers collapsed during a game against Louisville.

The Buffalos were managed by a triumvirate of local businessmen: Edward R. Spaulding, assistant cashier of the Farmers and Mechanics National Bank and son of Elbridge Spaulding, long-time congressman and well-known as “Father of the Greenback;” Elihu Spencer, agent for Equitable Life, and John Van Velsor, Proprietor of a Main Street bakery. For neophytes, their accomplishments were quite remarkable. First of all, they signed a 17-year-old phenom named Larry Corcoran, who had been pitching for the Livingstons of Geneseo, N.Y., and then at the end of the season, after they had re-signed him at $600 for 1878, changed their minds and bought up his contract for $50, simply because they had no catcher who could hold him.

By such a small event as this was the course of baseball history changed. Corcoran went on to become one of the solid pitchers of the game’s early years (1880-87) and hurled three no-hitters, while Jim Galvin, signed in his place, was destined to become the greatest pitcher in Buffalo baseball history and a Hall of Famer.

The Buffalo management also had the perspicacity to sign another 17-year old with great potential but did not have the patience to hold on to him. John Montgomery Ward joined the team in September 1877 but was not resigned for 1878 because of his extreme youth. Among others who played for this pioneer Buffalo nine were Jim (Chief) Roseman, who was to play ten years of major league ball, and Andy Cummings, a gypsy ballplayer whose sad story was epitomized by a dispatch out of Covington, Ky., dated January 6, 1889: “Andy Cummings, the once noted player, has been sentenced to the Kentucky Penitentiary for chicken stealing. Whiskey is to blame.”

The men who operated the Buffalo club were imaginative, to say the least. They offered reduced prices for ladies. They maintained a ticket office in a downtown music store and permitted an injured player to sell scorecards at the ballgame. These scorecards, which sold for a nickel, contained ads for local merchants as well as the lineups for the competing teams. The Buffalo club also hired an official scorer who meticulously recorded every pitch of every game. The printed score sheets he used (the writer has three of them in his possession) recorded 23 different elements of the game, ten under batting, six under fielding and seven under errors, plus a tabulation of called balls and called strikes by both teams. In modern scoring, each position has a number. The Buffalo scorer accomplished the same thing by using letters — “A” for first base, “B” for second base, “D” for third base, etc.

So that Buffalo fans could keep close tabs on the games, a large scoreboard was set up on the field. It was Christopher Smith’s job to record the-inning-by-inning results. But Smith, who with his brothers Gus and George, ran a sign and paint shop on Sixth Street, about a mile from the Niagara St. park where the Buffalos played, had talent far beyond the ability to print nice neat ciphers on the scoreboard. He used this talent to draw on poster paper a topical cartoon, giving his pictorial view of the high or low spots of the game. After each cartoon was completed, it was taken to Joseph Garson’s clothing store in downtown Buffalo, where it was displayed in the window for all to see.

How many cartoons Smith drew is not known, but 34 of the originals are still in the possession of the family of Dr. William Smith of Hamilton, Ohio, a nephew of the artist. It was the privilege of this writer to see the entire collection and to make copies of the more interesting ones.

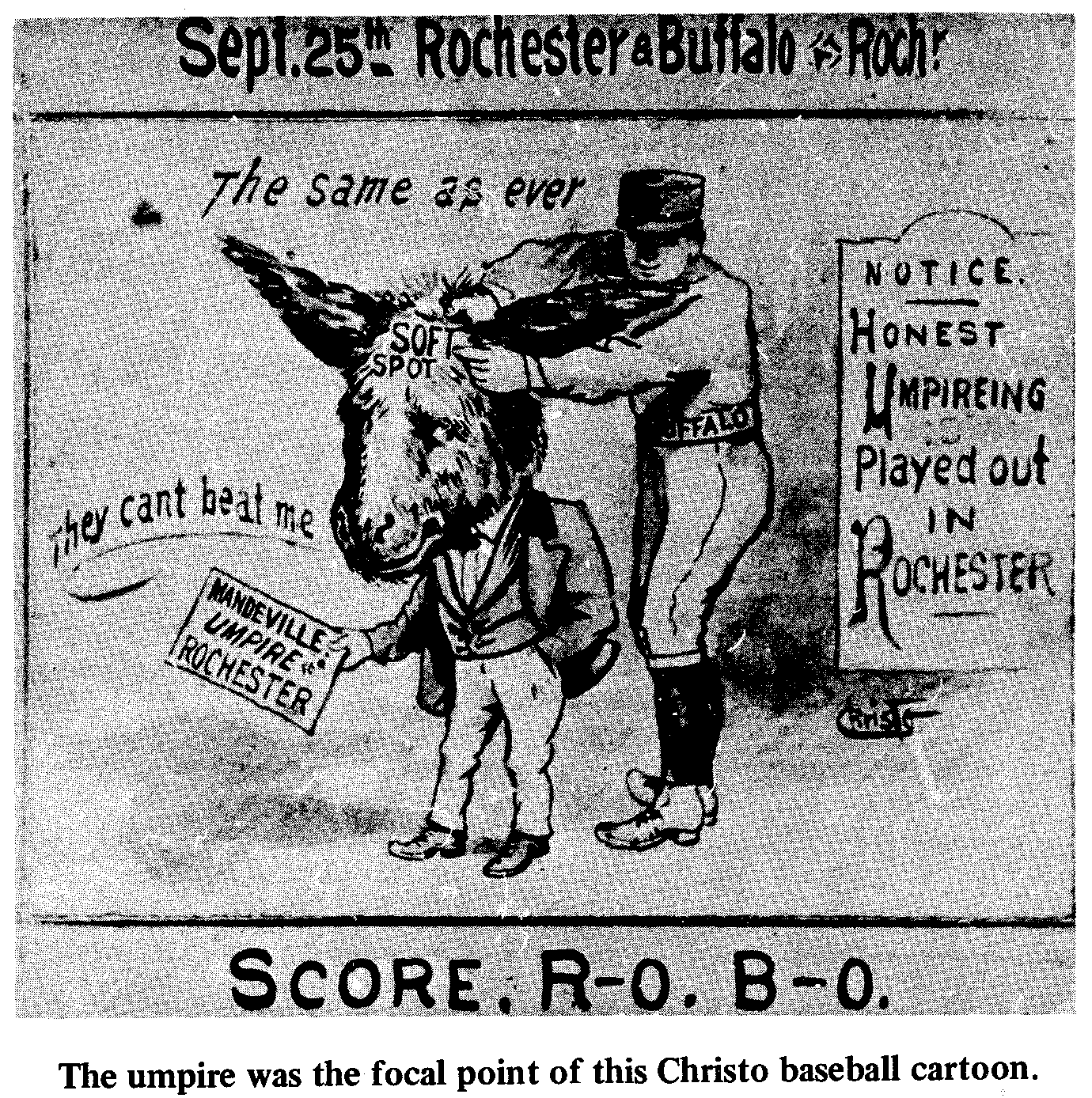

Christo’s cartoons are well composed and their captions are typical of the gentle but sometimes biting humor of this form of art. After a game in Rochester, which had been marked by several bitter disputes with the umpire, Christo depicted umpire Mandeville with the head of a jackass, between whose huge ears was lettered “soft spot.” His caption read, “Honest umpiring (sic) played out in Rochester.”

His cartoon following the September 28 game against the Alleghanys of Pittsburgh (final score, Alleghany 7, Buffalo 2) is done with a background of belching smokestacks and is captioned: “They say Pittsburgh looks like hell with the lid knocked off. That accounts for the Alleghany boys playing so like the devil.” Central to the cartoon is a fallen bison, getting a shot of “strengthening bitters” from a bat held by a Buffalo player.

After a September game with Indianapolis, which the visitors won, 7-0, Christo’s cartoon is composed of the scoreboard with the artist adding the ninth goose egg to the Buffalo line score. “If practice makes perfect, our scorer has the lower line down fine,” reads the caption.

After the last game of the season on October 16, a 3-0 loss to bitter rival Rochester, Christo showed his anger and disappointment by stuffing all the Buffalo players into a huge traveling bag, labeled, “The remains of a sorrowful baseball club.” Waiting in the wings is a railroad car ready to transport them to “all parts of the United States. Across the bottom of this cartoon is the further admonition: “An owner wanted. Buffalo please don’t apply.” Signed “Christo.”

It is unlikely that Christo continued his baseball cartooning after the 1877 season. At least that is the conclusion that one must come to after an extensive search of old Buffalo newspaper files.

But the fact remains that in 1877 he drew at least 34 topical baseball cartoons, and unless subsequent research unearths someone who did it earlier, then we must consider Christopher Smith the first to practice an art that was for so many years a daily feature of America’s sports pages.