Crosley Field: The Laundry

This article was written by Greg Rhodes

This article was published in Crosley Field essays

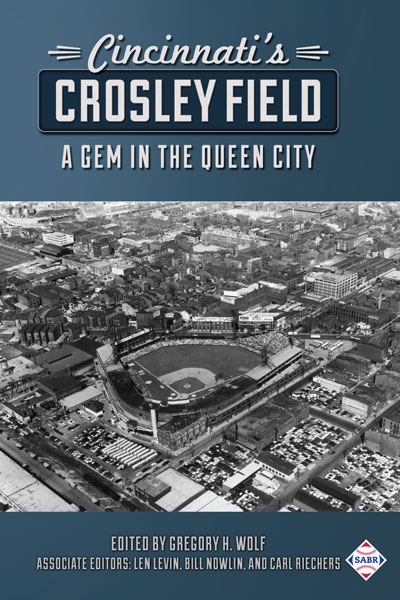

Beyond the outfield walls at Crosley Field, across Western Avenue in center field, and across York Street in left field, were brick industrial buildings, a part of the fabric of the neighborhood that enveloped the ballpark. Spectators sometimes grabbed glimpses of games from the windows of these buildings, and advertisers placed large signs on the rooftops, easily visible to the Crosley patrons. Restaurant, beer, soft drink, and car ads loomed over the walls. It was hard to distinguish between the boundary of the park and the edge of the neighborhood, a seamless transition that was typical of many of the ballparks built in the early 1900s, and mimicked by some of the modern parks. (Petco Park in San Diego is probably the best current example.)

Beyond the outfield walls at Crosley Field, across Western Avenue in center field, and across York Street in left field, were brick industrial buildings, a part of the fabric of the neighborhood that enveloped the ballpark. Spectators sometimes grabbed glimpses of games from the windows of these buildings, and advertisers placed large signs on the rooftops, easily visible to the Crosley patrons. Restaurant, beer, soft drink, and car ads loomed over the walls. It was hard to distinguish between the boundary of the park and the edge of the neighborhood, a seamless transition that was typical of many of the ballparks built in the early 1900s, and mimicked by some of the modern parks. (Petco Park in San Diego is probably the best current example.)

The best known of these Crosley neighbors was the low two-story industrial building just beyond the left-field wall. Beginning in the early 1920s and through the 1960 season, the building housed the Superior Towel and Linen Service, and it was always referred to as “The Laundry,” as though one might drop their cleaning off on the way to the ballpark. But it was a commercial laundry, whose clients included hotels, restaurants, and other large enterprises that dealt in laundry by the truckload.

The laundry was so close to the ballpark that home runs regularly ricocheted off the front of the building, and sometimes landed on the roof. The left-field fence was on the edge of York Street, which was more the size of an alley, about 15 feet wide. The laundry was directly on the other side of the street, some 25 feet from the outfield wall. A drive of 350 feet to straightaway left field could reach the laundry. Fans could easily see the laundry from their seats, and used it as a gauge of a home run’s distance. Longtime Reds announcer Waite Hoyt regularly used the laundry as a reference point: a home run hit the front of the laundry, the ball landed on the roof. Fans listening at home could immediately grasp the trajectory of the blast.

For one brief moment, the laundry was hidden from view from the Crosley fans. For the 1919 World Series, the Reds built temporary bleachers atop the left-field wall. The wooden stands were buttressed by posts anchored against the front of the laundry. The addition added about 4,000 seats, and this was the only time the Reds erected these temporary stands.1

In Brooklyn in the Ebbets Field era, players could win a free suit by hitting Abe Stark’s famous sign on the scoreboard in right-center field. In Cincinnati, the suits were delivered by Siebler tailors, who placed their sign atop the laundry. The billboard on top of the laundry was enormous, about 10 feet high and stretching 131 feet from the foul line into left-center. Siebler’s suit sign was on the left-center-field edge of the billboard, but the offer of the free suit pertained to the entire billboard, not just the Siebler portion.2 The prominent ad on the billboard over the years featured beers (Heidelberg Beer, Bavarian Old Style Beer, Student Prince), but it is the Siebler sign that lives in the memories of Crosley fans.

“Hit This Sign and Get a Siebler Suit Free” was the offer, and over the 20 years Siebler gave away 176 suits, about eight winners a year. And they weren’t off the rack. Jack Siebler recalled that Willie Mays was “surprised to find our line was all custom-tailored. He said he thought it was a ready-made.”3

Siebler had an arrangement with the Cincinnati beat writers to tell the store when a player hit the sign. “We’d send the guy a letter,” Siebler said. “‘Congratulations, slugger. You did it. Come in and pick out any suit in our line.’” Del Ennis, an outfielder with the Phillies and Cardinals in the 1940s and 1950s, once hit the sign twice in one homestand. He came in after the first home run and couldn’t decide on a pattern. Siebler recalled, “He told me, ‘I’ll take this one, but save the other one. I might hit your sign again tonight.’ And he did!” The champion suit winner was Wally Post, who played for the Reds for 12 seasons. The slugger won 11 suits, and admitted he was so appreciative of the Sieblers’ generosity that he bought three more on his own.4

The laundry played a bit role in the 1956 season when the Reds, Braves, and Dodgers careened through the final weeks of the season chasing the National League pennant. The Reds printed World Series tickets, but wound up third, two games behind the Dodgers. A few days after the season ended, a group of Reds employees loaded a million dollars worth of unusable World Series tickets onto a couple of hand carts and pushed them across York Street to the laundry. Many a home run had come to rest on the roof of the laundry over the course of the 1956 season, but the tickets disappeared into the basement, into the laundry’s furnaces.5

The famous Crosley landmark disappeared after the 1960 season when the City of Cincinnati demolished the laundry for additional parking lots. Many of the buildings surrounding Crosley Field fell to the wrecking ball in the late 1950s and early 1960s as the automobile pushed the streetcar aside as the favored mode of transportation to the ballpark.

GREG RHODES, a former chair of the Hoyt-Allen SABR Chapter of Cincinnati, is currently the Cincinnati Reds team historian. He was the founding director of the Reds Hall of Fame and Museum and served as director from 2003-2007. Two of his eight baseball books received The Sporting News-SABR Research Award (Reds in Black and White, with co-author Mark Stang, in 1999 and Redleg Journal, with co-author John Snyder, in 2001), and his book Big Red Dynasty, with co-author John Erardi, was a finalist for the 1998 Seymour Medal.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Mike Weaver, Crosley Field model builder and historian, and Chris Eckes of the Reds Hall of Fame for their contributions.

Sources

1 Greg Rhodes and John Erardi, Crosley Field: The Illustrated History of a Classic Ballpark (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 1995), 56.

2 Pat Harmon, “N.L.’s Flashy Dressers Walloped in Wardrobe,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1961: 6.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 “The End of a Dream in the Rhineland,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1956: 11.