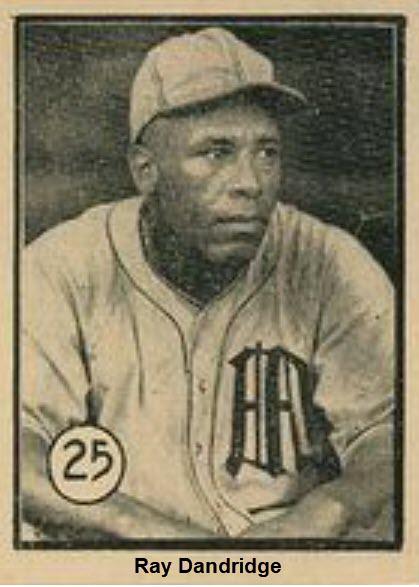

Dandy at Third: Ray Dandridge

This article was written by John Holway

This article was published in The National Pastime: Premiere Edition (1982)

Squat, bow-legged Ray Dandridge was a “vacuum cleaner” at third base, black veterans agree. Charging into bare hand a bunt, leaping to his right to backhand a line drive, racing in front of short-stop to cut off a slow roller, Ray Dandridge was “fantastic,” according to Monte Irvin, who played with Ray on the Newark Eagles. “A lot of people say Judy Johnson was best,” says Irvin, “but a lot who saw both would have to give it to Dandridge because of his hitting, his fielding, and his speed.” In fact, Dandridge forces comparison with the best third basemen of any era and any league—whites such as Pie Traynor or Brooks Robinson, or blacks such as Oliver Marcelle and Johnson.

Squat, bow-legged Ray Dandridge was a “vacuum cleaner” at third base, black veterans agree. Charging into bare hand a bunt, leaping to his right to backhand a line drive, racing in front of short-stop to cut off a slow roller, Ray Dandridge was “fantastic,” according to Monte Irvin, who played with Ray on the Newark Eagles. “A lot of people say Judy Johnson was best,” says Irvin, “but a lot who saw both would have to give it to Dandridge because of his hitting, his fielding, and his speed.” In fact, Dandridge forces comparison with the best third basemen of any era and any league—whites such as Pie Traynor or Brooks Robinson, or blacks such as Oliver Marcelle and Johnson.

Roy Campanella, who played in both the black and white leagues, calls Dandridge the best he’s ever seen at third, including his own flashy fielding teammate on the Brooklyn Dodgers, Billy Cox. And Al Lopez, who managed against Dandridge in the American Association in 1949, recalls that “Ray’s arms practically dragged the ground.” Here Lopez hunches over in an exaggerated in fielder’s crouch, knuckles swaying just above the floor. “Funny as hell, but the sonofabitch could play ball realgood. And he’d throw that ball as soon as he got it. Like Brooks Robinson.” And, adds Larry Doby, Ray’s teammate at Newark, “You couldn’t put Brooks in there with Ray in hitting.”

Ray could hit as well as field. His lifetime average was .355 in the Negro leagues, .348 in several seasons in Mexico, and .321 in the games he played against white major leaguers. Among black third basemen, only Jud Wilson hit better than that, and Wilson was a rock compared to Dandridge in the field. When black old timers voted on their all-time all black team at Ashland, Kentucky in June 1982, the result at third was a dead heat between Judy Johnson and Ray Dandridge.

Ray Dandridge’s story is even more poignant than that of most other blackball stars, because he just missed the major leagues by a year or two. He was 31 when Jackie Robinson signed with the Dodgers in 1945. Younger men made the switch with ease. Older ones had no expectations. But Dandridge was just young enough to get his hopes up, and just old enough to have them dashed.

Dandridge did get as far as the Giants’ Triple-A farm team in Minneapolis, where he watched the younger Willie Mays go on to big league stardom. Irvin, and Sal Maglie, who faced Ray in the Mexican leagues, both urged Giant manager Leo Durocher to bring Ray up in 1950, but the quota system was still in effect, and the Giants were full up-with two, Irvin and Hank Thompson. They left the 36-year old Dandridge in Minneapolis, where he was voted the league’s most valuable player. If they had brought him up to the Polo Grounds, Irvin is convinced, they could have won the 1950 pennant.

Twelve years earlier, when Ray was in his prime, New York columnist Jimmy Powers had also urged the Giants to sign him.Of course, given the times, that idea was preposterous and the Giants never even considered it. They finished third that year andwould not win a pennant until 1951. How much difference might Ray have made if he’d been in the lineup all those years along with Mel Ott, Carl Hubbell, Johnny Mize, and the other Giant stars?

Dandridge was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1913. A short, barrel-chested youth, ”built like a midget rassler,” as one player would put it, Ray was a Golden Glove boxer and football quarterback until an opposing lineman hit him with a tackle that knocked a knee out of kilter.

Ray played baseball in Virginia and North Carolina, and that’s where he first met Dave Barnhill, the diminutive fastballer who later would go up to the Minneapolis Millers with him. Barnhill remembers that Dandridge played first base with a red bandana around his neck like a railroad engineer. Ray nonchalantly scooped low throws out of the dirt, seemingly without even looking. At bat he seemed to wield a four-foot-long club, or so Barnhill thought, because no pitch was too high or too wide for him to hit.

In 1933, at the age of 19, Ray won a tryout with the Detroit Stars as an outfielder, He fancied himself a longball hitter. It was Detroit manager Candy Jim Taylor, an old third baseman, who made Ray into a shortstop and changed his hitting style completely. ‘Jim Taylor was the smartest man,” Ray says. “He took my light bat away from me. He got me out there for one solid week and learned me to hit that ball: spray here and there.” Instead of trying to pull every pitch, Dandridge learned to punch outside pitches to right field. He forgot about home runs. “Eleven home runs was tops in my entire career,” he says. “But I had a hell of an average—doubles, singles, and triples.”

“Dandridge was built close to the ground,” laughs Judy Johnson. “They would pitch up in his eyes. Right in his alley. Looked like he was chopping wood.”

A year later Dandridge was with Newark and hitting .333. There Dick Lundy, a great shortstop, transformed Ray into a third baseman. When the club’s third baseman was late reporting to spring training, Lundy told Dandridge, “Ray, you work out at third.” By the time the regular third baseman got there, Lundy told him, “You can go home now. I’ve got a third baseman.”

Ray studied hard. He admired Judy Johnson, then winding up his career with the Pittsburgh Crawfords and now a member of baseball’s Hall of Fame. But he credits Jud “Boojum” Wilson for giving him the secret that made him into a great third baseman. When a batter topped the ball, Ray says, he used to wait for the ball. The hitters consequently were beating them out. Wilson told him, “Kid, always charge a ball.” “I used to listen to oldtimers,” Ray says, “and I found out Boojum was right. You got to study the man running. If he’s a fast man, I’ve got to fire it. If he’s a slow man, I’d lob it, just get him by a step.” He was soon playing so close on bunts that “I came near to bumping the catcher.” Says former pitcher Bill Holland of the New York Black Yankees, “Dandridge had plenty of guts. Guys used to fake bunts to draw the third baseman in. Some third basemen wouldn’t come in too close. Dandridge would.”

Black veterans were soon comparing the fresh young kid with the greatest third sackers in black annals Johnson and Marcelle. Catcher Larry Brown gave Dandridge the edge. “He was a better hitter, a better fielder, and a better thrower,” Brown says. “And he was faster.” Cum Posey, owner of the Homestead Grays and perhaps the number-one authority on black baseball history, enthusiastically called Ray the nonpareil. “There never was a smoother master at third,” he wrote.

Ray was a cocky youngster. “When I came up, I was just one of those wild ones,” he says. “But I learned.” He likes to tell the story of his first meeting with the great Satchel Paige. The Eagles were in Pittsburgh for a doubleheader and won the first game. In the dressing room between games Ray got a couple of stools and stood on tip toes to look over the partition into the Craws’ dressing room. Satchel was due to pitch the second game. “All right, you’re next, you’re next, you’re next,” Ray called to Satch. “You just come out here, talkin’ ’bout how you can throw hard. We’ll see how hard you throw. We’re gonna rack you back,” and so on and so on.

On Ray’s first trip to the plate, he now admits, he did feel a little nervous and kept wondering what Satchel would throw. Boom! The first pitch exploded under his chin. Ray ducked, and he says he was a lot looser when he stood back up at the plate for pitch number two. The next pitch was another fastball, but in the strike zone and Ray lined it out for a hit. “That’s one thing I’ll say,” he says: “I don’t believe any man alive could throw that fastball by me.”

In ’35 Dandridge raised his average to .368 and appeared in the annual East-West, or all star, game, getting a single in his only at bat. He dropped to .286 in 1936, but Posey still picked the flashy fielder on his all-star team at season’s end, as he would do in the next two years as well.

In 1939 Dandridge jumped the Negro league and traveled south of the border to play with Vera Cruz in the Mexican league. The owner of the Newark Eagles, Mrs. Effa Manley, recalls: “Dandridge came to me one day with this money in his hand and said, ‘Well, Mrs. Manley, this is the money they’ve given me to come play with them. If you’ll give me the same amount, I won’t go.’ At that time we were having such a bad time financially, I decided not to give it to him. But I thought it showed a nice attitude, because he had a family to support.”

At Vera Cruz Dandridge teamed with the great shortstop Willie “Diablico” Wells, who also managed the team. “Dandridge depended on his speed and his arm,” Wells says. But he didn’t always play the hitters the way Wells, an astute field manager, thought they should be played. To complicate matters, at Vera Cruz Wells discovered that Dandridge was hard of hearing in his left ear, so he couldn’t hear Wells’ instructions to come in, play back, etc. So Wells simply transformed him into a second baseman!

At first Ray couldn’t make the pivot. He was taking the toss from short on the run and throwing across his body under his left arm to first base. As a consequence, the throws were going wild. Wells taught him to take the throw, pause, pivot, and then throw. After that, he says, “We set all kinds of records for double plays.”

We have only fragmentary statistics on Ray in Mexico. In 1943 he hit .370 and led the league in runs batted in with 70 in a roughly 90-game schedule. The next year Ray returned to Newark and led the Negro National League in runs and hits while again batting .370.

Back in Mexico in 1945 Ray managed Vera Cruz. They won the pennant by 13 games, he says. Ray himself batted .354 and set a record by hitting safely in 29 straight games. League czar Jorge Pasquel gave him a trophy inscribed in Spanish, “He came, he conquered.”

The next year Pasquel began raiding the white big leagues, waving big bucks, and signed pitchers Sal Maglie, Max Lanier, Ace Adams, and Harry Feldman, along with catcher Mickey Owens, outfielder Luis Olmo and others. Ray hit .320 that year. Box scores for five games against the white big-league pitchers show him hitting an even .400 against them. He slugged Maglie especially hard, with four hits in nine at bats. In the all-star game that summer he went 2-for-4.

In the spring of 1947 Dandridge was playing in Venezuela when the New York Yankees came through. The Yanks would win the World Series that year, and Ray played two games against then, facing Allie Reynolds, Vic Raschi, and Bill Bevens. He tripled off Bevens in the first game and scored on Phil Rizzuto’s error, as Kansas City Monarch pitcher Hilton Smith beat the Yanks 4-3.

Dandridge played in Mexico the next two summers. One of the youngsters there was Whitey Ford, and both Ford and Dandridge were named to the all-star team. Whitey was a fastball pitcher then, and Ray was a fastball hitter. He allows as how he hit Ford “pretty well.” Barnhill, who was there, is more emphatic: “He hit Whitey like he owned him!”

In 1948 we finally get complete statistics on Dandridge at Vera Cruz. He led the league in batting at .369. It was Jackie Robinson’s second year at Brooklyn, and Ray, like every other black star, saw his big opportunity coming up at last.

Ray hustled home in ’49 to manage the New York Cubans, who played their home games in the Polo Grounds, home of the New York Giants. Giant great Carl Hubbell approached Cubans’ owner Alexander Pompez, who agreed to sell his two best prospects, Barnhill and Dandridge. (Minnie Minoso wasn’t ready yet, Pompez figured.)

“Pompez called me on the road one day,” Dandridge recalls, “and asked me if I wanted to play in the big leagues before I quit. I told him, ‘Sure!’ So he said, ‘Pack up your bag and get on the plane to Minneapolis.’ Did the big chance come too late? “I was 35,” Ray grins, “but I told them I was 30.”

Dandridge and Barnhill caught the plane and hustled straight to the Millers’ stadium, suitcases and all. The game was already in progress while they suited up. Wild Mickey McDermott, a left-handed fastballer with Louisville, was opposing the Millers and had struck out about 17 or 18 men, Ray says, when the two newcomers walked into the dugout and shook hands with Minneapolis manager Tommy Heath, then took seats at the end of the bench.

“Ray, when was the last time you played?” Heath asked. “Last time I played? Are you kidding? I played yesterday.” “Well, do you think you can play today?” Heath wanted to know. “I came here to play,” Ray told him, “I didn’t come here to look around.”

“Well, how’d you like to go up and hit against him?” Heath asked, jerking his head toward McDermott.

“I’ll go up and try,” Ray shrugged. He went to the bat rack, shook several models, picked out “one to my balance,” and walked up to the plate.

The first pitch whistled in under Dandridge’s chin. But he was used to those and on the next pitch shot a line drive toward right field, which the second baseman leaped and grabbed. And that, Ray remembers, was his debut in Organized Ball.

Barnhill started and won the second game, and Ray made some good plays in the field. After that, Barnhill says, when the players took their seats, the dugout was integrated, there were no more blacks on one end, whites on the other. “They treated me and Ray like we were on the ball club,” Barnhill says. “Well, we were on the club. It wasn’t who was white or who was black. Oh man, I had some experiences with that ball club-good experiences.”

Traveling was no problem, Barnhill says. The two blacks stayed in white hotels with the team everywhere but Louisville and Kansas City.

Heath installed Dandridge at second base. When the Giants sent second baseman Davey Williams down to Minneapolis for more seasoning, Dandridge was hitting like a terror. Heath asked him to move to the outfield. “I don’t want to play no damn outfield,” Dandridge retorted, so Heath shrugged and decided he had no choice but to keep Williams on the bench.

When the Millers’ third baseman got spiked, Heath asked Dandridge, “Ray, ever play third before?”

“I’ll go over there and try,” Ray said modestly.

On the first pitch the batter dragged a bunt to third. Ray swooped in, and in one fluid motion threw the man out. The Millers watched in awe. Barnhill simply winked. “You just threw the rabbit in the briar patch,” he told Heath.

That year Ray played first base, second base, shortstop, and third, hit .369, and just missed winning the batting championship. He was voted Rookie of the Year-at the age of 35.

Why didn’t the Giants bring Ray up to the parent club that year? It was Leo Durocher’s first full season with

the team, and he complained that he had inherited a muscle-bound team of sluggers who couldn’t run. Sid Gordon on third hit 26 home runs but was slow afield and afoot.

The Giants made their first tentative experiment in race relations that year, bringing Monte Irvin, Ray’s old

teammate at Newark, up to play a few games at outfield and third base; Monte hit .224. Twenty-three-year

old Hank Thompson, a product of the Kansas City Monarchs, played second for half the season and hit .280. The Giants finished fifth, 24 games behind the Dodgers, and Leo swore he would rebuild the team in his own

aggressive image in 1950. Would he cast his eyes toward Minneapolis and Dandridge?

No. Instead, Leo brought Eddie Stanky over from Brooklyn to play second and shifted Thompson to third. Ray would have to stay in Minneapolis in 1950. He had another splendid year there, hitting at a .311 clip and knocking out a personal-high 11 round-trippers. When the votes for league Most Valuable Player were counted, Ray Dandridge came out on top.

The Giants meanwhile were making a dash for the pennant, in hot pursuit of the Phillies and Dodgers.

Sal Maglie, who had seen Ray in Mexico, pleaded with the Giants’ top scout to bring him up.

“But he’s too old,” Maglie was told.

”That’s not the question,” Sal replied. “We have a month to play. Bring him up for a month.”

Looking back today, Maglie shakes his head. The scout didn’t have the authority, he says; it was up to Giants’ owner Horace Stoneham. “But we could have won the pennant. I know damn well, with Dandridge playing third, we’d have won that pennant in ’50.”

In the Giants’ defense, it must be said that it made sense to go with youth. Thompson was having a good year, hitting .289 with 91 RBIs. In fact, it is hard to see where Ray could have fit into the team, with Stanky

hitting .300 at second and AI Dark, a .279 hitter, at short. The weak spot of the infield was first baseman Tookie Gilbert, who batted only .220. Could Dandridge have handled that position? At least he could have provided back-up insurance at the other three positions, and he could have given Durocher a tenth bat in emergencies.

Irvin blames the quota system, still in effect on those few teams that had integrated. Then, too, the Millers

won the American Association flag that year. “They were going to call me and Ray to finish the season with the Giants,” Barnhill says, “but we had to play in the playoffs instead. I could have had a cup of coffee and a

cookie in the big leagues. You never saw a man as mad as I was! Man, was I mad!”

The next year, the fateful ’51 season, the Giants had high hopes but began miserably. Thompson, a moody, unpopular man, was not doing the job at third. Meanwhile, the Giants had sent a kid outfielder to Minneapolis from their Trenton farm club, a youngster by the name of Willie Mays. “Did you know I was part of the cause of Willie going to the Giants?” Dandridge asks. He had seen Mays, then 19, play in Cuba one winter, and a few days later, as Ray knelt in the on-deck circle, a spectator caught his eye. “Damn,” he said to himself, “that looks like Rosy Ryan sitting there.” Ryan was Minneapolis general manager, and as Ray trotted back to the dugout after his at bat, he stopped at Ryan’s box. “What are you doing here, Rosy?” he asked.

“I came to look at a ballplayer,” Ryan replied. “What do you think of this boy Mays? How do you think he’d do at Minneapolis?”

Ray said, “Are you kidding? If you came here to get him, then get him!”

When Mays reported to Minneapolis, he hit right ahead of Dandridge in the batting order. “Every time Willie came up and hit one over the center-field fence, it seemed like I came up and hit one over the left-field fence,” Dandridge grins. Pretty soon, every time Willie hit a homer, Ray would hit the dirt as the pitcher aimed the next one at his head. Ruefully he dusted himself off and told manager Heath, “You better get that man out from in front of me or you’re going to get [me] killed!”

Willie recalls, “Ray Dandridge was like my father.” Once, Mays says, a pitcher named Jim Atkins with Louisville threw three straight beanballs at the 20-year-old outfielder. While Willie lay sprawled on the ground, he looked up to see Dandridge advancing on Atkins. Atkins was huge, about 6’4″ or 6’5″, Willie says. Dandridge was about 5’7″. “Now I’m on the ground, I’m looking up, and I’m looking at Ray saying something to Atkins, and I’m saying to myself, ‘My God, don’t let this guy hit Ray.’ “

Back in the dugout Mays asked Dandridge what he had said. Ray replied: “I told the guy, ‘Back home I have two dogs. I have a dog that will go right to your spot if I say Bite! Then I got another one that just sits back until the first one gets through, and then I will say Bite! again.’ “

Atkins told Ray, “Well, Ray, I like you, but I don’t like that little black worm over there.”

And Ray replied, “You call him that again and I’ll sic my third dog on you!”

One spring day in 1951, before an exhibition game at Sioux City, Iowa, Willie and Ray were sitting in a movie when a message flashed on the screen: “Willie Mays, report to the box office.” In a moment Mays returned and whispered, “Ray, I’ve got to go to the hotel.” Ray stayed for the end of the show, then joined his teammates.

“Hey, Skip, where the hell is Willie at?” he asked Heath.

“Didn’t you know?” Heath replied. “He’s already on a plane. He’s halfway to New York now.”

Dandridge went back to the room, gathered Mays’ belongings and mailed them to the Polo Grounds.

But again there was no plane ticket for Ray, although he hit .324. In fact, the Giants had to dismiss second baseman Artie Wilson, ironically Mays’ old tutor with the Birmingham Black Barons, to maintain the quota when Willie joined the team.

Instead of calling up Dandridge, Durocher moved outfielder Bobby Thomson to third. Though Thomson was no Dandridge with the glove, he hit with power, and the rest is history. But it’s fascinating to speculate how history might have been changed if the Giants had put Ray on third. Would he have meant an extra victory or two? If so, there would not have been a playoff and Thomson would not have hit his “shot heard ’round the world.”

In 1952 Ray hit .292 at Minneapolis with ten home runs. Judy Johnson, scouting for the Phillies, urged them to buy Ray, but the Giants wouldn’t sell. They wouldn’t bring him up to the Polo Grounds either. Davey Williams, a journeyman second baseman, had replaced Stanky but hit only .254. Irvin broke his ankle, Mays was drafted, Hank Thompson was moved to the outfield, and Bobby Thomson continued to struggle with the unfamiliar hot corner. The Giants finished second, four and a half games behind the champion Brooklyn Dodgers.

Finally, in 1953, the Giants let Ray go, to Oakland in the Pacific Coast League. But Ray, by then 40 years old, ran into the catcher chasing a foul ball, hurt his elbow, hit only .268, and at the end of the year was given his release.

He was out of the game in 1954, but the arm came around in ’55 and he played with Bismarck, North Dakota, where he hit .360. But he was 42 years old. At last he realized that the big-league doors would never open for him. He called it a career.

Dandridge returned to Newark, tending bar and scouting part-time for the Giants.

“I met Horace Stoneham, the Giants’ owner, at an oldtimers’ game,” Ray says. “I cussed him out. My ambition was to go from the lowest to the highest. They could have called me up. I asked him, ‘Gee, couldn’t you at least have brought me up even for one week, just so I could say I’ve actually put my foot in a major-league park?’”

JOHN B. HOLWAY is the author of Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues.