Crosley Field: The Left Field Terrace

This article was written by Greg Rhodes

This article was published in Crosley Field essays

Babe Ruth famously stumbled on it. Outfielders regularly cursed it. Fans sat on it. And Houston Astros executive Tal Smith mimicked it.

Babe Ruth famously stumbled on it. Outfielders regularly cursed it. Fans sat on it. And Houston Astros executive Tal Smith mimicked it.

That compilation is only part of the legacy of the Crosley Field terrace, the infamous slope that extended from the left-field wall toward the infield. The terrace also extended into center and right fields, but the left-field portion was the most notorious section. Although a few other early parks had slopes (including Duffy’s Cliff in Fenway Park), none attained the iconic status of the left-field terrace at Crosley Field.

The left-field terrace extended some 30 feet from the wall, and was six feet high at the wall. This slope was a feature of the ballpark landscape in all the years the Reds played at Crosley Field (which was named Redland Field in its first 22 seasons). The center-field and right-field slopes were added in 1935, although they were not as deep or high. The slope in center field and right field extended some 10 to 12 feet from the wall, and rose about two feet. Due to its large profile, the left-field terrace was clearly visible from the stands. It often came into play and was much more difficult for outfielders to negotiate than the sections in center and right. And thus it remains the best-remembered feature of the old ballpark.

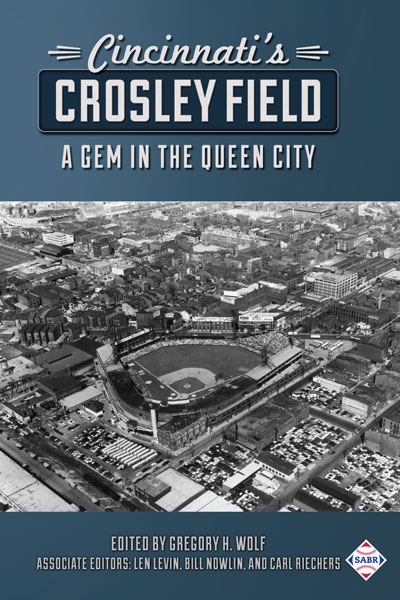

Redland Field opened in 1912 on the western edge of Cincinnati, in the floodplain of Mill Creek, an Ohio River tributary, on a plot bordered by York Street on the north, Western Avenue on the east, and Findlay Street on the south. The landscape was naturally depressed, as much as six feet below the grade of the surrounding area.

Redland Field was not the first ballpark on this site. The Reds had played there since 1884 when the club first leased the land, an abandoned brickyard, for five years at $2,500 annually.1 The club built four ballparks on this site before abandoning it in 1970 for Riverfront Stadium in downtown Cincinnati.

The earliest known photograph of the slope is from the ballpark called League Park, which opened in 1894. The photograph from August 6, 1898, shows a narrow, steep embankment up against the left-field wall. In 1902, the Reds opened a new park nicknamed “Palace of the Fans,” which, photographs show, retained this slope. The club could have eliminated the slope for new Redland Field in 1912. In fact, an architect’s rendering of the new Redland Field (on the cover of the dedication program from May 1912) shows a level playing field. But not only did club officials leave the embankment in place, they enlarged it well beyond its dimensions in the previous parks.2

It is not known why the club included the expanded terrace, but it was common practice in this era for fans to sit on the field when ballparks were oversold. Embankments helped create the effect of a natural amphitheater. The very first game the Reds played in Redland Field, Opening Day 1912, several dozen fans set on the terrace. And the vast dimensions of Redland Field also meant that few balls would ever be hit so far as to reach the terrace, except after a long roll. Left field was 360 feet from home plate and in the Deadball Era, the “hit ’em where they ain’t” era of “scientific hitting,” players did not swing for the fences. In fact, it was not until 1921 that Reds outfielder Pat Duncan hit the first home run over the left-field wall.

Two memorable events added to the terrace story in 1935. In late May, the Boston Braves, with Babe Ruth in left field, played at Crosley Field. Over the years, the story of Ruth’s surrender to the Crosley terrace has become inflated, with tales of the Babe limping off the field after suffering the humiliation of falling. While none of that seems to have happened, the bulky, 40-year-old Ruth did suffer an injury that helped precipitate his retirement. On May 28, in the final game of a three-game series, he injured his knee chasing a ball. Jack Ryder, the veteran Reds writer for the Cincinnati Enquirer, did not confirm the injury, but reported that the terrace “annoyed” Ruth and he was “slow in fielding base hits.”3 On June 2, back in Boston, Ruth announced his retirement, after a run-in with Braves owner Emil Fuchs over the injury. He said he had hurt his knee in Cincinnati chasing after a ball. “My left knee is all swelled up,” said Ruth, who wanted time off. Fuchs declined and Ruth, who had feuded with Fuchs most of the season, quit on the spot. He never played again.4

Two months after Ruth’s appearance, the Reds hosted the St. Louis Cardinals in a night game on July 31, just the sixth night game in major-league history. The lure of the defending World Series champions and a warm summer evening created overwhelming demand for tickets. The Reds oversold the ballpark, perhaps 5,000 to 10,000 over capacity with 35,000 to 40,000 in the ballpark. Much of the overflow crowd sat on the terrace in left field or up against the fence in center field and right. The crowd constantly inched forward for a better view, sometimes edging far onto the field. In the third inning, unruly fans scampered about the field, bringing a threat from the umpires of a forfeit. After the debacle, the club extended the left-field terrace into center and right fields. The Reds hoped expanding the amphitheater contour of the field would provide clearer boundaries for overflow seating, and facilitate crowd control in the future.5

The shallowness of the center- and right-field slope meant outfielders seldom had to change their fielding strategies. But the deeper and higher left-field terrace provided such a challenge that conventional positioning was ignored. Cleanup hitter or pitcher, some left fielders played them all the same. Reds Jerry Lynch and Art Shamsky both used the same strategy, standing at the base of the terrace. “I played the terrace with my body turned a bit to the left, with my left leg at the base of the hill going up,” recalled Shamsky.6 “It made practical sense to have one foot on it so my first move was either up or down.” The Dodgers’ Tommy Davis always played a few feet up the slope. “The ground comes up quickly when you’re running sideways up a hill, and a few times I ended up on my face,” he said. “So I learned to play deep and come in on balls so I wouldn’t have a problem with the rise.”7

Such tactics did not always work. Frank Robinson recalled struggling with the terrace as a young player, but finding solace in watching Willie Mays fight the terrain. “In one game against us, Willie ended up with his feet in the air and his back on the ground,” remembered Frank. “And I remember thinking, ‘OK, now I feel good, because it happened to the best.’”8

In the 1940s and 1950s, the club often used the terrace for seating on Opening Day. If ticket sales exceeded 30,000, the club placed wooden folding chairs on the terrace beginning in left field and extending into center and right as the need arose. In left field, the Reds could fit 10 to 12 rows of seats, but only three to four rows in center and right. The club stretched a rope across the front of the seats and any ball that flew or rolled into the temporary seats was a ground-rule double. Given the shallow dimensions of left field (328 feet down the line), these extra seats produced many ground-rule doubles. Jim Greengrass took full advantage on Opening Day in 1954 by hitting four balls into the temporary seats. His four doubles in one game tied the major-league record. (And led to a memorable quip after the game, when general manager Gabe Paul asked his young slugger how he was feeling after his Opening Day exploits. “Ready to negotiate,” came the quick reply.)9

The Reds ended the practice of seating fans on the field in 1959. The business manger in the 1950s, John Murdough, recalled that the cheap hits threatened to make a mockery of the game, and that the lack of facilities created problems. “There were no rest rooms, concessions couldn’t get out there,” Murdough said. “Seats were crowded so close together. Hell, if it rained you were finished. You got wet.”10

The terrace, along with the ballpark, was demolished in the early 1970s after the Reds moved to Riverfront Stadium. For years, the entrance from York Street on the north to the parking lots and businesses that now occupied the Crosley site sloped down several feet, the surviving remnant of the left-field terrace. That slope is now gone, as is Tal Smith’s tribute to the Crosley terrace in the Houston Astros ballpark. Smith, who began his front-office career in Cincinnati, always appreciated Crosley’s quirky features, and he included an incline in the new Houston ballpark, which opened in 2000. But the slope, which became known as “Tal’s Hill,” was removed after the 2016 season to shorten the distance to center field, add more seats, and eliminate a safety risk for the outfielders.

Never fear, the terrace won’t die. A full-scale re-creation of the Crosley terrace lives on in the Cincinnati suburb of Blue Ash. Some 15 miles from the original site, the Blue Ash Sports Center, which opened in 1988, features a baseball field with several Crosley elements, including the terrace.

GREG RHODES, a former chair of the Hoyt-Allen SABR Chapter of Cincinnati, is currently the Cincinnati Reds team historian. He was the founding director of the Reds Hall of Fame and Museum and served as director from 2003-2007. Two of his eight baseball books received The Sporting News-SABR Research Award (Reds in Black and White, with co-author Mark Stang, in 1999 and Redleg Journal, with co-author John Snyder, in 2001), and his book Big Red Dynasty, with co-author John Erardi, was a finalist for the 1998 Seymour Medal.

Sources

In addition to the Sources listed in the Notes, the author also consulted BaseballReference.com and Retrosheet.org.

(Thanks to Mike Weaver, Crosley Field model builder and historian, and Chris Eckes of the Reds Hall of Fame for their contributions.)

Notes

1 Greg Rhodes and John Erardi, Crosley Field: The Illustrated History of a Classic Ballpark (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 1995), 14.

2 Photographs in the uncatalogued archives of the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame.

3 Jack Ryder, “Lowly Braves Victims as Reds Chalk Up Sixth in Row,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 29, 1935: 11.

4 “‘I Quit!’ Says Babe Ruth; ‘Fired!’ Replies Braves’ Owner,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 3, 1935: 14.

5 Greg Rhodes and John Snyder, Redleg Journal: Year by Year and Day by Day With the Cincinnati Reds Since 1866 (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 2000), 267-68.

6 Lindsay Berra, “Crosley Field Terrace Had Unique Charm,” July 11, 2015, MLB.com (m.mlb.com/news/article/136100146/crosley-field-terrace-had-unique-charm/).

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 John Erardi and Greg Rhodes, Opening Day (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 2004), 243.

10 Opening Day, 26.