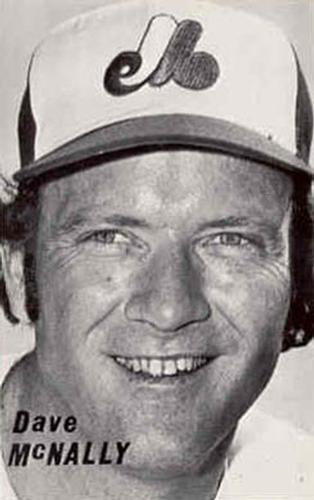

Dave McNally and Peter Seitz at the Intersection of Baseball Labor History

This article was written by Ed Edmonds

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

On September 26, 1962, Dave McNally took the mound for the first time as a Baltimore Orioles starter in game one of a doubleheader at Memorial Stadium. The lefty, who spent most of the year pitching for the Elmira Pioneers, hurled the first of his 33 career shutouts. McNally’s two-hit, three-walk effort produced the first of his 184 career wins.

On September 26, 1962, Dave McNally took the mound for the first time as a Baltimore Orioles starter in game one of a doubleheader at Memorial Stadium. The lefty, who spent most of the year pitching for the Elmira Pioneers, hurled the first of his 33 career shutouts. McNally’s two-hit, three-walk effort produced the first of his 184 career wins.

McNally undoubtedly did not realize that evening that he would personally be at the forefront of a baseball labor movement over the next thirteen years that would radically change baseball’s reserve system and salary structure. During those years, McNally would first battle with Orioles general managers Harry Dalton and Frank Cashen over his annual salary; second, agree in 1974 to be one of 29 players who were the first to use a union-negotiated system of salary arbitration hearings; third, demand a trade after the 1974 season for a needed “change of scenery” and not sign a contract with his new team; and, fourth, with fellow pitcher Andy Messersmith, force an arbitration panel decision over the reach of the reserve system.1

The arbitrator in McNally’s 1974 salary arbitration in New York City was, like the pitcher, a veteran at his craft. Peter Seitz’s labor resume was impressive. He served in the mid-1960s as a member of the American Arbitration Association’s labor-management panel that analyzed New York City’s collective-bargaining procedures. The panel’s recommendations established the city’s Office of Collective Bargaining and produced a foundational labor law scheme. Seitz also served on the National Wage Stabilization Board, as counsel and assistant to the director of the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, and director of industrial relations for the Defense Department.2

By 1974, Seitz was already the principal arbitrator for disputes between the National Basketball Association and the National Basketball Players Association.3 He would succeed Gabriel Alexander that year as the third permanent arbitrator for major league baseball and the Major League Baseball Players Association.4 Seitz delivered a major decision in an arbitration grievance that declared Jim Hunter a free agent because of a breach of contract by Oakland Athletics owner Charles Finley.5

McNally probably knew little about Peter Seitz when he decided the hurler’s salary dispute with the Orioles in McNally’s favor. Although McNally was a critical backup plan behind the December 1975 grievance in front of John Gaherin, Marvin Miller, and Seitz, McNally was back home in Billings, Montana, and never appeared before the panel.6 However, Dave McNally and Peter Seitz are forever linked in baseball’s critical decision that altered the reserve system and established the foundation for baseball’s free agency system.

This article will focus on McNally’s labor conflicts with Orioles management and his salary arbitration hearing. Although much has been written about Seitz’s McNally-Messersmith decision, Dave McNally rarely discussed it. The article will finish with a few of McNally’s reported comments on that decision.

Salary Disputes 1969–73

After McNally’s single game appearance in 1962, the left-hander joined a starting staff the following year that included future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts and veterans Milt Pappas and Steve Barber. By 1965, McNally had moved from the fifth starter to the middle of the rotation and pushed his salary from $12,000 to $17,000.7 The following year, he was at the top of the rotation and won the decisive fourth game in the World Series sweep over the Los Angeles Dodgers. The effort pushed McNally’s salary to $24,000. When Baltimore dropped to a sixth-place finish in 1967 — in part due to McNally’s sore elbow as well as injuries to Barber, Wally Bunker, and Jim Palmer — Dalton initially reduced McNally’s salary by $4,000 with a stipulation that it would return to the same $24,000 as the previous year if the pitcher was on the Active List for the first thirty days of the season.8 Dalton’s decision would establish an atmosphere of conflict between McNally and the front office for the remainder of the pitcher’s Oriole career.

McNally had a breakout 1968 season when he posted the first of his four consecutive 20-win seasons by winning 22 of 32 decisions with a 1.95 ERA and a fifth-place finish in the MVP voting. However, baseball’s offseason was highlighted by labor strife and it impacted McNally’s salary negotiations. Baltimore Sun writer Lou Hatter wrote that “McNally and [Tom] Phoebus, especially the former, will remain Baltimore-based holdouts for two reasons. Not only are both upholding the Players Association posture against the owners; neither has been satisfied by three 1969 salary offers from Oriole personnel director Harry Dalton.”9

McNally asserted that “‘the owners’ arbitration refusal is a good point in our favor as far as outside people are concerned. I think they (the owners) must be afraid of something.’”10 McNally did not sign his new deal until February 28, holding out for nine days. McNally was described by Sun writer Jim Elliot as “extremely satisfied” with his resulting salary increase to $51,000.11

McNally’s negotiations with Dalton were even more protracted in 1970, when McNally missed two and one-half weeks in a holdout resolved on March 5 when he signed for $65,000.12 The pitcher remarked after signing the new deal that he “didn’t come to Florida to become a holdout. … Considering my performance the last two years, I proposed what I considered to be a fair figure. I was trying to sign. [Orioles management] were being difficult about it.”13

The 1971 Orioles lost the World Series in seven games to the Pittsburgh Pirates, but McNally won 21 of his 26 regular season decisions, and he was joined by Mike Cuellar, Pat Dobson, and Jim Palmer as 20-game winners. McNally managed to wrangle a $20,000 raise for the season by signing on February 24 after missing one week of spring training. Jim Elliot reported that McNally was “‘very close’ to the $100,000 he was seeking,” but, in reality, he was well short of the mark. The writer reported that a smiling McNally noted that “I’m not supposed to give out any figures, but I got very close to what I wanted.”14

After posting his fourth straight 20-win season in 1971, McNally finally broke through the $100,000 barrier, but it did not come without the usual struggle with the front office. In becoming the first American League pitcher to exceed the magical figure, McNally and his agent waited until February 27 to finally work out a $20,000 raise over his 1971 salary.15 A few days after signing the deal, McNally argued. “It sounds funny for me to say this, but I don’t think I should have to fight to have gotten what I did. Look at it this way: My record the past four years was better than Seaver’s and Jenkins’, wasn’t it?”16 McNally was referencing his understanding that Tom Seaver and Ferguson Jenkins were two of the four National League pitchers making over $100,000. Bob Gibson and Juan Marichal were also supposedly above the $100,000 mark.17

The 1972 Orioles dropped to 80-74, and McNally posted the fewest wins of the Birds top four starters despite a solid 2.95 ERA. McNally missed only the beginning of Orioles spring training before signing for the same $105,000 for 1973.18 McNally posted a 17-17 record in 1973, but, again, McNally was not pleased with management’s contract offer of the same $105,000 for the 1974 season, so he decided to join the first class of players to use the recently negotiated salary arbitration process to determine his compensation for the upcoming season. Years later manager Earl Weaver reflected on McNally stating that the pitcher was “a great competitor, a gentleman…I will say this, though, when it came down to contract dealings, he was mercenary. He was as tough as any player I have ever seen. Every spring, [general manager] Harry Dalton would start out with a dollar offer, and McNally would stay away [from camp] until Dalton got all the way up to the figure Dave wanted. It was simple, really. Unless he got what he wanted, he would not play.”19

The Salary Arbitration Hearing

McNally and agent Ed Keating joined with Cleveland attorney Bill Carpenter of International Management Company to fashion their arbitration case. After a hearing in New York, Peter Seitz ruled in their favor.20 Seitz heard five cases in the initial year of salary arbitration, the most of any arbitrator.21 He also found in favor of Bill Sudakis while ruling against Paul Blair, Tim Foli, and Gene Michael.22

McNally’s arbitration hearing was held on Thursday, February 21, 1974, in a New York City hotel.23 Prior to the hearing, McNally presented his thoughts to Sun reporter Cameron Snyder. After recounting his earlier disputes with management over salary offers, “you can go back [to previous years of negotiations] where you thought you were not treated right and that also has to be considered by the arbitrator. We think we have a good case.”24 McNally researched his 1973 pitching record and Bill Carpenter “put them together in written form.”25 Sun writer Ken Nigro observed that the pair “obviously based their case mostly on the fact the Birds were shut out six times while McNally was on the mound. They lost three of the games by 1-0 scores, two by 2-0 and another by 3-0.”26 A split of those six starts would have improved McNally’s record from 17-17 to 20-14, a fifth 20-win season. Although McNally felt that it was a “helluva experience” where “I learned a lot,” he felt that Frank Cashen breached some confidences noting that “I don’t mind Frank…saying anything about my ability or his personal opinion of me. …He is entitled to that. But there were some things said during the hearing that I don’t think should have been said. That’s all I want to say about it.”27 He was obviously pleased with Seitz’s favorable decision because “we were $10,000 apart… And if it wasn’t for arbitration, we probably still would have been $10,000 apart when I finally signed.”28

The hearing lasted three and one-half hours, “from 10 a.m. until about 1:40 p.m.”29 As McNally told the Sun’s Nigro:

We presented our case then they presented theirs. After that both sides add any additional information. The arbitrator asked very few questions. In fact, I would say he was 90 per cent a listener. He seemed to know about baseball, but it was tough to tell what he was listening to and what he wasn’t. . . . It was much more formal than I thought it would be. . . . I had talked to Dick Moss [counsel for the Players’ Association] and he told me it would be a very informal hearing with a relaxed atmosphere. But it was more like a regular court trial. . . . Was I nervous? I sure was.30

The length of the hearing was “because everything was detailed.”31 Cashen came well prepared for the hearing, and presented a written summation with 22 points supporting their position.32

Peter Seitz was also the arbitrator for teammate Paul Blair, who felt that it was unfortunate that they shared the same decision maker, saying, “The one thing I didn’t like was that the same arbitrator heard my case and Dave’s and I don’t think that helped.”33

Marvin Miller on 1974 Salary Arbitration

Marvin Miller generally felt comfortable about the arbitration decisions, but one aspect bothered him about the decision-making process of the arbitrators. “It might be unfair for me to say this…but I was struck by the general inclination of the arbitrators to split their cases. Maybe it was pure coincidence. I don’t know,” he told Jerome Holtzman of The Sporting News. According to Miller, every arbitrator who presided at two hearings split his decision, 1-1. Those who had three cases voted 2-1 and the one who heard five voted 3-2. There was only one exception. One arbitrator heard four cases, all involving Oakland players, and voted 3-1 in favor of the players.34

Peter Seitz on Arbitration

Peter Seitz, in reflecting on what he preferred to call “High-Low Arbitration,” wrote a short piece for The Arbitration Journal with the hope “that the desperate thirst for information may be slaked by a few observations of a participant.”35 Claiming that “the writer can testify only as to the five hearings at which he presided,” Seitz argued that “it seemed to him that the clubs, on the whole (with exceptions), were better prepared and made a more professional presentation than the players.”36 Pushing his observations further, Seitz stated that “the hearings were noteworthy in the respect that the hearings at which I presided were inundated by a torrent of statistical data.”37 Seitz next presented a hypothetical illustration with an explicit statement in a footnote that it should not be taken as an actual example of one of the presentation that he heard. However, his example did track closely the facts in the McNally case: “For example; if a club asserts that in the past year, the earned run average of batters against a pitcher increased significantly and his win-lose figure was less impressive than in previous years. Accordingly, no increase in pay was offered by the club. The pitcher, however, argues, with a wealth of figures, that in the games he lost, the margin of defeat was mostly by one or two runs; and in most of those games, his team hit well below its season’s batting average.”38 McNally’s hearing was the only one of Seitz’s five to involve a pitcher, and McNally’s primary arguments were close decisions and weak offensive support. Furthermore, McNally’s 1973 salary of $105,000 matched the Orioles offer.

McNally-Messersmith Arbitration

After the 1974 season, McNally requested a trade, and he was sent to Montreal.39 When negotiations with the Expos broke down, Montreal renewed McNally’s salary for the 1975 season with a small increase. McNally played part of the season without signing that deal, and he agreed to remain unsigned after retiring on June 9. McNally agreed to join Andy Messersmith on the historic grievance that determined that both players were now free agents and no longer bound by the reserve system. Later in the year the Expos tried to negotiate a deal, but McNally, despite no future plans to return to the game, refused to sign. “To this day, I have tremendous respect for Dave,” says Wally Bunker, “because he turned down significant money in his pocket for a cause that helped a lot of other future players.”40

After the 1974 season, McNally requested a trade, and he was sent to Montreal.39 When negotiations with the Expos broke down, Montreal renewed McNally’s salary for the 1975 season with a small increase. McNally played part of the season without signing that deal, and he agreed to remain unsigned after retiring on June 9. McNally agreed to join Andy Messersmith on the historic grievance that determined that both players were now free agents and no longer bound by the reserve system. Later in the year the Expos tried to negotiate a deal, but McNally, despite no future plans to return to the game, refused to sign. “To this day, I have tremendous respect for Dave,” says Wally Bunker, “because he turned down significant money in his pocket for a cause that helped a lot of other future players.”40

Peter Seitz once again was pivotal as the lead arbitrator on the three-person panel including Marvin Miller and John Gaherin. Much has been written about the historically important McNally-Messersmith decision and Seitz’s written opinion. However, McNally rarely spoke about it. In a 1986 article by John Eisenberg, he noted that “eleven years later, McNally does not consider himself a revolutionary.” McNally argued, “I do not look back at [the case] with pride, or anything like that. … Maybe I would feel differently about it if I had testified. But I did not. I never left Billings. The only part I played was a name on a suit. My name was involved. But not me.”41

ED EDMONDS is Professor Emeritus of Law at the Notre Dame Law School. He is the former law library director at William & Mary, Loyola New Orleans, St. Thomas (Minnesota), and Notre Dame. With Frank Houdek, he is co-author of “Baseball Meets the Law” (McFarland 2017). He taught sports law for 35 years, and he has published law review articles on labor and antitrust issues involving baseball and salary arbitration.

Notes

1 Ian MacDonald, “Expos’ Trade For Fryman May Be Calm Before Storm,” Montreal Gazette, December 5, 1974.

2 For the assertion that Peter Seitz was the arbitrator, the author relies primarily on a document listing all arbitrators from 1974 through 2008. Salary Arbitration Results by Season, 1998-2008, MLBPA and STATS, Inc., 22. The information that Seitz heard McNally’s case was verified via telephone call on February 28, 2020. The information on Seitz’s labor background was taken from Damon Stetson, “Peter Seitz, 78, The Arbitrator in Baseball Free-Agent Case,” The New York Times, October 19, 1983.

3 Stetson, “Peter Seitz.”

4 Robert F. Burk, More Than a Game: Players, Owners, & American Baseball Since 1921 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 197; Charles Korr provides some commentary on MLBPA’s Dick Moss offering Peter Seitz the position as permanent arbitrator. Charles P. Korr, The End of Baseball As We Knew It: The Players Union, 1961-81 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 141-42. Alexander’s resignation is discussed by Marvin Miller in his autobiography. Marvin Miller, A Whole Different Ball Game: The Sport and Business of Baseball (New York, Carol Publishing Group, 1991), 246.

5 Jerome Holtzman provided a detailed discussion of the Hunter decision in the Official Baseball Guide. Jerome Holtzman, Official Baseball Guide for 1975 284-300 (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1975), 284-300; Korr, The End of Baseball, 142-46.

6 John Eisenberg, “McNally Shook Baseball’s Foundation, But He Has Solid One Now in Montana,” Baltimore Sun, July 17, 1986.

7 The salary information in this article is based upon McNally’s contract card held by the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

8 McNally’s contract card.

9 Lou Hatter, “Four Orioles Prepare to Sit Tight,” Baltimore Sun, February 19, 1969.

10 Hatter, “Four Orioles.”

11 Jim Elliot, “Powell and Phoebus Remain Bird Holdouts,” Baltimore Sun, March 1, 1969.

12 McNally’s contract card. The figure was also reported “as an estimated $65,000 contract, after setting an $80,000 price which would have doubled his 1969 income.” Lou Hatter, “Dave McNally’s Late Start Puts Guess In His Condition,” Baltimore Sun, March 19, 1970.

13 Lou Hatter, “Dave McNally’s Late Start;“Dave McNally Inks Early Bird Contract,” Casper Star Tribune, February 26, 1974.

14 Jim Elliot, “McNally, Cuellar In Line,” Baltimore Sun, February 25, 1971.

15 Edwin Pope, “$100,000-a-Year Club Now Includes 23 Major Leaguers,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1972 (McNally “was the first American League pitcher to receive a contract worth $100,000 when he signed with the Orioles prior to the 1972 season.”)

16 Milton Richman, “Big Money O’s,” Tampa Times, March 4, 1972.

17 Richman, “Big Money O’s.”

18 McNally’s Contract Card. Elliot lists Denny McLain as the first $100,000 American League pitcher based on the final year of his three-year contract. Baseball-Reference.com has a note to such effect by his 1971 Washington Senators salary entry, but does not list him at $100,000 in any main column. Jim Elliot, “McNally Signs, Looks for Comeback Season,” Baltimore Sun, March 5, 1973.

19 John Eisenberg, “McNally Shook Baseball’s Foundation, But He has Solid One Now in Montana,”Baltimore Sun, July 17, 1986.

20 Gary Long, “O’s McNally Already 1-0 In $ League,” Miami Herald, Feb. 27, 1974 (“Peter Sykes (sic) of the American Arbitration Association apparently believed him.”); Ken Nigro, McNally Is Bitter Despite Salary Win, Baltimore Sun, February 27, 1974; Cameron C. Snyder, “3 Oriole Stars Take Salaries to Arbitration,” Baltimore Sun, February 12, 1974.

21 “Salary Arbitration Results by Season.”

22 “Salary Arbitration Results by Season.”

23 Snyder, “3 Oriole Stars.”

24 Snyder, “3 Oriole Stars.”

25 Nigro, “McNally Is Bitter.”

26 Nigro, “McNally Is Bitter.”

27 Nigro, “McNally Is Bitter.”

28 Nigro, “McNally Is Bitter.”

29 Nigro, “McNally Is Bitter.”

30 Nigro, “McNally Is Bitter.”

31 Long, “O’s McNally Already 1-0.”

32 Nigro, “McNally Is Bitter.”

33 Nigro, “McNally Is Bitter.”

34 Jerome Holtzman, “Arbitration a Success, Players and Owners Agree,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1974, 53.

35 Peter Seitz, “Footnotes to Baseball Salary Arbitration,” The Arbitration Journal (1974) 29: 98.

36 Seitz, “Footnotes,” 99.

37 Seitz, “Footnotes,” 100.

38 Seitz, “Footnotes,” 100.

39 MacDonald, “Expos’ Trade For Fryman.”

40 Eisenberg, “McNally Shook Baseball’s Foundation.”

41 Eisenberg, “McNally Shook Baseball’s Foundation.”