Cigars, Horses, and a Couple of Homers: Babe Ruth’s Experience in Cuba

This article was written by Bill Nowlin - Reynaldo Cruz Díaz

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

Havana served for many years as something of a playground for the idle wealthy of the United States, as often as not those of New York, particularly during the Prohibition years (1920-1933), when alcohol was banned in by an amendment to the US Constitution. It was a major tourist mecca and attracted a large number of American entertainers, gamblers, gangsters, and businessmen prepared to exploit the Cuban citizenry and make as much money as they could.

That very first year of Prohibition – the 18th Amendment was ratified in January 1919 and went into effect one year later – Babe Ruth was in his first year at a member of the Yankees, and he hit a previously unfathomable 54 home runs (more than any other entire team in the major leagues save the Phillies, who hit 64 as a team.)1

As motion-picture newsreels became a widely available form of entertainment and information, Ruth and many other figures in sports, from baseball to boxing, and in other realms from music to the movies, were becoming true national celebrities. John McGraw’s New York Giants had already been booked to play a number of postseason exhibition games in Cuba. But “[w]ith money to spare and ambitions that knew no limits, Cuban impresarios wanted to cash in on the new phenomenon and invited the Babe to display his talents as a Giant at Almendares Park.”2

Cuba was at the time living in a period known as the “Vacas Gordas” (Fat Cows), mainly helped by the postwar boom reached with the sale of sugar, highly priced worldwide. This enabled Cuban entrepreneur Abel Linares to hire the slugger so that he could play nine games with the New York Giants, offering him an almost staggering 2,000 US dollars per game.3 His salary for the full 1920 season is believed to have been $20,000. At the time, the Cuban peso and the US dollar had an exchange rate of one-for-one.

The Bambino’s exploits were very well known in Cuba already, and his presence in the games (most of them to be played in the new Moderno Almendares Park) would definitely draw a lot of fans to the game, even though they would mostly be cheering against him and the Giants.4

It wasn’t just coincidence that the Giants of the day often played preseason games in Havana. John McGraw owned the Oriental Racetrack there, in partnership with team owner Horace Stoneham. He’d first visited the island when it was still a Spanish colony, in 1890. The Oriental Racetrack property also embraced a restaurant, a small hotel called the Cuban American Jockey Club, and a casino.5 The property was acquired during October 1919, the very month that gambling interests corrupted a number of the Chicago White Sox into throwing the 1919 World Series.

Ruth reportedly lost most of the money he was paid while “gambling at jai alai and other games.”6

The Giants departed by train from New York’s Penn Station on October 12 and arrived in Havana by ship from Key West on October 15, staying at the Hotel Plaza, just in time to play the “American Series” from October 16 through November 28.

Ruth himself didn’t arrive until October 29, in time to play the ninth game in the series the following day. He came with his first wife, Helen, and they also stayed at the Hotel Plaza, across from Parque Central in Havana, at the corner of Zulueta and Neptuno. Nearly 100 years later, the Plaza still serves as a hotel and has a plaque outside of the room where the Ruths stayed. The Babe also visited the famous Sloppy Joe’s Bar, opened in 1917, a block away from the hotel – the bar holds pictures of the famous people who have visited it, including Hall of Famer Ted Williams.

The costs of travel and accommodations for the Ruths were covered by Linares. The fee paid to Ruth to play was reportedly more than all of his teammates combined.7

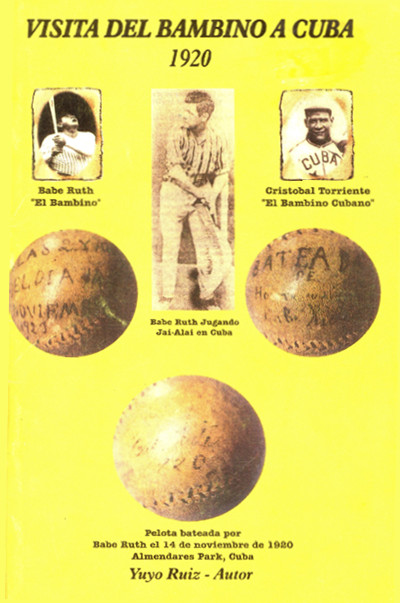

Bilingual pamphlet “The Bambino Visits Cuba 1920” by Yuyo Ruiz. (Courtesy of Jane Leavy.)

Ruth’s first game was on October 30. Research done by Cuban researcher and historian Jose Antonio “Tony” Perez in the pages of the Havana newspaper El Mundo indicates that Ruth played center field and doubled and tripled in the game, won by the Giants over Habana, 4-3. The losing pitcher was Oscar Tuero; both Jose Acosta and Lefty Stewart worked in relief. The winning pitcher was Pol Perritt.

Ruth’s second game saw Rosy Ryan of the Giants shut out Almendares, 3-0, on October 31. Ruth singled and tripled off Emilio Palmero. In the sixth inning, Palmero struck out the Babe on three consecutive fastballs. When he got back to the bench, a very impressed Ruth reportedly proclaimed, “Where did the Cubans find that guy? He could pitch for any team.”8

After two days off – Ruth was reportedly engaged with Havana’s nightlife – Moderno Almendares Park witnessed the Giants’ third victory, when Perritt again subdued Habana on November 3, holding them to one run and five hits, while Acosta and Tuero surrendered seven runs and nine hits; Acosta bore the loss.) Each team made two errors, and it happened to be Ruth’s worst day at the plate; he was struck out by Acosta in all three at-bats, although he got on base a fourth time and scored one run.

On November 4 it was Almendares again. The Giants prevailed in a slugfest, 10-8. Each team had 14 hits and made three errors. Ryan got the win and Palmero bore the loss. Ruth was 2-for-3 at the plate, with a single and a double, and also pitched an uneventful inning.

The November 6 game was a remarkable one. Ruth played first base and again pitched briefly. He was 0-for-3. The real story, though, was provided by another Hall of Famer. “Cuban slugger Cristobal Torriente had stolen [Ruth’s] thunder by clouting three mammoth round-trippers in a memorable afternoon” – one of the homers reportedly hit off Babe Ruth, who pitched briefly in that game.9 Torriente was voted into Cooperstown in 2006. The summary of his career on the Hall of Fame website begins: “‘The Black Babe Ruth’ was the nickname Torriente acquired in the fall of 1920. … Torriente outhit and out-homered Ruth in the series.”10

Torriente later played several years for the Chicago American Giants (and a final season with the Detroit Stars) of the Negro National League. After the November 6 game, he was presented with 400 cigars, a gold watch, and 103 pesos in cash collected on the field during the day.

The Havana newspaper El Día presciently reported, “Yesterday, Cristobal Torriente elevated himself to the greatest heights of glory and popularity. His hitting will enter Cuban baseball history as one of its most brilliant pages.”

Gonzalez Echevarria’s account was more sanguine than Figueredo’s. The score was indisputably 11-4 in Almendares’ favor, but he readily confesses, “I was genuinely sad to discover that the facts did not quite square with the myth.” As he reports, “The story goes that on this day Torriente outdueled Ruth by blasting three home runs, while the American idol could only muster one. The facts are as follows: Babe Ruth did not get a hit that day, and while Torriente got three homers and a double, the homers were against Highpockets Kelly, the Giant first baseman, who had pitched one game in relief three seasons earlier. The double was against the Babe himself, who had taken the mound for an inning as a stunt. … The inescapable truth is that Torriente’s feat was accomplished against a first baseman and a former pitcher and in a kind of holiday spirit – almost a carnival atmosphere. Furthermore, it is not clear from contemporary accounts if Torriente’s homers actually went over the far-flung fences of Almendares Park. All three went to left or left-center, where the dimensions [are] each six hundred feet, but the only thing the newspaper story says is that the balls went over the fielders’ head.”11 Some of the Giants, according to Diario de la Marina sportswriter Ramon S. Mendoza, were descompuestos (politely suggesting they appeared to be hung over thanks to excess alcohol consumption.) Catcher Earl Smith, for instance, had four passed balls in the game.

Peter Bjarkman endorses this conclusion, in effect underscoring the same research: “A local press account cited by González Echevarría suggests that Giants pitchers were not taking most of the games on the tour very seriously, were in truth lobbing ‘batting practice tosses’ at the Almendares hitters, and were at any rate probably on the day of Torriente’s heroics still feeling the effects of excessive partying the previous night.”12

Much of the partying was undoubtedly done at McGraw’s casino. Of the “American Series,” Charles Alexander wrote, “For once McGraw didn’t seem to take baseball seriously. The major-leaguers won most of the time, lost a few, and had plenty of fun at McGraw’s and Stoneham’s racetrack and casino. Playing before big crowds, the ballplayers did well financially, most of all Ruth. At least until the croupiers and assorted con artists got through with him, by which time he had little left of the $20,000 or so he’d gained from the trip.”13 One contemporary report, a lengthy summary in The Sporting News, said Ruth had lost $35,000 at the race track and that “the Cubans also stung him hard in a big crap game, and he returned to the States solely because he was broke.”14

The next day, on November 7, Ruth was 2-for-3 – both hits were singles – against Stewart of Habana. Ruth was back in center field, where he played for the remainder of the games.

His first home run came during a 6-5 loss to Almendares on November 8, an inside-the-park home run. He was “safe at the plate by inches.”15

Gonzalez Echeverria says that Diario de la Marina’s Mendoza reported the ball “went to the corner between the end of ‘sol’ and the center-field wall or scoreboard” and “may well have been the longest homer ever hit at Almendares Park; a rough estimate would be about 550 feet.”16

There were then three days off. On November 12 the two teams played to a 3-3, eight-inning tie game, which was called due to darkness. Ruth was 0-for-4.

On the 14th the Babe collected his second home run, against Almendares in a 7-3 Giants win. He was 1-for-2. This one perhaps cleared the fence; Tony Perez, historian Dr. Oscar Fernandez, and longtime SABR member Ismael Sene have all told Reynaldo Cruz that one of Ruth’s homers cleared the fence and it was the only homer to clear the fence in the whole series.

New York was outmatched by Adolfo Luque’s Almendares team but beat Habana handily. Seventeen games in all were played, with New York posting records vs. Almendares of 2-4 (with three ties), and vs. Habana of 6-1 (with one tie.) There was one game played against an All-Cubans team, which ended in a 2-2 tie.17

The contingent moved to Santiago de Cuba, where Juan Lageyre paid the Bambino $3,000 for two games in Cuba Park of the eastern city. However, most of the Giants team sat out the game, and The Sultan of Swat made up a “Babe Ruth” team with Rosy Ryan and himself, along with a group of Cubans. They were whitewashed, 4-0, by Pablo Guillen (a pitcher who never played professionally and had a slow ball) and the Santiago team, which scored all of its runs in the third inning. Playing first base, Ruth went 1-for-3. According to the local newspaper in Santiago, Guillen struck out Ruth three times in a row.18

His stay in Santiago de Cuba was not as rewarding as he had anticipated. He bet on the horses at Oriental Park, gambling at jai alai matches and in casinos as well, in the night and in the mornings as well. He lost all his money betting and returned to Havana with only 40 cents in his wallet.19

Linares himself was understood to have made $40,000 in profits on the tour and to have “elevated Cuban baseball…to a new prominence.”20

The New York Times summarized Ruth’s reception in Cuba: “They liked the Babe down there in the land of tobacco, sugar and skimmed milk. He was greeted with uproarious applause constantly, although his prowess as a slugger was seldom on display. He made only two of his far-famed circuit smashes in the whole series.”21

The Sporting News quoted Ruth as saying the fences in the Havana ballpark “are not made for home runs,” though noting that Torriente had hit three in one game. The paper wrote, “The Babe hit a lot of mighty drives but the fielders played in the next county for him and gathered the most of them in. Two homers were all he got in the ten games he played as a member of the Giants.” Ruth stayed on, having signed a new contract to play in 10 more games with a Cuban team.22

Ruth was less than politically correct when he declaimed on the ballparks in Cuba: “Oh, they’re punk. The fence is four blocks from home plate, and them greasers expect you to knock it over every time.” About the country in general, he said, “It’s a great place. … The kids used to chase me all over the island calling me Bobbie Ruth.” But he added, disparagingly, of Torriente in particular, “Them greasers are punk ball players. Only a few of them are any good. This guy they calls after me because he made a few homers is as black as a ton and a half of coal in a dark cellar. I guess I’ll go back to Cuba next winter.”23

The Washington Post reported that, despite just the two home runs, Ruth had hit for a .345 average, with three triples, three doubles, and two singles, and scored five runs. He struck out six times.24 Figures compiled by Jose Antonio Perez agree, crediting him with 11 RBIs, 11 walks, two stolen bases, and one sacrifice bunt.25

In late November, Ruth wrote to Miller Huggins from Havana that he hoped for an even better regular season in 1921 than he had enjoyed in 1920. He noted that he had missed a number of games in 1920 but that by playing winter ball in Cuba he would be in “perfect trim” and that, furthermore, he wasn’t going to mess with acting in motion pictures: “I am fully convinced that my batting eye was injured by the strong light of the movie studio, and I’m not going to let those fellows cheat me out of any more home runs.”26 However he may have prepared for the 1921 season, it paid off. He played in almost every game and hit 59 home runs.

Ruth visited Cuba only that one time to play baseball. Andres Pascual says he returned in 1921 to “engage in what would become a dangerous hobby for him: the horse races in Oriental Park.”27

REYNALDO CRUZ DIAZ is the founder and head editor of the Cuban-based magazine Universo Béisbol, which is hosted in MLBlogs. He is a language graduate of the University of Holguin, in his hometown, and has been leading the aforementioned magazine since March 2010. A SABR member since the summer of 2014, he writes, translates, and photographs baseball and was in the first row of the Barack Obama game in Havana, shooting from the Tampa Bay Rays dugout. In spite of the rich history of Cuban baseball, his favorite player happens to be no other than Ichiro Suzuki, whom he hopes to meet and interview. A retro-ballpark lover, he views Fenway Park, Wrigley Field, Koshien Stadium, and Estadio Palmar de Junco as the can’t-miss places in baseball.

BILL NOWLIN was elected as SABR’s Vice President in 2004 and re-elected for five more terms before stepping down in 2016, when he was elected as a Director. He has specialized in Red Sox research since he turned to writing and research in the late 1990s and has written, edited, or co-edited more than 75 books and more than 750 articles, many of which are Red Sox-related. He is one of three founders of Rounder Records, one of America’s most successful independent record labels. A member of the International Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame, he has also traveled widely, visiting more than 125 countries to date, and has occasionally taught courses at Boston-area universities on “Baseball and Politics” and Sportswriting. He was the 2011 winner of the Bob Davids Award, SABR’s highest honor. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to the memory of Peter C. Bjarkman.

Sources

Thanks to Tony Perez for compiling figures on the 1920 visit of the New York Giants – and Ruth – to Cuba. Thanks to Jane Leavy for loaning the pamphlet “The Bambino Visits Cuba.”

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the authors also consulted a number of biographies of Babe Ruth, including:

Creamer, Robert. Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992).

Leavy, Jane. The Big Fella (New York: HarperCollins, 2018).

Montville, Leigh. The Big Bam (New York: Doubleday, 2006).

Wehrle, Edmund F. Breaking Babe Ruth (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2018).

Notes

1 The 29 home runs he had hit for the Boston Red Sox in 1919 had already set the major-league record and Ruth’s 54 had nearly doubled that.

2 Roberto Gonzalez Echeverria, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 158. Promoters from Cuba visited Ruth in August, and in early September signed him to play postseason games on the island. See “Want Ruth in Cuba,” New York Times, August 7, 1920: 6, and “Ruth Signs Contract for Series in Havana,” Chicago Tribune, September 9, 1920: 19.

3 Gonzalez Echeverria, 160. The average net annual income for US citizens filing tax returns in 1920 was $3,269.40. See Treasury Department, United States Internal Revenue, Statistics of Income from Return of Net Income for 1920 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1922), 2. In Cuba, it was less, but perhaps not as much less as some might think. In 1929, it was reported to be 41 percent of the US total (and thus higher than states like Mississippi and South Carolina.) See Marianne Ward (Loyola College) and John Devereux (Queens College CUNY), “The Road Not Taken: Pre-Revolutionary Cuban Living Standards in Comparative Perspective,” 30–31, cited at econweb.umd.edu/~davis/eventpapers/CUBA.pdf.

4 The park was located where Havana’s National Bus Station is in 2019. The first Almendares Park, property of the Zaldo family, was located a few blocks away from the second. There is sometimes confusion over whether Ruth played in the first or the second. The first Almendares Park hosted the Cincinnati Reds, the New York Giants, and the Detroit Tigers. Cooperstown Hall of Famer Jose Mendez Baez cemented his fame in that ballpark. The Almendares Park in question, where Ruth played, has perhaps this visit and Cristobal Torriente’s exploits as the most attractive historical fact.

5 Charles C. Alexander, John McGraw (New York: Penguin Books, 1988), 216.

6 Gonzalez Echeverria, 162.

7 Yuyo Ruiz, “The Bambino Visits Cuba 1920,” undated pamphlet self-published by the author in San Juan, Puerto Rico, 14.

8 Ibid.

9 Figueredo, 134.

10 baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/torriente-cristobal, accessed October 14, 2018.

11 Gonzalez Echeverria, 161. The author notes that most home runs in the ballpark were inside-the-park home runs.

12 Peter Bjarkman, “Cristóbal Torriente,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/1755c43c

13 Alexander, 227. In the aftermath of the 1919 World Series scandal, Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis forced McGraw and Stoneham to divest their interests in the Havana casino, which they did in July 1921. See Alexander, 229.

14 “Ruth Plays Role of Innocent Abroad on His Visit to Cuba,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1921: 6. The story also said Ruth had lost $35,000 in a film venture and was accompanied by a photograph of the Babe under the caption “No Hero of Finance.”

15 “Giants Back from Havana,” The Sporting News, December 2, 1920: 3.

16 Gonzalez Echeverria, 162.

17 Gonzalez Echeverria, 136. The players on the Giants team were Earl Smith (C), Frank Snyder (C/OF), George Kelly (1B/P), Larry Doyle (2B), Frank Frisch (3B), Dave Bancroft (SS), George Burns (OF), Ross Youngs (OF), Babe Ruth (OF/1B/P), Jesse Barnes (OF/P), Pol Perritt (P), and Rosy Ryan (P).

18 Ruiz, 23.

19 Andres Pascual, “Babe Ruth in Santiago de Cuba,” seamheads.com, November 1, 2011. seamheads.com/blog/2011/11/01/ruth-en-santiago-de-cuba-babe-ruth-in-santiago-de-cuba/.

20 Ruiz, 21.

21 “Giants Back Home from Cuban Trip,” New York Times, November 20, 1920: 20.

22 “Giants Back from Havana.”

23 “Ruth Plays Role of Innocent Abroad on His Visit to Cuba.”

24 “Ruth Falls Short on Clouts in Cuba,” Washington Post, November 19, 1920: 12.

25 The box scores do not include bases on balls or runs batted in, so it is impossible to know for sure how many Ruth had of either.

26 “Ruth Writes of His Hopes,” The Sporting News, December 2, 1920: 8.

27 Andres Pascual.