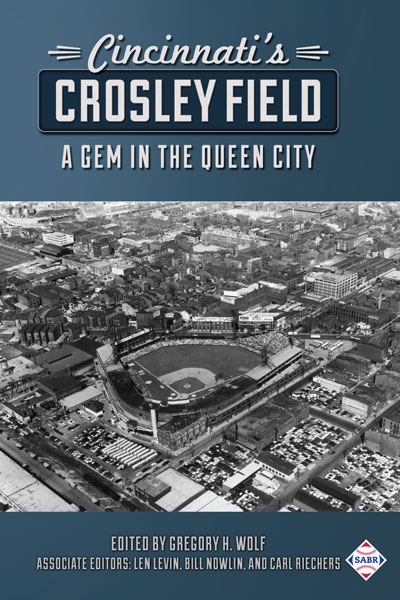

Crosley Field: Goat Run

This article was written by Greg Rhodes

This article was published in Crosley Field essays

In 1946, Warren Giles, then the president of the Reds, added a section of temporary seats in front of the right-field bleachers. This section must have suggested an animal pen to the writers and other ballpark denizens, for it soon became known as “Giles’s Chicken Run” and later the “Goat Run.”1 The result was twofold: It increased seating capacity in the smallest ballpark in the majors, and shortened the longest right field in the majors.

In 1946, Warren Giles, then the president of the Reds, added a section of temporary seats in front of the right-field bleachers. This section must have suggested an animal pen to the writers and other ballpark denizens, for it soon became known as “Giles’s Chicken Run” and later the “Goat Run.”1 The result was twofold: It increased seating capacity in the smallest ballpark in the majors, and shortened the longest right field in the majors.

The trapezoidal shape of the street grid bordering Crosley Field yielded a right-field line that was always longer than left field. Since 1938 (when the Reds moved home plate out some 20 feet), the right-field distance stood at 366 feet, the longest in the major leagues (while left field was 328 feet). As the 1946 season approached, Giles decided to give a boost to his offense and brought in the right-field fence some 24 feet, reducing the line distance to 342 feet. The new fence angled in from the line, narrowing in deep right-center where it met up with the old fence in front of the grandstand. At its widest near the foul line, the Goat Run could hold eight additional rows of seats, and altogether provided additional seating for several hundred fans.2

The decision was a little puzzling. The Reds of the late 1940s were not much of an offensive team, and despite the presence of Ewell Blackwell, not much of a pitching threat either. Giles did have a new left-handed bat in the lineup in Grady Hatton and a left-handed slugging prospect in the minors named Ted Kluszewski, but the Reds lacked a powerful lineup that could take much advantage of the shorter fence. But neither could the opposition. In 1949 opposing teams hit only one more home run into the Goat Run than did Cincinnati.3 Hatton failed to benefit, averaging just over eight home runs a year at Crosley Field from 1946 to 1949.

In June of 1950, with the Reds deep in last place, Giles announced that he was removing the Goat Run while the club was on a 16-game road trip. “It’s about time that the baseball people begin to think of the pitchers,” he explained.4 At that point in the season, the Reds were dead last in runs scored and next-to-last in runs allowed. Whatever impact the Goat Run was having on his team was hard to discern, but Giles must have known something. His Reds did play significantly better after the Goat Run was demolished; they were nine games over .500 at home the rest of the season. Perhaps the pitchers were appreciative.

Warren Giles became the president of the National League in September 1951, and owner Powel Crosley Jr. promoted Gabe Paul to the general manager’s job. Paul admittedly loved power, and he resurrected the Goat Run in 1952. Although as Paul admitted, the Goat Run hadn’t seemed to make much difference to the fortunes of the Reds in the 4½ seasons it was in place, and he didn’t think that the Reds’ record in the future would be “materially affected by the new fence.” So why do it? It would give his players more “confidence,” said Paul. The shorter fence would bring Crosley’s dimensions more in line with those of other ballparks. “I think our club, as a whole, will be more confident with a shorter right-field fence to shoot at,” Paul predicted.5

Confidence and talent proved Paul right. The Goat Run remained in place through the 1957 season, and during that six-year stretch Kluszewski blossomed as one of the league’s leading home-run hitters. He was joined by Frank Robinson, Gus Bell, Wally Post, and Ed Bailey to create one of the great power-hitting clubs of the 1950s. The Reds walloped 221 home runs in 1956 to tie the then major-league record. It is not known how many of those home runs landed in the Goat Run, but without it there would have been no record-tying performance.

But the Goat Run began to be viewed as a double-edged sword. Reds pitchers complained about “cheap” home runs. A poll showed most fans wanted to remove the Goat Run, thinking it was hurting the Reds more than helping. With the Reds struggling to develop pitching, Paul agreed. A week before the 1958 season, the Goat Run was dismantled, with Gabe explaining that it was a mental hazard for his pitchers.6 Paul toyed with the idea of bringing the Goat Run back in 1959, but decided against it. “That goat run gives our pitchers claustrophobia,” Gabe concluded, ending a 15-year experiment with Crosley’s dimensions.7

GREG RHODES, a former chair of the Hoyt-Allen SABR Chapter of Cincinnati, is currently the Cincinnati Reds team historian. He was the founding director of the Reds Hall of Fame and Museum and served as director from 2003-2007. Two of his eight baseball books received The Sporting News-SABR Research Award (Reds in Black and White, with co-author Mark Stang, in 1999 and Redleg Journal, with co-author John Snyder, in 2001), and his book Big Red Dynasty, with co-author John Erardi, was a finalist for the 1998 Seymour Medal.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

(Thanks to Mike Weaver, Crosley Field model builder and historian, and Chris Eckes of the Reds Hall of Fame for their contributions.)

Notes

1 Lou Smith, “Giles Kills Homer Fence, Citing Aid to Hurlers,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 10, 1950: 13.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Lou Smith, “Right-Field Wall at Crosley Field to Be Cut Down Again,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 22, 1952: 32.

6 Earl Lawson, “Tebbetts Has Secret – It is ‘Pinson, R.F.,’” The Sporting News, April 16, 1958: 18.

7 Earl Lawson, “New Boxes at Cincy,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1959: 14.