Comprehending Koufax: Biographical Interpretations of an Intensely Private Man

This article was written by Charlie Bevis

This article was published in Sandy Koufax book essays (2024)

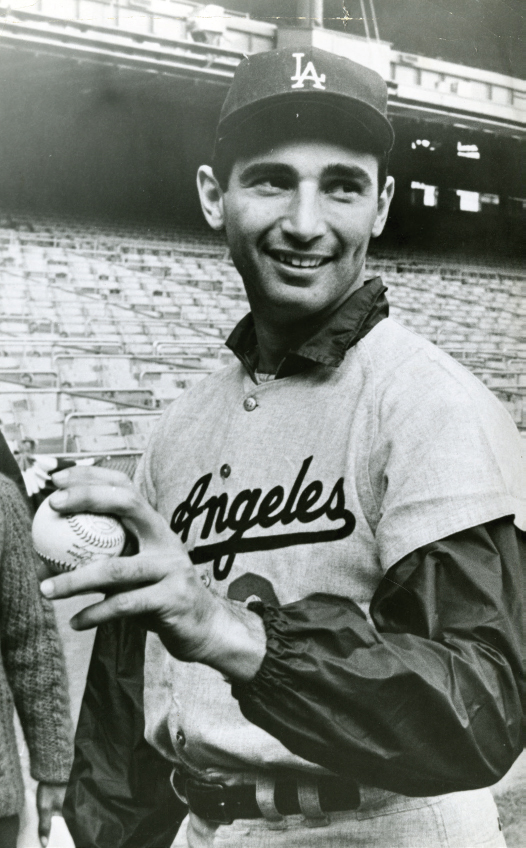

Several authors have given readers a glimpse of Sandy Koufax’s life and career. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Beneath the orderly reporting of baseball accomplishments that Sandy Koufax compiled in nine-inning ballgames over 162-game seasons and several World Series is a much less well-structured human narrative about the man.

Terms such as “the J.D. Salinger of baseball,” “a Greta Garbo-like isolation,” and more simply “reclusive” have all too often been deployed to one-dimensionally characterize Koufax, the result of his infrequent interactions with the media after his Hall of Fame enshrinement in Cooperstown in 1972. The nature of the introverted, unassuming Dodgers left-handed pitcher is much more nuanced.1

It is relatively easy to refute the “reclusive” label tagged on Koufax from an empirical perspective, since he was not bashful about participating in occasional public events. For instance, Koufax appeared at a White House ceremony in 2010 at which President Obama quipped, “Sandy and I actually have something in common–we are both lefties. He can’t pitch on Yom Kippur; I can’t pitch.” It is the intellectual aspect of reclusive as a Koufax character trait that has had long-lasting impact, due to the lack of suitable substitute descriptors. This is largely because only a few biographies have examined Koufax.2

This article probes four aspects of the biography production relating to Koufax: (1) the 1966 autobiography ghostwritten by Ed Linn and its implicit character revelations, (2) the dearth of biography published about Koufax during the next three decades, (3) the books by Ed Gruver and Jane Leavy published at the turn of the twenty-first century that provide some understanding of the existential Koufax, and (4) the possibility of future biographies of Koufax.

Biography is the window into the character of a public figure, far more than a simple recounting of the facts of a person’s life. In his seminal history of biography, Nigel Hamilton succinctly defines the essence of this literary genre as “the life and character of a distinctive human being.” Another literary historian describes the biographer’s most vital task as “the explanation which lies behind the facts, the interpretation which will explain the progress and decline” of the subject’s life.3

Character assessment is the most difficult aspect of the subgenre of baseball biography, compared with its other components of life’s work in the baseball industry, the person’s cultural/societal impact, and the writer’s quality of research evidence. Developing a subject’s character is no easy task. Most biographers don’t discover their subject’s character as a distinct piece of the research evidence, as if the quest were a complex scavenger hunt. Biographers almost always form character traits out of tidbits of the research examined, which is more like putting together a jigsaw puzzle without all the pieces being readily available. Inevitably, character assessment is informed inference, not a definitive conclusion, and thus subject to continual debate. This is especially the case with the very private Koufax.4

Several of Koufax’s inherent character traits, though, have been hiding in plain sight for nearly 60 years–in his 1966 autobiography that still sits on library shelves across America. Ed Linn, the ghostwriter of that book, essentially functioned as a biographer who wrote in the first-person point of view. Through his structure of the book and the depth of the particular topics covered in it, Linn reveals much about the underlying nature of Koufax.

Autobiography of Koufax

When this book was published in 1966, Koufax was not yet labeled a recluse, as he tried to navigate the brave new world of the 1960s regarding sports celebrity status. The book was published in the fall of 1966, before Koufax shocked the sports world by announcing his retirement from baseball at age 30. The one-word title Koufax, with no modifiers or subtitles, provides a distinct peek into the inner Koufax.

By revisiting this autobiography, four value-driven tenants of Koufax’s character can be gleaned from Linn’s text: (1) integrity, (2) humility, (3) craftsmanship, and (4) trusting nature. The first three characteristics are fairly straightforward interpretations. The fourth one is less obvious but is supported by recent academic research and importantly helps to explain Koufax’s intense desire for privacy that has provoked so many writers to evoke the Salinger and Garbo analogies.

Linn demonstrates integrity through the handshake arrangement prior to Koufax’s actual initial contract with the then Brooklyn Dodgers, a $20,000 deal consisting of a $6,000 salary and a $14,000 bonus that roughly equaled the cost of a college education. Irving Koufax, the pitcher’s father and an attorney, shook hands with Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley in the interim period before a roster spot was available. Koufax could welsh on the deal and besmirch his father’s reputation (his word was his bond) by taking a better offer from another team. “But any deal that you make for me, even if I never pitch another game in my life, I will stick by,” Linn wrote about Koufax’s stance. He actually turned down more money from the Pittsburgh Pirates, with whom he would have had a more immediate chance to actually pitch rather than sit on the bench.5

Humility is readily apparent through Linn’s penning of the Koufax remarks that “I don’t think ballplayers are really entertainers” or even “of any extraordinary importance in our natural life” as they “do not heal the sick or bring peace and comfort to a troubled world.” Later in the book, Linn gives ample credit to several people for making Koufax a baseball success, notably statistician Alan Roth in an era well before sabermetrics. “I made the transition from thrower to pitcher and had not understood that in making the transition I had made a beginning, not an end,” Linn wrote on behalf of Koufax. “You become a pitcher before you become a good pitcher.” As a paean to Roth, Linn includes 18 pages of Roth’s statistics in an appendix.6

Roth enabled Koufax to become a craftsman at his profession, a seeker of intimate knowledge about his craft, not just to excel at the strategy of the ballgame. Koufax sought also to improve his baseball output by understanding the medical aspects of his left arm. Here, he was tutored by Dr. Robert Kerlan. Linn details a number of arm injuries and recoveries plotted by Kerlan, as Koufax understood that his arm “had passed over the line between temporary change and permanent trouble,” after “an arthritic change had taken place.”7

Linn illustrates Koufax’s trusting nature as the foundation of the opening chapter, where Koufax is infuriated by a Time magazine story published after the 1965 World Series in which the magazine “managed to gather together all the myths into one great orgy of myth-making.” In the book’s opening paragraph, Linn writes that Koufax wants to bury “the myth of Sandy Koufax the anti-athlete” who supposedly has “regretted–and even resented–the life of fame and fortune that has been forced upon me.”8

Later in the book, Linn details another example of Koufax’s trusting nature with his extreme dismay at the gamesmanship and deception employed by Dodgers management in his 1964 salary negotiation, a process that he terms “negotiation by ultimatum.” What particularly rattled Koufax was the demand that he refrain from negotiating his salary through the newspapers, but then management did just that to push its position. Koufax was cornered into agreeing to a $70,000 salary after the Dodgers had inaccurately told the newspapers that he wanted $90,000. After the conclusion of the negotiation, Koufax (through Linn) says, “All right, I’m signing this as we agreed. But I want you to know that I’m not happy about it. It’s not that I’m not happy with the money. I’m just not happy about the way it was done.”9

The veracity of revelations in any autobiography is, of course, subject to the author being a reliable narrator. Gruver’s 2000 biography provides reliability by articulating Linn’s take on Koufax’s motive for writing the book: “One of the reasons Koufax agreed to do his autobiography before the ’66 season was because he knew he was going to hold out and didn’t want to feel pressure for money.” As Gruver writes about the famous Koufax/Drysdale joint holdout in the spring of 1966, “Koufax strengthened his position by accepting $100,000 to do his autobiography with Ed Linn.”10

Additional reliability, and support for the view of his trusting nature, comes from current-day experts who study generations. Koufax was a member of the Silent Generation, those Americans born between 1925 and 1945, which influenced the shaping of his values and motivations, i.e., his inner character traits. According to psychology professor Jean Twenge in her analysis of generational differences, Silents are “more likely to trust others, and more likely to see the good in people,” in line with the those in the preceding Greatest Generation, more than the following Boomer Generation, and much more than the next subsequent Generation X grouping.11

Besides this higher level of trust in others, Silents also “lived their young adulthood in a more collectivistic, family-oriented time in American history.” However, Silents were snagged in a societal transition when “American culture began the 1960s as a collectivistic culture (focused on social rules and group harmony) and ended it as an individualistic one (focused on the needs of the self and thus often rejecting traditional rules).” From the 1970s forward, individualism trended higher with each subsequent decade.12

Some Silents adapted to the new individualism and the emerging celebrity culture; others like Koufax held steadfast. The celebrity life was not something Koufax inherently wanted, nor as a Silent was it something he could philosophically handle. Koufax was a man seemingly locked into the mentality of the 1940s. He was highly resistant to the societal changes of the 1960s, which were just unfolding when the Koufax autobiography was published in the fall of 1966.

The value system of many Silents was largely binary in nature, i.e., right/wrong, true/false, black/white with no gray area. Koufax, like many members of the Silent Generation, seemed to possess this mindset. Certainly, Koufax’s own chosen profession reinforced this absolutist nature, with its dichotomous orientation of ball/strike, safe/out, and fair/foul. It’s also reasonable to assert as an extension that Koufax would also strictly demarcate work life from nonwork life.

While Koufax’s autobiography reportedly sold 32,000 copies by the end of the 1966 World Series, subsequent sales were lackluster. Three years later, only 40,000 copies had been sold, “well short of the 100,000 breakeven point” for the publisher to turn a profit. The great Dodgers pitcher, true to the underlying character traits exposed in the book, was not congenitally a star pitchman for his own book.13

Given the book’s concealed insights into the mindset of Koufax, it’s a shame that Linn’s work isn’t more widely available today or at least digitally accessible through Google Books. Several hundred copies of the book are maintained in US libraries (according to records at the World Cat website), but the majority are housed in academic libraries generally inaccessible to the public. Public libraries have some copies, but those that have survived culling from the collection due to age or diminished borrower demand are too often in rough physical shape after six decades on the bookshelf.14

Dearth of Koufax Biographies

When Linn wrote the Koufax autobiography, the subgenre of baseball biography was in its infancy. Baseball biography during Koufax’s 12-year major-league career was almost exclusively published as hero-worshipping books for the juvenile audience, youngsters under age 14. Koufax’s ghostwritten autobiography was then state-of-the-art in life writing about baseball players.15

During the early 1960s, there was almost no market for baseball biography as we know it today, i.e. for adult consumption, particularly regarding living ballplayers like Koufax. Publishers were leery of potential litigation for libel since truth was then not necessarily a viable defense to many assertions of libel. The landmark 1964 US Supreme Court decision in New York Times v. Sullivan changed this publishing perspective, when the justices ruled that public figures must demonstrate that publishers acted in “reckless disregard” of a statement’s truth or falsity. The standard of “actual malice” limited the libel risk for publishers and opened a nascent market for objective, third-party baseball biography.16

After Robert Creamer initiated modern baseball biography with his insightful 1974 book Babe: The Legend Comes to Life, sportswriter Maury Allen wrote numerous books about ballplayers and became a prolific author in the evolving craft of baseball biography. Allen, though, did not include Koufax among his multiple ballplayer subjects. Had there been an Allen-crafted biography of Koufax, readers probably wouldn’t have learned much more about him, since Allen was notorious for concentrating on the baseball activities of his subjects and never delving too deeply, if at all, into character assessment.17

Allen likely avoided Koufax as a biographical subject due to his run-in with the pitcher back in 1963 when Allen revealed that Koufax was adopted and interviewed his biological father for an article in the New York Post. Demonstrating his trusting nature, Koufax believed this was not just a breach of old-school ballplayer-sportswriter journalistic etiquette, but also a violation of the work/nonwork bifurcation of his life. Although what Allen wrote was the truth, Koufax surely considered that Allen lacked integrity by divulging this fact.18

In part because Allen did not write a basic, baseball-oriented biography of Koufax, there was a three-decade dearth of Koufax biographies.

During the 1980s, while Allen pursued the popular approach to baseball biography, history professor Charles Alexander produced several scholarly biographies of deceased ballplayers. The efforts of Alexander and other professional historians moved the baseball biography subgenre into examining the cultural and societal impacts of ballplayers during the 1990s, as notably exhibited by the Nicholas Dawidoff biography of Moe Berg–a work that also raised the standard for character assessment–and the Arnold Rampersad biography of Jackie Robinson to mark the 50th anniversary of racial integration in professional baseball.19

A general market also developed in the 1990s for straightforward biographies of Hall of Fame ballplayers, which led Ed Gruver to fill the void left by Maury Allen to research the first book-length biography of Koufax.

First Koufax Biography

The Gruver biography of Koufax published in 2000, succinctly titled Koufax like the Linn-ghostwritten book, is a classically written baseball biography, focused on the arc of his baseball career, in particular an in-depth look at Game Seven of the 1965 World Series. “I wanted to illuminate what I feel is Sandy’s greatest game and one of the best pitched games in World Series history,” Gruver recalled in 2023. “I believe I did that with the aid of recollections from his Game 7 opponents–Harmon Killebrew, Tony Oliva, Jim Kaat, et al.”20

Gruver also contributes some insights into Koufax’s character. “Gruver interviewed many of Koufax’s teammates and opponents, but even as they sing the tributes in personality and achievement of the reclusive Koufax, he remains an enigma,” the New York Times noted in its review of the book. “Although Koufax appeared to the public as reclusive and guarded, he was actually a shy, self-effacing, and private person who really didn’t want the spotlight,” another book reviewer described Gruver’s characterization of Koufax.21

The book’s most valuable contribution to understanding Koufax is Gruver’s peek inside the mind of ghostwriter Linn, which he obtained from interviews with him before his death in 2000. “He is reclusive,” Linn told Gruver. “He has tremendous integrity. He could have been the first merchant prince of baseball, but he decided he wasn’t going to sell his name. He turned down massive amounts of money.” Even though Koufax was forthcoming in his conversations with Linn for the book, Linn “had the feeling that Koufax was forever holding something back”; he referred to it as “a wall of amiability.”22

Gruver also adds color to the character traits that anchored Linn’s book about Koufax. In craftsmanship, Gruver delves into the role of catcher Norm Sherry in 1961 to inspire Koufax’s pitching evolution. Gruver also demonstrates the trusting nature of Koufax, through his complicated relationship with the sports media from 1963 to 1966 and its sometimes casualness with the truth. Gruver shows Koufax’s integrity, writing that “while patient and polite,” he was “clearly uneasy” talking to the media, finding it “embarrassing” to be a craftsman thrust into the role of celebrity.23

Koufax’s post-1966 life is covered in the Gruver biography, which obviously was not explored in Linn’s book, including his retirement as a player and his stint as an NBC television broadcaster. Gruver corroborates the Linn-inspired character traits in these sections, writing about the integrity of Koufax in wanting the ability to use his left arm for the rest of his life, not more money to keep pitching, and the extent of his baseball craftsmanship as Koufax had difficulty coping with the entertainment nature of television.24

Second Koufax Biography

Jane Leavy’s book Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy captures the broad essence of Koufax’s character, based on her 469 interviews, which she largely confines to the book’s preface rather than rigorously develop within the main text.

“Koufax spans two distinct eras in baseball and America,” she presciently observes. “Koufax is the sixties before the sixties became the sixties,” adding that “he is hound’s-tooth, a crisp white shirt and a skinny black tie held in place by a discreet gold tie tack.” Left unsaid is that his values are of another era than the 1960s we know today (or as Leavy knew in 2002); Koufax’s values are from the Silent Generation that grew up in the 1940s. She also refutes the ever-present “recluse” branding of the man: “Koufax cherishes his privacy. Yet an individual who chooses to do so, to keep an inner life inner, is deemed reclusive, enigmatic, aloof … [and] is thought odd.”25

In post-publication interviews and articles, Leavy articulates more about her perspective on Koufax’s character beyond the material included in her book.

“The myth I was deconstructing was not the usual one of hubris brought low. The revelation here was character,” Leavy wrote in a New York Times article about her book. “We live in a culture where it is considered daring to be kind. Skepticism has purchase on our souls. What if the inside story is too good to be true? What if the lefty’s legacy is one of uncommon grace and decency?” Leavy added, “The word used most often to describe him was ‘gentle.’ The nicer he appeared, the more miserable I got. When people asked what kind of guy he was, I was embarrassed to tell the truth. It felt almost unprofessional.” She concluded: “The man is not without flaw or complication or idiosyncrasy. He can be testy, especially with fund-raisers looking to exploit his name for their own purposes. He is capable of not telling the truth, the whole truth, but is incapable of lying.”26

“Koufax gave the impression by the way he left the game that he didn’t need baseball to know who he was,” Leavy told a book reviewer for the Los Angeles Times. “I don’t think Koufax wanted to spend his life being Sandy Koufax, the public persona. I think he wanted to be himself. It was a radical thing to do. The Koufax persona seems part of a world apart from today’s baseball industry.” She then observed, “He was bigger than winning. He’s an American icon as much for what he refused to do as what he did on the field. The defining differences of Koufax’s career weren’t economic. They were moral, and bound up with a sense of responsibility to his teammates and the game. In every way that matters, he offers a barometer—a way of measuring where we were and where we’ve come to.”27

One interview with Leavy resulted in an article title that seemingly captures the essence of the man’s character: “Koufax: The Pitcher as a Mensch.” “Mensch” is the Yiddish word for “someone of consequence, someone to admire and emulate, someone of noble character” who exudes “rectitude, dignity, a sense of what is right, responsible, decorous.” There is no comparable word in the English language that equates to the solemn overtones of the Yiddish term.28

Leavy did not pursue a more extensive character assessment in her book because she was stymied by the always contentious quandary for a biographer—the conflict between commercial element (book sales) and intellectual inquiry (exposing the soul of the subject). The thesis of Koufax as a “nice guy” wouldn’t sell many books. Lacking a saleable character theme, Leavy adopted an unusual structure for her book. “This won’t be so much a biography, I told Koufax, as a social history of baseball, using his career as a way to measure how much has changed. My aim, I said, is to limn the trajectory of his career and in so doing recreate that time in baseball and America when change was imminent, when a well-placed tie tack held it all at bay.”29

She focuses on Koufax’s contribution to cultural impact, an important element of baseball biography that was just emerging in the 1990s. Leavy’s not-a-biography book is organized into 22 chapters. There are 12 odd-numbered chapters that are slices of Koufax’s career, ostensibly cut by time periods but that also align with a variety of cultural impacts, and 10 even-numbered chapters that are slices of Koufax’s perfect game pitched in September 1965, cut by pregame and the nine innings.

While Leavy didn’t set out to expand upon the implicit character traits embedded within Linn’s ghostwritten autobiography of Koufax, most of the dozen career-related chapters do advance beyond cultural impact to map to one of the four Linn-inspired character traits. For example, Chapter 13 focuses on the new chipmunk-style of sportswriting, but delves into his trusting nature, while Chapter 17, which focuses on Yom Kippur, also discusses integrity.

Given the challenge to adequately portray the character of Koufax, the book reviews were a mixed bag. The New York Times sniffed, “We scarcely know Koufax at all, but after Jane Leavy’s delightful ‘Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy,’ we probably know him as well as anyone needs to.” The academic journal Aethlon was more charitable: “Her book is as much a cultural commentary and a eulogy for a lost Golden Age as it is biography. If Koufax’s public deeds are heroic (by our debased standards, of course, ‘super’ heroic), then his silence, both about those deeds and about the private man who performed them, becomes, in an Age of Blab, nothing short of Olympian.”30

Although not the plan, Leavy did advance the world’s knowledge of Koufax’s character. Leavy’s observations don’t jump off the page at the reader, though, as the reader must think into her subtle references to paint the inner mindset of Koufax. He is a private man in a celebrity-crazed culture who never tried to capitalize on his baseball fame and wants to be just an ordinary, modest, decent person far removed from the sports spotlight.

Leavy in 2002 had the last word on Koufax. No writer in the next 20 years attempted to write another book-length biography of Koufax.

Future Koufax Biographies

There likely will never be another Koufax biography to top Leavy’s work. As Mark Armour writes in his tribute to Leavy as a Chadwick Award winner in 2022, she “got as close to Koufax as we likely ever will, or will ever need to.”31

To make a new biography viable, there would need to be the discovery of a new research source that disclosed some revelatory thoughts from Koufax (such as a diary or archive of papers) or about him (such as court records) or notes from Linn’s ghostwriting conversations with Koufax. The latter approach enabled Jeff Pearlman to write his 2022 biography of Bo Jackson (another legendary athlete who avoided a public life after his baseball days) when he discovered at an Auburn University library the interview tapes used by a ghostwriter to pen Jackson’s autobiography decades earlier.32

Barring the discovery of new research evidence, any new Koufax biography that simply focuses on his post-1966 life and activities—little remarkable there—or a deep dive into his personality or character—of marginal interest to modern-day sports fans—would probably be a poor business proposition, with not enough projected sales volume to justify the expense of such a project.

The sports world likely needs to be satisfied with the existing interpretations in the books written by Linn, Gruver, and Leavy (and thoughts in this essay) to convey a comprehension of the inner Koufax, a quintessential representative of the Silent Generation.

is the author of Baseball Biography: A Comprehensive History, a web-book freely accessible on his website, Bevis Baseball Research. During his 40 years as a researcher and writer of baseball history, he has written eight hard-copy books, two dozen journal articles, and more than 65 biographical profiles for the SABR BioProject. He writes baseball from his home in Chelmsford, Massachusetts.

Notes

1 “SI 60 Q&A: Tom Verducci on Sandy Koufax and ‘The Left Arm of God’,” Sports Illustrated website, August 25, 2014, https://www.si.com/mlb/2014/08/26/si-60-qa-tom-verducci-sandy-koufax-left-arm-god; David Kaufman, Jewhooing the Sixties: American Celebrity & Jewish Identity (Waltham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2012), 46.

2 “Remarks by the President at Reception in Honor of Jewish American Heritage Month,” Obama White House press release, National Archives website, May 27, 2010, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/realitycheck/the-press-office/remarks-president-reception-honor-jewish-american-heritage-month.

3 Nigel Hamilton, Biography: A Brief History (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007), 26; Edward O’Neill, A History of American Biography 1800-1935 (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1935), 8.

4 Charlie Bevis, Baseball Biography: A Comprehensive History (self-published web-book, 2021), chapter 7, paragraph 2. This web-book can be accessed at https://bevisbaseballresearch.wordpress.com/research-archive/baseball-biography-a-comprehensive-history/.

5 Sandy Koufax with Ed Linn, Koufax (New York: Viking Press, 1966), 66-67.

6 Linn, Koufax, 157.

7 Linn, Koufax, 225.

8 Linn, Koufax, 1, 4.

9 Linn, Koufax, 269, 283.

10 Edward Gruver, Koufax (Dallas: Taylor Publishing, 2000), 197-198, 200.

11 Jean Twenge, Generations: The Real Difference Between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents–And What They Mean for America’s Future (New York: Atria Books, 2023), 196-197.

12 Twenge, Generations, 56, 84.

13 Jerome Holtzman, “Supreme Test for Sandy’s Arm: Inking Copies of His New Book,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1966: 27; Marvin Kitman, “Some Serious Writers Are Ballplayers,” New York Times, November 23, 1969: book section, 72.

14 The author thanks the Winthrop (Massachusetts) Public Library for having retained a copy of the Koufax autobiography and making it available to borrowers in other Massachusetts library systems. The book in Winthrop is a sad testament to the ravages of time. The dust jacket is long gone; the title on the spine is barely legible; the back cover hangs on literally by a few threads to the spine; the pages are stained, dog-eared, and brown from acid deterioration; and the book tilts at a 60-degree angle. Inside the back cover, there is a flap holding an antiquated check-out card with stamped entries (last due date: August 15, 1977), with a modern bar-code label affixed above it.

15 Bevis, Baseball Biography, chapter 5, paragraphs 1-4. There were a few youth-oriented Koufax biographies published, which focused solely on his baseball achievements.

16 Anthony Lewis, Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment (New York: Basic Books, 2007), 54-57; Bevis, Baseball Biography, chapter 5, paragraphs 17-18.

17 Bevis, Baseball Biography, chapter 6, paragraphs 16-17, 35-36.

18 Jane Leavy, Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy (New York: HarperCollins, 2002), 129-130.

19 Bevis, Baseball Biography, chapter 6, paragraphs 29-34, and chapter 8, paragraphs 8-12, 25-28, 35.

20 Gruver, email to author, February 27, 2023.

21 Michael Lichtenstein, “Baseball Books in Brief,” New York Times, July 2, 2000: section 7, 15; Jim LaFollette, Koufax book review, NINE: A Journal of Baseball History & Culture, Fall 2001, 177-180.

22 Gruver, Koufax, 4-5.

23 Gruver, Koufax, 126, 172-174.

24 Gruver, Koufax, 212, 217.

25 Leavy, Sandy Koufax, xvi, xix.

26 Jane Leavy, “Tape From 1965 Easier to Find Than Ill Will Toward Koufax,” New York Times, September 1, 2002: section 8, 6.

27 Josh Karp, “Searching for Sandy Koufax,” Los Angeles Times website, October 20, 2002, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-oct-20-tm-crkoufax42-story.html.

28 Todd Leopold, “Koufax: The Pitcher as a Mensch,” CNN website, October 18, 2002, http://www.cnn.com/2002/SHOWBIZ/books/10/18/koufax.leavy/; Leo Rosten, The New Joys of Yiddish (New York: Crown, 2001), 232-233.

29 Leavy, Sandy Koufax, xvii.

30 Allen Barra, “Artful Dodger, Damn Yankee,” New York Times, October 13, 2002: section 7, 18; Robert Lee Mahon, Sandy Koufax book review, Aethlon, Spring 2004, 110.

31 Mark Armour, “2022 Chadwick Awards: Jane Leavy,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2022, 118.

32 Jeff Pearlman, The Last Folk Hero: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson (New York: Mariner Books, 2022), 435.