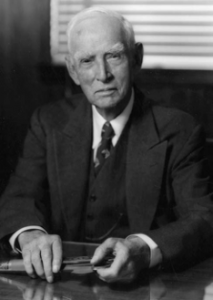

Clark Griffith

This article was written by No items found

This article was published in The National Pastime: Monumental Baseball (Washington, DC, 2009)

As the owner of the Washington Senators, Clark C. Griffith occasionally visited the White House.

As the owner of the Washington Senators, Clark C. Griffith occasionally visited the White House.

Sometimes during the early 1950s, Griffith brought along a guest.

“It was a tradition every spring,” said Clark Griffith, a great-nephew of Clark C. Griffith, “to present the president an annual pass to our grounds [Griffith Stadium]. Several times he took me along. I got to meet Truman and Eisenhower.

“The most memorable time, I was probably around ten years old, we were in the Oval Office, [and] I took a bottle opener off the president’s desk. President Truman saw me take it. He told me that I could keep it.” More than fifty years later, the bottle opener sits on Griffith’s desk in his Minneapolis office. The bottle opener is just one memento for Griffith, who was exposed to the family business of baseball as a teenager in the nation’s capitol.

At an early age Griffith, who was born in 1941, talked baseball with a great-uncle—his namesake, Clark C.—and an uncle, Joe Cronin, who are now in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and two other uncles, Sherry Robertson and Joe Haynes, who also played major-league baseball. Griffith’s father, Calvin, took over running the Senators for Clark C. Griffith.

“The thing is, [you] certainly grew accustomed to talking baseball,” recalled Griffith. “You were expected to have a sufficient knowledge of baseball. The way you watch the game changes. Sitting with Hall of Fame players, you watch the game with a new intensity. You watch every game that way.”

In a family of baseball players, Griffith gives a lot of credit to his mother for his knowledge of the game. “My mother [Natalie] had grown up going to [minor-league] games in Charlotte with her father,” said Griffith. “She had a faultless ability to evaluate players.” Griffith’s mother also made sure that young Clark Griffith got to know his great-uncle, Clark C., before the man died in 1955, less than a month shy of his eighty-sixth birthday.

“I was fourteen, a freshman in high school, when he died,” said Griffith. “My mother, in her infinite wisdom, took me to his house to visit him. I’d sit on a sofa, and he’d sit in his big chair. He told about his life in Missouri and on the frontier in the 1870s [Clark C. Griffith was born in Clear Creek, Missouri, in 1869]. He had met Jesse James as a kid. He took care of Jesse’s horse. Jesse had dinner at his house. Growing up in Missouri, he had to shoot his breakfast a lot.

“He talked about Montana [Clark C. Griffith and his brother owned a ranch there] and riding horses and hunting. I have a rifle—an 1894 Winchester— mounted in my office that was his.”

Clark C. Griffith had been a successful pitcher in the National League in the 1890s and played a big role in the formation of the American League in 1900. In 1912, he became a minority owner of the Senators.

“He once threw 353 innings [for the Chicago Cubs, called the Colts back then, in 1895] and he was a big union guy,” said Griffith. “The Major League Baseball Players Association once told me that they accepted me because I was a descendant of a union organizer.” Griffith’s uncles all shared their baseball knowledge and experiences with him.

“All four knew it [baseball] in subtle ways,” said Griffith. “I used to sit with Clark at games, I was maybe ten years old. He’d have a big stogie in his mouth. He’d say to me, ‘the third baseman just moved, why did he move?’ What I learned was that he moved according to the situation and you have to pay attention to these things. To this day, when I watch a game, I watch several players at a time. That’s what you’re supposed to do.

“Joe Cronin liked to talk strategy of hitting. He had a .301 lifetime batting average [in a major-league career that lasted from 1926 to 1945]. He talked about pitchers tipping off pitches and trying to pick off signs. He’d give you a running commentary about how the situation changed on every pitch.

“Sherry was a good ballplayer. [He spent ten years in the major leagues.] He always liked to tell me the story about the time he almost hit a third home run in a game at Fenway.” On August 18, 1950, Robertson hit two home runs—the only two he hit that year and, as it turned out, the last of his career.

“Joe Haynes liked to talk about pitching,” Griffith continued. Haynes won 76 games in a 14-year majorleague career. “But he’d also want to talk about the time he hit a home run.”

By the time he was fourteen, in 1955, Griffith had started working in concessions at Senators home games. “I loved baseball,” said Griffith. “It was a time in my life where I was focused on school and academics, social life and going to games in the summer.”

Griffith also played baseball. One American Legion game is still memorable for Griffith.

“In the late ’50s, 1958 or 1959, we played an American Legion game on a field on the Ellipse. There were four baseball fields on the Ellipse. There were probably 5,000 people watching our game. They were lined sixdeep all around the field. The game ended at dusk. After the game ended we went to the Senators game and there was nobody there. One guy, who had been at both games, told me there were people at the legion game,” said Griffith.

Griffith fondly remembers being around Griffith Stadium and the team in the late 1950s.

“Sherry ran the minor leagues,” said Griffith. “He took over for Ossie Bluege [who had spent 18 years in the major leagues, exclusively with Washington], who was better as an accountant. The team always had great relationships with its scouts. We developed players like Harmon Killebrew, Jim Kaat, Zoilo Versalles, and had pretty good teams by the late 1950s.”

The Senators’ final season in Washington was in 1960. In October of 1960, Calvin Griffith announced he was moving the franchise to Minnesota. Washington was quickly given an expansion team, which began play in 1961.

“When old Clark was in charge,” said Griffith, “baseball was a small business. The stadium that changed everything was County Stadium in Milwaukee. It changed everything [when it opened in 1953]. It was a big place. It was like the HMS Dreadnought, the first real battleship. Everything changed after that.”

As the Senators were leaving Washington for Minnesota, Griffith went off to college at Dartmouth. After college, Griffith worked for his father and the Minnesota Twins. Today, Griffith, a lawyer who works in business law, is still connected to baseball as the commissioner of the independent Northern League.

Sources

Interview with Clark Griffith, September 2008.

National Baseball Hall of Fame, www.baseballhalloffame.org/.

The Baseball Biography Project, SABR.

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella, The Ball Clubs. New York: HarperPerennial, 1996.

The Baseball Encyclopedia. 10th edition. New York: Macmillan, 1996.